17 Addressing Intimate Partner Violence in the Northwest Territories, Canada: Findings and Implications from a Study on Northern Community Response (2011-2017)

Pertice Moffitt and Heather Fikowski

Death, posttraumatic stress, depression and other chronic physical conditions are reported outcomes of intimate partner violence (IPV) that contribute to the personal suffering of victims’ wellbeing and mental health and that of their families, and their communities. The Northwest Territories experiences IPV at a rate seven times higher than the national Canadian average. As well, homicides occurred every year of a recent study and were linked to domestic violence. It is apparent that IPV is problematic for individuals, families, and communities, and has a negative impact on the health of territorial residents. The purpose of this chapter is to share research findings from a five-year Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council-funded project about northern community response to IPV. From the grounded theory model, this chapter highlights the central phenomenon “our hands are tied” – frustration, and the normalization of violence has occurred. The implications are outlined in an action plan to guide future education, research and advocacy efforts.

Key Terms: Intimate partner violence, domestic violence, northern research, rural and remote, Northwest Territories, Canada

Introduction

The three territories of Canada have the highest rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) in the country (Statistics Canada, 2016). As well, the current Government of Northwest Territories (GNWT) 18th Legislative Assembly (2016) identified family violence as a key priority, which further establishes the weight of the problem in the lives of residents. Compounding the problem of family violence is the fact that of the 33 communities in the territory, 25 communities have populations of 1000 or less people. Remote communities, such as these, have few to no resources for women experiencing IPV. IPV is defined as a range of physically, sexually, and psychologically coercive and controlling acts used against an adult woman by a current or former male or female intimate partner (Elseberg & Heise, 2005). The purpose of this chapter is to share an overview of the research methodology, findings, and action plan from a Social Science and Humanities Research Council funded project about northern community response to IPV in the Northwest Territories (NWT). The findings establish that frontline workers’ “hands are tied” related to the intersection of many factors (for example, normalization of violence, depleted resources, a revolving frontline service, and historical trauma) which results in a crisis response to keep women safe. These are significant findings resulting in the creation of an action plan to move forward towards healing, healthy relationships and non-violent communities. This chapter will provide an overview of the findings as they relate specifically to the NWT.

Background

There is a dearth of research on IPV in Canada’s North. Mostly, what is known comes from incidents reported in local media and statistical reports related to criminal activity that is occurring. However, there is a beginning body of literature on IPV occurring in Canadian northern and remote areas (Faller et al., 2018; Moffitt & Fikowski, 2017; Moffitt, 2012; Wuerch, Zorn, Juschka & Hampton, 2016; Zorn et al., 2017), accounts of suicide at high rates in the Arctic (Kral, 2012; Isaacs, Keogh, Menard, & Hockin, 1998; Redvers et al., 2015), and unique contextual factors influencing the health and wellbeing of northerners (Bjerregarrd & Young, 2000). The effects of IPV are felt and interact at multiple levels, spanning the person, family, community, and territory. As reported by the Chief Coroner at a Domestic Homicide Prevention conference in London, Ontario, domestic violence is the causative factor in the majority of homicides in the NWT (Menard, 2017). A review of homicides in the NWT demonstrates that patterns of repeated incidents of violence are predictable indicators of homicidal risk and can provide frontline workers with opportunities to intercede (Rendall, 2016).

Methodology

This research spanned five years (2011 to 2016) and involved a multidisciplinary team from four jurisdictions (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the NWT.) In each jurisdiction, the research team consisted of community partners, academic researchers, and graduate and undergraduate students. In the NWT, our formal partner was the YWCA and we informally partnered with the Coalition Against Family Violence and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Domestic Violence Team. In all five years of the project, there was an annual meeting in Saskatchewan, led by Dr. Mary Hampton, the Principal Investigator; Joanne Dursel, the community partner; and Betty Mackenna, an Indigenous elder with academic and community representation from all four jurisdictions. A web-page was created and reports from all the research activity and knowledge mobilization are recorded (located at www2.uregina.ca/IPV/research).

The underpinning philosophical premises of this project were based on feminist perspectives of social justice (George & Stith, 2014; Moradi & Grzanka, 2017; van Wormer, 2009), inclusiveness, and equity in the research processes. Grounded theory and constant comparison process (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998) was used throughout the project.

There were 56 participants in total over the five years of this project. Participants were frontline workers currently employed in the NWT as RCMP, shelter workers, victim service workers, nurses, social workers, or counsellors. This mixed-methods study included an environmental scan of IPV resources, synthesis of media reports, gathering RCMP reported incidents, and Geographical Information Systems (GIS) mapping. Semi-structured interviews (n=31) were completed in the third year, which helped to formulate a preliminary model to describe the community response to IPV. In the fourth year, narrative inquiry of two northern communities using focus groups (n=2) and semi-structured interviews (n=11) further developed and confirmed the model. Finally, an action plan was developed and an extensive knowledge mobilization plan was implemented whereby we returned to seven communities in the NWT as well as Whitehorse, Yukon and Iqaluit Nunavut to report the findings

Findings

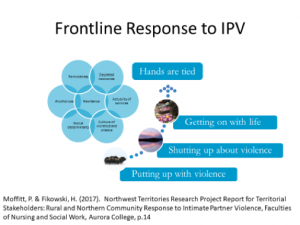

The findings from this five-year study include three tools to help navigate IPV in the territory. First of all, we completed five GIS maps from an environmental scan and statistics of reported IPV incidents, homicides, Emergency Protection Orders (EPOs), as well as the effects of summer and winter seasons on travel distances to the major center of NWT if one were escaping violence. These GIS maps provide foundational pictures of the needs and gaps in resources and the extent of the IPV occurrence across the NWT. Secondly, we created a grounded theory with the central problem of “our hands are tied” that explains the community response to IPV through three social processes: shutting up about violence, putting up with violence, and getting on with life. The model helps to understand the challenges and barriers for women experiencing IPV and for frontline workers who are trying to meet the needs of women. Thirdly, we developed an action plan that identifies strategies and directions for decision makers and policy planners in the NWT to transform the community response to IPV from a crisis management response to a coordinated effort that produces a reduction in the rates of violence and leads to healthy outcomes.

The central phenomenon within community response to IPV is the frustration by frontline service providers managing a multitude of factors, including limited resources; turnover of frontline workers; no institutional memory; repeated offenders of violence; increased homicides and suicides related to violence; a history of colonization; silence and secrecy; and blame and shame, that has been stated as “our hands are tied.” The following social processes are embedded in the community response model, “our hands are tied” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Our Hands are Tied Model

Putting Up with Violence

Indigenous communities are experiencing higher rates of IPV (Statistics Canada, 2016) and most of the remote communities in the NWT are Indigenous. As a victim service worker shared, “…a lot of women do not come forward. They just live in fear and they will not leave their partner because of the threat [reprisal, retribution] it is too dangerous.” One police officer said “they [the victims] can’t handle the pressure from the family members and the community to stay in that relationship. They have nowhere else to go. So basically there is no way out for victims who are chronically abused.” This suggests an attitude of acceptance that comes perhaps from shame and blame leading to a sense of futility in pursuing justice for the victim and an acceptance that violence is a “way of life.”

There is shaming of victim- it is her fault. The biggest take home is that there is no way out and they are criticized by children and families. They lose everything if they leave. The man is controlling the house. She can’t afford to go. One woman left for a couple of years and everyone talks and criticizes. Women lose their children and they feel this is too steep a price to pay. It is a very untenable solution for many women (Shelter Worker).

The social determinants of health and, in particular, housing, are an issue for women fleeing violence. One participant said “housing and homelessness are a big barrier. It’s so expensive and difficult to live up here…even if it is traumatic and violent, chances are you will stay because housing is so precarious and expensive” (Police Officer). The remoteness of many communities in the NWT contributes to putting up with violence.

Shutting Up About Violence

There is a culture of violence and silence in the territory that makes acts of IPV insular, protected, and private. The factors related to shutting up about violence are historical trauma, normalized violence, gossip, community retribution, family and community values, and women’s self-preservation. As one participant shared, “I think that the impact of residential school is a major divider and a cause of a really prevalent lack of trust that permeates our culture.” (Shelter Worker). Another participant said, “I think with the heritage with residential schools and people suffering traumatic injury there and that pain being handed down generationally, I think there’s been generations of people putting up with a lot…” This culture of violence and silence contributes to sustaining turmoil that surrounds victims of violence and, in turn, influences frontline workers’ efforts to help by creating a barrier of disengagement with the formal support system.

Getting On With Life

Frontline workers describe the context and multiple barriers faced in their efforts but they also described women as strong and resilient. Survivors of IPV demonstrate creative solutions in keeping their children and themselves safe through personal safety planning and ways of being with the perpetrator to help diminish an escalating situation. They are resisting acts of violence and taking measures to keep their children safe by protecting them in situations that are traumatic and sometimes life-threatening. As a victim service worker noted “some women are such strong fighters, they’re like okay I am going to figure this out [in regards to getting help]”. Another frontline worker said in their positions it is important to recognize

They’ve lived here for tens of thousands of years, and if we can support the healthy in

that network, I think that’s what’s going to make the change cause it’s not us from the outside coming in, it’s recognizing and valuing and supporting the strength that is already there.

A nurse described the sense of empowerment she has heard women describe when they are finally able to leave an abusive relationship:

I’ve met with some women who were in really bad way who did finally make it. They’re so proud of themselves that they actually managed to get out of the relationship and they’re happy, they feel good not having been beaten up. Some of them, I find, some of the Aboriginal ladies really find the Healing Drum very useful and they go there… They say it’s the spirituality and they say it’s other people understand because they’ve been through the same thing. So it’s the support group from people who they said ‘they help you stay strong and not to go back’.

The sense of hope and optimism participants shared about women surviving abuse in the NWT also described women’s strength and perseverance. This perspective carries weight in providing counter-measures to the impacts of their frontline work in the remote northern setting of the NWT which allows them to get on with life as well.

Implications and Action Plan

The model, “our hands are tied”, describes a northern community response to IPV. The model explicates struggle and pain that within the timeframe of this study included several homicides in the NWT. Yet, the resiliency of women experiencing IPV is also embedded in the model speaking to hope for a future where nonviolence and harmony can exist in communities. Many factors contribute to violence and were considered as we developed an action plan for the territory. The plan is derived from participants in the study responding to the question “how do we create and sustain nonviolent communities?”, as well as considering and integrating published literature of best practices relevant for the territorial context. The NWT action plan consists of the following seven strategies: knowledge mobilization, education and awareness, stable and adequate funding, a coordinated response strategy, assessment and screening, social supports, and community healing. In this section, we will briefly address each strategy.

Knowledge Mobilization

Through a process of community meetings across the territory in 2017, the research and action plan were communicated to local service providers along with government planners and policy makers. At one meeting a frontline worker shared “we are a like a canoe that’s running in the wrong direction of the river, getting nowhere, no matter how hard we are paddling.” By targeting the actions in this plan, propelling the plan will take us upriver with solutions to create places less violent.

Education and Awareness

Recruitment and retention of service providers is an ongoing concern and because of the reality of frequent turnover, a frontline worker said there is no institutional memory of incidents, responses, policies and procedures in the NWT across agencies. This means that orientation, professional development, and training must be regularly implemented to maintain effective responses locally. Ideally, local people should drive the strategy so that it is created at home and is culturally and contextually intuitive. The legacy of a history of colonization, with its impact on territorial peoples and unique knowledges of communities, needs to be shared with the frontline service so that cultural safety and reconciliation is inherent in each action.

Many participants in this study expressed the necessity of emergency safety planning for women and children. A police officer shared that conflict occurs everywhere and when it happens, service providers need to be prepared to deal with the immediate situation of violence to keep women and children safe:

…I think the issue is having proper supports and education of people on the ground, on the scene so they can give the person who’s making the report or having the issue sort of the immediate intervention, because if they’re going to accept any kind of help or intervention, it’s going to be in the immediate time after something happens…

Similarly, women who experience violence need to know how to develop a personal safety plan and how to access an emergency protection order when needed. These plans should be tailored to women’s choice, staying strategies or leaving strategies, all of which must consider the risks in fleeing, realities of staying, and barriers women experience with either choice.

Stable and Adequate Funding

The complexity of issues related to IPV and barriers that women face (isolation, housing, financial uncertainties, loss of children, and more) shape their decisions to stay or leave a violent relationship. Because of this, women living in northern and remote areas use a variety of strategies when faced with IPV based on their context (Riddell, Ford-Gilboe & Leipert, 2008). Long-term funding targeting social determinants of health (such as housing, employment, education) will improve the livelihood of women experiencing IPV.

Coordinated Response to Violence

Coordinated community response has been defined as a unified response to domestic violence with the creation of a council or agency consisting of community services, such as police, government workers, shelter workers, social services workers, and other stakeholders to respond in a coordinated way to violence in communities (Shorey, Tiron & Stuart, 2014). In the NWT, interagency meetings happen sporadically but if they were stabilized with local people and regular meetings they may foster more coordinated responses. Enhanced advocacy, collaboration and coordination required to meet the needs of victims experiencing IPV may be realized. Using a case management and interprofessional approach could become a reality and may improve the response to IPV in remote areas and streamline access to supports.

Assessment and Screening

Screening tools for intimate partner violence (Arkins, Begley & Higgins, 2016) are needed to assess risk and provide interventions. An assessment question such as (does he hit you, does he hurt you?) could be used in the Well Women programs in remote communities. Practitioners will require education in how to respond to affirmative answers to these questions and how to refer or counsel women. Already, there is an assessment section on the prenatal tool but it is inconsistently used because of turnover, discomfort with asking this sensitive question and lack of knowledge of resources available.

Death reviews are recommended as a way of studying the circumstances leading up to homicides, identifying key predictors of risk for victims, creating decision making tools for risk assessment and safety planning, and developing preventative actions for service providers counselling victims of violence. There is not a formal death review committee in the territory.

Social Supports

Almost all participants spoke about the importance of early education with children and teens, recognizing the number of children being exposed to IPV in their family homes. Recommendations were made to include formal and informal education strategies, and promotional materials, and highlighting community champions living violence-free lives. The focus of education, be it formal or when engaged with frontline providers in a preventative service, would help children and youth to develop healthy relationships and effective coping strategies to manage an overall sense of healthy wellbeing.

Some RCMP suggested “dry communities” (where alcohol use is banned) as an intervention. The regulation of alcohol in such a manner is a community-driven initiative in the NWT (Davison et al., 2011). In addition, there is a need to intervene with bootleggers who are bringing in vast quantities of alcohol, distributing it without censorship. One suggestion to combat the bootlegging problem was to make it more difficult for people to purchase large orders of alcohol through policy changes at the liquor store outlets.

Community Healing

“Reclaiming our Spirits”, a health promotion intervention, holds promise for Indigenous women experiencing intimate partner violence (Varcoe et al., 2017). Although this is an urban intervention, it may be adapted and used with women living in northern and remote areas.

Land-based healing (Redvers, 2016) is gaining attention as a means to enhance wellness in the territory. An Arctic Indigenous Wellness Project (CBC, 2018) is currently being implemented with Indigenous Elders in Yellowknife, recipients of the Arctic Inspiration Award. Participants suggest that alcohol is a factor in IPV and addictions are a major problem requiring local healing. Land and place hold special meaning and relationship to Indigenous northerners’ well-being and are now being accessed with hopes of sustained wellness.

Conclusion

IPV is on the radar of frontline service providers, government officials, community advocates and researchers alike. This study generates new knowledge about the experiences of service providers working with women who are faced with violence in the NWT and action plan to address ways to move towards nonviolence. We are building a research agenda to further these findings. Research is already being conducted specifically in relation to “keeping families safe: emergency protection orders” to better understand the nature of EPOs accessed by women in violent emergencies, the outcomes to those IPV emergencies and the utility for its applicants (the women). We are also collaborators in a national study on domestic homicide prevention (CDHPI, n.d.) and partners on a national observatory for femicide (CFOJA, 2018). With a proactive approach and collaboration with our communities, researchers, and decision makers, we hope to untie the multiplicity of factors that feed into the prevalence, severity and frequency of IPV across the NWT.

Additional Resources

Rural and Northern Response to Intimate Partner Violence

http://www2.uregina.ca/ipv/index.html

This offers a localized space to obtain the details of the research project from which this chapter was based. It provides information about the project’s background, final reports from all four jurisdictions in Canada (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories), as well as knowledge translation activities in the last several years.

Aurora Research Institute/Aurora College

http://nwtresearch.com/research-projects/health/intimate-partner-violence

This site offers a copy of the report by Moffitt and Fikowski (2017) on “Rural and Northern Community Response to Intimate Partner Violence.”

Family Violence Initiative

Organized and led by the Public Health Agency of Canada, this initiative serves as a collaboration with multiple government departments and agencies to address family violence. The website includes information about family violence, trauma-informed approaches to policy and practice resources, ways in which professionals can promote healthy, safe relationships, tools for professionals working with people and communities affected by family violence, and links to possible funding opportunities.

National Aboriginal Circle Against Family Violence

This organization focuses on supporting shelters in their efforts to promote safe environments for Indigenous Canadian families. It offers program initiatives for shelter and transition houses that are culturally appropriate as well as networking opportunities for frontline workers, especially those who are in remote locations. It also works to improve public awareness about family violence in Indigenous communities as well as strengthening the relationship and securing funds between all levels of governments, non-governmental organizations and Indigenous partners.

National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health

https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/en/

This Canadian national organization supports Indigenous health through research, policy, and practice initiatives. Information includes family health across the lifespan and social determinants that impact Indigenous family health. It also includes a two-part series report on historic trauma, explaining Indigenous peoples’ experiences of trauma and oppression as cumulative and intergenerational.

Status of Women Canada

http://www.swc-cfc.gc.ca/index-en.html

The Status of Women Canada aims to promote women’s full participation in Canadian society. Part of their efforts work to end violence against women and girls. It does this by providing policy directives, supporting women’s programs, and promoting women’s rights.

Books

DeRiviere, L. (2014). The healing journey: intimate partner abuse and its implications in the labour marker. Winnipeg, CA: Fernwood Publishing.

References

Arkins, B., Begley, C., & Higgins, a. (2016). Measures for screening for intimate

partner violence: a systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 23(3/4), 217-235.

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). (2018). What will the Arctic Indigenous Wellness Project do with $1M. Arctic Inspiration prize? Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/2018-arctic-inspiration-prize-1.4513445

Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative (n.d.). Retrieved from http://cdhpi.ca/

Canadian Femocide Observatory for Justice and Accountability. (2018). Retrieved from https://femicideincanada.ca/home/contact

Davison, C.M., Ford, C.S., Peters, P.A., & Hawe, P. (2011). Community –driven alcohol policy in Canada’s northern territories 1970-2008. Health Policy, 102, 34-40.

Elseberg, M., & Heise, L. (2005). Researching violence against women: practical guidelines for researchers and activists. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Faller, N., Wuerch, M.A., Hampton, M.R., Barton, S., Fraelich, C., Juscka, D., Milford, K., Moffitt, P., Ursel, J., & Zederayka, A. (2018). A web of disenheartenment wuth hope on the horizon: intimate partner violence in rural and northern communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi:10.1177/0886260518789141

Glaser, B.G., & Strauss, A. (1967). Discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Isaacs, S., Keogh, S., Menard, C., & Hockin, J. (1998). Suicide in the Northwest Territories: A descriptive review. Chronic Diseases in Canada, Ottawa, 19(4), 152-156.

Kral, M.J. (2012). Postcolonial suicide among Inuit in Arctic Canada. Cultural Medical Psychiatry, 36, 306-325.

Moffitt, P., Fikowski, H., Mauricio, M., & Mackenzie, A. (2013). Intimate partner violencein the Canadian territorial north: perspectives from a literature review and a media watch. InternationalJournalofCircumpolarHealth,S72:21209.Retrievedfrom http://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21209

Moffitt, P., & Fikowski, H. (2017). Northwest Territories research project report for territorial stakeholders: rural and northern community response to intimate partner violence. Yellowknife: Faculties of Nursing and Social Work, Aurora College

Redvers, J. (2016). Land based practice for Indigenous health and wellness in Yukon, Nunavut and the Northwest Territories. Doctoral thesis. University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Redvers, J., Bjerregaard, P., Eriksen, H., Fanim, S., Healey, G., Hiratsuka, V., Jong, M., Larsen, C.V.L., Linton, J., Pollock, N., Silviken, A., Stoor, P., & Chatwood, S. (2015). A scoping review of Indigenous suicide prevention in Circumpolar regions. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 74(1) 27509. doi:10.3402/ijch.v74.27509

Rendell, M. (2016). Domestic violence involved in the vast majority of NWT homicides. CBC News North. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/domestic- violence-involved-in-vast-majority-of-nwt-homicides-1.3879679

Shorey, R.C., Tiron, V., & Stuart,G.L. (2014). Coordinated community response components for victims of intimate partner violence: a review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 19(4), 363-371. Doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.06.001

Statistics Canada (2016, January 21). Family violence in Canada: a statistical profile, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub85-002-x/2016001/articel/14303-eng.htm.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newberry Park: Sage.

Varcoe, C., Browne, A.J., Ford-Gilboe, M., Dion Stout, M., McKenzie, H., Price, R., Bungay, V…Merritt-Gray, M. (2017). Reclaiming our spirits: development and pilot testing of a health promotion intervention for Indigenous women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Research in Nursing & Health, 40, 237-254. doi: 10.1002/nur.21795.

Wuerch, M.A., Zorn, K.G., Juschka, D., & Hampton, M.R. (2016). Responding to intimate partner violence: challenges faces among service providers in northern communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1-21, doi:10.1197/0886260516645573

Zorn, K.E., Wuerch, M.A., Faller, N., & Hampton, M.R. (2017). Perspectives in regional differences and intimate partner violence in Canada: a qualitative examination. Journal of Family Violence, 32, 633-644. doi: 10.1077/s.10896-017-9911-x