8 The Music of Deep Time

Sean Steele

Abstract

In this chapter I explore three musical works as a way to approach the concept of deep time through sound. Introduced by John McPhee in Basin and Range (1981), deep time refers to geological time spanning millions of years. I begin with a description of three musical performances: Jem Finer’s 1,000-year-long ambient work “Longplayer,” a 639-year-long performance of John Cage’s “As Slow as Possible,” and Brian Eno’s 2003 work Bell Studies for the Clock of the Long Now. I then unpack the concept of deep time and relate it to how these pieces stretch out the duration of musical sounds to offer a sonic metaphor for the vast panorama of deep time. Through the composition and performance of music that spans human generations, these pieces offer a musical expression of deep time. By extending the duration of sound beyond Western musical conventions and audience expectations, these pieces invite a process of defamiliarization with our conventional understanding of time.

In the second half of the chapter, I explore how experiences of defamiliarization can destabilize a Western colonial chronology of events encapsulated by the discipline of history. The geological origin of deep time invites a more holistic sense of time that draws in rocks, animals, and plants growing and changing across the planet. The length of these musical works expresses deep time by drawing both past and future generations into the idea of the finished piece, which invites us into a reckoning of our minuscule place in time. A reckoning with deep time suggested by these musical works offers a decolonizing practice of detaching from conventional conceptions of historical time to encourage reflections on vast time scales beyond the scope of human frameworks for constructing a chronology of events. Deep time includes an ever-shifting epic ecology that zooms out from a Western homocentric idea of history, inviting reflections on the permeable nature of even our most seemingly entrenched ideas.

Keywords: Musical performance; philosophy of music; deep time; history

I have always liked ethnomusicologist John Blacking’s definition of music as “humanely organized sound.”[1] Music is sound organized in sequences that are (typically) interesting and often pleasant to the human ear. As an artistic medium of expression, music exists in time. Music requires duration to be heard; the passage of time is bound up with the humanely organized sounds of music. Because music is sound organized by and for humans, the scale of most musical works resides in a human time frame. As Philip Alperson writes in his book on music and time, for most musical works, “the duration of individual tones can be easily measured by the listener.”[2]But what happens if the duration of the humanely organized sounds of music is stretched out far beyond ordinary limits? What if the performance of an entire piece of music takes longer than the span of an average human life to be performed? How can the performance of a piece that lasts for hundreds of years shift our relationship to the organized sounds of music? How can music extend its duration to suggest a less human-centric and more planetary scale?

In this chapter, I focus on three pieces of music to work toward addressing these far-reaching questions. The first composition is a 639-year-long performance of John Cage’s “As Slow as Possible” on an organ in the St. Burchardi church in Halberstadt, Germany. This performance began in 2001 and continues until 2640. The second is Jem Finer’s “Longplayer,” a 1,000-year-long ambient work that began in 1999 and ends in 2999. The third is provided by the ringing sounds of the Clock of the Long Now, a long-term time-keeping instrument currently being built in Texas. To ground analysis of this third performance, I focus on Brian Eno’s 2003 album January 07003: Bell Studies for the Clock of the Long Now. Although Eno’s album conforms to the conventional duration of an album, the composer’s close involvement with the Clock of the Long Now and his generative composition process support the inclusion of this shorter work in the discussion.

I am interested in how music can aid our ability to understand what Finer describes as “the unfathomable expanses of geological and cosmological time, in which a human lifetime is reduced to no more than a blip.”[3] By drawing out music’s property of duration, while remaining within the harmonic system of Western musical traditions, these humanely organized sounds can invite us to hear beyond conventional understanding and listen to these pieces as a reflective practice. Pushing against the short-term thinking promoted by a human-centric time scale, these pieces offer examples of how listening can foster awareness of what has been called deep time. Coined by John McPhee in his 1981 book Basin and Range, the term “deep time” refers to the vast geological time scale of the earth’s formation and the gradual development of life on our planet. On the scale of deep time, humans are recent arrivals. In deep time, human history is a tiny, late addition to an epic story that has been unfolding for eons. From this perspective, the academic study of history offers a narrow narrative ultimately embedded in a vast array of events mapped on an ever-shifting landscape of people and places.

The sounds of deep time suggested by these three musical works can push us out of ordinary expectations of musical composition and performance to foster moments of defamiliarization. These experiences of defamiliarization act like a wedge, taking us out of conventional Eurocentric ideas about music composed and performed within Western musical traditions.[4] Similarly, these moments of defamiliarization can engender reflections on deep time that relativize settler-colonial historical narratives. Such stories infuse our understanding of chronological events into an idea of history: a pervasive narrative construction combining Western colonial concepts of time and place. By increasing the depth and breadth of our ability to listen and reflect on the deep history of our planet, we can work to defamiliarize a dominant Western historical narrative that places humans at the centre. At the same time, these pieces defamiliarize dominant Western conventions of musical performance, including the relationship between composer, performer, and audience. This dual process of historical and musical defamiliarization can help to cultivate a more humble and holistic understanding of our place on an ever-changing planet that is billions of years old.

Scholars and musicians have explored the relationship between musical composition and time,[5] analyzed the temporal elements of rhythm,[6] examined time within the context of specific experimental pieces,[7] and posed questions about the ways non-traditional music can disrupt our ordinary relationship to the passage of time.[8] Other scholars have taken a philosophical approach to address questions about the temporality of music and the affective power of music as an aesthetic form involving the passage of time.[9] Others have taken a psychological approach to exploring the subjective experience of listening to music and how these perceptions affect the personal experience of time’s passing.[10] Additionally, our perception of music has been approached from the perspectives of physics, mathematics, linguistics, and neuroscience to better understand how our minds and bodies infer meaning and respond emotionally to these humanely organized sounds.[11] Other researchers have blended these approaches, such as Natalie Hodge’s recent book Uncommon Measure, which takes a self-reflective approach to explore the mathematics of sound from the perspective of a performing musician.[12]

I approach three pieces of music as sonic invitations to a process of defamiliarization from human Eurocentric conventions of musical composition and performance. Such a process of defamiliarization has implications beyond the perception of music. By vastly expanding conventional experiences of listening to a musical performance beyond Western notions of musical duration, these works open a sonic pathway into deep time. Expanding the property of duration within Western Eurocentric ideas about musical performance invites a parallel critical expansion of Western historical narratives. Sonic reflections of deep time can foster analogous reflections on the widening of history as a construction of imperialist and settler-colonial states. Deep time subsumes any and all modes of organizing events as a chronological narrative into a broader panorama of continuous change. Reflections on these epic time scales spurned by music can pull us out of the centrality of a settler-colonial chronology of “discovery” and “progress” by situating imperialist historical narrative constructions as one passing form (among many) of attempting to order the complex unfolding of events.

I suggest these musical works offer a sound analogy to the gradual changes implied by our earth’s ever- changing forms, and that such analogies open pathways for hearing into the imaginative grandeur of deep time. One result of this process of defamiliarization is to invite us into a broader, more holistic perspective of human history that can destabilize dominant colonial concepts of history. In doing so, these musical works draw on (and experiment with) Eurocentric Western colonial concepts of musical composition in a way that can subtly challenge and subvert the dominance of these structures. As I explore in the second half of this chapter, these pieces—and the process of defamiliarization they invite—can be considered decolonizing practices of musical performance.

Three Musical Works of Deep Time

The first piece is a performance of John Cage’s “As Slow as Possible” in the St. Burchardi church in Halberstad, Germany. Cage was a composer, musical theorist, and foundational figure in American experimental music. His incorporation of chance, unconventional instruments, silence, and noise made him a pioneer of postwar American avant-garde music.[13] Formerly a convent for Cistercian nuns in the fourteenth century, the St. Burchardi church now houses an automatic organ currently performing the longest iteration of Cage’s piece. Cage composed “As Slow as Possible” in 1985. The score is eight pages long and contains a series of chords that are sustained for long periods. In the place where the tempo marking is indicated on the score—such as allegro (109–32 beats per minute [bpm]), meaning fast and bright, or lento (40–5 bpm), meaning slowly—Cage wrote, “As Slow as Possible.” Performers have variously interpreted this tempo direction over the years, with the length of the piece ranging from seventy minutes to twenty-four hours.

In 2001, the John Cage Organ Foundation in Halberstad built an organ capable of performing the piece for centuries. The history of the church organ and the city provided the length of the piece. The first organ that divided an octave into twelve half-tones was built in Halberstad in 1361. This instrument, and the tonal system it used, ushered in the equal-tempered tuning that is the harmonic basis of nearly all Western music. According to Rainer Neugebauer, 1361 marks “the birth of the whole of classical and modern music. This date, and the year 2000, the millennium change, is like a mirror.”[14] Since 2000 minus 1361 equals 639, that is the length of this iteration of “As Slow as Possible.”

The concert began with a seventeen-month rest, as indicated on the score, on September 5, 2001. The first notes heard on the organ began on February 5, 2003. The initial chord of the piece lasted 518 days. In an article on the piece, Henk Bekker observed that “the longest chord in the concert is . . . played for 2527 days,” beginning on October 5, 2013. This chord “consists of five notes, of which one . . . [was] paused on 5 September 2020 . . . [with] the next sound change . . . after 518 days on 5 February 2022.”[15] At moments indicated in the score, specifically designed organ pipes are exchanged within the instrument to play the pitches as written in Cage’s score. Entry to the church is free except for moments when the organ pipes are switched out to create the following note indicated on the score. These are ticketed events where officials from the John Cage Organ Foundation carefully change the pipes to begin the following note or take out a note at the proper time. There is a ticking countdown on the website for this project. When I checked on the afternoon of November 19, 2023, it indicated that there are 225,278 days, 20 hours, 58 minutes, and a visibly decreasing number of seconds left until the piece ends on September 4, 2640 (https://www.aslsp.org/das-projekt.html). When completed, it will be the longest piece of music in recorded history.

The second piece is a composition called “Longplayer.” Composed by Jem Finer, a founder of Celtic punk band The Pogues, the piece began on December 31, 1999, and continues until December 31, 2999. As soon as the piece finishes, the thousand-year-long loop restarts and runs for another millennium. “Longplayer” is based on a series of slowly rotating waveforms that create unique interactive patterns of sound. As stated on the Longplayer website,

The composition . . . results from the application of simple and precise rules to six short pieces of music. Six sections from these pieces—one from each—are playing simultaneously at all times. Longplayer chooses and combines these sections in such a way that no combination is repeated until exactly one thousand years has passed.[16]

The piece is composed as an infinite loop, so another is set to begin when this thousand-year cycle ends. The work was initially commissioned by Artangel, an avant-garde arts organization in London, and is now in the hands of the Longplayer Trust. On the afternoon of November 19, 2023, the Longplayer website indicated that the piece had been playing for 23 years, 322 days, 10 hours, 2 minutes, and a series of increasing seconds as I watched.

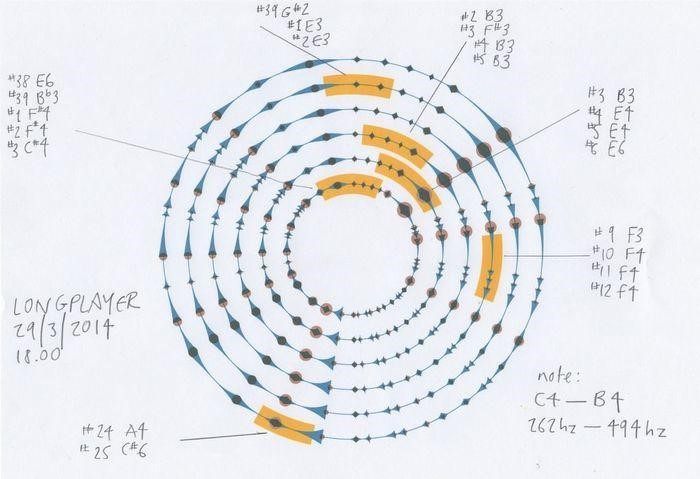

Although currently run on Macintosh and Linux operating systems using coding language from the Supercollider program, the composer and team who run the Longplayer Trust are aware of the eventual obsolescence of these technologies. To ensure the piece continues, there is a graphic representation that serves as a score for live performance.

Finer breaks down the system of the piece into five steps:

- Take one piece of source music.

- Repitch it into five transpositions.

- Play the original and the five transpositions simultaneously.

- Every two minutes, start again from a point slightly advanced from where you last started.

- Assign a different amount of advancement to each transposition and use it consistently. Repeat for 1,000 years.[17]

A tiny portion of “Longplayer” was performed live, using this graphic score, at the Roundhouse in London in 2009. As seen in the photograph taken during the performance, the bowls and performers are arranged to mirror the graphic score.

In addition to this 2009 performance, “Longplayer” is currently streaming at several listening stations that are open to the public. The flagship station is located at the top of the lighthouse at Trinity Buoy Wharf in London. Another is installed at the Yorkshire Sculpture Garden, and a third sits within the Long Now Foundation Museum in San Francisco’s Fort Mason.

An album is available through the Bandcamp website featuring four selections of the ongoing piece recorded between 2000 and 2002 (https://longplayer.bandcamp.com/album/longplayer). The Longplayer website also states that an archive of all recorded sound files of sections of the piece will soon be available to stream and download, offering listeners a chance to comb through the decades and hear a particular combination occurring at a specific date and time.

The third piece is an ambient album by musician and composer Brian Eno, influenced by his close involvement with the Long Now Foundation. The album is a series of sound studies inspired by the construction of a clock designed by Danny Hillis that will keep time for ten thousand years. As Hillis described it, he wanted “to build a clock that ticks once a year. The century hand advances once every one hundred years, and the cuckoo comes out on the millennium.”[18] A prototype of the clock was built in time to hear a chime as 1999 turned to 2000. A fully realized version of the clock is being constructed within a mountain in a remote location in Texas. Buried within a mountainside and deliberately built in an isolated location inaccessible by road, the clock is described as “an anti-monument” to emphasize how “the value of the clock is mostly in thinking about it.”[19]

Stewart Brand is a founding member of the Long Now Foundation. In an essay he wrote about the clock on the foundation’s website, Brand remarks that

Such a clock, if sufficiently impressive and well-engineered, would embody deep time for people. It should be charismatic to visit, interesting to think about, and famous enough to become iconic in the public discourse. Ideally, it would do for thinking about time what the photographs of Earth from space have done for thinking about the environment. Such icons reframe the way people think.[20]

Eno’s involvement in the Long Now Foundation, and the conceptual beginnings of the Clock of Long Now, began to intersect with his long-standing interest in ambient music—a genre whose name he not only coined but in which he has had a foundational role in forming and developing over the decades. Eno has used ideas drawn from cybernetics to avoid creating a musical composition in the traditional sense. Instead, Eno programs systems, or sets of rules, that generate interacting patterns of sound that he can either manipulate as they happen or allow to unfold organically. In a lecture he gave on this technique, which he calls generative music, Eno observed that most of his ambient pieces are “a system or a set of rules which once set in motion will create music for you.”[21] Part of the motivation for this system is that it takes most of the elements of personal creative expression out of the composition. In many ways, the artist who sets up the musical system is as much an audience to the result as an audience would be hearing that system unfold in a performative setting.

From out of this creative process, Eno created bell-like tones on synthesizers to explore the sonic parallels of the Clock of the Long Now. As he reflects in the liner notes for the album, “when we started thinking about The Clock, we naturally wondered what kind of sound it could make to announce the passage of time. I had nurtured an interest in bells for many years, and this seemed like a good alibi for taking it a bit deeper.”[22] His research led to the idea that using bells as a set of randomly interacting tones was an early form of generative music.4 Eno used synthesizers to model the tones of church bells, creating a system inspired by the generative music of bells to model the passage of long periods. He employed the idea of change-ringing, a generative system of various numbers of bells randomly interacting. As he states,

Change-ringing is the art (or, to many practitioners, the science) of ringing a given number of bells such that all possible sequences are used without any being repeated. The mathematics of this idea are fairly simple: n bells will yield n! sequences or changes. The ! is not an expression of surprise but the sign for a factorial: a direction to multiply the number by all those lower than it. So 3 bells will yield 3 x 2 x 1 = 6 changes, while 4 bells will yield 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 24 changes. The ! process does become rather surprising as you continue it for higher values of n: 5! = 120, and 6! = 720 – and you watch the number of changes increasing dramatically with the number of bells. [23]

When the number of bells is 10, Eno observed that the combination creates 3,628,800 interacting sequences. If a person were to ring out one of those sequences per day, it would take ten thousand years, which is exactly the time span of the Clock of the Long Now.[24] The album’s title refers to the time and year at the mid-point between the record’s release and the date at which this sequence of bell-tone interactions would finish. Collaborating with Hillis—who provided the mathematical algorithm to figure out the particular tone sequence on a particular day—Eno created music that sounded out potential futures heard as a unique set of bells ringing from some imaginary tower. As Eno states, “the title track of the album features the synthesized bells played in each of the thirty-one sequences for the month of January in the year 07003.”[25] In their article on some of Eno’s ideas behind his music, Austin Brown and Alex Mensing add that

Although the album itself is only seventy-five minutes in length, making it the shortest and most conventional piece of music I am exploring here, the soundscapes Eno created are a musical exploration of Danny Hillis’s clock and were inspired by the relationship between clocks, the generative music of change-ringing bells, and the sound programmed synthesizers recreating the sound of bells.[26]

I agree with Eno that “it’s ironic that, at a time when humankind is at a peak of its technical powers, able to create huge global changes that will echo down the centuries, most of our social systems seem geared to increasingly short nows.”[27] These three pieces are an attempt to use music and technology to push against the “short nows” of our world. Music joins other forms of artistic expression, which can stimulate our imaginations and bring us out of habits of thinking and feeling. Many of us are inundated with information and stimulation, bombarded with the proliferation of instant gratification offered by smart phones and computers. Through our commitments, we are typically focused on time spans of a week, a month, and (perhaps) a year. For many of us, our busy, technologically integrated lives keep us relegated to a series of “short nows.” These musical works attempt to use music and technology to push against the “short nows” filling the emails, calendars, calls, and schedules of everyday life and allow people to imaginatively hear music that will echo down the centuries.

There is, of course, nothing inherently wrong about a focus on the here and now, on living according to the more immediate demands of the day. But it is important to occasionally perform a mental zoom-out and think about how our busy lives flow within a vast network of other lives, both before and after we are alive. Zooming out even farther, our human network exists within a planetary ecology that has evolved for millennia. Speaking about his motivation for composing “Longplayer,” Finer writes that “at extremes of scale, time has always appeared to me as baffling, both in the transience of its passing on quantum mechanical levels and in the unfathomable expanses of geological and cosmological time, in which a human lifetime is reduced to no more than a blip.”[28] In his book Deep Time Reckoning, Vincent Ialenti calls for “analogical thought experiments [that] can help us distance ourselves from our time-bound worlds, defamiliarize them, and imagine them afresh.”[29] These musical works offer analogical sound experiments that push us out of ordinary understandings of musical performance and open the possibility of imagining the deep time involved in the formation of the planet that sustains us all.

Deep Time and Music: Decolonizing History Through Sound

“Deep time” refers to periods spanning millions of years that comprise the geological eras. McPhee observed that most people tend to “think in five generations—two ahead, two behind—with heavy concentration on the one in the middle.”[30] The geological inspiration for deep time zooms out from this human-centric time scale to situate these five generations within a panoramic view. Deep time urges us to pull back from what McPhee describes as our “animal sense of time.”[31]

But it can be difficult to move beyond this essential quality of our mammalian mind and perceive the immensity of time recorded in the earth’s mountains, valleys, and ocean floors. Geological time is not “readily comprehensible to minds used to thinking in terms of days, weeks, and years—decades at most.”[32] One way to offer suggestions of other manners of perceiving is through artistic expression. Most musicians and the pieces they compose reside within these human time scales. Our preoccupation with short-term thinking and individual pursuits makes the belief in broad goals impacting humanity difficult. In his book The Time of Music, Jonathon Kramer writes that, “while we can have a sense of direction in our daily lives, it is difficult to maintain belief in large goals held by all of humanity.”[33] These musical works open the possibility of reflecting on how and why these large goals feel challenging to maintain.

Ann McGrath and Mary Anne Jebb’s 2015 book Long History, Deep Time “asks whether it is possible to enlarge the scale and scope of history.”[34] These three musical works suggest similar questions about the scale and scope of performance that can be used as a way to reflect on deep time. The current conventional scale and scope of human history involves pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial periodization, which has been created and sustained by Western colonial knowledge industries.[35] The idea of traditional academic history is that “we can assemble all the facts in an ordered way so that they can tell us the truth or give us a very good idea of what really did happen in the past. . . . It means that historians can write a true history of the world.”[36] School curriculums teach history in these terms, university history departments must grapple with these Western constructions of human relationships over the centuries, and students of various backgrounds must navigate a narrative supplied by institutions that have maintained their position of power as the keepers and disseminators of historical knowledge.[37]

But more recent critical approaches that challenge this colonial narrative of history remain caught within the conceptual framework imposed by this idea. As McGrath writes, “by not challenging the datelines, even ‘postcolonial’ and ‘decolonising’ histories inadvertently validate imperial and coloniser sovereignties.”[38] These critical approaches to history are often forced to use the tools of the colonizer—literacy, research, and writing—to critique the tools themselves. Linda Tuhiwai Smith argues that “the characteristics and understanding of history as an Enlightenment or modernist project”[39] means that the chronology of history is the narrative justification for the consolidation and perpetuation of structures of power and control. This perspective does not invalidate or ignore knowledge gained by the project of history, but rather situates it within a socio-cultural and political context of Western imperialism and colonization. Deep time, on the other hand, relativizes the importance of any and all human attempts at periodization.

By marking eras spanning hundreds of millions of years, the geological foundation of deep time invites us into grand epochs that can help to situate any attempt to narrativize a chronology of events on a scale that can work to invalidate the structural force of colonial ideas. From the perspective of deep time, the Enlightenment occurred moments ago, and the modernist project of colonial history will be over in another moment. Deep time asks us to think and feel on a larger scale than pre- and post-colonial. The scales of deep time transcend historical periods spanning generations—such as the so-called Age of Discovery between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries—and invite us to situate these among the millions of years involved in the formation of mountains and oceans. The grander the scale, the less importance we might place on the dominant narrative that structures how we currently think and talk about human history. This perspective does not diminish the lived reality of the colonized, who remain disempowered, but prompts a conceptual zoom-out that allows us to see the entire arc of history as merely one version of some epic human story.

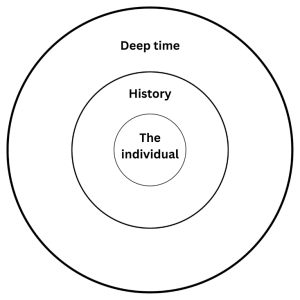

I find it helpful to visualize the relationship between the individual, history (as a colonial idea), and deep time as three circles sitting inside one other.

In the inner circle is the individual and their relationship to five generations—two before, two after, and one in the middle, of which that individual is an active member. The middle circle, which is larger, relates to how that individual views their relationship to history (including broad historical eras).[40] The third and widest circle is represented by the geological eras of deep time, which make even the most epic historical period a tiny slice of vast time. The inner circle represents the biographical narrative we construct regarding our lives or the lives of others. The middle circle represents various attempts to form a linear, chronological narrative of events as they are influenced and affected by individuals. The outer circle of deep time relativizes both the middle and inner circles as attempts to form a narrative out of small moments within a much larger span of time.

Henry Gee’s book In Search of Deep Time (2000) begins with the author pointing out that the “scale of geological time . . . is so vast it defies narrative.” While the fossil record discovered by humans provides “primary evidence for the history of life . . . each fossil is an infinitesimal dot, lost in a fathomless sea of time, whose relationship with other fossils and organisms living in the present is obscure.”[41] Humans use narrative to fill in the gaps to try piecing together a coherent story regarding the formation of the earth and the emergence and evolution of organic life. Importantly, Gee adds that “we invent these stories, after the fact, to justify the history of life according to our own prejudices.”[42] Similarly, the study of history is, in some respects, a story invented to stitch together a complex intersection of people, places, events, and ideas into an evolutionary tale of human progress and development. The time span of human history is far less vast than the geological deep time supported by the fossils, but it parallels the same narrative structure. As Gee continues, “fossils are mute: their silence gives us unlimited license to tell their stories for them.”[43]From the perspective of history, the voices of the colonized are often silenced (or left unheard). Traditional narratives of history divide time between pre- and post-colonial eras, effectively telling the stories of the colonized in the era before colonization occurred. In this story, the colonized are often mute, and the colonizers take the licence to create narratives of pre-colonial stasis as compared to the dynamism of historical progress (via imperialism, industrialization, and civilization).

By listening to a section of a piece of music we cannot hear in its entirety, we hear a slice of time unfolding. Just as a geologist views a slice of rock as a record of a certain period of the earth’s formation, these musical works offer the experience of listening to a section of an ongoing work in much the same way that a geologist knows that recent rock formations lying near the surface will be shifted into locations that will, in several million years, be unrecognizable. Music offers a record of sound, a resonance of humanely organized sound that does not remain as a rock does—but it offers the analogy of hearing what a geologist observes. To listen in this way is to hear inside and outside history simultaneously. In one sense, these pieces use conventional structures derived from a system of Western tonal harmony. But in another sense, these harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic structures are used in a way that points beyond Western conventions of performance and duration. In much the same way, deep time uses colonial concepts of history—taken as the attempt to stitch together otherwise disparate and complex events into a simplified, chronological narrative—to point beyond history (both forward and backward in time).

I agree with Ann McGrath that we “need to consider ways to think outside the usual constraints of historicised time.”[44] These musical works offer a way to think outside the conventions surrounding the composition and performance of music as humanely organized sound. In doing so, these epic pieces invite us to think outside the constraints of historicized time. Pieces like “Longplayer” offer a sonic strategy to guide listeners across generations, separating them from their current circumstances to incorporate a more holistic perspective of intergenerational time. By looping at the end of 2999 into another thousand-year iteration, “Longplayer” urges a further conceptual zoom-out that I find is best encapsulated by the idea of deep time. This broader perspective sees everything referred to as human history as merely the most recent chapter in an epic planetary tale of ceaseless change.

Such trans-generational pieces of music are “lacking an obvious fit with existing historical narratives of rather short pasts that self-consciously lead up to the modern present.”[45] They provide a glimpse of deeper time that moves backward to those sections of the piece that have come before, and forward to those pieces we will not live to hear. A work like “Longplayer” lacks an obvious fit with the performance and reception of music. Rather than leading up to the modern present, these works point toward the distant future. Drawing on ideas about our relationship to the deep past, they also incorporate reflections, dreams, visions, projections, predictions, hallucinations, and nightmares about the deep future. The effect of these incommensurable elements is the defamiliarization I find so useful.

For example, what might have been occurring on the site where the Roundhouse hosted the performance of “Longplayer” a thousand years ago, in 1009? What might be happening on or around the site of the organ in Halberstadt in another six hundred years? Will the Clock of the Long Now built into a mountainside continue to chime every thousand years? Will there still be humans around to hear it ring?

Conclusion

Stewart Brand writes that “Eno’s Long Now places us where we belong, neither at the end of history nor at the beginning, but in the thick of it. We are not the culmination of history, and we are not start-over revolutionaries; we are in the middle of civilization’s story.”[46] Such a view embeds us in a larger narrative. Music can help us feel that reality by placing us in a sonic relationship with what has come before and what will come after. I am interested in widening this perspective so that we can see past the boundaries of civilization’s story as merely one trajectory of one species on a planet that is billions of years old. The earth will continue supporting human life, or we will pursue a course of self-destruction. In both cases, the planet will survive for another few billion years. Listening to the time spans suggested by these musical pieces implies a long now that opens a pathway into a reckoning with deep time. This experience of reckoning can stimulate reflection on the colonial construct of history, allowing us to listen beyond the tumultuous sounds of modern progress so that we can hear other voices. These other voices have often been kept quiet or rendered silent by a Western chronological narrative. But these voices also include non-human sounds: the sounds of animals, the delicate groan of growing trees, and the nearly imperceptible shifting of tectonic plates.

These are far-reaching ideas, and I recognize that moving from a 639-year-long musical performance to the million-year cycles of deep time is a conceptual leap. However, I agree with Ialenti, who writes that “venturing to undertake deep time learning is more useful for cultivating long-term thinking than never embarking in the first place.”[47] To reckon with deep time is to play with the idea that, while “human consciousness may have begun to leap and boil some sunny day in the Pleistocene . . . the race by and large has retained the essence of its animal sense of time.”[48] Our mammalian brains have evolved to focus on short- term survival. McPhee is right to point out that we tend to think in five generations, situating ourselves in the very middle. But it is important to see how we might move beyond our evolutionary programming to consider how we as a species are integrated into a vast story of endless growth and change. The performance of a piece of music that takes longer than an average human lifetime to play out can shift our relationship to the organized sounds of music, extending our awareness beyond the human-centric paradigm of conventional musical performances embedded in Western traditions. This extended awareness can then carry over into an expansion outward from the human-centric narrative of history to a planetary scale that is millions of years old.

Works of art—including the musical works explored here—can provide cognitive and sensual experiences that offer opportunities to be pushed out of ordinary modes of understanding time. I agree with Eno when he writes that

What is possible in art becomes thinkable in life. We become our new selves first in simulacrum, through style and fashion and art, our deliberate immersions in virtual worlds. . . . We rehearse new feelings and sensitivities. We imagine other ways of thinking about our world and its future.[49]

The pieces of music I have explored here offer virtual worlds where we can imagine out beyond history and into deep time. Beyond pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial categories, deep time is a virtual world of erupting volcanoes, devastating earthquakes, crumbling mountains, and rising oceans. But deep time is also a world that includes us. Eno once said that “evolving metaphors, in my opinion, is what artists do.”[50] The humanely organized sounds of music can work to evolve the metaphor of history by situating it within a reckoning with deep time.

These questions of deep time prompt further questions. Will there still be humans born on this planet in five hundred years? Will there still be human ears to hear? Will people still be around to understand and follow Cage’s score and successfully change the organ notes on time? It can be difficult to imagine what humans might be doing in a thousand years. But music offers a poignant way to reimagine our relationship with each other and to the distant future. By envisioning how we are embedded in a vast and complex story involving rocks, plants, animals, and people, we can be inspired to care for the role we play in shaping the earth’s future so that subsequent generations have the opportunity to hear the final notes of “As Slow as Possible,” or listen to the first loop of the next cycle of “Longplayer” begin on January 1, 3000.

- J. Blacking, How Musical Is Man? (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1973), 6. ↵

- P. Alperson, “‘Musical Time’ and Music as an ‘Art of Time,’” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 38, no. 4 (1980): 408. ↵

- J. Finer, “Overview of Longplayer,” Longplayer.org, accessed March 21, 2023, https://longplayer.org/about/overview/. ↵

- For reflections on the Eurocentrism involved in the idea of Western and non-Western musical traditions, see T. Brett, “On Philosophy’s Western Bias: Thinking through ‘Non-Western’ Music,” Brettworks: Thinking Through Music (blog), July 19, 2012, https://brettworks.com/2012/07/19/on-philosophys-western-bias-thinking-through-non-western-music/. For a Western ethnomusicological attempt to understand and describe non-Western musical traditions (including their relationship with time), see J. Chernoff, African Rhythm and African Sensibility: Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), and S. Feld, Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kaluli Expression (1982; Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012). ↵

- Alperson, “’Musical Time’”; J. Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writing by John Cage (1961; Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2011); ↵

- R. Scruton, “Thoughts on Rhythm,” in Philosophers on Music: Experience, Meaning, and Work, ed. K. Stock (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 226–55. ↵

- M. Nyman, Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond (1974; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999). ↵

- R. Glover, J. Gottschalk, and B. Harrison, Being Time: Case Studies in Musical Temporality (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018). ↵

- S. Langer, “The Image of Time,” in Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art (New York: Charles Scriber and Sons, 1953), 104–19; R.W.H. Savage, Music, Time, and Its Other: Aesthetic Reflections on Finitude, Temporality, and Alterity (New York: Routledge, 2018). ↵

- S. Droit-Volet, D. Ramos, J.L.O. Bueno, and E. Bigaud, “Music, Emotion, and Time Perception: The Influence of Subjective Emotional Valence and Arousal?,” Frontiers in Psychology 4 (2013):1–12. ↵

- R.E. Beaty, “The Neuroscience of Musical Improvisation,” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 51 (2015): 108–17; A.D. Patel, Music, Language, and the Brain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010). ↵

- N. Hodges, Uncommon Measure: A Journey Through Music, Performance, and the Science of Time (New York: Bellevue Literary Press, 2022). ↵

- By “noise,” I mean that Cage’s music incorporated sounds that otherwise fell outside the purview of the humanely organized sounds typically understood as musical. Cage was motivated by the idea that any collection of sounds can be framed as music. See Cage, Silence. See also D. Nicholls, ed., The Cambridge Companion to John Cage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); J. Pritchett, The Music of John Cage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). ↵

- A. Gonsher, “A Visit to John Cage’s 639-Year Organ Composition,” Red Bull Music Academy, April 12, 2019, https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2019/04/halberstadt-john-cage-organ-feature. ↵

- H. Bekker, “Hear John Cage’s Slowest Piece of Music in the World at Halberstad,” European Traveler, July 5, 2020, https://www.european-traveler.com/germany/hear-john-cages-slowest-piece-of-music-in-the-world-in-halberstadt/. ↵

- Finer, “Overview of Longplayer.” ↵

- J. Finer, “Graphical Score,” Longplayer.org, May 2008, https://longplayer.org/graphscore/. ↵

- D. Hillis, “Wired Scenarios: The Millenium Clock,” Wired, December 6, 1995, https://www.wired.com/1995/12/the-millennium-clock/. ↵

- D. Hillis, “10,000 Years,” E-Flux, May 2019, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/digital-x/260423/10-000-years/. ↵

- S. Brand, “About Long Now,” Long Now Foundation, accessed September 29, 2022, https://longnow.org/about/. ↵

- B. Eno, “Generative Music,” talk delivered at Imagination Conference, June 8, 1996, San Francisco, CA, https://inmotionmagazine.com/eno1.html. ↵

- B. Eno, liner notes for January 07003 Bell Studies for the Clock of the Long Now (Opal Music, CD). ↵

- Eno, liner notes. ↵

- A. Brown and A. Mensing, “Music, Time, and Long-Term Thinking: Brian Eno Expands the Vocabulary of Human Feeling,” Brewminate, May 10, 2018, https://brewminate.com/music-time-and-long-term-thinking-brian-eno-expands-the-vocabulary-of-human-feeling/. ↵

- Eno, liner notes. ↵

- Brown and Mensing, “Music, Time, and Long-Term Thinking.” ↵

- B. Eno, “The Big Here and Long Now,” Long Now Foundation, accessed August 19, 2022, https://longnow.org/essays/big-here-long-now/. ↵

- Finer, “Overview of Longplayer.” ↵

- V. Ialenti, Deep Time Reckoning: How Future Thinking Can Help Earth Now (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020), 66. ↵

- J. McPhee, Basin and Range (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1981), 71. ↵

- McPhee, 71. ↵

- H. Gee, In Search of Deep Time: Beyond the Fossil Record to a New History of Life (New York: Free Press, 1999), 3. ↵

- J. Kramer, The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies (New York: Schirmer Books, 1988), 168. ↵

- A. McGrath, “Deep Histories in Time, or Crossing the Great Divide?,” in Long History, Deep Time, ed. A. McGrath and M. Jebb (Canberra: Australia National University Press, 2015), 1–31 ↵

- As Linda Tuhiwai Smith writes, “solutions are posed from a combination of the time before, colonized time, and the time before that, pre-colonized time. Decolonization encapsulates both sets of ideas.” L.T. Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (1999; London: Zed Books, 2008), 24; italics in original. Deep time encapsulates both while also looking farther back and farther forward. ↵

- Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, 31. ↵

- P. Lambert and P. Schofield, Making History: An Introduction to the History and Practices of a Discipline (London: Routledge, 2004). ↵

- McGrath, “Deep Histories in Time,” 8. ↵

- Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, 29. ↵

- This second circle can also include membership in a generation, such as Generations X or Z, a narrower category that fits within (and is partially defined by) a particular historical context. ↵

- Gee, In Search of Deep Time, 2. ↵

- Gee, 2. Italics in original. ↵

- Gee, 2. ↵

- McGrath, “Deep Histories in Time,” 6. ↵

- McGrath, “Deep Histories in Time,” 2. ↵

- S. Brand, The Clock of the Long Now: Time and Responsibility (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 31. ↵

- Ialenti, Deep Time Reckoning, 88. ↵

- McPhee, Basin and Range, 71. ↵

- Eno, “The Big Here and Long Now.” ↵

- Eno, “Generative Music.” ↵