7 Ghosts In Stereo: Manifest Stations

Steve Stelling

|

|

My background and creative interests have centred around drawing and painting, and in recent years I’ve started making my own stereo equipment. I sometimes imagine it as a hobby—a break from the long-running, self-conscious motives that guide my visual art. Regardless, my recent interest in do-it-yourself audio gear sends me down a number of reflective cul-de-sacs that give my pastimes a dimension to listening that I’d like share.

|

Listening: I notice that I listen a number of different ways; it all depends on what I’m hearing. When I am listening to someone speaking, I try to pay attention so I can understand the thoughts they are trying to convey. When I listen to my surroundings, I listen for sounds that provide a signal or sign of something to take note of, like the approach of a car, applause, water. And then there is music. With music, I notice that I’m listening to sound itself. Sound as an invisible presence: real, but often deceptive, consuming, and ephemeral. Music, to me, is sound-as-presence that blooms and fills a space, a sentiment I’ll return to.

|

|

| Drawings by Steve Stelling, Graphite on paper. Licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) Licence. | |

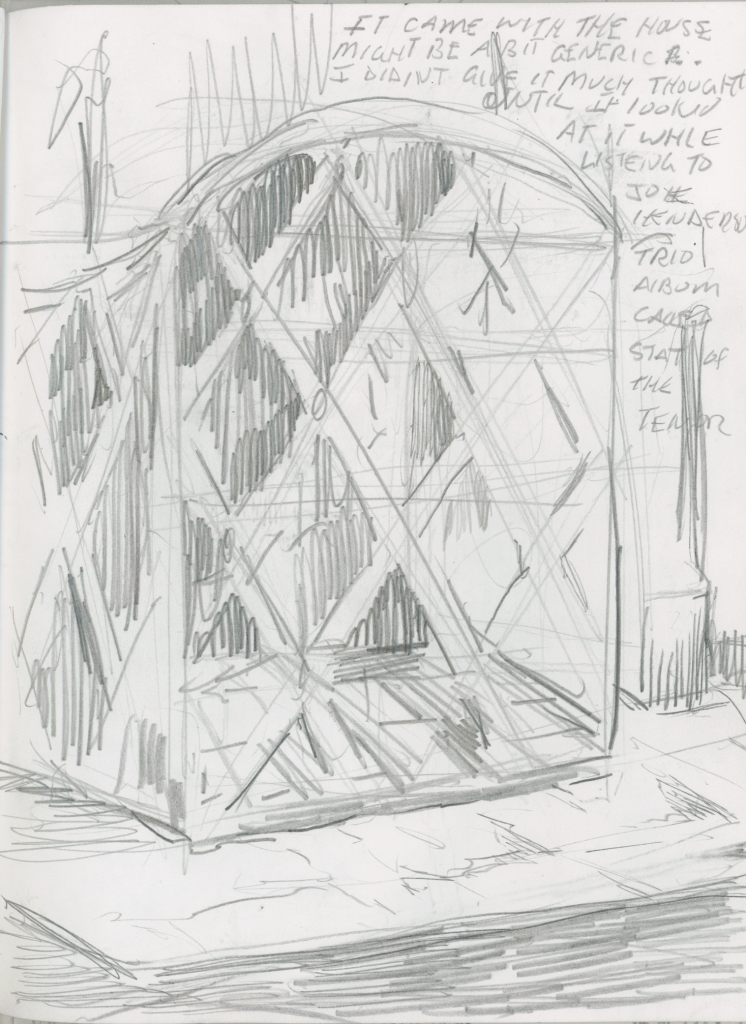

Hoolographic glow: A few years ago, I got really excited when listening to a recording of a jazz trio: it seemed to be coming out of our fireplace! The illusion was so real, it nearly knocked me out of my chair. This pair of drawings are notes about the experience. Specifically, it was Ron Carter’s bass coming from the depths of the fireplace. Carter and Al Foster, whose drums were a bit more forward, near the mantle’s left supporting column, were the rhythm section backing Joe Henderson on his live album State of the Tenor.

|

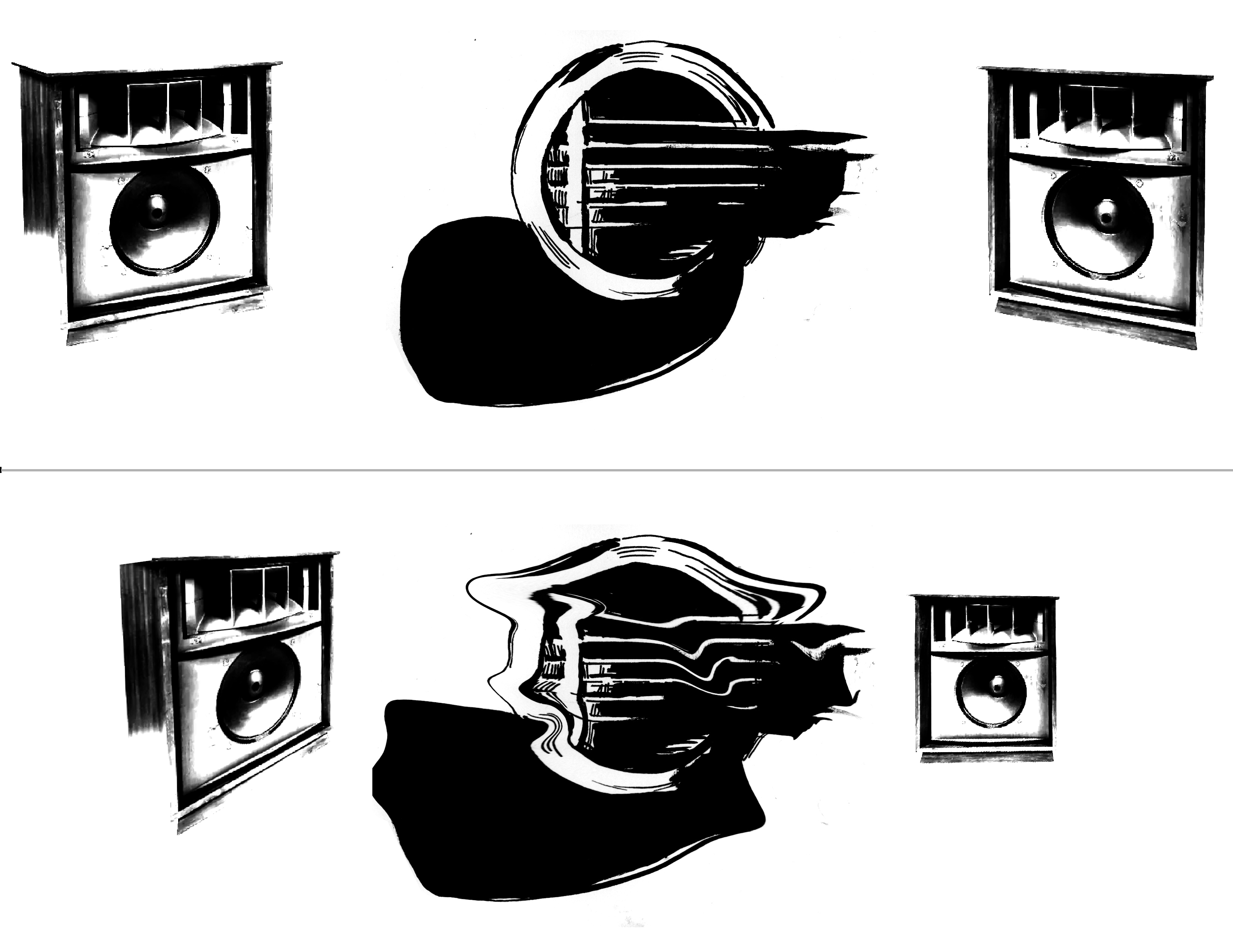

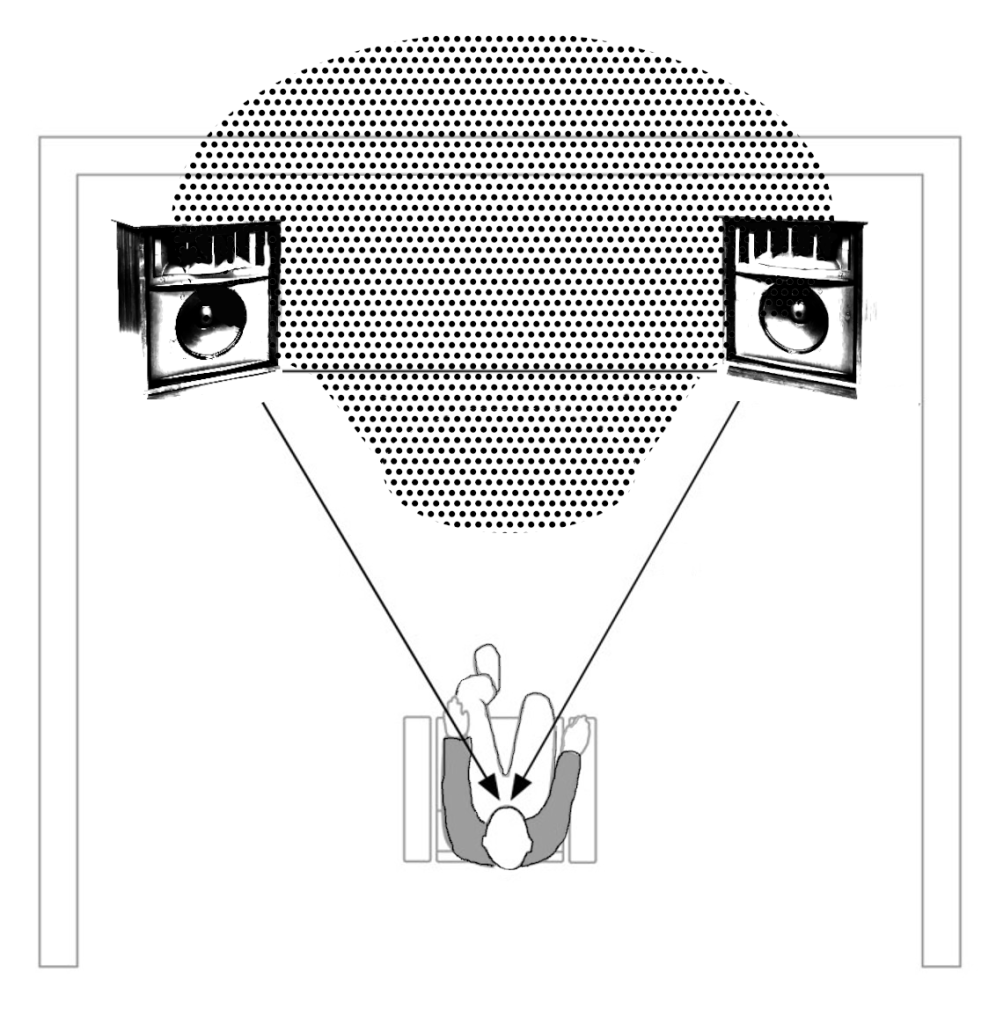

What you see here is a diagram showing (roughly) how to station oneself relative to two speakers. Following the advice of members on an audio message board, I made adjustments to the placement of my own speakers. Setting them up “just so.” When positioned with deliberate attention to distance and angle, the sound from the left and right speakers cohere as a dimensional cloud or ball of sound, suspended in a field between the speakers, recognized as the “soundstage” among initiates. Instruments seem to come not just from an array of locations between the speakers but extend past them, in front of them, and from behind the speakers, even deep into space on some recordings. This explains how Ron Carter seemed to be playing in my fireplace.

|

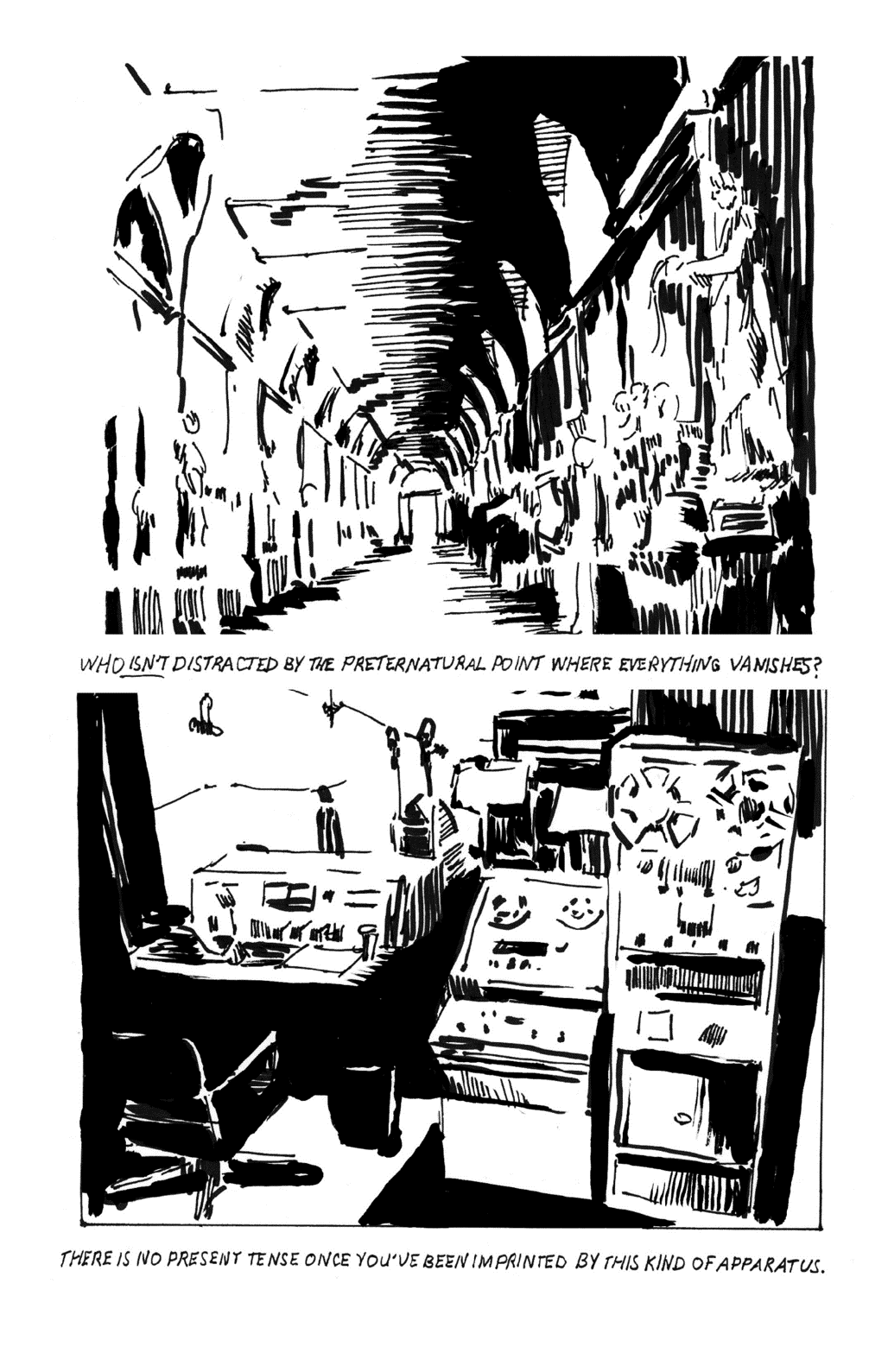

Some recordings, when played with a well-matched combination of speakers and amplifiers, can conjure an alarmingly illusionistic soundstage: the dimensional cloud or ball of sound has what feels like protrusions and recessed areas of its own, with some instruments and voices coming forward and others anchored in back. This is a drawing I made years ago; it was made to suggest a sort of cityscape. Just recently, my first real experience of stereo imaging brought it to mind. I knew I liked decent sound, and I liked it when things were evenly balanced, but I never tried to set up equipment so as to conjure anything magical from my music.

|

Like most people, I’ve encountered audible illusions before. Most often these are incidental: like mistaking one sound for another. Occasionally, however, I’ve encountered illusions that were the result of deliberate engineering—engineering that offers a surprise one might expect from magic—like the whispering arch of Hays Hall on the Ohio State University campus. Here, one can whisper in the quietest voice into the left leg of the arch, and a partner can hear it with perfect clarity fifteen -feet away if they put their ear to the right leg of the arch. What was new about this night in my living room is that it was the first time I’d encountered a work of art manifesting itself with such substance in my own home.

|

It didn’t feel like “I was there” at the venue hearing the band play. And it wasn’t like I had the actual musicians right in front of me either. What felt real and palpable was the “recorded-ness” of the music. The recording was so present.

This is a drawing made from ink and layers of cut paper. Perhaps you can recognize a fragment of a curved staircase and maybe some other forms suggestive of architecture. Like the musicians and instruments on a recording played in one’s home, the depicted volumes and spaces aren’t exactly present, but the drawn-ness and papery paintedness of the work very much is.

It was analogous to the feeling I get standing in front of this Mark Rothko painting, Untitled (Purple, White, and Red), in the Art Institute of Chicago, where I feel the colour’s pulse is slowly breathing at me.

|

This is a snapshot of speakers I considered buying. I passed on them, but I love how the cabinets of these old Pioneers from the mid-1970s resemble our fireplace grate. They’re what came to mind as I’d stared at the fireplace, transfixed by the illusion of sound radiating from a shallow concave space behind a screen, as though the fireplace was one giant speaker.

Grumps to gramps are punks to amps: Following online audio discussions eventually led me to understand that attention to equipment plays a big role in obtaining the kind of sound I was so impressed with. It also became clear that learning to make my own equipment could be considerably cheaper than buying high-end boutique gear.

|

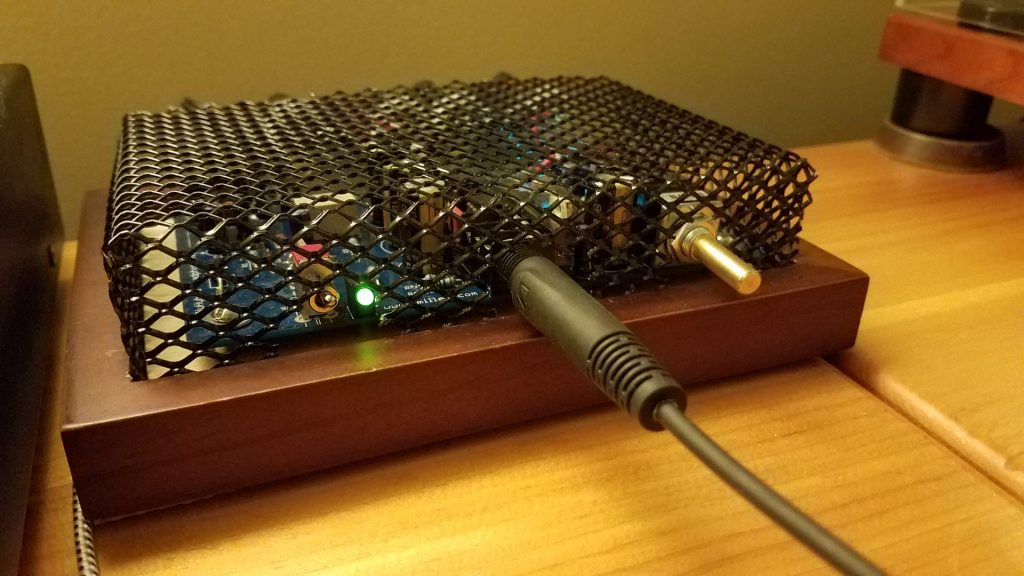

So I made a little headphone amplifier for starters.

|

Building that little amp, the tools it required, and the smell of melting solder brought me back to this space. This is the only setting in which I can imagine my dad being an active and engaged guy. It is the basement workshop in my childhood home, as it looked immediately after my parents moved out.

My dad was the most reticent and reclusive person I’ve ever known; those traits grew more entrenched the longer I knew him. By my adulthood, our relationship was more or less reduced to exchanging rote pleasantries and not much more. Despite him being around until only a few years ago, my memories of him are exclusively from when I was a kid and he was busy making stuff: home carpentry and some electrical work.

|

|

|

| Photos by Steve, licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) Licence. | ||

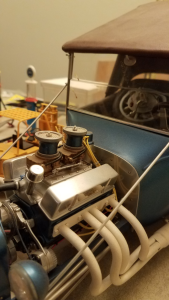

For sheer enjoyment he was mostly focused on building scale-model cars. He was a fastidious craftsman in this regard. He would begin with off-the-shelf kits from Revell or Monogram as foundations, modding them by fashioning numerous custom pieces from wire, aluminum plate, and brass tubing.

|

|

| Photos by Steve, licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) Licence. | |

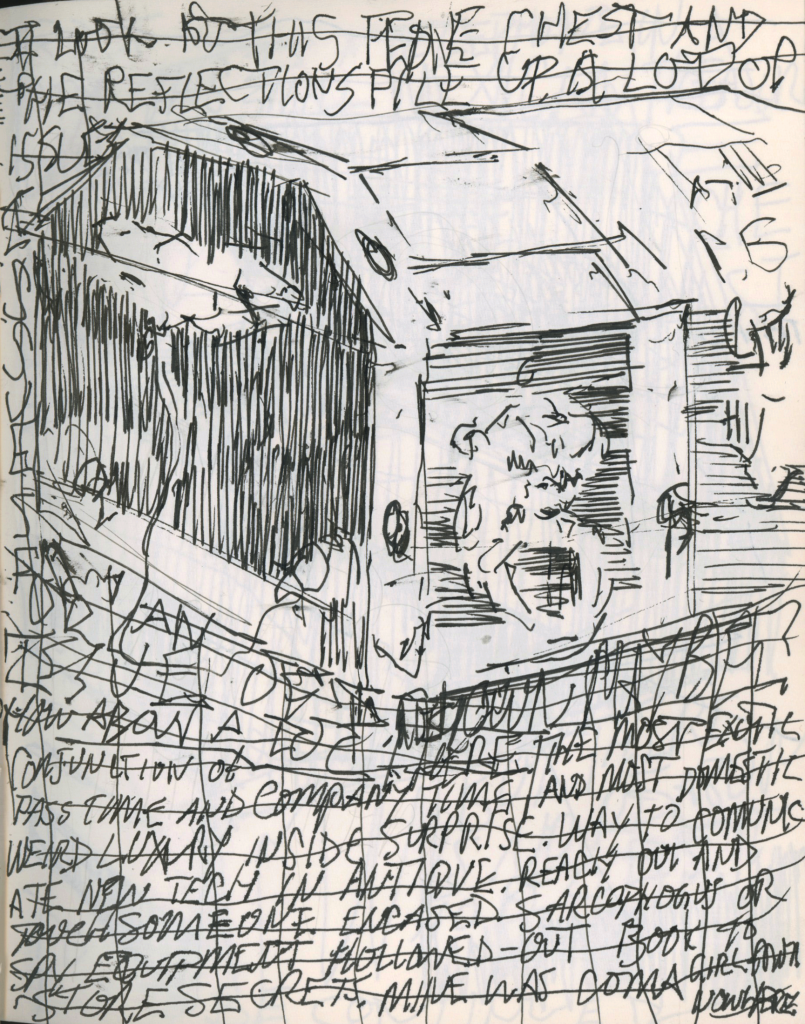

Also, there was never a shortage of downright weird projects. For example, this decorative chest whose interior he upholstered and converted to house a telephone. We had more hard-wired telephones in our home than anyone I’d ever known, mostly because he worked for the local phone company (maintaining analog switching stations and cable splicing outdoor and underground lines). Considering how uncommunicative he was, his life spent among phones has always been a crown jewel of irony.

|

This is the second amplifier that I built. Audiokarma.org and diyaudio.com are online message board communities where members share circuit designs, schematics, parts lists, operating specs, and so on (some even link to personal online stores where members sell their own printed circuit boards). It was by reading and querying fellow members that I learned how to build my first full-scale tube amplifier.

|

Why I wanted a tube amp was because the ones I had heard all made the sound feel “fleshed out” or gave it “body.” The sound blooms and spreads in a way that has greater presence without being louder.

And, in this photo we see my amplifier cooking electrons in little glass vacuums. It is literally roasting negativity to produce sound.

Those kinds of tricks (lived contradictions?) are so rich in metaphor that these audio projects promote the kind of reverie that bleeds into my practice as a visual artist.

|

|

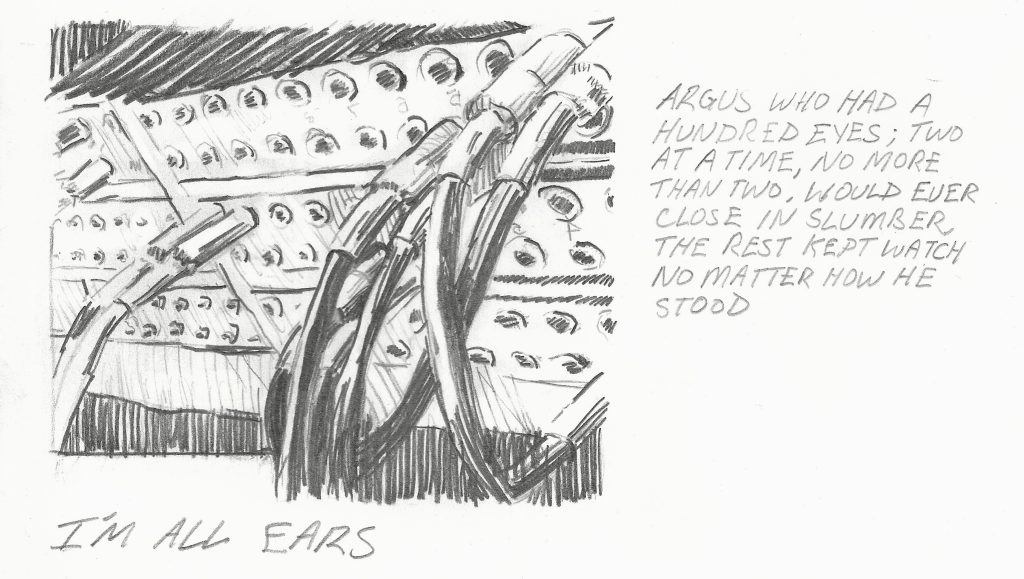

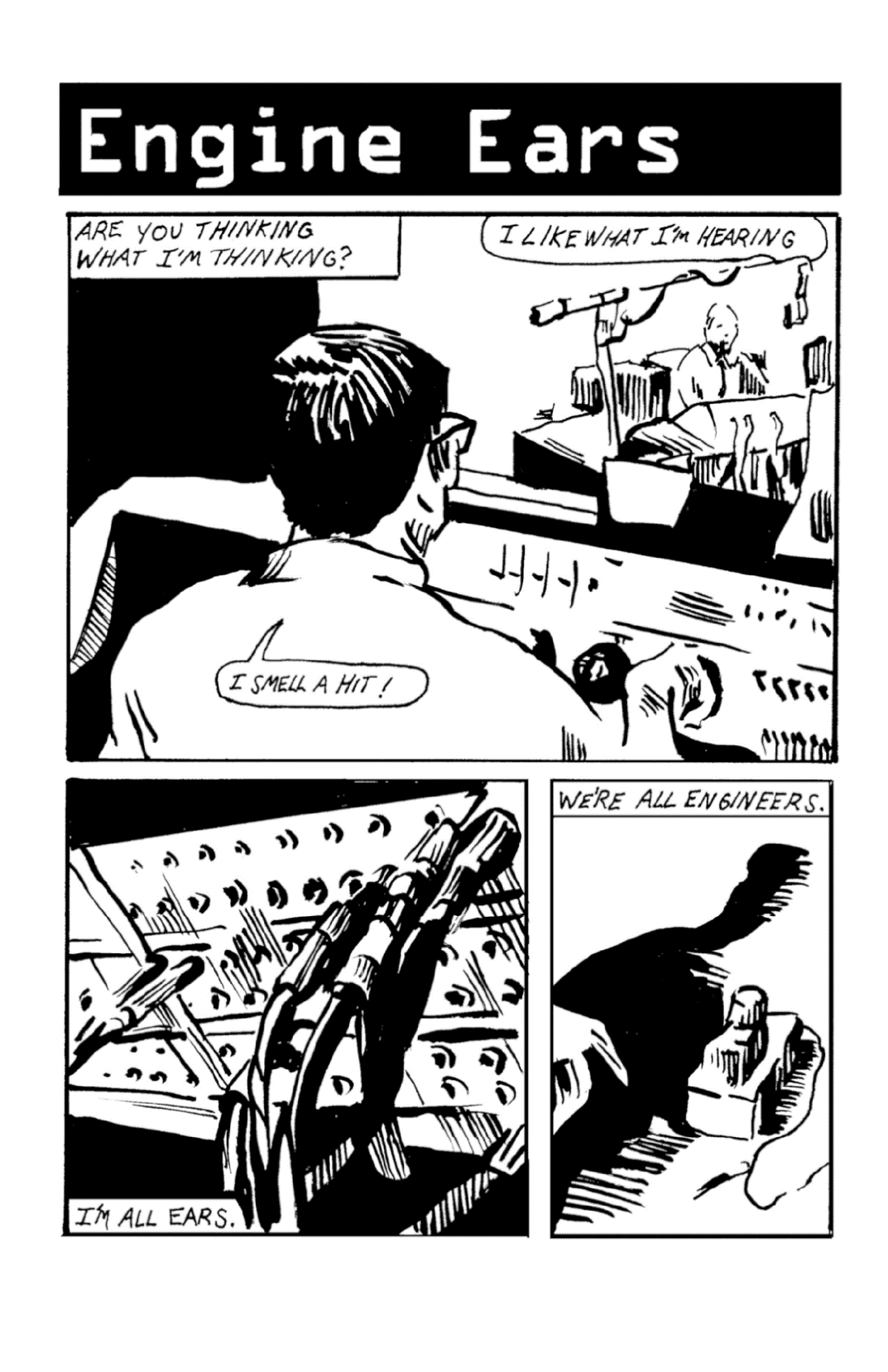

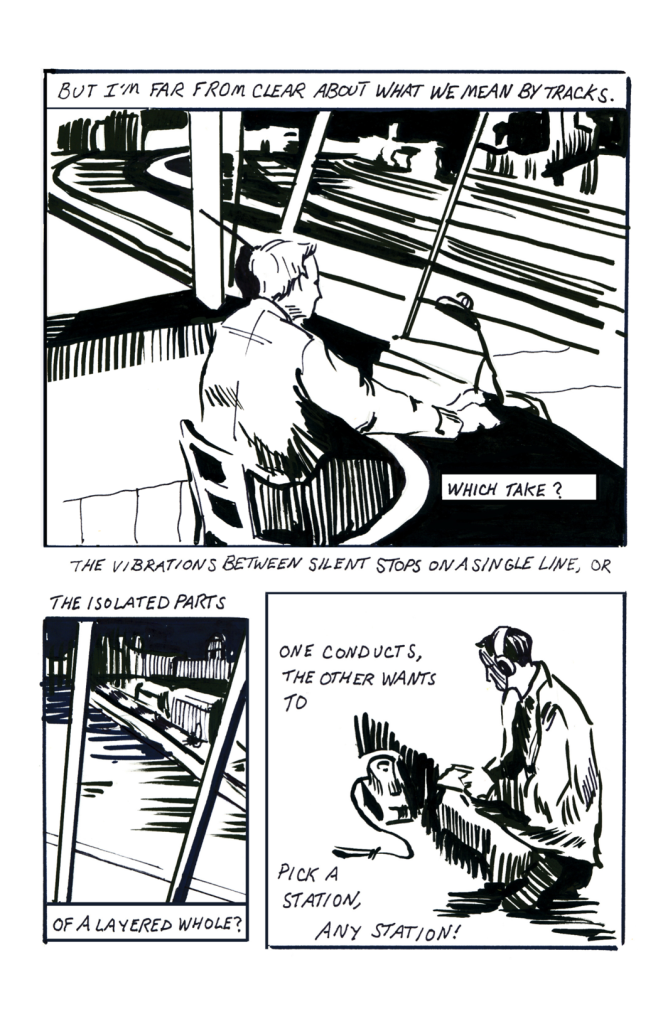

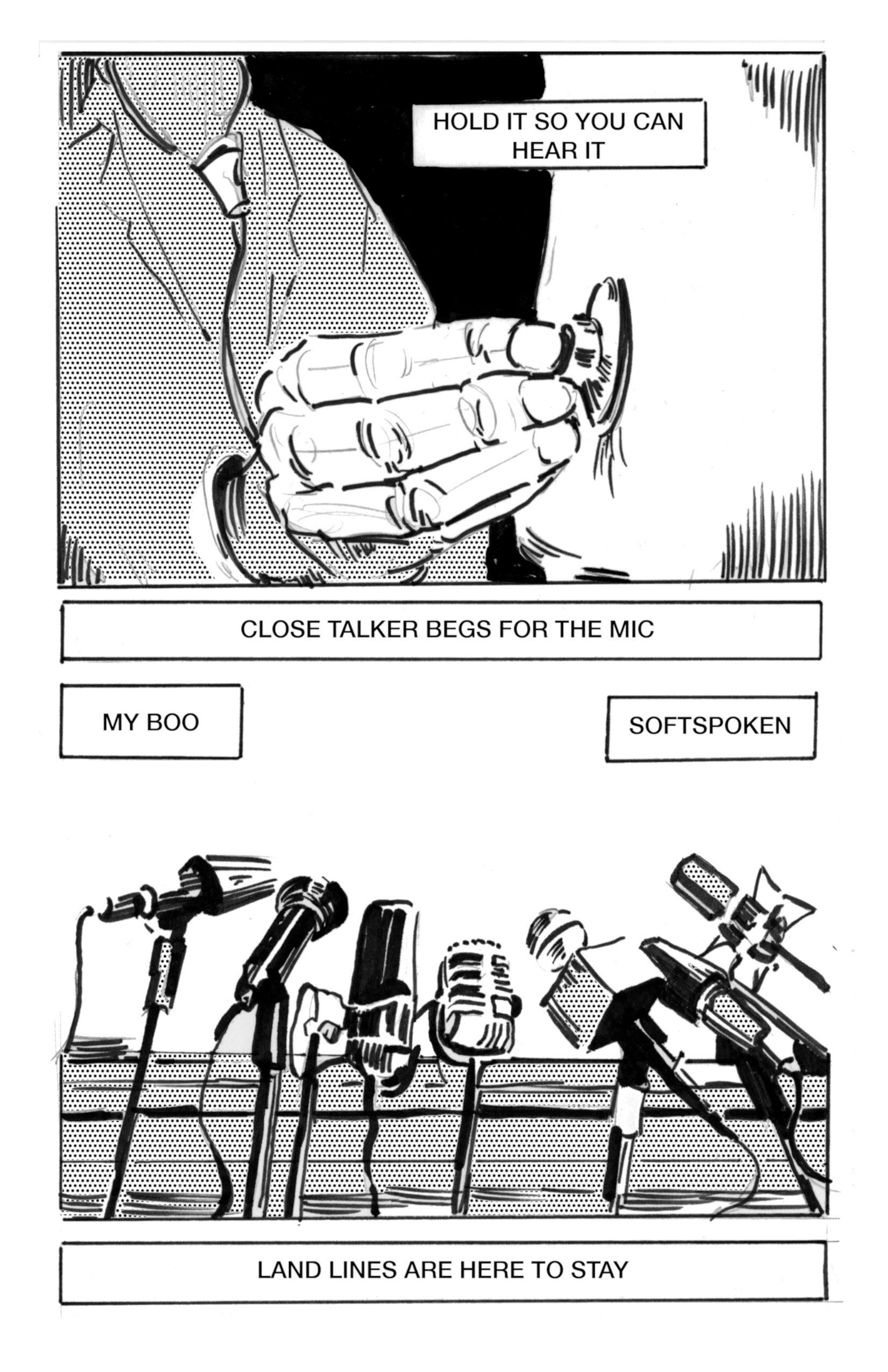

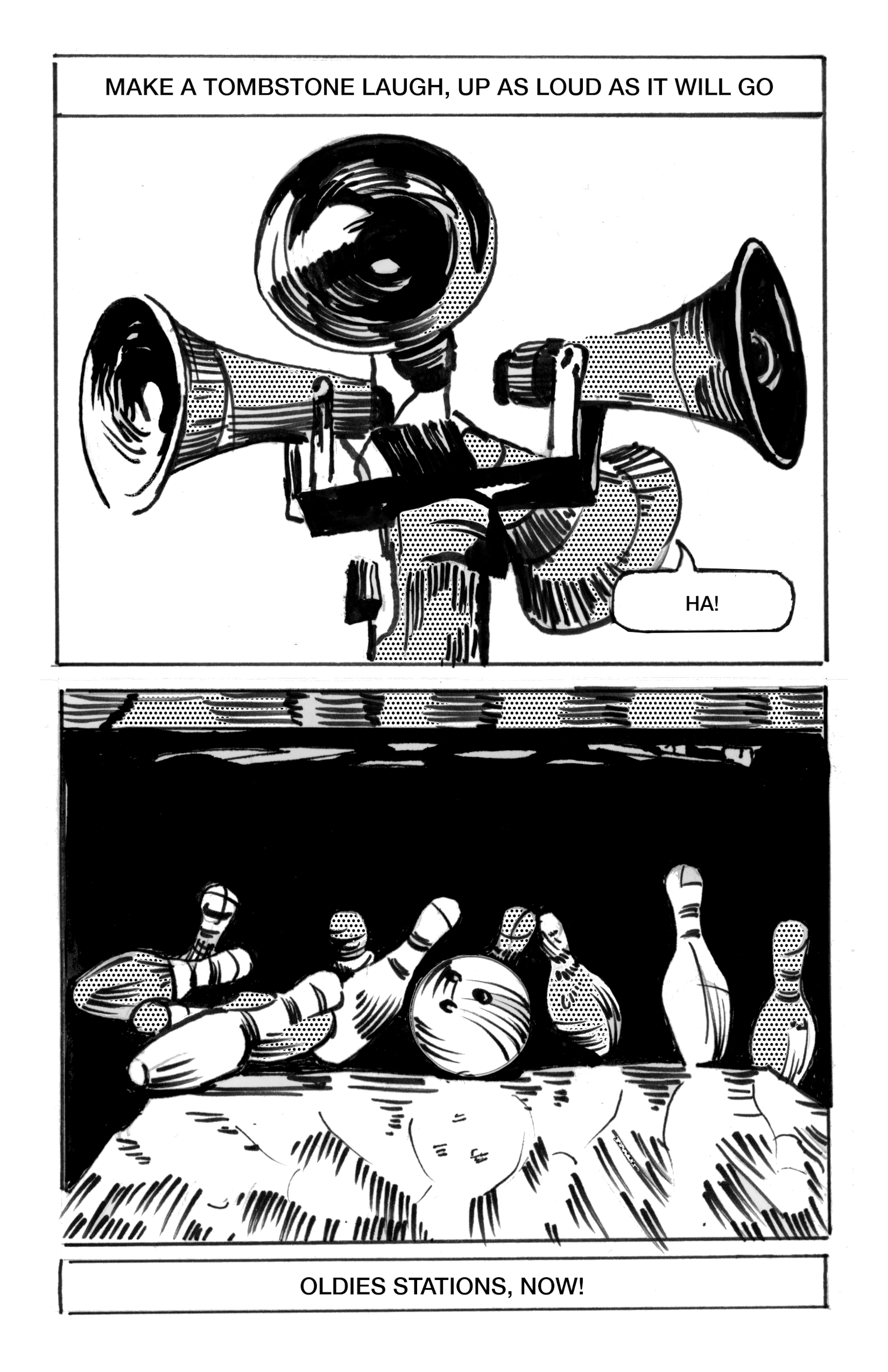

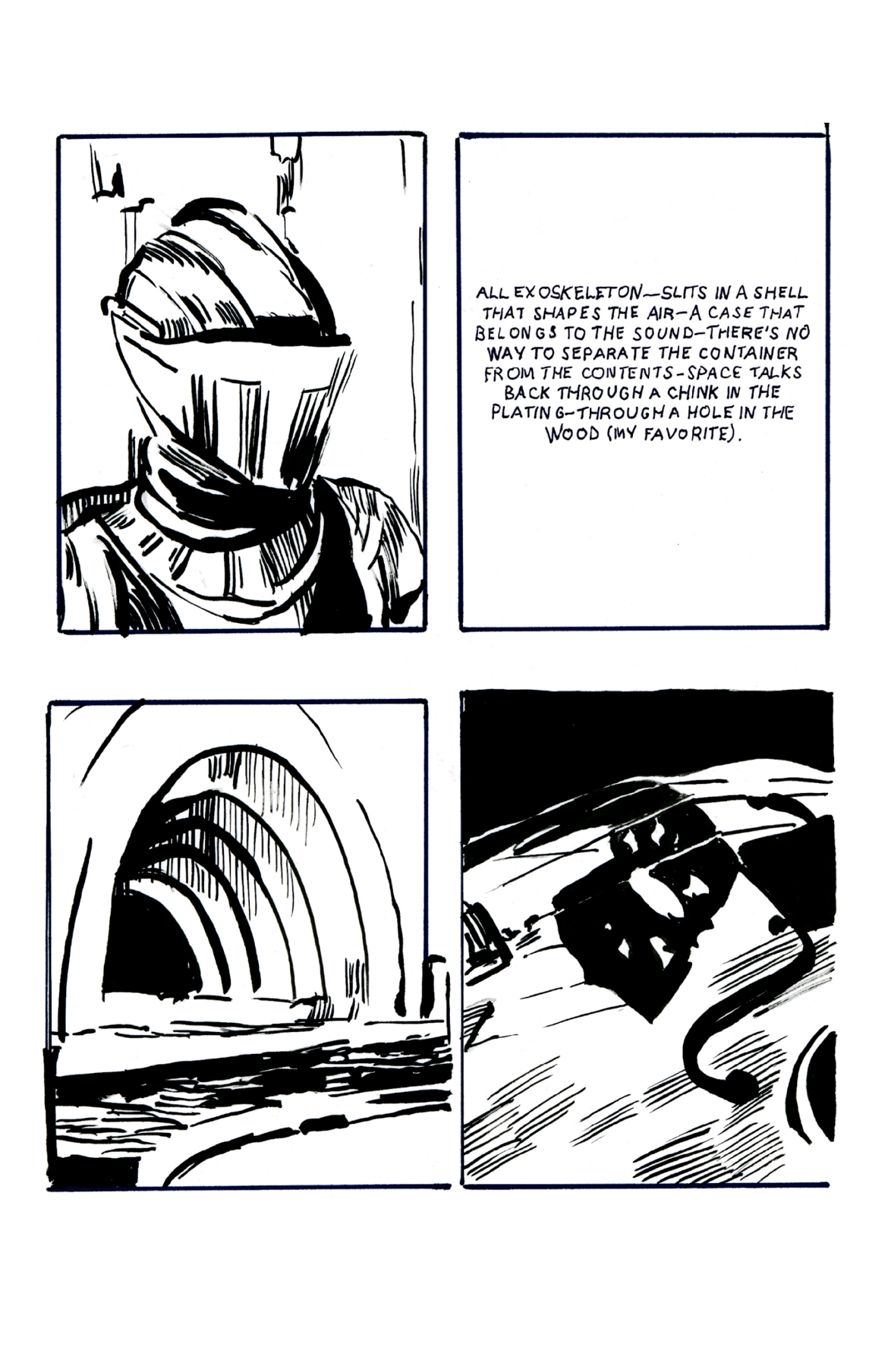

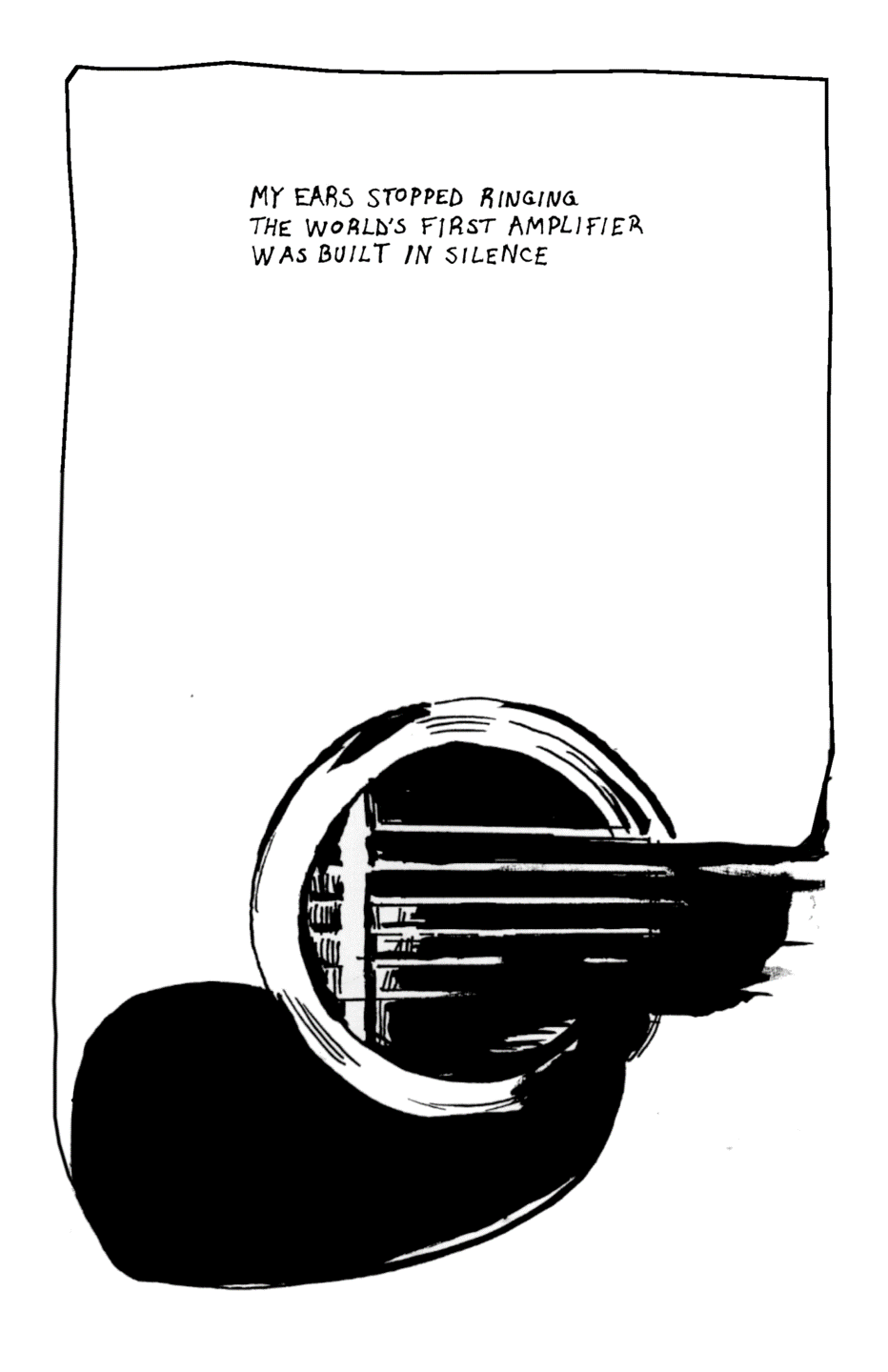

Plugging in cables and making photocopies: it’s a limited skill set, but I’ve spent years with these things. I’ve made music on my own and played with other amateurs in grubby little bands. Making music is obviously fun, but I also find a lot of joy in simply setting up, and trying out gear, drafting song lists, and making flyers for infrequent performances. In high school, my after-school job was working in the “Media Centre” of the school library: retrieving carts of AV equipment from classrooms, setting up the PA system for assemblies, and making photocopies. I’m fifty-one years old and still puttering around with this stuff in some form or another as I try to build stereos and self-publish zines. That being the case, I find myself meditating on the oblique or ancillary facets of music, performance, and recording as a way to reflect on the solitude of studio life and the weirdness of being creative in public. What follows are excerpts from a few poetry comics I’ve made in recent years that take this on.

|

The impulse motivating all this work is the exchange between understanding experience through language, signs, and intellectual cognition versus understanding via one’s nervous system, body, and intuition. The Bauhaus teacher and colour-theory proto-minimalist Josef Albers said the aim of art is to see more than facts.

|

|

|

|

|

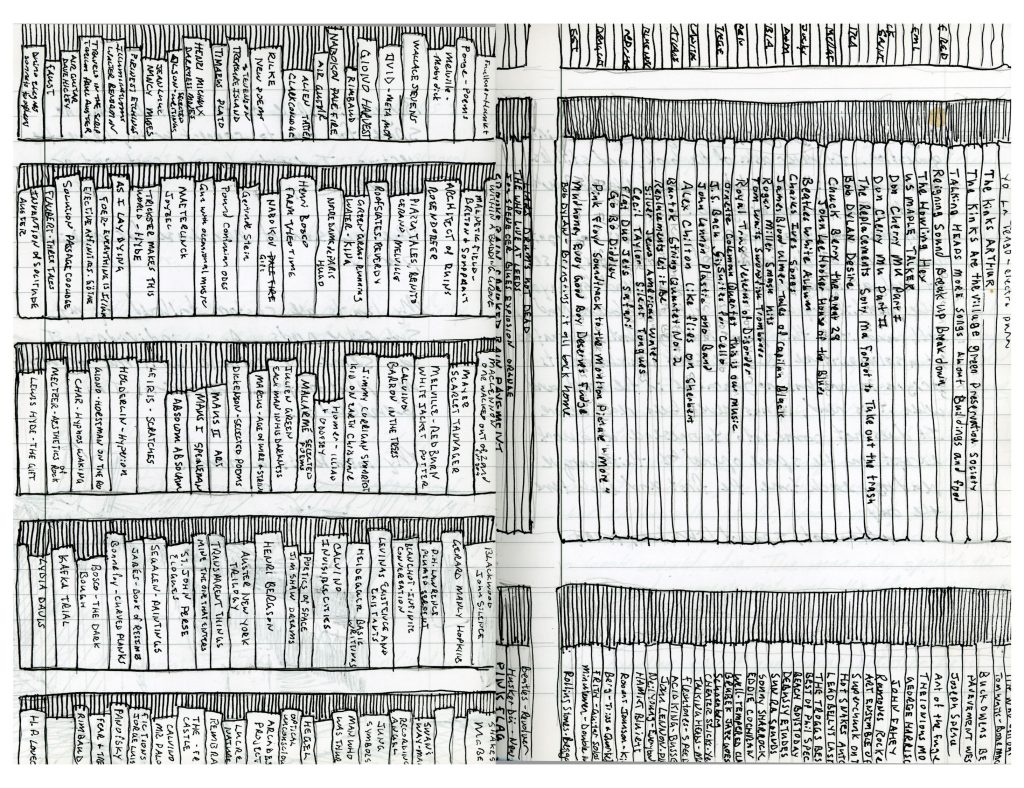

Connections: I want to be close to the stuff I love, and drawing it, like listening to it, puts me in its presence. Here is a drawing of books and music I’m crazy about. There is no attempt to render this with anything like accurate proportions or naturalistic space. It’s more of a list than anything. But taking the extra attention to write each title, author, and musician down in little boxes was meditative. Holding all these works in mind and on a page is a way of invoking their content. In grad school, a visiting artist said to me that it looks as though I’d rather be adored by a dead author than by a living curator. It’s true, for better or worse.

|

|

| Drawings by Steve Stelling, Ink on paper. Licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) Licence. | |

To give my anecdotes and pictures some semblance of cohesion, I’ll just say I want to be in the midst of ghosts—including, but probably not limited to, long-dead artists, decades-old recording sessions, my personal history, the spectre of my long-gone dad, and so on. Practising my art, my hobby, my enthusiastic fandom for niche areas of culture are my methods of communion with these spirits. Even helpful message board participants are voices from another realm.

|

I’m returning to this drawing because the luminous spreading of these arcs between two structured poles feels the most analogous to what is special about listening. Sound blooms, spreads, and fills space with a presence ripe with potential for communing. It happens every time I listen, especially now that I can do so through equipment I built myself.

Sounds made by artists I love, vibrating the air in my room: these things, like the non-present presence of music, are the spirits I commune with every time I listen to music.

|

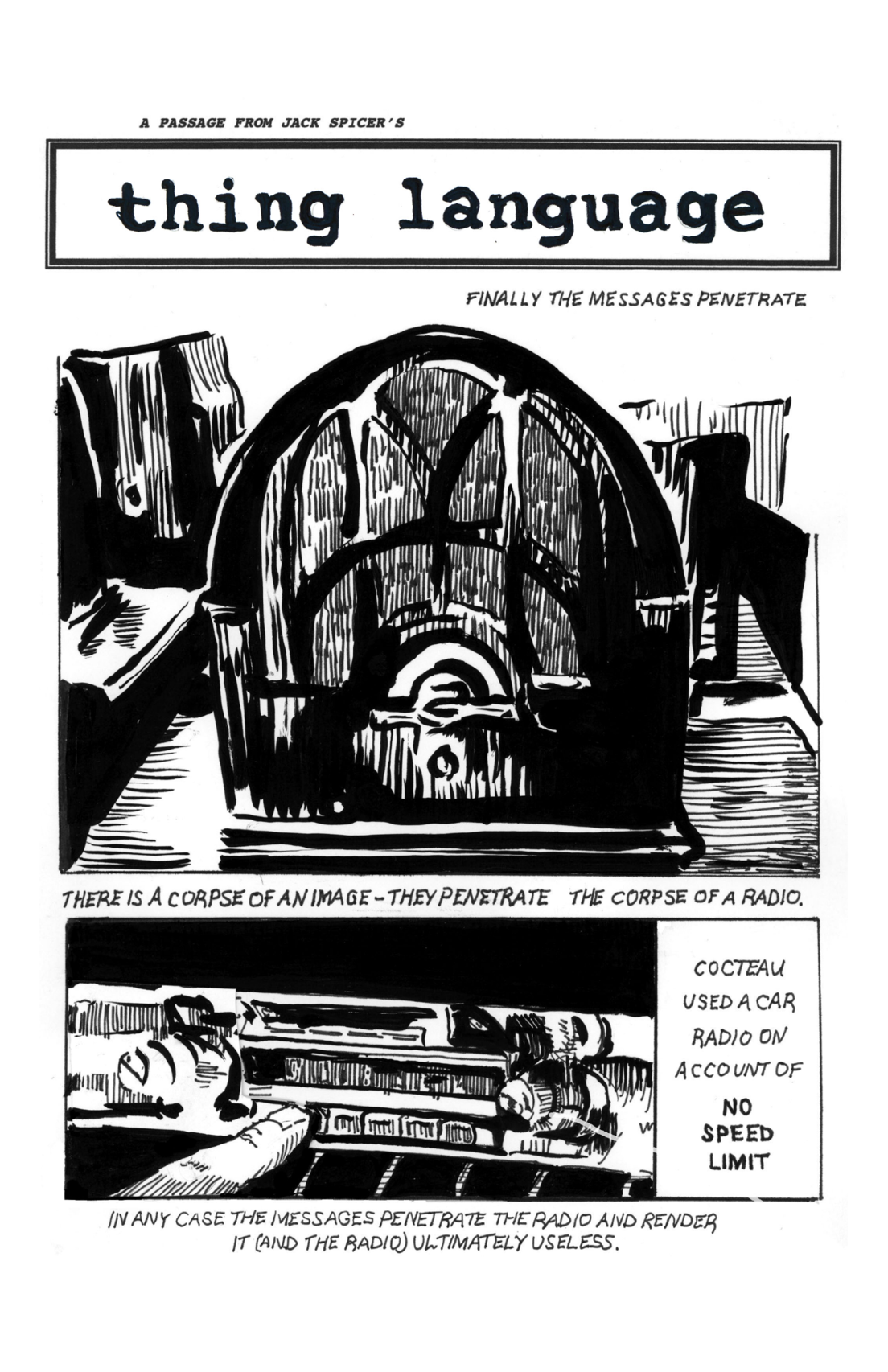

Finally the messages penetrate

There is a corpse of an image—they penetrate the corpse of a radio Cocteau used a car radio on account of no speed limit

In any case the messages penetrate the radio and render it (and the radio) ultimately useless

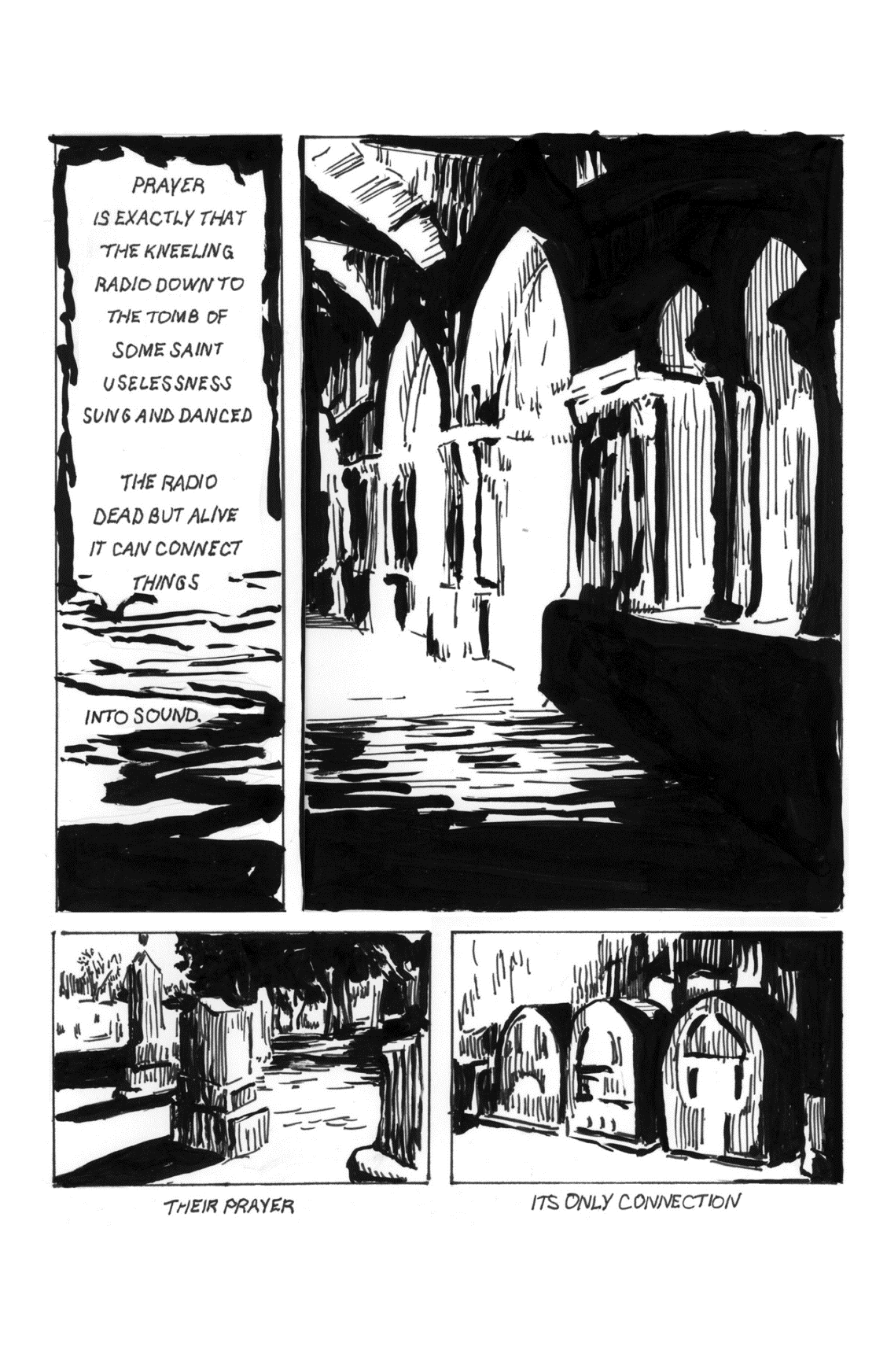

Prayer is exactly that

The kneeling radio down to the tomb of some saint Uselessness sung and danced

The radio dead but alive it can connect things Into sound

Their prayer

It’s only connection

Appendix: Because the artwork and ideas I’ve presented are anchored by my love for recoded music, books, and audio equipment, this appendix is a list of individual items that matter to me.