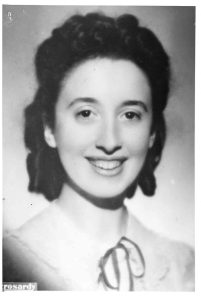

8 Jeanne Demessieux’s Diary and Selected Letters of 1940-1946 in Translation

I[1]

This notebook is strictly confined to precise events or conversations, not a word of which has been altered, relating all without commentary and without hindsight, for my personal recollection.

[signed] Jeanne Demessieux

[1] Sunday 8 December 1940

Vespers at St-Sulpice at 3:30 PM. For the first time, Marcel Dupré asked me to play his organ; he had me improvise the entrance music for Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament[2] (in the style of a procession) for a good length of time. In the middle of the improvisation he exclaimed,

“That’s beautiful, my little one!” and at the end, “what a beautiful improvisation; I am very pleased. It’s decided. Widor sat me at this organ when I was only twenty; that will bring you luck.”

Improvisation in E-flat minor on the hymn “Ave maris stella.”[3]

Monday 9 December 1940

Dupré announced in [the organ] class that I had played at St-Sulpice and asked me if I had ever dreamed of this.

Jean Gallon, when I told him this news, was very moved and said to me, “This is a great honour that Dupré has bestowed on you, an honour that you deserve. Here is my heart’s secret desire: once Dupré is named director [of the Paris Conservatory], he will not leave St-Sulpice, but will likely appoint a substitute; you will have your [Conservatory] prize and become substitute at St-Sulpice straight away, having, then, an advantage before becoming more. My feeling of friendship for you is as deep as for Marcel Dupré.”

Dupré made a point of [2] telling Busser that he had me improvise on Sunday. They spoke of my symphony; Busser said,

“She is writing me a symphony that is quite interesting but is not for the old fogies at the January exam; for that she will write a sonata for piano and violin.”

Wednesday 11 December 1940

Since I was speaking to the master about a feeling of fear towards art that I am presently experiencing, he said to me, “That is a good problem to have; don’t worry.” He confessed to me that he has never played or improvised in a concert, or in a service, and been completely satisfied with himself. He wanted to see my symphony. Recalling the day when I was introduced to him [in 1936]:

“I can tell you now: when I asked you how many little preludes and nocturnes you had composed in the style of the one in G-sharp minor that you had just played for me, and you responded, modestly, ‘Twenty-five… thirty…’ I thought to myself, “Here is a kid [petite gosse] with a brain. It is the only time in my career I encountered such a case.”[4]

[3] Saturday 30 November 1940[5]

I learned, confidentially, through the Conservatory administration, that the position of director will be open either very soon, or in a year.[6] They are pleading with me, as Dupré’s student and someone able to approach him, to let him know how much all the civil servants in the administration, as well as the entire musical milieu, wish to see Dupré named as Rabaud’s successor. I was warned that Marcel Samuel-Rousseau is seeking to make himself a definite threat.

On the advice of those close to me, following my own impulse, and out of loyalty to the Dupré family, I rushed to Meudon in the afternoon, aiming to impart this. Profoundly touched, they admitted to me that Jean Gallon had already spoken of it to Mme [Jeanne] Dupré and Marguerite [Dupré] two years ago. Dupré said to me, “Since then, a few of my dearest friends have spoken of it to me. I have never wanted to accept, because I am not a man of the theatre like Rabaud and because I do not wish to sit on the throne of Fauré, who (I dare say) was a genius.” But, at Mme Dupré’s insistence, I left feeling certain that they would accept, if the offer were made to them by the state. They both kissed my cheeks [in parting] after having kept me for an hour.[7]

[4] Sunday 15 December 1940

At my 11:30 AM Mass at St-Esprit,[8] I played the opening movement of the Symphonie-Passion by Marcel Dupré (at the Offertory) for the first time, then the chorale prelude with ornamented melody in G “Nun komm’, der Heiden Heiland.”[9] The first part of the Mass, improvised on the hymn “Creator alme siderum” (chorals [i.e., variations]). Postlude: improvised on a theme by Yvette Grimaud—beautiful (modulation and recapitulation in the subdominant, canons). Nine people in my gallery.

Sadly, I learned that Mr le Curé is in the hospital, where they had to perform emergency surgery.

Wednesday 18 December 1940

At the organ class, [we were given] a subject for a fugue and a symphony. The master found my symphony, “remarkable, individual, with attention to timbre and form.” He called my fugue one of the most beautiful that I have improvised in class.

He spoke to me about my sonata for piano and violin for which I have just finished an Adagio, and wants me to carry on immediately after with my symphony, which he wishes to get to know.

Dupré gave us a very profound definition of the artist (impossible to reproduce).

Friday 20 December 1940

After class, I accompanied Dupré as far as the [5] library, to speak to him and ask him to listen to my sonata and the fragment of my symphony as soon as I was ready.

He mentioned that he was very happy to chat with me to bring me up to date on the position of director of the Conservatory. Candidates’ applications are pouring in: Noël Gallon, for one, [and] the director of the Versailles Conservatory[10]—strongly backed by Busser—for another. Dupré does not want to get anyone to help him, and told me that the most worthy candidate would be named, even if it were not him (!)

Tuesday 24 December 1940

At 5:30 PM Mass at St-Sulpice (Midnight Mass). The master began playing at 5:15: Widor’s Symphonie-Gothique (I turned pages for him, though he played from memory), Sinfonia from the Cantata No. 29 by Bach, from memory. He improvised the Offertory (a noël); during the Communion: some extraordinary variations with hugely imaginative timbres; for the postlude, based on two noëls, a symphony in three movements—Allegro, Scherzo, Finale (in the style of a fugue).

Yolande was in the gallery and was magnificently received.[11]

Wednesday 25 December 1940

At High Mass [at St-Esprit], improvisations on noëls; d’Argœuves congratulated me. At 11:30 AM, I played the “Nativité” [movement] from [Dupré’s] [6] Symphonie-Passion for the Offertory. The rest of the time, I improvised on some noëls. Four people in my gallery.

At 3:30 PM, [attended Vespers at] St-Sulpice: Dupré improvised some magnificent versets that were profound, and a little melancholy. He had me sit on his left.

At 5:00 PM, my Vespers, which went very well; I created some versets, responding to the hymn. This evening and this morning, I was in brilliant form.

Sunday 19 January 1941

Feast of St-Sulpice. I asked for leave from St-Esprit so that I could spend the entire morning at St-Sulpice. High Mass: Dupré played an excerpt from Widor’s Sixth [Symphony] and improvised a symphony at the end. 11:15 Mass: Liszt’s great Fantasia [on “Ad nos, ad salutarem undam”].

Between the two masses, the master and Madame Dupré kept me for three-quarters of an hour in private conversation.

MD: “The more I think about it [Plus je vais], the less I understand what Busser said to you, in front of me, about your symphony. He finds it confusing, I find it very clear. I do not understand how he understands music. The same with Rabaud. I believe Rabaud has many young artists’ failed careers on his conscience. He is not my enemy, but he is the enemy of my success, even though I was his student.[12]

“As for the directorship of the Conservatory (this will [7] sadden you): Delvincourt will have it. It’s only a matter of forty-eight hours before it will be official; I can’t imagine any other outcome: Busser took care of everything.[13] I would have preferred to stay in my own little corner, to not have my name create such a fuss in this matter. I asked for nothing. I am sorry, to tell the truth, partly for ‘the family business,’ mostly for you.”

Dupré introduced me to Duruflé who said he remembered the last time I competed, having been on the jury, and judged my fugue as the best; Dupré responded [to Duruflé], “You are going to think I’m exaggerating… I set you apart because you are an artist; and I maintain that, of all those present, no one is capable of competing with a fugue improvised by Jeanne Demessieux.”

Before I left, my dear teacher made some humble remarks to me, which I will not reproduce, lest a false interpretation tarnish the genius of Marcel Dupré for the reader of these pages. These words suffice to summarize his meaning:

“I have always asked affection of my students, not admiration.”

[8] Sunday 26 January 1941

I’m reporting here [about] Wednesday, January 15th, when Dupré had me come to the Conservatory to tell me about some recent impressions of events concerning “the family business,” and entrust me with the copy of his work for the next Bornemann edition of Liszt. He asked me to look at the metronome speeds, the fingering, and made me promise to tell him whether my musical sense agreed with his or not.[14] He again wanted to see my symphony that I’d sketched out for him at Meudon two days before.

As we were leaving, we ran into Jean Gallon; they spoke about my sonata, the finale of which Dupré has urged me to develop further. He said he’s enthusiastic about my symphony and declared to Jean Gallon that if I do not receive my organ prize this year, he will resign.

I left with Jean Gallon, who said to me that he had never seen Dupré so very enthusiastic about one of his students. He [Gallon] was very happy about this. We chatted privately. Jean Gallon: “I know a little Jeanne Demessieux who will one day be a professor at the Conservatory. Oh, not tomorrow, but… soon! When that day comes, old Gallon [9] will be happy, and if Dupré were to be director… ah, well!…”

Wednesday the 22nd [of January 1941], Dupré had me come to Meudon an hour before class. I returned the score and played the Liszt for him by heart. Only one point on which I am not of the same mind as he: for the passage in G minor (arpeggios) the master has indicated 72 = quarter note; I find this too slow. We worked on it, then, MD: “You are right,” and he made a note. He was uncertain about the Andante, which he believed to be too slow, and asked my opinion; he decided to review the movement. I switched one of his pedaling indications. MD: “You really think that this is better? I’m asking in the interest of pedagogy; as a virtuoso, I can stray in a personal direction; but the moment you tell me that there is a better way of doing it, I believe you.”

Sunday the 26th, I played Liszt’s great Fantasia on “Ad nos” at St-Esprit.

Thursday the 23rd, Busser announced his official retirement.[15] As director, he named Paray, Delvincourt, Dupré.

Busser: “What would you say, Demessieux, if Dupré were no longer an organ professor? Would you cry?…”

Monday 27 January 1941

Rabaud will finish out the academic year.

[10] Tuesday 28 January 1941

For Noël Gallon, I played my sonata (with my violinist). He liked it better on the second hearing.

NG: “I’m somewhat afraid that the harmonies are too aggressive for the jury. It is aggressive as a whole, not in the detail, which is preferable. It’s well constructed; there are some imaginative timbres. Do you remember the first thing that you played for me; you were only thirteen! It was some Chopin. Up until then I had judged you to be an exceptionally gifted student, like Jean Hubeau. You have thrown me off course; I had said to myself, this child will never be a composer; she will always gravitate around some kind of influence. [But] now, do show me what you’ve written over the past three years, as I would like to take stock of the situation.”

Wednesday, 29 January 1941

Organ class; fine fugue. Piece on two themes.

MD: “That’s a beautiful [organ] symphony, a lovely piece; you made me wait for the theme. I did not notice you had it written out: careful! Be sure to tell me what Jean Gallon has to say about the sonata; I’ll see you tomorrow.”

I played for J. Gallon. I tried to find out if he considered my sonata aggressive.

JG: You are twenty years old and speak the language of your century. I’m with you. Your sonata is dissonant [âpre] and individual to you; [11] it’s rich. Don’t seek to please everyone! There will always be some who are crabby; old Georges Hüe will make a fuss. You have only to answer to yourself and to those in whom you have confidence and who love you, which is to say, Marcel Dupré.”

In response, I added that I also value his personal judgment.

Thursday 30 January 1941

Composition exam. My violinist, Micheline Bauzet (student of Bouillon and J. Gallon) played magnificently.

The atmosphere created by the jury was horrible. Dupré was beside Philippe Gaubert, Rabaud presided, and Busser was standing—agitated, and talking. First movement of my sonata: I heard Marcel Samuel-Rousseau say out loud, “What’s that supposed to be? A funeral march? [Something] in church for the entrance of the officiating minister!” Second movement: Busser was talking very loudly to [Samuel-]Rousseau; I heard [the word] “sad.” Third movement: Georges Hüe was furious, got up and exclaimed, “Just look at Dupré! Look! He’s listening to that! He thinks it’s beautiful! It’s scandalous, hideous!” At the very end, Rabaud said, “That’s fine,” without raising his eyes. I departed, crushed.

The next instant, I saw Busser, who in front of thirty people, reprimanded me in the [12] following way.

B: “Oh, it’s you! Yes, you! They found it hideous, horrible! They’re all wound up arguing about it.[16] Too bad for you: all you wrote were wrong notes. But, during the first years, it’s always that way; you have replaced Falcinelli.”[17]

I told Busser that I did not think this judgment was worth much because no one had actually listened to my sonata.

He left, repeating, “It was hideous.”

Dupré came out, saying, “My poor dear, I was not able to rescue you: they are all against me. They have been very harsh today: I have suffered for it. Tomorrow we will chat, and I will tell you what Rabaud said. Bye for now; I’m going to see Marguerite!”

I spotted my teacher again in the subway, looking for the right direction; I retreated. [But] seeing me, he took me by the arm [and said]:

“Come with me.” I remember this much [of what else Dupré said]: “I believe I finally understand what they are asking of composition students: a [style of] writing that stems directly from a given melody and figured bass, with no attempt to seek out imaginative harmonies, in a form that we could call, in a word, eighteenth-century pastiche. There is a class missing at the Conservatory, a [13] class for teaching these stylistic imitations, making the connection between the harmony-fugue [classes] and the composition [class].”

I asked, “What name would you give to this class?”

“Neither composition, nor study of forms, not even an introduction.”

Me: “This class would then be based on a misunderstanding.”

MD: “You’ve said it. And now, my little one, remember this: all the great musicians were misunderstood, derided, starting in their youth: you can’t be a great musician without going through this. I am telling you this from experience, and I’ll share this much: I myself have known grave insults. Today I was once again subjected to direct attacks on my artistry. For you it will be the same.”

Marcel Dupré left, telling me again not to forget this.

Friday 31 January 1941

I went to see Noël Gallon at his morning class to ask him for a meeting. He wanted to chat and kept me for a half hour. I told him I’m discouraged and shared my impressions with him. He told me that my sonata was much too advanced for the jury and asked me what music I like. He was stunned when I told him that I particularly like Beethoven, Chopin, [14] Wagner and the romantics generally; that I like, but less passionately, Fauré, Debussy, Ravel, and that I find myself attracted more and more to the great classics.

NG: “Then, I don’t understand anymore, I do not understand.” And because he wanted to encourage me, I told him that I am at the point of asking someone I can trust whether I should continue to write or not. Noël Gallon was startled, began to stutter; then,

NG: “You believe, then, that I who started you on harmony, on fugue, who has seen you take your first steps, I am going to pronounce such a halt? This is serious: I cannot and do not wish to; and if I were wrong? An opinion more authoritative than mine is needed. Perhaps it would be good if you went to see Rabaud to present your case to him. Do you compose with difficulty or because you want to write?”

I responded, “I’ve been drawn to composition practically since my earliest years [depuis mon âge de bébé], but there’s a difference between childish [enfantin] enthusiasm and grand artistic aim. That’s what troubles me, because yesterday it became clear to me that I must choose.”

NG: “If you are writing from a desire [to compose], you must become a composer; I’ll ponder this; it’s a serious matter.” [15] He advised me to speak to Dupré.

In the afternoon, I waited for Dupré before the start of the class. He was worried: “Are you feeling better?” After a moment, we chatted. MD: “After leaving you yesterday, I spent twenty minutes with Marguerite (at the clinic);[18] out of twenty minutes, we spent fifteen talking about you. At lunch with my wife, we spoke only of you—and the same all evening. Last night I did not sleep, and this morning my mind is made up. Don’t listen to anyone! Do not believe what they are telling you! Right now, you are searching for yourself. Stay true to yourself! [Restez-vous même!] If you wouldn’t mind, I wish to speak to you in front of your classmates. First, though, have you something confidential you want to say to me?” With the master, I went back through my conversation with N. Gallon and, trembling, I asked him the same question that I told him I had posed to Noël Gallon: should I continue to write or not?

MD: “So that’s it… it has come to this… beautiful!” A pause. MD: “Remember the story of Glazunov asking Liszt this question? Do you remember Liszt’s response? [16] Well, my little one, here is mine: taking upon myself—accepting—paternal responsibility, I’ll permit myself to say to you, on my honour as an artist: you have been born to a career as a composer just as to a career as an organist and improviser; your life must be spent pursuing this aim. [Believe me when] I tell you, a child who, at nine years of age, wrote thirty nocturnes for piano is a born composer. Now, come.”

In class, Dupré asked my classmates for permission to speak with me at length in front of them. Publicly, he repeated the same words to me. Here is what Henri Rabaud said to him: “Among these young people [enfants], there are those who are in ensemble classes. I listen to them interpret Beethoven, Schumann, Mozart, sometimes in an admirable way; I am persuaded that they like this [music]. The same young people write ugly things, enough to make you believe they are not musicians. Others are in a harmony or fugue class; they know how to create something charming out of a given melody, or write a correct fugue; [yet] when they compose, they make ugly music. I [17] end up believing that they are not musicians. I am nearly convinced that I see them in their compositions, and that where I am mistaken is in believing them to be musicians based on a beautiful performance or a good bass [realization].”

The master spoke for an hour and a half, so magnificently that I dare not report, not being certain of every word.

I played two stations from [Dupré’s] Chemin de la Croix (fifth and ninth) for him.[19]When I had finished, he said to me,

“You certainly are taking this to heart [vous êtes bien touchée]! Rest assured, my little one; there will be [other setbacks] (I have had them), but of all the blows ones receives in life, the first is the hardest.”

As he was leaving us, this is what the master said to me:

MD: “Lastly, my little one, I say to you again: you are a composer! Don’t worry; go in peace.”

Concerning the fifth station from the Chemin de la Croix, I am reporting Marcel Dupré’s idea: a man, a labourer, is returning from work and meets the procession of the tortured Christ [Supplicié]; he retreats to the edge of the road to watch it pass, “the way one watches an accident.” A soldier orders him to help Jesus carry his cross; he obeys, without enthusiasm, but, touched by [18] divine grace, he adjusts his steps little by little to those of Jesus and, having achieved this, tries to carry the heavier weight.

Sunday 2 February 1941

Mass at 10:00 AM: [Yvette] Grimaud brought me a theme on which I improvised a symphony (not so beautiful). 11:30: I played “Choral mystique de l’Eucharistie,”[20] the Toccata and Fugue in D minor by Bach, improvisation[s] in the forms of chorale variations, a symphony.

I saw Father de la Motte, who said to me, “I have unlimited confidence in my little Jeanne. She can do whatever she wants in her art; I have confidence in her, and nothing will make me change. She can count on my support.”

Monday 3 February 1941

Marcel Dupré: “Would you believe that this child, who looks like an angel from heaven landing in our world of misery, would be capable of making a jury so angry, and that she could scandalize them so much that they find her language ‘too advanced’” ([said] in the organ class).

Wednesday 5 February 1941

M. Dupré had Jean Gallon come by the class, having said to me: “Here is a great artist who wishes to speak to you. You are going to end up smiling!”

JG: “What is Marcel talking about? What’s going [19] on?”

I said, among other things, that they have labelled my music “music of the mad.”

JG: “It certainly makes you wonder who it is that is mad!” He openly blamed Busser. He vigorously encouraged me.

JG: “Don’t listen to any of them; ignore that ridiculous old man (Georges Hüe). Only one person is worthy of your confidence: Dupré; my brother, and myself for advice and support. You will play your sonata for me again, and we will see, fairly, between the two of us, if—in view of the opinion here—there are things to be scratched out and tried again or if the whole thing is unredeemable. We’re going to try to find the definitive plan that will allow you to receive the prize in composition as quickly as possible, and then, ‘Bye-bye.’ In three or four years, people around you will be saying, Jeanne Demessieux has a personality [that is her own]. And later, you will be a professor here; that’s how it goes!”

I mentioned to him that Dupré had been attacked strongly at the jury.

JG: “Nothing surprising there; he’s starting to bother them a bit!” He laughed. “Things are going fine for him. Take heart, my little Jeanne, take heart.”

I returned to the class where Dupré exclaimed, [20] “She is smiling! For your sonata as for everything, you must tell Jean that I insist he promise to tell you everything he really thinks, as I can say he always did for me. He, with Augustin Barié, was supportive of my three Preludes and Fugues [Op. 7] two years before I won the Rome Prize.[21] Théodore Dubois, a member of the Institute, spoke of me to Widor, saying: ‘this little Dupré is very nice, a good musician; he’ll have a fine career as an organist, but he will never be a composer.’ Widor repeated this to me after my Rome Prize…”

I was improvising very badly and stopped in the middle of a symphony, disgusted. MD: “It is that unfair reproach that has upset you so much [fait tant de mal]! …” I told him I’d had a fever for several days. MD: “Tell me about it! Just ask my wife and Marguerite; for eight days we’ve talked of nothing but you at the table, and I dare say that you have preoccupied us as much as Marguerite’s infection [panaris]. Don’t worry; remember what Liszt said to Glazunov!”

I left with Jean Gallon; we chatted for three-quarters of an hour. He got me wound up, and [21] insisted I go to concerts as often as possible, especially to the Opéra. He has boundless enthusiasm.

I went to visit Noël Gallon, who kept me for two hours to have me play my works composed since 1935. Like me, he considers my suite and my sonata, written under the same conditions—for the jury and very quickly—to not truly be expressions of myself. He was reassured by hearing the sketch of my symphony and said that I am on the right track. He focused great attention on my preludes for piano. He told me he is still puzzled by my musical taste, though he recognizes a hint of classicism in my symphony.

Sunday 9 February 1941

11:30 Mass: Chorale (Bach) No. 50;[22] ninth and fifth of Le Chemin de la Croix by Dupré. Improvisations: chorale variations, symphony (on the Communion [chant] for Septuagesima Sunday).

At 5:30, a concert by Maurice Duruflé at the Trocadéro;[23] Dupré had insisted that I attend. I was able to observe the console in detail. Moving the organ case forward has had an enormous effect. Many [22] people present. Duruflé fell short of a huge success by not responding to the call for an encore and improvisation while enthusiasm was building.[24] I encountered Dupré and his wife. I spotted Grunenwald [as well as] Marchal, who attracted such a fuss that one could not get near him. Duruflé welcomed me kindly: “Ah! You’ve come!” I introduced my sister to him. The organ is interesting, but the foundation stops are weak, the mixtures a bit acidic, and the overall effect somewhat hard, lacking support. A mishap during the concert: a cipher on the Récit that they did not manage to fix.

Monday 10 February 1941

Organ class; I improvised a lovely fugue; Dupré found it interesting and “alive” (I did a rare stretto of the countersubject in class, my third experiment). Lovely free theme (by mistake, a discord at the reprise).

Dupré: “I can’t wait to hear what Jean (Gallon) will have said about the [violin] sonata! I’m very interested. I can’t get over Busser’s volte-face Thursday: ‘You could have a [First] Prize, or a Second Prize, in two or [23] three years, with the same jury, by presenting the same sonata; they would not remember and might [simply] be better disposed toward it.’”

Regarding the Duruflé concert: MD: “An artist must seize the moment when, there on the stage, he senses a growing fever of excitement in his audience. In several instances, this has launched a career.”

I played my sonata again for Jean Gallon. He devoted an hour to me after his class, just the two of us with my violinist.

JG: “The more I hear this sonata, the more I like it; that’s significant: it proves how good it is. First, I’ll say what I think. With all due respect, I do not agree with the jury. There is, here, a single idea, worked through; it is admirably written. Evidently, there is a conflict between your music and your person: you are angelic, delicate; one expects you to write berceuses, romances, and [instead] you write this music, which I like, and which is proud (in a noble way) and masculine, rough. For the jury, this is disconcerting. If I were a critic, I would not dare write anything after a first hearing of this sonata; I would ask to borrow the [24] score for a week. With these things, it’s necessary to reserve judgment at first: ‘I don’t like that,’ right off the bat, is a ridiculous statement. You have undeniable character. You can believe in this [sonata], as can we, because it is built on your past and backed up by prizes in harmony, fugue, organ, and piano, of which it is the fulfilment. You are a profound and erudite musician, a thinker.”

Jean Gallon sought to identify the “spots” that would have bothered the jury. After skimming through the score, he thought he could find none; he hesitated, afraid of making a mistake, then made up his mind.

JG: “If I were called Jeanne Demessieux, I would take up this sonata again during the next vacation and, without touching anything, I would try to present the same ideas in a language accessible to the man in the street; one has to treat the jury like a man in the street.” As an example, he gave the last measures of the Adagio (which he found well thought-out). I tried playing them for him with a simple harmonization.

JG: “That would work for the jury, though the audience would remain cool, in need of what you actually wrote.” And again: “What always works, regardless of the language, is rhythm. We experience rhythm, but it not so with harmony, which we analyze with the heart, the head, or the ear. This is why an Adagio is the most difficult to impose on a general audience. Remember this: you always need the ‘man in the street’; it is he who is right when he has the majority. The moral of the story for you, as the fable says, is that a mouse may sometimes help a lion [on a souvent besoin d’un plus petit que soi].”

J. Gallon promised to bring me the orchestral score of [Ravel’s] Le Tombeau de Couperin, as a gift.

Wednesday 12 February 1941

Jean Gallon had me call in at the Conservatory to collect the Ravel score.

Organ class: I improvised one of the most beautiful fugues (Dupré found it admirable) and a symphony that he called “a lovely bit of symphonic work”; he remarked on the beauty of both pieces.

Dupré’s definitive version regarding the composition class: “The professors’ misunderstanding is in failing to realize that a student needs to like what they have written, even if it pleases no one else. For students, the misunderstanding is not having the courage to do simple composition exercises [26] that permit them to study form.”

After class, I chatted with Dupré, who brought me up to date on his application. We chatted with Jean Gallon.

During class, Dupré said to me, “You’ve got all your sparkle back. That pleases me greatly.” I repeated what J. Gallon had said to me.

Thursday 13 February 1941

My birthday. My parents presented me with the Dubois’s Treatise on Counterpoint and Fugue,[25] knowing my desire to do a thorough review of counterpoint as soon as possible. They have also ordered many works by Marcel Dupré for me. My joy overflows.

Friday 14 February 1941

Yesterday, I met Mr Mazellier who spoke to me about the exam in these terms: “Don’t be discouraged. But still, what music! You could do much better with what you have learned. Do you think it is harder to write the way you write? Come now, give in to your impulses, write what you think; ah! Well, if this is your music! Then…” (It felt like the walls of the Conservatory were caving in on me.)

Today, the organ class: the master liked the [27] way in which I interpreted [Franck’s] Grande Pièce symphonique. [Improvisation on a] free theme (nice arrangement at the reprise) of which Dupré said, as soon as it ended:

“I can say it no other way: I liked that, my little one! Perhaps I am not a good teacher; perhaps I am wrong, but I prefer simply telling you what I think. There are some people who do not understand that no artist, of any age, can write without emotion.”

Monday 17 February 1941

Organ class: MD: “Good fugue; nice beginning to the free theme” (I didn’t continue).

Dupré gave me excellent advice on composition; he again advised me to write a fantasy for piano and orchestra (with winds in threes) for the competition.

MD: “They cannot reproach you for writing badly for piano, since they recognize that you play it magnificently. Write for winds in threes: don’t forget that you are in Paris. Allow your ideas to mature over time before writing; gather phrases, harmonies, orchestral arrangements, the way one cultivates flowers; it doesn’t matter if, for one drop of essence, it takes hundreds of flowers! Even so, there will be [28] people who do not like that particular scent.”

Speaking of my symphony, which I am orchestrating as I compose,

MD: “I admire people who compose directly for orchestra; I have known three: Paray, Litaize, and you.”

Wednesday 19 February 1941

Organ class. MD: “A magnificent fugue; there is nothing to say.” The symphony movement was a scherzo on two themes. MD: “That’s remarkably beautiful.”

I went to Jean Gallon’s, where I listened to Beethoven’s Mass.

Friday 28 February 1941

I was the only student at the organ class until 3:00. Dupré arrived with Duruflé; they chatted about the organ at St-Étienne-du-Mont, which is going to be renovated. When Duruflé left, I played the Grande Pièce symphonique, in its entirety, from memory. Afterwards, I noticed that Dupré’s eyes were moist; after a moment,

MD: “Now listen to me: when you give an organ concert, the audience will go to it just as one goes to take a lesson. Don’t worry about your future. You will have [29] a magnificent career as organist and composer… When Busoni played, one had the feeling of being at a lesson. That’s the ultimate mark of a great artist. I like the way you play the Pièce symphonique; it’s profound.”

On the subject of the directorship, MD: “I don’t know if I really have any chance. The freemasons tend to have it all wrapped up. Yet, I cannot make myself into a freemason.[26] There are two things in life I fervently hoped for: St-Sulpice and the organ class. If I were given a choice between St-Sulpice and the directorship, do you think I could renounce St-Sulpice? To you I can make my profession of faith: I have never degraded myself to seek an honour; I have the Legion of Honour because it was offered to me, and as soon as I cross the border, I stop wearing it. I can be reproached for nothing in my public life, nor in my private life. I know that there are those who have tried to turn my friends against me. If I were a freemason, I would never want to enter a church, take the holy water, [30] make the sign of the cross, kneel down, because therein lies the Phariseeism Jesus pointed to.”

I improvised on a free theme. MD: “A jewel.”

I left with Jean Gallon.

Monday 3 March 1941

Dupré, having learned that Busser does not want me to write a fantasy for piano and orchestra (there being another student working on a similar work), strongly encouraged me to write a large-scale organ piece.

MD: “One knows neither who will enter the competition nor who the judges will be.” He does not want me to ask for a leave from the composition class this year.

Wednesday 5 March 1941

MD: “An artist-composer has made his contribution to art when he is convinced of having created a useful work.”

I showed Dupré an Adagio theme that had come to me. He whistled it, stopped: “it seems beautiful to me….” studied it, then:

“What you have here is the Adagio of the symphony!”

I asked him if I could use it for a fantasy for organ.

MD: “I’ll have to think about it… I promise to think about it between now and Friday, and let you know.”

[31] Friday 7 March 1941

Before the organ class, Duruflé, Perroux, and Beuchet were there waiting for the master to talk about St-Étienne-du-Mont.[27] Duruflé drew me into the conversation and introduced Beuchet to me; we spoke about my organ and about St-Esprit.

In class, as soon as Dupré arrived:

“I’ve thought about your theme; it is the Adagio of your symphony. You resist because you were obliged to abandon your symphony several times. (Busser did not encourage you, and you listened to him out of mere obedience.) But the symphony is close to your heart and won’t go away… Whether you like it or not, you are writing your symphony, you are hearing your Adagio (he sang it from memory), isn’t that so?… Keep this beautiful theme for the symphony but think of something for organ.”

Saturday 8 March 1941

Composition class. H. Busser: “Be so kind as to tell Dupré for me that he is invited to my students’ concert, or rather, his wife and daughter, too, for he may not come.… Ah! In fact, he would not come for me; but for you—yes.”

B. to Mlle Deschamps: “In your first year [as a composition student] [32], you are playing it safe, unlike Mlle Demessieux, for example. She [Demessieux] has to have a Second or First Prize―Second at least.”

Me: “I will have nothing.”

B: “In composition one can remain five years without getting anything.”

Me: “This is what will save me!”[28]

B: “I telephoned Vichy yesterday evening and was told that the director has been named. Tell me his name, I asked. ‘Oh, we can’t tell you.’ All they would say is that the new director is a war veteran…”

Me: “So, it’s not [Marcel Samuel-]Rousseau any more than Dupré… it’s Delvincourt…”

B: “Tell your pianist that she must not be late (for the recital).”

Me: “Thank you for reminding me, Master. That often happens with her.”

B: “You won’t let me down, will you?”[29]

Sunday 9 March 1941

Concert given by André Fleury at the Palais de Chaillot. Beautiful concert, good response from the audience. A fine success. An encore: the Prelude in B major by Dupré. I was with Papa.

In the foyer, Papa introduced me to Fleury, who had the kindness to welcome me in these words: “Mlle Demessieux? You’re the one who improvises such fine fugues! I didn’t [33] recognize you for a moment, I’m so used to seeing you in the competition, without a hat! My father often spoke of you; he very much enjoyed going to St-Esprit. I am very pleased to meet you.”

We spoke to Monsieur and Madame Dupré, and Marguerite; Mr and Mme Touche and their charming [son] Jean-Claude; Thibaud, the singer;[30] some classmates. We noticed Marchal, who spoke briefly to Dupré. Same people I see at St-Sulpice.

Monday 10 March 1941

Extraordinary organ class. (I improvised first.) Dupré revealed something that my six classmates claimed to not understand but that profoundly touched [émeut] my artistic sensibility.

MD: “Since Saturday evening, I have been extremely troubled. Since the construction of my extraordinary organ, with which you are familiar, I have done, for friends and for others, some experiments in registration, experiments that I have never dared do just for myself, being hugely apprehensive about that [sort of thing]. Saturday, I was drawn, as though someone had me by the collar of my jacket, to do this experiment. I improvised, and at the end of the day I wrote six measures. Ideally, in my [34] opinion, one would superimpose timbres, to amalgamate them according to the colour, their intensity, vertically, instead of in succession. Discovering that encouraged me to write using a particular harmonic language that resembles one of my latest Preludes and Fugues, the one in E; one cannot write on only 4 or 5 staves; one must use an alto-C-clef. I believe I’m on the verge of discovering a scientific fact that will allow for the teaching of ‘orchestration’ in a reliable manner. Therein are the laws of nature concerning the relationships and intensities of timbres. It is trivial to compare timbres to colours or to vowels; but there are a few things that can be compared to consonants. A trumpet pronounces on its attack P, a violin V, a flute T, etc. Perhaps I am the victim of a mirage… Soon I will know if this mirage is reality. I believe that the ideal I seek will appear to me. I think only of that; I will share my impressions with you. If I am wrong, my children, you will indulge me…”

[35] Tuesday 11 March 1941

I chatted at length with Jean Gallon.

Wednesday 12 March 1941

Monday, March 10th, Busser spoke with Dupré in the foyer of the Conservatory. In the subway, I saw Dupré, who said to me, “Life is funny…” He then said to me, “… But… nothing has been done; you can still hope…”, and he led me to a coffee shop.

Today, Dupré spoke briefly to me:

“You must have been surprised the day before yesterday to see me with our associate!… The reason is that one should never forget: ‘Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.’”

In class, fugue and symphony. On hearing my countersubject, Dupré exclaimed,

“There is the right countersubject. I am erasing mine and putting yours in its place; I am a bit of a thief, don’t you know?…” For the symphony,

MD: “You have treated the theme just as I hear it. Nice colour, well constructed.” Fugue: “A beautiful competition fugue.” Verset (I did polyphony in 6 voices):

MD: “That’s very nice, admirably presented, very interesting; for the competition, this [36] would be interesting, except we mustn’t forget our great invertible [counterpoint], and the effect that it has.”

Friday 14 March 1941

Organ class. I was alone when the master arrived. A moment later Jean Gallon entered.

JG: “Are you alone, Marcel, my lad?” Seeing me: “I believe we can speak in front of Jeanne Demessieux…What’s new? I’ve been told that Busser announced in his composition class that Delvincourt’s nomination will occur any time now…” (It was I who apprised J. Gallon of this without having spoken of it to Dupré.)

MD: “I know nothing of it.”[31]

During the conversation, which, I recall, was very private:

MD: “I always told you that Delvincourt had the best chance, being severely disfigured… That’s why I did not want to run against him. In [the] Vichy [government], Delvincourt and Jacques Ibert were the preferred candidates;[32] [Samuel-]Rousseau was not, nor was I…”

JG: “Delvincourt is clearly an honest man, but I can tell you that the general consensus is for you: [37] everyone wants you… I wish to believe this right to the end.” Dupré tried to dissuade J. Gallon.

MD: “I believe that our youngster here is saddened not to see this realized… They are both taken aback!”

JG: “What’s certain is that in 5 years, all will have changed here, the people—even the people!… What will be the new trends? Busser has said to his students: ‘You could “go there” now.’”

MD: “Do you, yourself, consider Delvincourt’s music to be so modern?”

JG: “No.”

MD: “It’s not as easy as that to write ‘modern’ music! I confess to you, Jean, that I would like this child to graduate from here…”

JG: “Ah, yes; of course.” Then, “Her graduation from the organ class being such a long time in coming, she is bored!”

MD: “I believe we will see each other again, even afterwards.”

JG: “It’s obvious that you will have gone to Vichy…”

MD: “To take the waters? I did that once in 1936.”

JG: “No, you would have to cross the line… [into the unoccupied zone]. But you would not because you are Dupré, while for others, it is not so…”

MD: “If only you knew, Jean, what this school is like [ce qu’est la boîte, ici]:[33] it’s sheer hell [c’est infernal]!! I believe that my destiny is gradually to return [38] to private life…”[34]

Jean Gallon left, and Dupré confided his private thoughts to me.

MD: “Delvincourt needs to be director: it will be a joy for him. I myself have joy at home!… I have fully done my duty; I did my duty by applying for the directorship, by not withdrawing my candidacy… As far as I’m concerned, since last Saturday I have prospects [j’ai un horizon]…”

I pointed out to the master that since the appointment of a director lasted for some twenty years, in theory, a lot of music could be expected to pass “like water under a bridge” during this time, with very important consequences for young people. Dupré was thoughtful for a while, then: “That’s true; you’re right.”

Dupré spoke again to Jean Gallon:

“Now I’ll tell you again what I’ve said to the rare friends who could comprehend it; I have not yet begun to compose. I now have the feeling that I am going to compose. This may be only an illusion, but I don’t think so.”

Thursday 18 March 1941

I chatted for twenty minutes with Jean Gallon. His first words:

“No news?…”

“No, Master.”

[39] “Well, I’ve had some. For our great man, it’s not going as badly as he likes to believe.”

As I was leaving, he said to me, “I have hopes for our ‘saint.’ In this affair, only one student and two professors have been in on the secret. We form a little Trinity.”

Wednesday 19 March 1941

I informed Dupré that my sonata for violin and piano had been a success at Busser’s recital.* (I had telephoned Busser the day before to ask him to let me play my sonata despite the scandal at the January exam.) Dupré was bursting with joy.

MD: “There you have it: ‘they’ were obliged to listen to the sonata! (Rabaud, Mazellier, Georges Hüe, etc.…). It took guts for you to insist; it was a stroke of genius. Bravo!”

Jean Gallon attended the recital.

* [Squeezed into the bottom margin:] I was called back to the stage three times with very insistent applause. Marcel Delannoy, in Les Nouveaux Temps, demolished me, ferociously.[35]

Sunday 23 March 1941

Concert given by Noëlie Pierront at St-Germain-des-Prés; works by Jehan Alain.[36] I noticed Rolland, Duruflé, Fleury, Marchal, Lazare-Lévy. Dupré attended the first part with his wife. I climbed to the gallery where Noëlie Pierront received me with kindness that was very touching.

[40] Wednesday 2 April 1941

After class, Dupré led all his students to the Palais de la découverte,[37] the music section. A two-hour lecture-demonstration. I saw, for the first time, sounds visualized on a lit screen. [Also saw] a working model of windchests and pipes built by Cavaillé-Coll.[38]

Sunday 20 April 1941

St-Sulpice. At 11:15 AM Dupré played Widor’s Fifth Symphony (movements I, II, III, V), from memory.

Tuesday 13 May 1941

In Meudon, for Dupré, I played the first movement of my symphony, for which I just completed the [piano] reduction.

Wednesday 14 May 1941

Organ exam. Jean Gallon was on the jury, as were Norbert Dufourcq, Cellier, Marchal, Messiaen,[39] Panel, Mazellier, etc. Themes by Marchal. Delvincourt presided. The overall grades: Me, Very good [T.B., for très bien] (nice remarks on my technique); Marie-Louise Girod, Good [B., for bien]; Denise Raffy, Pretty good [A.B., for assez bien].[40] Messiaen personally congratulated me!

Friday 16 May 1941

Upon my arrival at class, Dupré said to me, “For two days, I’ve been thinking about symphonies… much more [41] about yours than mine.” He appeared troubled and told me he had discovered, as if through a prism, the fundamentally nostalgic character of my music. He compared [my symphony] with some of my other works and found this characteristic to be subtly present, veiled yet still a part of the vital essence of my symphony. Such deep study astonished me.

MD: “I do not intend this as a reproach: Chopin, too, was nostalgic. I like your music. But for the ‘establishment’ [at the Conservatory] the contrast is so striking between what you write and you, yourself! Physically!… Your playing, as much on the organ as on the piano, is sunny. So, too, are your improvisations; your compositions are sunny to anyone who beholds them. [But] over these there is a veil and, deeper down, this indefinable nostalgia. I am convinced that you are searching for yourself.”

Sunday 18 May 1941

Concert by Marcel Dupré at the Church of St-Pierre-de-Charenton. Before the concert, the master invited me to come up to the gallery. Once seated at the organ, he asked Édouard Monet, sitting on his right, to give me his seat, and I witnessed the concert from this place of honour. Dupré played from [42] memory; the two of us pulled stops.

Two details to remember: I got an unforgettable lesson on mastery and humility that came directly from ideas of the master; secondly, I heard Bach’s Magnificat in its entirety for the first time with orchestra and chorus.[41]

Thursday 22 May 1941

On the radio, I heard part of [Wagner’s] Tristan (half of the second act and the third).[42]

Sunday 1 June 1941

Pentecost. Cardinal Suhard came to St-Esprit for the first time. Full church. Maman and Yoyo [Yolande] attended the Mass, sitting downstairs. I played the Allegro from Widor’s Sixth [Symphony], Prelude in B major by Marcel Dupré, Toccata from Widor’s Fifth Symphony; and I improvised. My gallery was full of people.

Friday 6 June 1941

Organ competition. Jury: Jean Gallon, Duruflé, Fleury, Panel, Marchal, Litaize, Cellier, Noëlie Pierront, Marthe Bracquemond, Mignan. Delvincourt presided. Themes by Cellier.

My emotions ran high; I felt as if I were staking my future on my playing; I redoubled my efforts.

Delvincourt announced: “Mlle Demessieux?… Mademoiselle, the jury and I award [43] your First Prize unanimously. Mlle Girod, the jury awards you also a First Prize.” Raffy [received a] Second Prize.

I met up with Dupré, who was waiting for us in the café at the Montparnasse St-Lazare train station.[43] With him were Mme Dupré, Mlle Chauvière, Marguerite, and her friend Mlle Fernande Vignard. The master greeted me with open arms upon learning the results.

MD: “This is the first time in sixteen years that the results are exactly what I wanted: I’m so happy!” He couldn’t stop repeating this sentence. Speaking to me of my three [organ] competitions: “For three years I’ve been scared stiff that I might see you fall to pieces in my class! The first year I believed that you would bring down Jehan Alain and Segond; last year, I feared the enormous difference between you and your classmates, and this year, the same.”

Girod and Raffy arrived. The master embraced them.

He said again, speaking to Mlle Chauvière: “In sixteen years, two of my students should have had their First Prize in the first year: Messiaen and that one,” pointing to me.

Amusing detail: while leaving we passed a group of Germans, who were quite intrigued.

MD (aside): “Now that you have been triumphant, would you like me [44] to introduce you to our guests?” A charming witticism.

We accompanied them [the Dupré family] as far as the train for Rouen in high spirits. Everyone embraced everyone else. I have never seen the master so happy.

Jean Gallon had required that his entire class attend the [organ] competition. Since he had gathered his students in his classroom after the adjudication, I rushed over to throw myself into his arms before going to Dupré. He was rather gruff; no one moved a muscle.

JG: “That makes how many for you?… Four?… Ah well… keep it up!!”

At home, it was sheer madness. I have a strong impression that this day is like a milestone between my past and my future.

I humbly took news of my triumphs to Father de la Motte, who embraced me with tears of joy.

I went to bed [feeling] totally intoxicated.

Monday 9 June 1941

With Jacqueline Pangnier, I played the first movement of my symphony for Jean Gallon. “That’s beautiful,” he said. He did not elaborate and wants to hear it again in a few days.

Friday 13 June 1941

I played the Allegro for Jean Gallon again, with the Adagio [45] that follows and that I’ve just finished. Henri Challan was present at the request of J. G. When the performance ended, J. Gallon turned toward Challan:

“This symphony is polished… polished… is it not, my little one? What beautiful orchestration, rich. It’s great. Ah! it’s carefully crafted…”

Challan, with a hostile air: “She must have had a terrible job writing this orchestration with winds in fours… It’s uncommon.”

JG: “And you wrote it all directly for orchestra?”

“Yes, Master.”

Challan shook his head: “That must have caused you some trouble? It’s very difficult.”

J. Gallon asked to see the melody; he appeared to be “making up his mind,” but said nothing. We stayed to work.

Sunday 15 June 1941

Jean Langlais concert at Chaillot. More beautiful technique than Marchal, heard previously. A problem with the [stop] combinations.

After the concert, I went with Papa into the foyer. Langlais was quite curt. I was surprised because it was he, himself, who had invited me. We saw Mme Dupré and Marguerite and spoke to them for a long time; the master is playing in Besançon today.[44] Marchal received me graciously, inviting me to go see his gallery. Duruflé and Litaize were cordial. [46] Langlais’s only words, to be remembered and savoured: “So, you have come here to recover from [cuver] your First Prize?”

Tuesday 17 June 1941

Composition competition. In the morning, I played the Adagio [of my symphony] for Noël Gallon (who is already familiar with the first movement).

At the competition in the afternoon, four of us played my symphony. I was at the first piano with Yvette Grimaud (who had just been awarded her First Prizes in harmony and accompanying), who played the treble part. At the second piano, Jacqueline Pangnier with Rolande Falcinelli taking the bass. Irène Joachim sang my song, practiced that very morning. My performers displayed great skill, considering that they received the scores very late.

Ten jury members were in attendance. I saw Honegger, Georges Hüe, Kœchlin, Tony Aubin, Messiaen, Delannoy, Maurice Yvain, Grovley, Max d’Ollone. The entire jury gathered around Delvincourt to follow the orchestral score; but it wasn’t long before Tony Aubin went and sat down again. A deathly silence during the Allegro. The Adagio began auspiciously; but Busser, having taken an adjudicator aside, talked nonstop in a loud voice, from the first note [47] until the last, without any response from the other. The same during the song. A sense of failure was in the air. I was very nervous having had to defend my 4th place ranking against my classmates.[45]

The result is that, out of eleven participants, the six male students received recognition, the five female students did not. A First Prize: Gallois-Montbrun; a Second Prize: Desenclos, Landowski, Sautereau [class of Roger-Ducasse];[46] a First Mention: Pascal; a Second Mention: Martinet [class of Roger-Ducasse]. Fallen: [Tombées:] R. Falcinelli, Eliane Pradelle, Simone Féjard [class of Roger-Ducasse], Demessieux, Deschamps.[47]

I don’t know anyone’s opinion; Busser was paying me no attention.[48]

Friday 20 June 1941

Dupré (whom I had not seen [since the organ competition]), gathered us together in Meudon: Marie-Louise Girod, Françoise Aubut and her sister, recently returned from internment.[49] We arrived at 2:45 PM and left at 7:15. A warm and intimate reception. Marguerite was there; Mme Dupré served us a sumptuous feast.

From 5:00 to 6:30, the master played his organ for us (Litanies by Jehan Alain, the anniversary of whose death it is). A brand-new, full demonstration [of the organ]; improvisation.

The master pulled a manuscript of a few lines from the [48] back of a drawer: it was the sketch Dupré spoke of in class on March 10th: six measures, in pencil, very neat. (In playing them, use of sostenuto,[50] inversion at the octave, and divided stops. The master played the sketch twice, with different timbres. I had time to read it several times. I felt it was the sketch of a master; those few measures were of a beauty, a richness, a completeness in all details, truly a solution to Marcel Dupré’s anxiety. To me, they appeared to be not so much the impetus for an entire piece, but an already developed idea, just one, taking shape all at once, because his [musical] language is found. The fundamental discovery is, then, this amalgam of timbres and possibilities. The result: an unedited and already perfect concept and, with a little probing, sensitive harmony without harshness—a perfect balance.)

A walk in the garden. Dupré took me aside. MD: “Tell me, my little Jeanne, what are you going to do?”* (There had occurred, just a moment before, a dramatic incident—the Duprés having heard from Mr [Louis] Laloy that I had a Second Prize in composition [49]—huge disappointment.) With Marcel Dupré, I broached the idea of my taking a break [from my studies], which my family has proposed. He shut this idea down immediately. I felt inspired to speak of my career aspirations. Dupré responded with some of his observations about America. He wants to take a few days to reflect: “Come, Sunday, to St-Sulpice; I will be playing Vespers.”

* [Squeezed into the bottom of page:] A matter of principle (Dupré having the greatest respect for the freedom of others). But there is no doubt that he had made up his mind.

Sunday 22 June 1941

St-Sulpice, at Vespers.

MD: “You and your parents must have such confidence in me to literally throw you into my arms! I am touched.”

I said that my parents would like to see him.

MD: “I would think so! Ah, it is I who wish to see them. This is the first time in my career that I shall make such a decision, and I make this decision for you in whom I have as much confidence as in myself: in your technique, as in my own. This is also the first time that one of my students, one who is precious in all ways, has said to me: I want to follow your footsteps: that is the pinnacle I aim for. Here is a glimpse of the past that is well for you to know.”

Marcel Dupré told me of his longstanding desire [50] to mold his own equal [former un émule], a peer capable of having a brilliant career. He believed he had found this in Marcel Lanctuis,** and procured an engagement in America for him; but despite a good start, Lanctuis gave up on his career. He [then] found rich skill and promise [riche nature] in Messiaen and procured an engagement in Brussels for him; Messiaen refused, wishing to make his career as a composer and only wanting to be an organist to play his own works, in the way he wanted.

The master asked me to keep his intentions absolutely secret. These pages are being written to establish the authenticity of these few memories.

** [Squeezed into the bottom margin:] Lanquetuit of Rouen.

Wednesday 25 June 1941

Papa, Maman, and I visited Marcel Dupré in Meudon (the master having wanted me to be present). The master had a long conversation with my parents, impossible to reproduce in detail. My future, if God so wills it, is laid out, from this moment. An artistic pact is established between Dupré and me. The conversation lasted for two-and-a-half hours.

Sunday 6 July 1941

Present at my 11:30 AM Mass were: Mr and Mme [51] Descombes, Mr d’Argœuves, Mr G. Fleury, Mr Provost from Les Amis de l’Orgue. Symphony on a theme by G. Fleury .

At 9:00 AM I briefly visited St-Sulpice.

Monday 7 July 1941

I went to J. Gallon’s (at the Conservatory). He played Beethoven’s Mass on the piano. His entire class was there. A beautiful atmosphere.

Tuesday 8 July 1941

I went to Marcel Dupré’s in Meudon. He had me play Bach’s Fugue in D[51] while he listened from the back of the room “to hear the effect one more time.”

I brought him some documents, which he placed in my portfolio.

He revealed to me the secret of his technique, which I do not dare put into words.[52] MD: “I would like to teach it, were it not impossible. It’s a matter of initiation,[53] of instinct. What’s needed is to collaborate; I could only do it with you. I was only a child when my father discovered, seeing me play, this curious innovation, which he hastened to cultivate. He revealed this to me when the time [52] was right. I have never spoken of it to anyone but him. I would not have spoken of it to anyone had not Providence led you to me, to consider as my dear daughter to whom I will confide everything I know.”

Dupré drew a parallel between his childhood musical evolution and mine; he pointed out similarities. At the point where the comparison brought us to the discovery of “the artist,” I halted it. The master, believing he saw a lack of faith in me, said, “You have what I have, in your art and in your soul. What’s more, you bring your personal contribution, just as I made a contribution beyond Widor’s.”

He retraced the lineage of our tradition of the organ, naming, “Lemmens, Guilmant, Widor, myself, and you.” Marcel Dupré said again, in all respects, “I am doing for you what Widor did for me.”*

* I quickly acknowledge the fact that he did much more, and said this to him, one day, in front of Mme Dupré, who agreed.

[53] Wednesday 9 July 1941 [sic]

I took Mireille Auxiètre to visit Yves Nat, with whom I was not acquainted, but who welcomed us cordially, having received a letter of recommendation from Noël Gallon. He found Mireille to be gifted, playing very intelligently; he wants to have her apply to the Conservatory, but left no hope for her entry into his class. He wants to see her again in September, not before. I feel that this would be moving too slowly, so I ran over to N. Gallon’s, then to l’École supérieure, where I spoke to him at the end of a competition.[54] Mireille needs to feel totally supported by a teacher, beginning now, to give her the courage to take the entrance examination. Noël will put some pressure on Nat, we agreed.

Thursday 10 July 1941

I have learned of the unexpected death of Philippe Gaubert.[55]

Saturday 12 July 1941

I went to the Opéra, where a Philippe Gaubert festival is taking place. Germaine Lubin sang several songs (she had a terrible cold, to judge by the tissue she held to her face between phrases). Evening of ballet: [Gaubert’s] Alexandre le Grand and [54] Le Chevalier et la Damoiselle danced by Serge Lifar and Solange Schwartz. The first time that I have seen Serge Lifar dance: very impressive, and the same for the general choreography. Lifar’s technique is a revelation to me: strength and balance, expression.

Sunday 13 July 1941

Father [Marie Joseph] Rouët de Journel came to my 10:00 AM Mass; we set a meeting to introduce me to L[éonce] de Saint-Martin at 2:30 PM Vespers at Notre-Dame.[56]

De Saint-Martin, who was expecting me, welcomed me cordially, saying, straight away, that the door of his gallery was “wide open” to me. Those present: three men, three women, the priest. Petty expressions. He speaks easily, has natural poise, makes judgments casually. He breathes heavily while playing, nervously racing through the notes [courant après ses notes]. Plays the pedal with one foot; Swell box; arpeggiates the chords. Much use of solos when improvising; all outward appearances; rubato, pretty things, banalities, overlong passages, octaves. He played his Passacaglia [published as his Op. 28] for the postlude. I remained standing behind the bench the entire time. A certain [55] Mr René Blin opened fire on Messiaen; this reeked of pettiness.

I had time to observe the specification and layout of the instrument. I am drawn to the Contra Bombarde 32′. Splendid instrument. I think of [Louis] Vierne. Meditative thoughts about this milieu on the one hand and thirteen-year-old memories on the other.*

* I was seven years old when I visited Paris for the first time. Upon hearing the organ of Notre-Dame one Sunday, I was so well and truly taken by it that Maman prayed for me to become an organist, though at the time I seemed destined by my milieu for the piano.

Sunday 20 July 1941

In my gallery at 11:30 AM, Mr Bruel, secretary of the Conservatory; Mr Provost of Les Amis de l’Orgue; Yvette Grimaud (beautiful theme: variations, finale); Weissère.

At 3:00, pilgrimage from St-Esprit to Sacré-Cœur. I went along and played the little [choir] organ; below, Papa, Maman, and Yolande.

At 5:10 I met up with Dupré and Mme Dupré at the Chaillot Theatre for Litaize’s concert; Marie-Louise Girod and I were among the guests who had been invited to sit in their box: a remarkable honour. Beautiful concert. Litaize played [Dupré’s] “Fileuse” [from Suite Bretonne] magnificently. Franck’s Choral No. 3, full of painful rubatos. Alain’s Litanies. Improvisation [on a] theme by Busser: burlesque.

In the foyer, I shook hands and chatted with Fleury, Duruflé, Panel, Edouard Monet, Provost, Beuchet the [organ] builder, Rolland, [Antoine] Reboulot; I caught sight of Marchal, [56] Busser, Langlais, Messiaen, Norbert Dufourcq. Litaize was charming with me and my family. Dupré advised me to write to Busser to pave the way regarding the leave of absence. They chatted with my parents; the master had a touching word for my sister. We took our leave of them.

In the morning, 9:00 at St-Sulpice, Dupré, speaking to me about our collaboration: “You cannot imagine how important this new thing has become in my life. I believed I would never have a successor. I have found a successor capable of equaling and surpassing me. It is the duty of every artist of integrity to search for the one who will go farther than him.” The master improvised sublimely; the organ has just been tuned by Pérroux. Dupré introduced me to Jules Isambart, the builder of his organ in Meudon.

My sister’s thoughts after Litaize’s concert: “There are three organists in Paris who play the organ well: Dupré, you, and Duruflé.”

Tuesday 22 July 1941

Maman’s name day;[57] Papa presented her with her portrait [57] done in pastels: magnificent.

Upon entering my studio yesterday, I found my organ diploma, framed.

Wednesday 23 July 1941

Lesson at Dupré’s from 9:45 to 11:45. I played all the major and minor scales and [Bach’s] Fugue in D. For the first time in front of Dupré, I wore Louis XV heels.[58] My emotions are running high: I have never played his organ so well. After fifteen days of trial and error I sense that my technique has taken off. The master encouraged me, and said, “in a year, we will see clearly.”

He gave me a book of Alkan’s pedal Études in an out-of-print edition.[59] MD: “I’ve worked on these a lot. Here is what I still remember.”

MD: “I am going to write a series of twelve études for you, the manuscripts of which I will pass on to you as I go along; you will copy them. I will publish them. But if you don’t mind, I will not dedicate them to you. Do you understand why? That would bring you harm; the easiest weapon is the tongue.”

Dupré gave me much advice. He ran through an overview of contemporary French female organists [58]; none appear to be a threat (I listened to Dupré’s opinions in silence).[60] Three foreign artists, one of whom is of interest: he gave me their names. Two Italians, prodigious in acrobatics. No threat from male organists in France, but Dupré omitted mention of Duruflé…

MD: “I want to write a symphony for orchestra; I have my themes. I’m caught between two desires: to write it immediately, because I’m obsessed with it, and to wait yet so that it will be all the more beautiful, more mature. So, for the time being, I am writing an organ symphony in memory of Papa: the inauguration [of the organ] in St-Ouen is set for October 28; I want you to be there, incognito; I’ll pay for your trip; I’m pleased to do that.”

We looked for exercises in virtuosity; Dupré recommended pedal staccato.[61] For my next lesson, a heavy assignment in technique [and] the Prelude in A-flat [Dupré’s Op. 36, No. 2].

Saturday 26 July 1941

I received a message from Dupré by pneumatic dispatch.[62] He asked me to play Vespers at St-Sulpice and summoned me to Meudon to get my instructions; I went immediately.

He was giving a lesson [59] to Jeanne Marguillard and introduced me. The master explained the rite to me in detail. Made a plan for me, spoke to me again of his études: “This is just between us” (concerning the lending of manuscripts). I copied down the layout of the organ.

Mme Dupré welcomed me fondly. A meeting before High Mass [is planned].

Sunday 27 July 1941

8:45 AM, St-Sulpice. Detailed explanation of the instrument; advice. MD: “Take off your gloves: you are going to play the entrance music.” Dupré spoke some more about our projects, like yesterday: “I can think of nothing else.”

At 3:30, Vespers. I was quite frightened but itching to play. The organ sound was magnificent; I was transported. Entrance music. Hymn: first [verset] in plainchant tutti, second: canon at the fourth between soprano and bass, in four voices. Magnificat versets: foundation stops G.O.-flutes-mixtures-reeds. R[écit] pp—and the last [verset], Cornet with Bourdon 8′, but… the Cornet did not sound: I had forgotten to set the piston; I salvaged the situation; Papa, who never suspected a thing, told me he liked this verset the best…! The bell rang at the last verset, which seemed likely to go on, and with good reason: I [60] never wanted to stop.

That very evening, I wrote to Dupré.

Sunday 10 August 1941

8:45 AM, St-Sulpice. I made the illustrious acquaintance of Madame Dominique Jouvet-Magron, to whom Dupré introduced me. In speaking of Mme Jouvet-Magron, he told me, “… the greatest painter of our time.” She is currently working on an important realist composition that Dupré saw yesterday, and that he considers splendid. The conversation began in the parlour and continued around the console: Mme Jouvet-Magron sat to the master’s left and I to the right. The person accompanying Jouvet-Magron seemed excluded from the very friendly conversation. Dupré, as is his wont, did “lay some groundwork” by talking a lot about me. I honestly remember: MD: “When you become a member of the [French] Institute, Magron, you must not forget to vote for Jeanne Demessieux for the Rome Prize! It would be amusing to see the two of you there! I would give anything to spy through the keyhole to see Magron on the committee.”

Me: “You would be much better off seeing it from the inside, [61] Master.”

MD: Oh, no! You will never see me in the Institute. What a life! I was a candidate for something once in my life, for the organ class: I swore that I would never do that again; the lobbying one must do!… (abruptly). I’d like you to play the Adagio for me, from your symphony that I have not heard. You will come to Meudon. I think you must finish the symphony before anything else.”

Me: “Yes, I cannot get it out of my mind.”

MD: “It is well within your power, so write it; I can also tell you not to hurry.”

Jouvet-Magron: “A symphony? For orchestra?…”

MD: “Yes, written directly for orchestra, just like that.”

Me: “It’s just a sketch, the first one I am writing.”

Jouvet-Magron: “My child, I would think so, to see you, that this would be the first!…”

MD: “This little one is going to be a great artist; I have great hopes for her future. You will bear that in mind?” During the sprinkling of holy water [Asperges]:

MD: “Jeanne, look, the officiant is going into the congregation; he is not going around the church; a verset must be played; when he gets to the foot of the altar, you stop. I have the wrong book; bring me the Parisian Propers.” [62]

To Mme Jouvet-Magron, MD: “This child can stay no longer at the Conservatory, where she isn’t happy, except in Jean Gallon’s class, and in mine, perhaps. Her downfall was the class of that Spaniard Riera, who is so irascible; she worked one year with Magda Tagliaferro, who fell in love with her, of course! She left for America, sorry to say. She [Demessieux] did not loiter in Jean Gallon’s class; with Noël she was not unhappy; with me…” I tried to interject, but I was cut off. Dupré continued: “In composition, she is like you and me: she has a personality, and for that reason, she suffers. It’s not right when a little child of 19 is already being insulted for her music![63] ‘They’ did not like her music!”

Jouvet-Magron: “My child, if they say bad things about your music, it’s because you are beginning to make them feel uncomfortable… and you certainly have talent.”

MD: “Ah, you see. I wish to make her an artist and a virtuoso. Ever since I relieved her of all these concerns, I have seen her develop, blossom: she has more colour.”

Jouvet-Magron: “There are not enough [63] virtuoso artists in our era.”

MD: “What we especially lack is artists who create.”

Dupré took me aside: “How is the technique coming? Tell me about your work, your impressions.” I recounted these in detail and said that I had written exercises for my personal difficulties: the heels. MD: “Ah, that’s very interesting; don’t forget to bring them to me. Difficult, huh, that old Alkan? The little fugue in A minor [No. 3]… it will do you good. Have you seen Busser?* What has he said to you?”

“Nothing, Master.”

MD: “Nothing?”

“Yes. He was astonished to see me and said to me ‘but… you have gotten fatter.’” Hilarious laughter from Jouvet-Magron; Dupré was furious:

“Can you believe it! I’ll be taking a little trip in ten days or so; that’s why I am obliged to put you on Tuesday the 26th [of August]; you’ve taken note of it? Bring me the Adagio, your technical exercises, and the A minor.”

Jouvet-Magron has a rather elderly appearance and walks with a cane. A pale blonde, she dresses in light colours, wears her hair down with a tousle of curls at the front. She observes a lot, speaks [64] little and gently; her face is delicate. She lives in Meudon.

* Classes continued in the summer during the war.

Wednesday 20 August 1941

This morning, a three-hour lesson at Meudon (9:30 to 12:30). From the garden, I could hear the organ: Dupré was working on his Prelude in A-flat.[64] From these three hours of work and conversation, here is exactly what I’ve retained:

MD: “I am working on my technique again now, because of you. It’s very interesting. I am afraid that you will catch up with me! No. On the contrary, I want you to match me and surpass me.

“What should we begin with today? To be completely honest: I am longing to hear the second movement of the symphony.” The Adagio, presented to the jury two months ago, was yet unknown to Dupré. The master followed along with the score. I was very moved.

MD: “I like that, deeply. You have made huge progress in composition, my little Jeanne. In terms of musical emotion, you have developed greatly. It’s much less harsh than what you have written at other times. One senses that, at last, you are pouring your heart out. [65] It’s grand, it’s profound; and the chords that begin each measure—expansive, well thought out—are like a conversation in which each word counts. I am very happy.

“In terms of form, however, perhaps the ending is a bit truncated; when one arrives here (the re-entry), one thinks: well now, it’s soon going to be over… For a symphony, you can allow yourself to go with more lyricism in the conclusion. And here, your orchestration will not give you the effect of alternation that you want: these contrabasses are not doubled at the octave. You can look at that again if you want.”

I showed him the letter in which [Maurice] Le Boucher proposes that I give three concerts in Montpellier in 1942. As soon as he read it, Dupré said excitedly: “That’s decent of him! You must say yes.”

We worked on pedal technique. From the first scales, Dupré has his eyes glued to the pedalboard; then: “That’s great; continue; I’ll go look.” And, returning from the back of the room: “You cannot imagine how pretty it is to see, so flexible, with your little heels. No woman organist [66] has ever played the pedals as you do, my little one; you have understood so very well.” And again: MD: “Since the last lesson, I have discussed technique a lot with Marguerite; I’ve worked and researched for you. She told me that [Nicolai] Medtner made her work on scales slowly at first, then doubled (by 2 and 4) a single time. To avoid tension when practising, try it. It’s something that only a great artist could have discovered.”

Speaking to me of his symphony “Évocation,” written for the inauguration of [the rebuilding of the organ of] St-Ouen in Rouen,[65] Dupré announced to me that he had finished the sketch of the three movements the evening before last. MD: “When the music is written, I’ll be able to breathe once more. Before looking at the last two movements again, I’m going to return to the first; there is an important inversion to make.” He feels he is ahead of schedule. In the Adagio, there are, he says, some curious timbral effects, resembling, to the ear, the use of sostenuto, an unintended parallel, but about which Dupré said to me: “I’m happy if this is the influence of my organ.”

Concerning the Prelude in A-flat, he thinks that the tempo, as published, is perhaps a bit excessive, but [67] that, even at a more moderate tempo one must understand it as agitated, tumultuous (crescendo by means of the Swell box). I played the Prelude twice.

Parting words: MD: “At present, you play the organ just as well as I. Now you have all you need: you have me, your little organ, all of Bach, the environment that you need in order to work. I want you to work happily and without pushing. For children, one uses an allegory to explain that we are tied to our planet so long as we live: a path filled with stones, thorns, and, above it all, sky. By the time of your triumph, you must have traveled a path filled with joy where people will say to you, ‘along your way, smell this flower, look at that butterfly, see this beautiful view.’

“The cultivation of your talent and the work that we will do together are just as important to me, from a pedagogical perspective, as all my students and my teaching combined. When I am gone (because I will expire like everyone else), you will be there; I am counting on you.

“I will tell you what Widor said to me, while [68] accompanying us to the train, for my first trip to America: ‘Think about what you represent.’ The prestige of France in foreign countries has been completely destroyed. We need virtuosi; everything must be rebuilt. If necessary, I will once again cross the border and play all of Bach, even in Germany!”

Thursday 21 August 1941

My little organ was installed in my studio.[66] It’s a day for celebrating an anniversary.* Yolande inaugurated the organ. Very impressive. I sent a note to M. Dupré who wanted to be notified immediately of this big event. My studio has become a temple for work.

* August 21 has become the anniversary of my collaboration with Marcel Dupré, a date that he himself proclaimed and never forgets.

Sunday 24 August 1941

At St-Sulpice, 9:00 AM. The master gave me three major organ works by Liszt, promised since January, which have just appeared in his edition. He had these kind words: “This is a little souvenir of something huge,” the dedication having been made in remembrance of my First Prize in organ.

At 4:00 PM, I took the train from St-Lazare station in the direction of Évreux where I was met by [69] Mireille Auxiètre, who had invited me to spend a week at her mother’s place in the country, nine kilometres from Évreux. I crossed Évreux, a city destroyed; the cathedral has a damaged tower.[67] Terrible feelings. We covered the nine kilometres by bicycle.

Saturday 30 August 1941