1960s: Erikson

Jennifer Paris; Antoinette Ricardo; Dawn Rymond; Lumen Learning; and Diana Lang

Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

Erik Erikson suggested that our relationships and society’s expectations motivate much of our behavior in his theory of psychosocial development. Unlike Freud, Erikson believed that we are not driven by unconscious urges. He is considered the father of developmental psychology because his model gives us a guideline for the entire life span and suggests certain primary psychological and social concerns throughout life.[1]

Erikson expanded on Freud’s theory by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations. He also added three stages of social and emotional domains regarding adult development. He believed that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life and that the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than the id does.[2] We make conscious choices in life and these choices focus on meeting certain social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can make a contribution to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial issues.

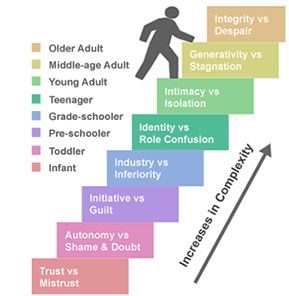

Erikson divided the lifespan into eight stages. In each stage, we have a major psychosocial task to accomplish or crisis to overcome. Successful completion of each developmental task results in a sense of competence and a healthy personality. Failure to master these tasks leads to feelings of inadequacy. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespan as we face these challenges in living.[3]

These eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the life span. However, these stages or crises can occur more than once and can occur at different ages.[4] For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is a prerequisite for the next development crisis.[5] His theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in some cultures, but not in others. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices. Here is a brief overview of the eight stages[6]:

| Name of Stage and Age | Description of Stage |

| Trust vs. mistrust (0-1 year) | The infant must have basic needs met in a consistent way in order to feel that the world is a trustworthy place. |

| Autonomy vs. shame and doubt (1-2 years) | Mobile toddlers have newfound freedom that they like to exercise and by being allowed to do so, they learn some basic independence. |

| Initiative vs. guilt (3-5 years) | Preschoolers like to initiate activities and emphasize doing things “all by myself.” |

| Industry vs. inferiority (6-11 years) | School-aged children focus on accomplishments and begin making comparisons between themselves and their classmates. |

| Identity vs. role confusion (adolescence) | Teenagers try to gain a sense of identity as they experiment with various roles, beliefs, and ideas. |

| Intimacy vs. isolation (young adulthood) | In our 20s and 30s, we make some of our first long-term commitments in intimate relationships. |

| Generativity vs. stagnation (middle adulthood) | In the 40s through the early 60s we focus on being productive at work and home and are motivated by wanting to feel that we’ve made a contribution to society. |

| Integrity vs. Despair (late adulthood) | We look back on our lives and hope to like what we see — that we have lived well and have a sense of integrity because we lived according to our beliefs. |

Trust vs. Mistrust

From birth to 12 months of age, infants must learn that adults can be trusted. This occurs when adults meet a child’s basic needs for survival. Infants are dependent upon their caregivers, so caregivers who are consistently and appropriately responsive and sensitive to their infant’s needs help their baby to develop a sense of trust; their baby will see the world as a safe, predictable place. Unresponsive or inconsistent caregivers who do not meet their baby’s needs can elicit feelings of anxiety, fear, and mistrust; their baby may see the world as unpredictable and unsafe. If infants are treated cruelly or their needs are not met appropriately, they will likely grow up with a sense of mistrust for people in the world.

Autonomy vs. Shame/Doubt

As toddlers (ages 1–3 years) begin to explore their world, they learn that they can control their actions and act on their environment to get results. They begin to show clear preferences for certain elements of the environment, such as food, toys, and clothing. A toddler’s main task is to resolve the issue of autonomy vs. shame and doubt by working to establish independence. This is the “me do it” stage. For example, we might observe a budding sense of autonomy in a 2-year-old child who wants to choose her clothes and dress herself. Although her outfits might not be appropriate for the situation, her input in such basic decisions has an effect on her sense of independence. If denied the opportunity to act on her environment (within developmentally-appropriate measures), she may begin to doubt her abilities, which could lead to low self-esteem and feelings of shame.

Initiative vs. Guilt

Once children reach the preschool stage (ages 3–6 years), they are typically capable of initiating activities and asserting control over their world through social interactions and play. According to Erikson, preschool children must resolve the task of initiative vs. guilt. By learning to plan and achieve goals while interacting with others, preschool children can master this task. Initiative, a sense of ambition and responsibility, occurs when parents allow a child to explore within limits and then support the child’s choice. These children tend to develop self-confidence and feel a sense of purpose. Those who are unsuccessful at this stage—with their initiative stifled by over-controlling caregivers—may develop feelings of guilt.

Industry vs. Inferiority

During the elementary school stage (ages 6–12 years), children face the task of industry vs. inferiority. Many children begin to compare themselves to their peers to see how they measure up. They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they feel inferior and inadequate because they feel that they don’t measure up. If children do not learn to get along with others or have negative experiences at home or with peers, an inferiority complex might develop into adolescence and adulthood.

Identity vs. Role Confusion

In adolescence (ages 12–18 years), children face the task of identity vs. role confusion. According to Erikson, an adolescent’s main task is developing a sense of self. Adolescents struggle with questions such as “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Along the way, most adolescents try on many different “selves” or identities to see which ones fit; they explore various roles and ideas, set goals, and attempt to discover their “adult” selves.

Adolescents who are successful at this stage have a strong sense of identity and are able to remain true to their beliefs and values in the face of problems and other people’s perspectives. When adolescents are apathetic, do not make a conscious search for identity, or are pressured to conform to their caregivers’ ideas for the future, they may develop a weak sense of self and experience role confusion. They may be unsure of their identity and confused about the future. Teenagers who have difficulty adopting a positive role may struggle to “find” themselves as adults.

Intimacy vs. Isolation

People in early adulthood (20s through early 40s) are concerned with intimacy vs. isolation. After we have developed a sense of self in adolescence, many of us are ready to share our life with others. However, if the previous developmental stages have not been successfully resolved, young adults may have trouble creating and maintaining healthy relationships with others. Erikson said that we must have a strong sense of self before we can form strong, successful intimate relationships. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.

Generativity vs. Stagnation

When people reach their 40s, they enter the time known as middle adulthood, which extends to the mid-60s. The social task of middle adulthood is generativity vs. stagnation. Generativity involves finding your “life’s work” and fostering the development of others through activities such as volunteering, mentoring, and rearing children. During this stage, middle-aged adults begin contributing to the next generation, often through childbirth and caring for others; they also engage in meaningful and productive work which positively benefits society. Those who do not master this task may experience stagnation and feel as though they are not leaving a mark on the world in a meaningful way; they may have little connection with others and little interest in productivity and self-improvement.

Integrity vs. Despair

From the mid-60s to the end of life, we are in a period of development known as late adulthood. Erikson’s task at this stage is called integrity vs. despair. He said that people in late adulthood reflect on their lives and feel either a sense of satisfaction or a sense of failure. People who feel proud of their accomplishments feel a sense of integrity, and they look back on their lives with few regrets. However, people who are not successful at this stage may feel as if their life has been wasted. They focus on what “would have,” “should have,” and “could have” been. They may face the end of their lives with feelings of bitterness, depression, and despair.

Key Takeaways

Erikson was a student of Freud but focused on conscious thought.

- His stages of psychosocial development address the entire lifespan and suggest a primary psychosocial crisis in some cultures that adults can use to understand how to support children’s social and emotional development.

- Certain cultures may need to resolve the stages in different ways based upon their cultural and survival needs.

- During each of Erikson’s eight development stages, two conflicting ideas must be resolved successfully in order for a person to become a confident, contributing member of society. Failure to master these tasks leads to feelings of inadequacy.

- The stages include: trust vs. mistrust, autonomy vs. shame and doubt, initiative vs. guilt, industry vs. inferiority, identity vs. role confusion, intimacy vs. isolation, generativity vs. stagnation, and integrity vs. despair.

- This chapter is an adaptation of Child Growth and Development by Paris, Ricardo, and Rymond, used under a CC BY 4.0 license. ↵

- Erikson, E. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. International Universities Press. ↵

- Erikson, E. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. International Universities Press. ↵

- Erikson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W.W. Norton & Company. ↵

- Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In J. Adelson, (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 159-187). John Wiley & Sons. ↵

- Erikson's Eight Stages is adapted from Lumen Learning's 8 Stages of Psychosocial Development, used under a CC BY SA license. ↵