Early Childhood

Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; and Diana Lang

Our discussion will now focus on the physical, cognitive, and socioemotional development during the ages from two to six, referred to as early childhood. Early childhood represents a time period of continued rapid growth, especially in the areas of language and cognitive development. Those in early childhood have more control over their emotions and begin to pursue a variety of activities that reflect their personal interests. Parents continue to be very important in the child’s development, but now teachers and peers exert an influence not seen with infants and toddlers.[1]

Children between the ages of two and six years tend to grow about 3 inches in height and gain about 4 to 5 pounds in weight each year. Just as in infancy, growth occurs in spurts rather than continually. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000) the average 2-year-old weighs between 23 and 28 pounds and stands between 33 and 35 inches tall. The average 6-year-old weighs between 40 and 50 pounds and is about 44 to 47 inches in height. The 3-year-old is still very similar to a toddler with a large head, large stomach, and short arms and legs. By the time the child reaches age 6, however, the torso has lengthened and body proportions have become more like those of adults.

This growth rate is slower than that of infancy and is accompanied by a reduced appetite between the ages of 2 and 6. This change can sometimes be surprising to parents and lead to the development of poor eating habits. However, children between the ages of 2 and 3 need 1,000 to 1,400 calories, while children between the ages of 4 and 8 need 1,200 to 2,000 calories (Mayo Clinic, 2016a).

Toilet Training

Toilet training typically occurs during the first two years of early childhood (24-36 months). Some children show interest by age 2, but others may not be ready until months later. The average age for girls to be toilet trained is 29 months and for boys it is 31 months, and 98% of children are trained by 36 months (Boyse & Fitzgerald, 2010). The child’s age is not as important as his/her physical and emotional readiness. If started too early, it might take longer to train a child. According to The Mayo Clinic (2016b) the following questions can help parents determine if a child is ready for toilet training:

- Does your child seem interested in the potty chair or toilet, or in wearing underwear?

- Can your child understand and follow basic directions?

- Does your child tell you through words, facial expressions or posture when he or she needs to go?

- Does your child stay dry for periods of two hours or longer during the day?

- Does your child complain about wet or dirty diapers?

- Can your child pull down his or her pants and pull them up again?

- Can your child sit on and rise from a potty chair? (p. 1)

If a child resists being trained or is not successful after a few weeks, it is best to take a break and try again later. Most children master daytime bladder control first, typically within two to three months of consistent toilet training. However, nap and nighttime training might take months or even years.

Some children experience elimination disorders that may require intervention by the child’s pediatrician or a trained mental health practitioner. Elimination disorders include enuresis, or the repeated voiding of urine into bed or clothes (involuntary or intentional) and encopresis, the repeated passage of feces into inappropriate places (involuntary or intentional) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The prevalence of enuresis is 5%-10% for 5 year-olds, 3%-5% for 10 year-olds, and approximately 1% for those 15 years of age or older. Around 1% of 5 year- olds have encopresis, and it is more common in males than females.

Sleep

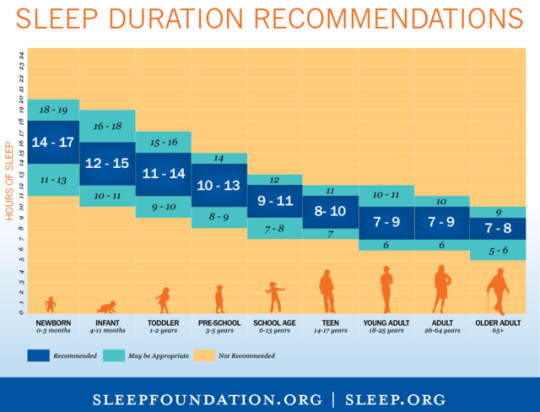

During early childhood, there is wide variation in the number of hours of sleep recommended per day. For example, two-year-olds may still need 15-16 hours per day, while a six-year-old may only need 7-8 hours. The National Sleep Foundation’s 2015 recommendations based on age are listed in the figure below.

Piaget

According to Piaget, the preoperational stage is associated with early childhood and occurs from 2 to 7 years of age. In this stage, children use symbols to represent words, images, and ideas, which is why children in this stage tend to engage in pretend play. A child’s arms might become airplane wings as she zooms around the room, or a child with a stick might become a brave knight with a sword. Children also begin to use language in the preoperational stage, but they cannot typically understand adult logic. The term operational refers to logical manipulation of information, so children at this stage are considered pre-operational. Children’s logic is based on their own personal knowledge of the world so far, rather than on conventional knowledge.[2]

Video Example

Watch this video illustrating children’s accurate portrayal of Piaget’s preoperational thinking

The preoperational period is divided into two stages: The Symbolic Function Substage occurs between 2 and 4 years of age and is characterized by the child being able to mentally represent an object that is not present and a dependence on perception in problem solving. The Intuitive Thought Substage, lasting from 4 to 7 years, is marked by greater dependence on intuitive thinking rather than just perception (Thomas, 1979). At this stage, children ask many questions as they attempt to understand the world around them using immature reasoning. Let’s examine some of Piaget’s assertions about children’s cognitive abilities at this age.

Pretend Play

Pretending is a favorite activity at this time. A toy has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything originally intended. A teddy bear, for example, can be a baby or the queen of a faraway land. Piaget believed that children’s pretend play helped children solidify new schemata they were developing cognitively. This play, then, reflected changes in their conceptions or thoughts. However, children also learn as they pretend and experiment. Their play does not simply represent what they have learned (Berk, 2007).

Egocentrism

Egocentrism in early childhood refers to the tendency of young children not to be able to take the perspective of others. Instead, the child thinks that everyone sees, thinks, and feels just as they do. An egocentric child is not able to infer the perspective of other people and instead attributes his own perspective to situations. For example, ten-year-old Keiko’s birthday is coming up, so her mom takes 3-year-old Kenny to the toy store to choose a present for his sister. He selects an Iron Man action figure for her, thinking that if he likes the toy, his sister will too.

Piaget’s classic experiment on egocentrism involved showing children a three dimensional model of a mountain and asking them to describe what a doll that is looking at the mountain from a different angle might see (see Figure 4.9). Children tend to choose a picture that represents their own, rather than the doll’s view. By age 7 children are less self-centered.

However, even younger children when speaking to others tend to use different sentence structures and vocabulary when addressing a younger child or an older adult. This indicates some awareness of the views of others.

Conservation Errors

Conservation refers to the ability to recognize that moving or rearranging matter does not change the quantity. Let’s look at Kenny and Keiko again. Dad gave a slice of pizza to 10-year-old Keiko and another slice to 3-year-old Kenny. Kenny’s pizza slice was cut into five pieces, so Kenny told his sister that he got more pizza than she did. Kenny did not understand that cutting the pizza into smaller pieces did not increase the overall amount. This was because Kenny exhibited Centration, or focused on only one characteristic of an object to the exclusion of others. Kenny focused on the five pieces of pizza to his sister’s one piece even though the total amount was the same. Keiko was able to consider several characteristics of an object than just one. Because children have not developed this understanding of conservation, they cannot perform mental operations.

The classic Piagetian experiment associated with conservation involves liquid (Crain, 2005). As seen in Figure 4.10, the child is shown two glasses (as shown in a) which are filled to the same level and asked if they have the same amount. Usually the child agrees they have the same amount.

The experimenter then pours the liquid in one glass to a taller and thinner glass (as shown in b). The child is again asked if the two glasses have the same amount of liquid. The preoperational child will typically say the taller glass now has more liquid because it is taller (as shown in c). The child has centrated on the height of the glass and fails to conserve.

Video Example

Watch this video illustrating children’s classification errors (they have not yet mastered all parts of Piaget’s conservation tasks)

Classification Errors: Preoperational children have difficulty understanding that an object can be classified in more than one way. For example, if shown three white buttons and four black buttons and asked whether there are more black buttons or buttons, the child is likely to respond that there are more black buttons. They do not consider the general class of buttons. As the child’s vocabulary improves and more schemata are developed, the ability to classify objects improves.

Animism refers to attributing life-like qualities to objects. The cup is alive, the chair that falls down and hits the child’s ankle is mean, and the toys need to stay home because they are tired. Cartoons frequently show objects that appear alive and take on lifelike qualities. Young children do seem to think that objects that move may be alive, but after age three, they seldom refer to objects as being alive (Berk, 2007).

Critiques of Piaget

Similar to the critique of the sensorimotor period, several psychologists have attempted to show that Piaget also underestimated the intellectual capabilities of the preoperational child. For example, children’s specific experiences can influence when they are able to conserve. Children of pottery makers in Mexican villages know that reshaping clay does not change the amount of clay at much younger ages than children who do not have similar experiences (Price-Williams, Gordon, & Ramirez, 1969). Crain (2005) indicated that preoperational children can think rationally on mathematical and scientific tasks, and they are not as egocentric as Piaget implied. Research on Theory of Mind (discussed later in the chapter) has demonstrated that children overcome egocentrism by 4 or 5 years of age, which is sooner than Piaget indicated.

Children’s Understanding of the World

Both Piaget and Vygotsky believed that children actively try to understand the world around them. More recently, developmentalists have added to this understanding by examining how children organize information and develop their own theories about the world.

Theory of mind refers to the ability to think about other people’s thoughts. This mental mind reading helps humans to understand and predict the reactions of others, thus playing a crucial role in social development. One common method for determining if a child has reached this mental milestone is the false belief task, described below.

The research began with a clever experiment by Wimmer and Perner (1983), who tested whether children can pass a false-belief test (see Figure 4.17). The child is shown a picture story of Sally, who puts her ball in a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is out of the room, Anne comes along and takes the ball from the basket and puts it inside a box. The child is then asked where Sally thinks the ball is located when she comes back to the room. Is she going to look first in the box or in the basket? The right answer is that she will look in the basket, because that’s where she put it and thinks it is; but we have to infer this false belief against our own better knowledge that the ball is in the box. This is very difficult for children before the age of four because of the cognitive effort it takes. Three-year-olds have difficulty distinguishing between what they once thought was true and what they now know to be true. They feel confident that what they know now is what they have always known (Birch & Bloom, 2003).

Even adults need to think through this task (Epley, Morewedge, & Keysar, 2004). To be successful at solving this type of task the child must separate what he or she “knows” to be true from what someone else might “think” is true. In Piagetian terms, they must give up a tendency toward egocentrism. The child must also understand that what guides people’s actions and responses are what they “believe” rather than what is reality. In other words, people can mistakenly believe things that are false and will act based on this false knowledge. Consequently, prior to age four children are rarely successful at solving such a task (Wellman, Cross & Watson, 2001).

Language Development

A child’s vocabulary expands between the ages of two to six from about 200 words to over 10,000 words. This “vocabulary spurt” typically involves 10-20 new words per week and is accomplished through a process called fast-mapping. Words are easily learned by making connections between new words and concepts already known. The parts of speech that are learned depend on the language and what is emphasized. Children speaking verb-friendly languages, such as Chinese and Japanese, learn verbs more readily, while those speaking English tend to learn nouns more readily. However, those learning less verb-friendly languages, such as English, seem to need assistance in grammar to master the use of verbs (Imai et al., 2008).

Literal meanings

Children can repeat words and phrases after having heard them only once or twice, but they do not always understand the meaning of the words or phrases. This is especially true of expressions or figures of speech which are taken literally. For example, a classroom full of preschoolers hears the teacher say, “Wow! That was a piece of cake!” The children began asking “Cake? Where is my cake? I want cake!”

Overregularization

Children learn rules of grammar as they learn language but may apply these rules inappropriately at first. For instance, a child learns to add “ed” to the end of a word to indicate past tense. Then form a sentence such as “I goed there. I doed that.” This is typical at ages two and three. They will soon learn new words such as “went” and “did” to be used in those situations.

The Impact of Training

Remember Vygotsky and the Zone of Proximal Development? Children can be assisted in learning language by others who listen attentively, model more accurate pronunciations, and encourage elaboration. The child exclaims, “I’m goed there!” and the adult responds, “You went there? Say, ‘I went there.’ Where did you go?” Children may be ripe for language as Chomsky suggests, but active participation in helping them learn is important for language development as well. The process of scaffolding is one in which the guide provides needed assistance to the child as a new skill is learned.

Preschool

Providing universal preschool has become an important lobbying point for federal, state, and local leaders throughout our country. In his 2013 State of the Union address, President Obama called upon Congress to provide high-quality preschool for all children. He continued to support universal preschool in his legislative agenda, and in December 2014 the President convened state and local policymakers for the White House Summit on Early Education (White House Press Secretary, 2014). However, universal preschool covering all four-year-olds in the country would require significant funding. Further, how effective preschools are in preparing children for elementary school, and what constitutes high-quality preschool have been debated. To set criteria for designation as a high quality preschool, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) identifies 10 standards (NAEYC, 2016). These include:

- Positive relationships among all children and adults are promoted.

- A curriculum that supports learning and development in social, emotional, physical, language, and cognitive areas.

- Teaching approaches that are developmentally, culturally, and linguistically appropriate.

- Assessment of children’s progress to provide information on learning and development.

- The health and nutrition of children are promoted, while they are protected from illness and injury.

- Teachers possess the educational qualifications, knowledge, and commitment to promote children’s learning.

- Collaborative relationships with families are established and maintained.

- Relationships with agencies and institutions in the children’s communities are established to support the program’s goals.

- Indoor and outdoor physical environments are safe and well-maintained.

- Leadership and management personnel are well qualified, effective, and maintain licensure status with the applicable state agency.

Parents should review preschool programs using the NAEYC criteria as a guide and template for asking questions that will assist them in choosing the best program for their child. Selecting the right preschool is also difficult because there are so many types of preschools available. Zachry (2013) identified Montessori, Waldorf, Reggio Emilia, High Scope, Parent Co-Ops, and Bank Street as types of preschool programs that focus on children learning through discovery. Teachers act as guides and create activities based on the child’s developmental level.

Head Start

For children who live in poverty, Head Start has been providing preschool education since 1965 when it was begun by President Lyndon Johnson as part of his war on poverty. It currently serves nearly one million children and annually costs approximately 7.5 billion dollars (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2015).

However, concerns about the effectiveness of Head Start have been ongoing since the program began. Armor (2015) reviewed existing research on Head Start and found there were no lasting gains, and the average child in Head Start had not learned more than children who did not receive preschool education.

A recent report dated July 2015 evaluating the effectiveness of Head Start comes from the What Works Clearinghouse. The What Works Clearinghouse identifies research that provides reliable evidence of the effectiveness of programs and practices in education and is managed by the Institute of Education Services for the United States Department of Education. After reviewing 90 studies on the effectiveness of Head Start, only one study was deemed scientifically acceptable and this study showed disappointing results (Barshay, 2015). This study showed that 3 and 4-year-old children in Head Start received “potentially positive effects” on general reading achievement, but no noticeable effects on math achievement and social-emotional development.

Nonexperimental designs are a significant problem in determining the effectiveness of Head Start programs because a control group is needed to show group differences that would demonstrate educational benefits. Because of ethical reasons, low-income children are usually provided with some type of preschool programming in an alternative setting. Additionally, head Start programs are different depending on the location, and these differences include the length of the day or qualification of the teachers. Lastly, testing young children is difficult and strongly dependent on their language skills and comfort level with an evaluator (Barshay, 2015).

Autism Spectrum Disorder in Early Childhood

A greater discussion on disorders affecting children and special educational services to assist them will occur in chapter 5. However, because characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder must be present in the early developmental period, as established by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013), this disorder will be presented here.

Autism spectrum disorder is probably the most misunderstood and puzzling of neurodevelopmental disorders. Children with this disorder show signs of significant disturbances in three main areas: (a) deficits in social interaction, (b) deficits in communication, and (c) repetitive patterns of behavior or interests. These disturbances appear early in life and cause serious impairments in functioning (APA, 2013). The child with autism spectrum disorder might exhibit deficits in social interaction by not initiating conversations with other children or turning their head away when spoken to. These children do not make eye contact with others and seem to prefer playing alone rather than with others. In a certain sense, it is almost as though these individuals live in a personal and isolated social world others are simply not privy to or able to penetrate. Communication deficits can range from a complete lack of speech, to one word responses (e.g., saying “Yes” or “No” when replying to questions or statements that require additional elaboration), to echoed speech (e.g., parroting what another person says, either immediately or several hours or even days later), to difficulty maintaining a conversation because of an inability to reciprocate others’ comments. These deficits can also include problems in using and understanding nonverbal cues (e.g., facial expressions, gestures, and postures) that facilitate normal communication.

Repetitive patterns of behavior or interests can be exhibited a number of ways. The child might engage in stereotyped, repetitive movements (rocking, head-banging, or repeatedly dropping an object and then picking it up), or she might show great distress at small changes in routine or the environment. For example, the child might throw a temper tantrum if an object is not in its proper place or if a regularly- scheduled activity is rescheduled. In some cases, the person with autism spectrum disorder might show highly restricted and fixated interests that appear to be abnormal in their intensity. For instance, the child might learn and memorize every detail about something even though doing so serves no apparent purpose. Importantly, autism spectrum disorder is not the same thing as intellectual disability, although these two conditions can occur together. The DSM-5 specifies that the symptoms of autism spectrum disorder are not caused or explained by intellectual disability.

The qualifier “spectrum” in autism spectrum disorder is used to indicate that individuals with the disorder can show a range, or spectrum, of symptoms that vary in their magnitude and severity: Some severe, others less severe. The previous edition of the DSM included a diagnosis of Asperger’s disorder, generally recognized as a less severe form of autistic disorder; individuals diagnosed with Asperger’s disorder were described as having average or high intelligence and a strong vocabulary, but exhibiting impairments in social interaction and social communication, such as talking only about their special interests (Wing, Gould, & Gillberg, 2011). However, because research has failed to demonstrate that Asperger’s disorder differs qualitatively from autistic disorder, the DSM-5 does not include it. Some individuals with autism spectrum disorder, particularly those with better language and intellectual skills, can live and work independently as adults. However, most do not because the symptoms remain sufficient to cause serious impairment in many realms of life (APA, 2013).

Currently, estimates indicate that nearly 1 in 88 children in the United States has autism spectrum disorder; the disorder is 5 times more common in boys (1 out of 54) than girls (1 out of 252) (CDC, 2012). Rates of autistic spectrum disorder have increased dramatically since the 1980s. Although it is difficult to interpret this increase, it is possible that the rise in prevalence is the result of the broadening of the diagnosis, increased efforts to identify cases in the community, and greater awareness and acceptance of the diagnosis. In addition, mental health professionals are now more knowledgeable about autism spectrum disorder and are better equipped to make the diagnosis, even in subtle cases (Novella, 2008).

The exact causes of autism spectrum disorder remain unknown despite massive research efforts over the last two decades (Meek, Lemery-Chalfant, Jahromi, & Valiente, 2013). Autism appears to be strongly influenced by genetics, as identical twins show concordance rates of 60%– 90%, whereas concordance rates for fraternal twins and siblings are 5%–10% (Autism Genome Project Consortium, 2007). Many different genes and gene mutations have been implicated in autism (Meek et al., 2013). Among the genes involved are those important in the formation of synaptic circuits that facilitate communication between different areas of the brain (Gauthier et al., 2011). A number of environmental factors are also thought to possibly be associated with increased risk for autism spectrum disorder, at least in part, because they contribute to new mutations. These factors include exposure to pollutants, such as plant emissions and mercury, urban versus rural residence, and vitamin D deficiency (Kinney, Barch, Chayka, Napoleon, & Munir, 2009).

There is no scientific evidence that a link exists between autism and vaccinations (Hughes, 2007). Indeed, a recent study compared the vaccination histories of 256 children with autism spectrum disorder with that of 752 control children across three time periods during their first two years of life (birth to 3 months, birth to 7 months, and birth to 2 years) (DeStefano, Price, & Weintraub, 2013). At the time of the study, the children were between 6 and 13 years old, and their prior vaccination records were obtained. Because vaccines contain immunogens (substances that fight infections), the investigators examined medical records to see how many immunogens children received to determine if those children who received more immunogens were at greater risk for developing autism spectrum disorder. The results of this study clearly demonstrated that the quantity of immunogens from vaccines received during the first two years of life were not at all related to the development of autism spectrum disorder.

Erikson: Initiative versus Guilt

The trust and autonomy of previous stages develop into a desire to take initiative or to think of ideas and initiative action (Erikson, 1982). Children may want to build a fort with the cushions from the living room couch or open a lemonade stand in the driveway or make a zoo with their stuffed animals and issue tickets to those who want to come. Or they may just want to get themselves ready for bed without any assistance. To reinforce taking initiative, caregivers should offer praise for the child’s efforts and avoid being critical of messes or mistakes. Placing pictures of drawings on the refrigerator, purchasing mud pies for dinner, and admiring towers of legos will facilitate the child’s sense of initiative.

Sibling Relationships

Siblings spend a considerable amount of time with each other and offer a unique relationship that is not found with same-age peers or with adults. Siblings play an important role in the development of social skills. Cooperative and pretend play interactions between younger and older siblings can teach empathy, sharing, and cooperation (Pike, Coldwell, & Dunn, 2005), as well as, negotiation and conflict resolution (Abuhatoum & Howe, 2013). However, the quality of sibling relationships is often mediated by the quality of the parent-child relationship and the psychological adjustment of the child (Pike et al., 2005). For instance, more negative interactions between siblings have been reported in families where parents had poor patterns of communication with their children (Brody, Stoneman, & McCoy, 1994). Children who have emotional and behavioral problems are also more likely to have negative interactions with their siblings. However, the psychological adjustment of the child can sometimes be a reflection of the parent-child relationship. Thus, when examining the quality of sibling interactions, it is often difficult to tease out the separate effect of adjustment from the effect of the parent-child relationship.

While parents want positive interactions between their children, conflicts are going to arise, and some confrontations can be the impetus for growth in children’s social and cognitive skills. The sources of conflict between siblings often depend on their respective ages. Dunn and Munn (1987) revealed that over half of all sibling conflicts in early childhood were disputes about property rights. By middle childhood this starts shifting toward control over social situations, such as what games to play, disagreements about facts or opinions, or rude behavior (Howe, Rinaldi, Jennings, & Petrakos, 2002). Researchers have also found that the strategies children use to deal with conflict change with age, but that this is also tempered by the nature of the conflict. Abuhatoum and Howe (2013) found that coercive strategies (e.g., threats) were preferred when the dispute centered on property rights, while reasoning was more likely to be used by older siblings and in disputes regarding control over the social situation. However, younger siblings also use reasoning, frequently bringing up the concern of legitimacy (e.g., “You’re not the boss”) when in conflict with an older sibling. This is a very common strategy used by younger siblings and is possibly an adaptive strategy in order for younger siblings to assert their autonomy (Abuhatoum & Howe, 2013). A number of researchers have found that children who can use non-coercive strategies are more likely to have a successful resolution, whereby a compromise is reached and neither child feels slighted (Ram & Ross, 2008; Abuhatoum & Howe, 2013).

Not surprisingly, friendly relationships with siblings often lead to more positive interactions with peers. The reverse is also true. A child can also learn to get along with a sibling, with, as the song says “a little help from my friends” (Kramer & Gottman, 1992).

References

- Abuhatoum, S., & Howe, N. (2013). Power in sibling conflict during early and middle childhood. Social Development, 22, 738- 754.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V). Washington, DC: Author.

- Ariès, P. (1962). Centuries of childhood; a social history of family life. New York: Knopf.

- Armor, D. J. (2015). Head start or false start. USA Today Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.questia.com/magazine/1G1-429736352/head-start-or-false-start

- Autism Genome Project Consortium. (2007). Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nature Genetics, 39, 319–328.

- Barshay, J. (2015). Report: Scant scientific evidence for Head Start programs’ effectiveness. U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved from http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/ 2015/08/03/report-scant-scientific-evidence-for-head-start- programs-effectiveness

- Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 4(1), part 2.

- Baumrind, D. (2013). Authoritative parenting revisited: History and current status. In R. E. Larzelere, A. Sheffield, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.). Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 11- 34). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Berk, L. E. (2007). Development through the life span (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Berwid, O., Curko-Kera, E. A., Marks, D. J., & Halperin, J. M. (2005). Sustained attention and response inhibition in young children at risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(11), 1219-1229.

- Bibok, M.B., Carpendale, J.I.M., & Muller, U. (2009). Parental scaffolding and the development of executive function. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 123, 17-34.

- Birch, S., & Bloom, P. (2003). Children are cursed: An asymmetric bias in mental-state attribution. Psychological Science, 14(3), 283-286.

- Boyse, K. & Fitgerald, K. (2010). Toilet training. University of Michigan Health System. Retrieved from http://www.med.umich.edu/yourchild/topics/toilet.htm

- Brody, G. H., Stoneman, Z., & McCoy, J. K. (1994). Forecasting sibling relationships in early adolescence from child temperament and family processes in middle childhood. Child development, 65, 771-784.

- Brown, G.L., Mangelsdork, S.C., Agathen, J.M., & Ho, M. (2008). Young children’s psychological selves: Convergence with maternal reports of child personality. Social Development, 17, 161-182.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2015). Women in the labor force: A databook. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-databook/archive/women-in-the-labor-force-a-databook-2015.pdf

- Byrd, R. (2002). Report to the legislature on the principal findings from the epidemiology of autism in California: A comprehensive pilot study. Retrieved from http://www.dds.ca.gov/Autism/MindReport.cfm

- Carroll, J. L. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2000). 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_11/sr11_246.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders, autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries, 61(3), 1–19. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6103.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Nutrition and health of young people. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/nutrition/facts.htm

- Christakis, D.A. (2009). The effects of infant media usage: what do we know and what should we learn? Acta Paediatrica, 98, 8– 16.

- Clark, J. (1994). Motor development. In V. S.Ramachandran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (pp. 245–255). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Colwell, M.J., & Lindsey, E.W. (2003). Teacher-child interactions and preschool children’s perceptions of self and peers. Early Childhood Development & Care, 173, 249-258.

- Coté, C. A., & Golbeck, S. (2007). Preschoolers’ feature placement on own and others’ person drawings. International Journal of Early Years Education, 15(3), 231-243.

- Courage, M.L., Murphy, A.N., & Goulding, S. (2010). When the television is on: The impact of infant-directed video on 6- and 18-month-olds’ attention during toy play and on parent-infant interaction. Infant Behavior and Development, 33, 176- 188.

- Crain, W. (2005). Theories of development concepts and applications (5th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

- DeStefano, F., Price, C. S., & Weintraub, E. S. (2013). Increasing exposures to antibody-stimulating proteins and polysaccharides in vaccines is not associated with risk of autism. The Journal of Pediatrics, 163, 561–567.

- Dougherty, D.M., Marsh, D.M., Mathias, C.W., & Swann, A.C. (2005). The conceptualization of impulsivity: Bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Psychiatric Times, 22(8), 32-35.

- Dunn, J., & Munn, P. (1987). Development of justification in disputes with mother and sibling. Developmental Psychology, 23, 791-798.

- Dyer, S., & Moneta, G. B. (2006). Frequency of parallel, associative, and cooperative play in British children of different socio- economic status. Social Behavior and Personality, 34(5), 587-592.

- Epley, N., Morewedge, C. K., & Keysar, B. (2004). Perspective taking in children and adults: Equivalent egocentrism but differential correction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 760–768.

- Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. NY: Norton & Company.

- Evans, D. W., Gray, F. L., & Leckman, J. F. (1999). The rituals, fears and phobias of young children: Insights from development, psychopathology and neurobiology. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 29(4), 261-276.

- Evans, D. W. & Leckman, J. F. (2015) Origins of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Developmental and Evolutionary Perspectives. In D. Cicchetti and D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental Psychopathology (2nd edition). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

- Farah, M. J., Rabinowitz, C., Quinn, G. E., & Liu, G. T. (2000). Early commitment of neural substrates for face recognition. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 17(1–3), 117–123.

- Fay-Stammbach, T., Hawes, D. J., & Meredith, P. (2014). Parenting influences on executive function in early childhood: A review. Child Development Perspectives, 8(4), 258-264.

- Finkelhorn, D., Hotaling, G., Lewis, I. A., & Smith, C. (1990). Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse and Neglect, 14(1), 19-28.

- Frank, G., Plunkett, S. W., & Otten, M. P. (2010). Perceived parenting, self-esteem, and general self-efficacy of Iranian American adolescents. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 19, 738-746.

- Garrett, B. (2015). Brain and behavior: An introduction to biological psychology (4th Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Gauthier, J., Siddiqui, T. J., Huashan, P., Yokomaku, D., Hamdan, F. F., Champagne, N., . . . Rouleau, G.A. (2011). Truncating mutations in NRXN2 and NRXN1 in autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Human Genetics, 130, 563–573.

- Gecas, V., & Seff, M. (1991). Families and adolescents. In A. Booth (Ed.), Contemporary families: Looking forward, looking back. Minneapolis, MN: National Council on Family Relations.

- Gentile, D.A., & Walsh, D.A. (2002). A normative study of family media habits. Applied Developmental Psychology, 23, 157- 178.

- Gernhardt, A., Rubeling, H., & Keller, H. (2015). Cultural perspectives on children’s tadpole drawings: At the interface between representation and production. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 812. doi: 0.3389/fpsyg.2015.00812.

- Gershoff, E. T. (2008). Report on physical punishment in the United States: What research tell us about its effects on children. Columbus, OH: Center for Effective Discipline.

- Glass, E., Sachse, S., & von Suchodoletz, W. (2008). Development of auditory sensory memory from 2 to 6 years: an MMN study. Journal of Neural Transmission, 115(8), 1221-1229. doi:10.1007/s00702-008-0088-6

- Gleason, T. R. (2002). Social provisions of real and imaginary relationships in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 38, 979-992.

- Gleason, T. R., & Hohmann, L. M. (2006). Concepts of real and imaginary friendships in ear-ly childhood. Social Development, 15, 128-144.

- Gleason, T. R., Sebanc, A. M., & Hartup, W. W. (2000). Imaginary companions of preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 36(4), 419-428.

- Gomes, G. Sussman, E., Ritter, W., Kurtzberg, D., Vaughan, H. D. Jr., & Cowen, N. (1999). Electrophysiological evidence of development changes in the duration of auditory sensory memory. Developmental Psychology, 35, 294-302.

- Goodvin, R., Meyer, S. Thompson, R.A., & Hayes, R. (2008). Self-understanding in early childhood: associations with child attachment security and maternal negative affect. Attachment & Human Development, 10(4), 433-450.

- Gopnik, A., & Wellman, H.M. (2012). Reconstructing constructivism: Causal models, Bayesian learning mechanisms, and the theory theory. Psychological Bulletin, 138(6), 1085-1108.

- Guy, J., Rogers, M., & Cornish, K. (2013). Age-related changes in visual and auditory sustained attention in preschool-aged children. Child Neuropsychology, 19(6), 601–614. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2012.710321

- Harter, S., & Pike, R. (1984). The pictorial scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children. Child Development, 55, 1969-1982.

- Herrmann, E., Misch, A., Hernandez-Lloreda, V., & Tomasello, M. (2015). Uniquely human self-control begins at school age. Developmental Science. 18(6), 979-993. doi:10.1111/desc.12272.

- Herrmann, E., & Tomasello, M. (2015). Focusing and shifting attention in human children (homo sapiens) and chimpanzees (pan troglodytes). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 129(3), 268–274. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0039384

- Howe, N., Rinaldi, C. M., Jennings, M., & Petrakos, H. (2002). “No! The lambs can stay out because they got cozies”: Constructive and destructive sibling conflict, pretend play, and social understanding. Child Development, 73, 1406- 1473.

- Hughes, V. (2007). Mercury rising. Nature Medicine, 13, 896-897.

- Imai, M., Li, L., Haryu, E., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Shigematsu, J. (2008). Novel noun and verb learning in Chinese, English, and Japanese children: Universality and language-specificity in novel noun and verb learning. Child Development, 79, 979-1000.

- Jones, P.R., Moore, D.R., & Amitay, S. (2015). Development of auditory selective attention: Why children struggle to hear in noisy environments. Developmental Psychology, 51(3), 353–369. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038570

- Kalat, J. W. (2016). Biological Psychology (12th Ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage.

- Kellogg, R. (1969). Handbook for Rhoda Kellogg: Child art collection. Washington D. C.: NCR/Microcard Editions.

- Kemple, K.M., (1995). Shyness and self-esteem in early childhood. Journal of Humanistic Education and Development, 33(4), 173-182.

- Kimmel, M. S. (2008). The gendered society (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kinney, D. K., Barch, D. H., Chayka, B., Napoleon, S., & Munir, K. M. (2009). Environmental risk factors for autism: Do they help or cause de novo genetic mutations that contribute to the disorder? Medical Hypotheses, 74, 102–106.

- Kirkorian, H.L., Pempek, T.A., & Murphy, L.A. (2009). The impact of background television on parent-child interaction. Child Development, 80, 1350-1359.

- Kohn, M. L. (1977). Class and conformity. (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kolb, B., & Fantie, B. (1989). Development of the child’s brain and behavior. In C. R. Reynolds & E. Fletcher-Janzen (Eds.), Handbook of clinical child neuropsychology (pp. 17–39). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Kolb, B. & Whishaw, I. Q. (2011). An introduction to brain and behavior (3rd ed.). New York: Worth Publishers.

- Kramer, L., & Gottman, J. M. (1992). Becoming a sibling: “With a little help from my friends.” Developmental Psychology, 28, 685-699.

- Lenroot, R. K., & Giedd, J. N. (2006). Brain development in children and adolescents: Insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 30, 718-729.

- Maccoby, E., & Jacklin, C. (1987). Gender segregation in childhood. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 20, 239-287.

- MacKenzie, M. J., Nicklas, E., Waldfogel, J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2013). Spanking and child development across the first decade of life. Pediatrics, 132(5), e1118-e1125.

- Manosevitz, M., Prentice, N. M., & Wilson, F. (1973). Individual and family correlates of imaginary companions in preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 8, 72-79.

- Martinson, F. M. (1981). Eroticism in infancy and childhood. In L. L. Constantine & F. M. Martinson (Eds.), Children and sex: New findings, new perspectives. (pp. 23-35). Boston: Little, Brown.

- Masih, V. (1978). Imaginary play companions of children. In R. Weizman, R. Brown, P. Levinson, & P. Taylor (Eds.). Piagetian theory and the helping profession (pp. 136-144). Los Angeles: University of Southern California Press.

- Mauro, J. (1991). The friend that only I can see: A longitudinal investigation of children’s imaginary companions. Dissertation, University of Oregon.

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2016a). Nutrition for kids: Guidelines for a healthy diet. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy- lifestyle/childrens-health/in-depth/nutrition-for-kids/art-20049335

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2016b). Potty training: How to get the job done. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy- lifestyle/infant-and-toddler-health/indepth/potty-training/art-20045230

- McAlister, A. R., & Peterson, C. C. (2007). A longitudinal study of siblings and theory of mind development. Cognitive Development, 22, 258-270.

- Meek, S. E., Lemery-Chalfant, K., Jahromi, L. D., & Valiente, C. (2013). A review of gene-environment correlations and their implications for autism: A conceptual model. Psychological Review, 120, 497–521.

- Middlebrooks, J. S., & Audage, N. C. (2008). The effects of childhood stress on health across the lifespan. (United States, Center for Disease Control, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control). Atlanta, GA.

- Mischel, W., Ayduk, O., Berman, M. G., Casey, B. J., Gotlib, I. H., Jonides, J., & … Shoda, Y. (2011). ‘Willpower’ over the life span: decomposing self-regulation. Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience, 6(2), 252-256. doi:10.1093/scan/nsq081

- Mischel, W., Ebbesen, E. B., & Zeiss, A. R. (1972). Cognitive and attentional mechanisms in delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21, 204–218.

- Morra, S., Gobbo, C., Marini, Z., & Sheese, R. (2008). Cognitive development Neo-Piagetian perspectives. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2016). The 10 NAEYC program standards. Retrieved from http://families.naeyc.org/accredited-article/10-naeyc-program-standards

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2006). The NICHD study of early child care (NIH Pub. No. 05- 4318). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Nelson, K., & Fivush, R. (2004). The emergence of sutobiographical memory: A social cultural developmental theory. Psychological Review, 111(2), 468-511.

- Nelson, K., & Ross, G. (1980). The generalities and specifics of long-term memory in infants and young children. In M. Perlmutter (Ed.), Children’s memory: New directions in child development (Vol. 10, pp. 87-101). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Nielsen Company. (2009).Television Audience 2008-2009. Retrieved from http://blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/tva_2008_071709.pdf

- Novella, S. (2008). The increase in autism diagnoses: Two hypotheses [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/the-increase-in-autism-diagnoses-two-hypotheses/

- Okami, P., Olmstead, R., & Abramson, P. R. (1997). Sexual experiences in early childhood: 18-year longitudinal data from UCLA Family Lifestyles Project. Journal of Sex Research, 34(4), 339-347.

- Parten, M. B. (1932). Social participation among preschool children. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 27, 243-269. Perner, J., Ruffman, T., & Leekam, S. R. (1994). Theory of mind is contagious: You catch from your sibs. Child Development, 65, 1228-1238.

- Pike, A., Coldwell, J., & Dunn, J. F. (2005). Sibling relationships in early/middle childhood: Links with individual adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(4), 523-532.

- Porporino, M., Shore, D.I., Iarocci, G., & Burack, J.A. (2004). A developmental change in selective attention and global form perception. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28 (4), 358–364 DOI: 10.1080/01650250444000063

- Posner, M.I., & Rothbart, M.K. (2007). Research on attention networks as a model for the integration of psychological science. Annual Review in Psychology. 58, 1–23.

- Price-Williams, D.R., Gordon, W., & Ramirez, M. (1969). Skill and conservation: A study of pottery making children. Developmental Psychology, 1, 769.

- Ram, A., & Ross, H. (2008). “We got to figure it out”: Information-sharing and siblings’ negotiations of conflicts of interest. Social Development, 17, 512-527.

- Rice, F. P. (1997). Human development: A life-span approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Rideout, V.J., & Hamel E. (2006). The media family: Electronic media in the lives of infants, toddlers, preschoolers and their parents. Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/7500.pdf

- Robinson, T.N., Wilde, M.L., & Navracruz, L.C. (2001). Effects of reducing children’s television and video game use on aggressive behavior: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 155, 17-23.

- Rothbart, M.K., & Rueda, M.R. (2005). The development of effortful control. In U. Mayr, E. Awh, & S.W. Keele (Eds.), Developing Individuality in the Human Brain: A Festschrift Honoring Michael I. Posner (pp. 167–88). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association

- Ruble, D.N., Boggiano, A.K., Feldman, N.S., & Loeble, J.H. (1980). Developmental analysis of the role of social comparison in self-evaluation. Developmental Psychology, 16, 105-115.

- Ruble, D. N., Martin, C., & Berenbaum, S. (2006). Gender development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 858–932). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Russo, F. (2016). Debate growing about how to meet the urgent needs of transgender kids. Scientific American Mind, 27(1), 27- 35.

- Sadker, M., & Sadker, D. M. (1994). Failing at fairness: How America’s schools cheat girls. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons. Sandberg, J. F., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Changes in children’s time with parents: United States, 1981-1997. Demography, 38, 423-436.

- Schmidt, M.E., Pempek, T.A., & Kirkorian, H.L. (2008). The effects of background television on the toy play behavior of very young children. Child Development, 79, 1137-1151.

- Schneider, W., Kron-Sperl, V., & Hunnerkopf, M. (2009). The development of young children’s memory strategies: Evidence from the Würzburg longitudinal memory study. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 6(1), 70-99.

- Schwartz, I. M. (1999). Sexual activity prior to coitus initiation: A comparison between males and females. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 28(1), 63-69.

- Shahaeian, A., Peterson, C. C., Slaughter, V., & Wellman, H. M. (2011). Culture and the sequence of steps in theory of mind development. Developmental Psychology, 47(5), 1239-1247.

- Singer, D., & Singer, J. (1990). The house of make-believe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Smith, B. L. (2012). The case against spanking. Monitor on Psychology, 43(4), 60.

- Steele, B.F. (1986). Notes on the lasting effects of early child abuse throughout the life cycle. Child Abuse & Neglect 10(3), 283-291.

- Thomas, R. M. (1979). Comparing theories of child development. Santa Barbara, CA: Wadsworth.

- Traverso, L., Viterbori, P., & Usai, M. C. (2015). Improving executive function in childhood: evaluation of a training intervention for 5-year-old children. Frontiers in Psychology, 61-14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00525

- United Nations. (2014). Committee on the rights of the child. Retrieved from http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CRC/Shared%20Documents/VAT/CRC_C_VAT_CO_2_16302_E.pdf

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2013). Child Maltreatment 2013. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2015). Head start program facts fiscal year 2013. Retrieved from http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/data/factsheets/docs/hs-program-fact-sheet-2013.pdf

- Valente, S. M. (2005). Sexual Abuse of Boys. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 18, 10–16. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6171.2005.00005.x

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Wellman, H.M., Cross, D., & Watson, J. (2001). Meta-analysis of theory of mind development: The truth about false belief. Child Development, 72(3), 655-684.

- Wellman, H. M., Fang, F., Liu, D., Zhu, L, & Liu, L. (2006). Scaling theory of mind understandings in Chinese children. Psychological Science, 17, 1075-1081.

- White House Press Secretary. (2014). Fact Sheet: Invest in US: The White House Summit on Early Childhood Education. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/12/10/fact-sheet-invest-us-white-house-summit- early-childhood-education

- Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition, 13, 103–128.

- Wing, L., Gould, J., & Gillberg, C. (2011). Autism spectrum disorders in the DSM-V: Better or worse than the DSM IV? Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 768–773.

- Zachry, A. (2013). 6 Types of Preschool Programs. Retrieved from http://www.parents.com/toddlers-preschoolers/starting – preschool/preparing/types-of-preschool-programs/

- This chapter is adapted from Lifespan Development by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French, licensed CC BY NC SA. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-lifespandevelopment/ ↵

- Adapted from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-lifespandevelopment/chapter/piagets-preoperational-stage-of-cognitive-development/ ↵