Module 5. Our Story: Asian Americans

Europeans have had a long-held fascination with the far East due to medieval travelers and traders like Marco Polo. For much of the early modern period, Spanish and Portuguese sailors attempted to find new trade routes to access the highly coveted exotic goods of the east. By the mid-16th century, Spanish explorers had much contact with Asians, and even employed some from their colonizing efforts in places like the Philippines. The earliest Asian arrivals to the North America were Filipino crew amongst the Spanish ships that landed in Northern California in the year 1587 (Lee, 2015). Due to Spanish colonization of the Americas, a mixture of Japanese, Chinese, and Filipino peoples migrated to South America during this era. Although Asians arrived with the Spanish, generally they were treated with much derision: paid less than Spanish sailors aboard these ships, given substandard living conditions and provisions.

By the early 19th century, a significant number of Asian immigrants, mostly Chinese, arrived in America. The motivation for migration was due to a variety of reasons, reasons that are called push and pull factors. A push factor would be something that compels an individual or group to leave a country, such as a political upheaval or armed conflict. A pull factor is a reason that would compel a person or group to enter a country, such as economic opportunity. The primary opportunity during this time for the Chinese to migrate to America was the Gold Rush.

The Gold Rush began when a new settler to California named James Marshall found a shiny substance in a riverbed in the year 1848. Thereafter, the scramble to pan and mine for gold became a global pull factor. Immigrants flocked from around the world and the U.S. to benefit from this discovery including many Chinese. Named for the year at the height of this rush, the “49ers” established towns, businesses, and laws to support this influx of people. Asian immigrants that made landfall on the west coast came in droves, but they faced obstacles linked to their countries of origin. Racial discrimination made it difficult to capitalize on the success of gold mining and panning, compared to other Americans and White immigrants.

The Chinese men who immigrated were immediately “othered” for their appearance. Many of them had a haircut called a que, which had a hairline shaved halfway up their scalps and worn in a long ponytail in the back. They wore clothes that appeared to be cotton pajamas to Americans, and they ate food with sticks (chopsticks) and strange sauces. These men were labeled “celestials” to complete their perception of strange and untrustworthiness. Lee Chew recounted the treatment of Chinese immigrants like himself, calling it “wrong and mean,” and that Chinese men were used only for “cheap labor.” Chew compared himself to other immigrants of the time like the Irish and Italians, and how the Chinese were unfairly denied citizenship or belonging as “law abiding, patriotic Americans” (Chew, 1882).

The start of the Gold Rush occurred when California was not yet annexed as a state, meaning it had no political officials, state constitution, or organized law enforcement. This was the “wild west,” and local sheriffs and deputies were often stretched thin, and law was enforced haphazardly. Venerable groups like the Chinese were offered little protection during this tenuous time, and these “celestials” were received with fear and hatred. This type of behavior is called xenophobia, a fear or hatred of foreigners. Often, this behavior erupted into violence upon the immigrant groups.

This tension would come to a head in events like the Chinese Massacre of 1871. Americans’ xenophobia led them to resort to violence to discourage the Chinese from settling permanently in America. Protests erupted in many cities to drive out these immigrants. In Los Angeles, tensions escalated into violence when Chinese men were accused to have killed two White men in the city, one of them a police officer. Chinese men were openly stalked and killed, resulting in 19 dead, and 15 later lynched by hanging.

Another instance of xenophobia were the events of the Snake River Massacre of 1887 when two small groups of Chinese men obtained mining permits in Oregon. White men conspired to attack these men, tracking them through the Oregon hills and systematically murdering them. An accurate number of the men killed is unknown since their bodies were left to the elements for an extended period and their gold stolen. The White perpetrators were brought to trial and later acquitted. This violent event was one of many that exhibits open violence against Asians with little to no consequences.

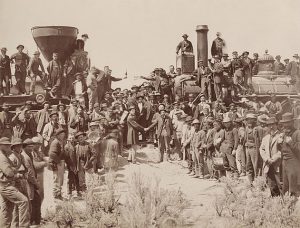

Despite having little success in gold mining, the Chinese found other ways to make a living in the U.S. In the 1860s, the Chinese found work mostly in the construction of railroads. These men did the most difficult and dangerous work, blasting rock with dynamite, clearing away the debris, shoveling and more. The achievement of the transcontinental railroad helped build the wealth of the U.S. during the 19th century, and 90 percent of its work was done by Chinese immigrants. When the railroad was completed in 1869, not one Chinese worker was present in the picture to commemorate the completion (Lee, 2015).

After much violence and conflict, Americans were ready to solidify their discrimination into legislation. Beginning in the 1860s, many laws were passed at local and state levels to prevent Asian immigrants from economic advancement. This eventually led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, a piece of legislation that would prevent Chinese immigrants from entering the US for 10 years unless entering for temporary stays related to business or education. The Chinese were also banned from obtaining naturalized citizenship, a law that would be challenged later.

Perhaps even more damaging was the Page Act, passed in 1875, which banned Asian women from entering the country because they were suspected of prostitution. This act had two ramifications. First, there was the implication that Asian women were suspected of sex work or corruption of society with promiscuity. Many lawmakers and others argued frequently at the time that both Asian men and women posed a sexual danger to American society. Secondly, it was very common for men to immigrate first, then send for the rest of their families. If wives attempted to enter the country after their husbands settled in the U.S., they faced an additional obstacle of being suspected of prostitution upon entry. Therefore, families were prevented from uniting as a result of this act, and Chinese women were blanketed with the label of promiscuity and sexual deviancy.

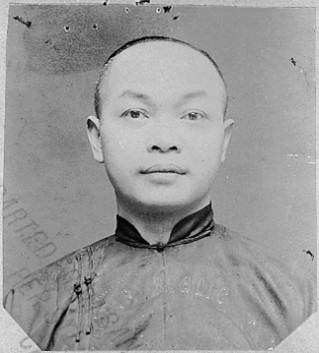

The Asians that were already in the country were treated with hostility and suspiciousness. The first picture identification cards were carried by the Chinese to identify them as foreign. Law makers in America then wondered, where do the Chinese and other Asians “fit” in society? Should they be Americanized, assimilated, or educated?

Asian immigrants and Asian Americans tried to fit in, acclimate to American society, and “become” American in a variety of ways. Methods included learning English, changing clothing and cultural practices, marrying Americans, and more. Most importantly, Asian Americans worked within the court systems in the U.S. to assert their civil rights. The following three cases illustrate some key court battles.

U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark (1898)

Wong Kim Ark was an American born Chinese man. His parents were born in China, but Ark was from California. In 1894, Ark took a trip to China to visit, and when he attempted to return to his home in San Francisco, he was denied entry. Officials in California denied his citizenship because his parents were ineligible for naturalization under Chinese exclusionary policies. After Ark’s case was tried before the U.S. Supreme Court, the fourteenth amendment was upheld, granting Ark birthright citizenship as being a native-born citizen. Ark’s case was monumental and would serve as a precedent for birthright citizenship, regardless of race from that point onward.

Ozawa v. U.S. (1922)

In the year 1922, one Japanese man decided to challenge the legality of Asian immigrants being barred from the naturalization process and American definitions of race. Takao Ozawa sought to claim his rights and access to the American dream by attempting naturalization. Ozawa felt entitled to the right, mainly by the basis of his success, contributions to society, and efforts to Americanize. The most interesting argument was the color of his skin. It appeared “White” just like many other American citizens. Ozawa attempted assimilation much like Italians and Irish had in his recent past. He said, “I am not American, but at heart I am a true American.” However, the courts declared against him, and the country would not see Japanese immigrants achieve citizenship for many years after.

Thind v. U.S. (1923)

Bhagat Singh Thind was a high caste Indian man who arrived in America to attend university. He served in the U.S. army during WWI and attempted to obtain citizenship. His naturalization process was denied, on the basis of his “Hindu” status, despite the fact that he was Sikh. Thind sued, on the basis that he was, in fact, Caucasian. This logic follows the anthropological distinction that classified Thind as Caucasian, since his ancestors descended from the Caucus mountains. The court ruled against him, and his citizenship was revoked, along with other East Indians that had previously been granted citizenship.

As a result of this case, many other “non-White” persons lost their citizenship. One of those men was Vaishno Das Bagai. He escaped British tyranny in India and established a successful business in San Francisco. He received his citizenship in 1921, only later to have it revoked after the Thind ruling. Bagai took his own life in 1928 and his suicide note was published in the newspaper.

His words – “I came to America thinking, dreaming and hoping to make this land my home…But now they come to me and say, I am no longer an American citizen…Humility and insults, who is responsible for all this? Myself and the American government. I do not choose to live the life of an interned person: yes, I am in a free country and can move about where and when I wish inside the country. Is life worth living in a gilded cage?”

These three court cases prove that Asian Americans were continually denied a place in American society, despite military service, economic status, or willingness to adapt to society. This precedent continued into the later 20th century; even as American society diversified even further.