4 Jeanne Demessieux’s Diary and Letters of 1932-1940 in Translation

The surviving diary and letters of Jeanne Demessieux’s adolescent years embrace her first eight years of music study in Paris, particularly that undertaken at the Paris Conservatory, then located at 14 rue de Madrid. They do not comprise a complete account of her experiences. Indeed, most of Demessieux’s 1930s correspondence survives only as excerpts published in Une vie de luttes et de gloire by Trieu-Colleney. Moreover, Demessieux’s diary of June 1934 to September 1938 was kept only sporadically. Therefore, the following text interleaves multiple materials to portray Demessieux’s life during the period October 1932 to June 1940. These are passages that Trieu-Colleney selected from Demessieux’s letters sent to family members, complete letters to her mentors that survive as drafts, diary entries, and a selection from Demessieux’s record of organ music played for services at St-Esprit. Periods of Demessieux’s life not covered by letters or diary, but for which information is available from other primary and secondary sources (identified in endnotes), are described in intervening paragraphs in the text.

To the extent possible, materials are arranged in chronological order. Each piece of dated correspondence occurs in a shaded textbox, and is headed with its date at the left margin. Diary entries are placed in unshaded textboxes, with each entry having a centred date above it. Explanatory comments on the content of letters and diary occur in endnotes. Names of persons that are highlighted are linked to a “Register of Persons Mentioned in Jeanne Demessieux’s Diaries and Letters,” which supplies brief information concerning those who could be identified.

From letters of Jeanne Demessieux to her sister Yolande:1

11 October 1932

We arrived in Paris with the rain… Now [though,] the air is fresh, and the beautiful autumn sun is shining. My piano will arrive on Friday . . .

22 October 1932

My piano has a tremendous sound, but it is quite uncompromising. I inspected it from top to bottom and everything is in good shape.

28 October 1932

Monsieur [Lazare-]Lévy had me play my Bach, my étude, and my [other] piece, and said it was good…I owe my success mainly to you.

5 November 1932

. . . Mlle Gousseau had me play the Chopin étude, the Bach, and the Beethoven sonata… she said it was very good but that I pound too much.

[undated:]

Mademoiselle had me work on the Chopin finale in a surprising way! I was paying such close attention that I sat there with my mouth open, staring wide-eyed.

[undated:]

My piano study is going well. I’ve started to learn the Czerny toccata: very difficult. You can judge for yourself: it’s all in thirds.

27 December 1932

I’m still working on my toccata. I managed to play it at 132 to the eighth note; it’s beginning to sound like something [ça commence à compter].

1 January 1933

I know Chopin’s Impromptu No. 2 by memory, J. S. Bach in transposition and, still, the Czerny toccata. I always do an average of three and a half hours, sometimes, four.

. . . Sundays, I don’t work. Monsieur Lévy insists that I should rest on that day.

Technique is beginning to go well again. Mademoiselle Gousseau is very strict on this matter, with good reason I believe, for Monsieur Lévy is very lenient. He told Maman that he will present me [in an audition at the Conservatory] next year and that I will be received with open arms.

13 February 1933

. . . I am also composing . . .

16 March 19332

I began with Czerny’s École [du] Virtuose:3 He showed me the fingering…

“You see, Jeanne,” he said, “this fingering is going to facilitate your technique, but I don’t want you to use this in your études, because they are meant to make you work.”

Then came Bach:

“Well, there’s nothing to say about this fugue. Really, it’s perfect.”

Then the rondo-finale of Frédéric Chopin’s Concerto.4 It’s very difficult, but with Monsieur Lévy’s technique, everything becomes easy . . .

22 March 1933

Monsieur Lévy has given me the Allegro from Chopin’s Concerto… It’s so very beautiful, an architectural marvel, one could say.

We have bought a pretty collar for Kety [family cat], decorated with a bell and nametag… The first evening we put it on her, she became very agitated, the bell annoyed her so, but now she thinks nothing of it. She’s growing prettier all the time and, I believe, more mischievous.

22 May 1933

My technique is coming along: all I lack is a little stability in my fingers… a successful entrance audition to the Conservatory is in sight . . .

4 June 1933

This morning, I worked for two hours on Clementi’s Gradus5 and Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 11, and I improvised for ten minutes.

This afternoon, I’m going to work on my Lutins rondo,6 Chopin’s first étude (for an hour and a half) and, after that, if I have time, the Impromptu No. 2 (this is what I’ll play for Mademoiselle’s student recital, instead of the rondo: it will have more effect and it’s more suited to my temperament…) The Revolutionary Étude7 I’m saving because I would like to play it for you during vacation—it is so beautiful.

23 June 19338

. . . Maman had me dressed in my white dress to which she had added a Marie-Antoinette fichu tied at the back in a big bow.

I played Monsieur Lévy’s two études and my Chopin impromptu. It appears to have gone marvellously well! In attendance were Mademoiselle and her entire family; Madame Giraud-Latarse [who is] Monsieur Lévy’s former teacher and Mademoiselle [Gousseau]’s former preparatory teacher;9 and all the students’ parents. Madame Giraud is said to have been jubilant…

Maman said to me that my touch was very delicate and that the passage work was so well done that one would think it was of no difficulty. I’m as fearless as ever, and during the day before the recital I was burning with impatience.

In all likelihood, Demessieux, with her parents and grandmother, left Paris for Aigues-Mortes for at least part of July through August 1933; correspondence with her sister Yolande resumed in September.

From letters to Yolande:10

29 September 1933

The notorious passage by Liszt that I couldn’t manage, well, I worked on it for a good half-hour, and I can now play it very well . . .

11 October 1933

Every day, I go to the forest alone by bicycle; I go freewheeling down avenue Daumesnil and do two or three laps around the forest…11 then, I head back up with difficulty; you must remember that “lovely” little hill . . .

I’m yearning to take the [entrance] exam.

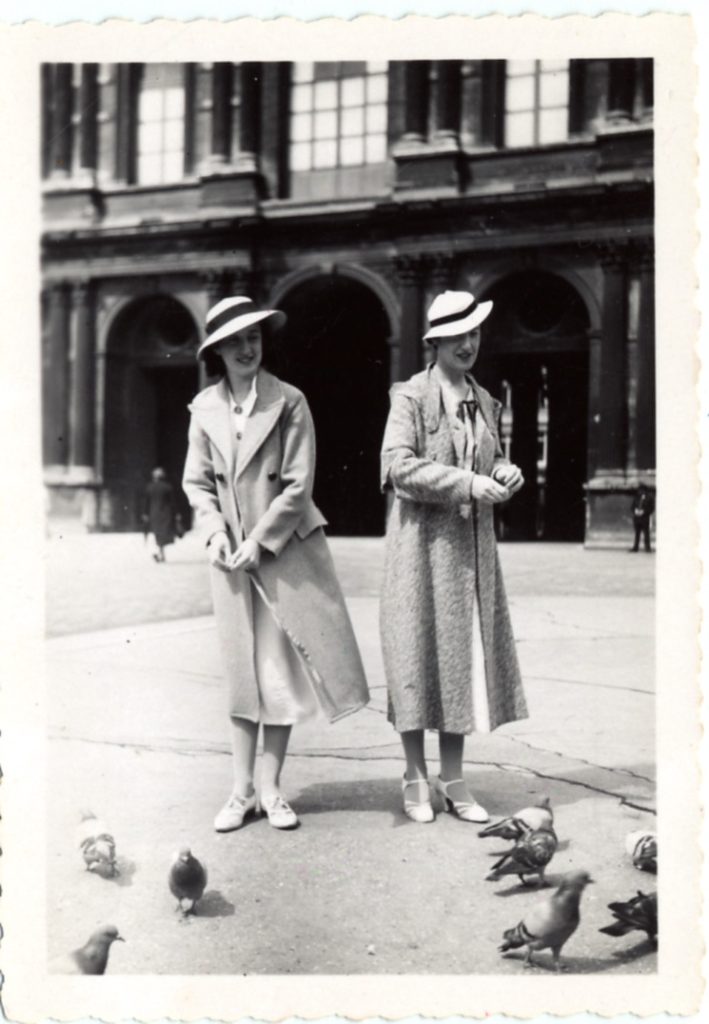

Goosen van Tuijl collection.

In autumn 1933, the start of her second year in Paris, Demessieux successfully auditioned for entrance to one of the limited number of openings in piano at the Conservatory. She was assigned to the class of Santiago Riera, not to that of Lazare-Lévy as she had hoped. Unfortunately for Demessieux, a teacher whose class was already considered complete—twelve students was the limit in the 1930s—did not have final say with regard to adding new students, particularly when there was another, in this case Riera’s, that was not complete.12

Letter-card addressed to Monsieur Demessieux at 8 rue du Docteur Goujon:13

24 November [1933]

Dear Sir,

Mr Riera has written to me that he cannot permit any other instruction for Jeanne but his own. In other words, he did not understand anything I said to him yesterday. Therefore, if he questions Jeanne, she should affirm that her relationship with me is purely friendly. The advice that I will give her must, consequently, remain confidential. As a precaution, I can no longer have her come to [the Salle] Érard, but only to my home. Embrace her for me.

With my very best regards,

Lazare-Lévy

From letters to Yolande:14

11 December 1933

Alfred Cortot is giving a series of Chopin concerts. I’m very pleased that I saved all the money given to me so that I can go and hear, next Thursday, the lecture-recital on the preludes and, on Thursday the 14th, I will hear the études for around 15 francs for standing room; after that, I don’t know if I will be able to get the money together… To tell you that he plays well doesn’t do it justice. You would think it was Chopin himself playing his works. He is a poet above all, and more so than anyone else.

. . . I am composing. I finished a waltz and am beginning a nocturne and another piece for which I haven’t decided upon a title: Berceuse or Romance?…

21 January 1934

There is a student, Maria F[otino] (Romanian)15 whom I like very much: she is gentle and reserved. When I sit beside her in class, she is friendly, which pleases me. She is also a very good musician with an extremely soft and delicate touch… She is, perhaps, twenty? But that’s not what’s important to us because she has a youthful personality.

[Concerning a waltz composed by Demessieux that she played for Lazare-Lévy, undated:]

I performed it… When I’d finished, he expressed himself thus:

“Your first theme is very pretty and reminiscent of Chopin. However, the second theme is too long and modulates to keys that are too distant; it must return to the first; the trio, likewise, is long…”

I cannot reproduce all his explanations, but he told me to study Chopin’s waltzes away from the piano, to gain inspiration from their forms. This is why I’ve been rising every morning at half-past seven and immediately getting to work. I am fascinated by the waltzes; they are inspired in their elegance; I am meticulously studying their every detail.

1 February 1934

Presently, I’m composing two nocturnes.

My criticism of Braïlowsky is that he lacks both suppleness in Chopin’s melodic passages and sensitivity for melodic line. These are precisely the two things I love about Cortot’s playing.

I am glad that Mimi is working hard,16 knowing that later on, when she is in Paris, working alone and properly, will be all right, but it’s not easy… For the time being, I know that she is in good hands.

21 February 1934

Monsieur Riera hasn’t been giving his classes lately. Monsieur Gentil has been replacing him.

This morning, [however] he reappeared… I presented the Liszt paraphrase. He was pushy with me, as usual…

“To think that she doesn’t like this masterwork! This is inconceivable!” To this, I retorted, with a smile,

“But, Master, I like it very much now!” He had nothing more to say and seemed rather embarrassed.

[Referring to Lazare-Lévy:] Dear Master! Here is someone who deserves all my regard for him and my confidence in him! He takes a great interest in my compositions and gives me bits of advice… As for my piano playing, he is very happy with the results!

14 May 1934

Sensational, magnificent, marvelous news! The first competition is set for the 31st of this month and we have three new pieces… a program that pleases me to no end…17 Exam fever has again taken hold of me. I’ve had my pieces for eight days and I know them all by heart…

I am still accompanying at church, which gives me pleasure and takes my mind off my other work. One day, at rehearsal, the priest said to us, “I am bored… bored as a chicken with a toothbrush…” I’m still laughing.18

From Demessieux’s diary entitled “Memories Impressions Diary 1934–35–36”19

Thursday 28 June 1934

I resume my daily diary with joy.20 There is so much running through my mind these days! The end-of-the-year competition took place yesterday from nine in the morning to eleven in the evening. At half-past six Maman came to wake me. I quickly dressed and, everyone else still asleep, I attached the mute [moliphone] to my piano and did my daily exercises.

Finally, it was time. I was all dressed up in my white dress and I was reminded to be passionate in the ballade.21 I responded by opening one eye and yawning my head off. When descending the stairs, I slipped, caught myself and, by an effort of will, woke up completely. I ar We arrived at the Conservatory at half-past eight. Immediately, I went to the green room. Once there, I became very reserved, as I always force myself to be as much as possible before playing. I had to wait an hour and a half before my turn.

Finally, my name was announced. I walked on stage [2] and sat at the piano. The benefit of that big long waiting period of an hour and a half was that I was able to give myself entirely to my ballade. It was for me, as always, like experiencing a long dream; it seemed to me as if all these all the feelings of this beautiful poem were being improvised by me, since they so matched my spiritual state. The last chord struck, I rose, unsteady on my feet, while a murmur rustled through the crowd. My vision was blurry but with a great effort of will I managed to walk as far as the door where several mothers were waiting for me. Then, sheltered from the curious gaze of the crowd, I allowed a long groan to escape my lips, while a cold sweat broke out on my brow and my hands. A short command: “Hold her up…”

Nevertheless, little by little I recovered my composure and was able to walk. The first face I saw, all worried, was Papa’s. He rushed to grasp me in his arms. After a moment, I was able to say,

“I played well…you know… [3] Oh! I can hardly go on... I thought I was going to faint.”

We went around the street by the Conservatory to meet up with Maman, who had not been able to get out earlier. Soon, I saw her on her way down, crying and searching for a glimpse of me. She too embraced me lovingly and I succumbed, for my legs would no longer carry me. At that same moment, the intermission began. There was a crush of people, but I felt so weak that just to move was an effort for me. My classmates were at our side; everyone hugged and congratulated me. The mothers said,

“I thought she was going to faint: she looked as pale as a corpse.”

Mr Lévy told me, straight out, his impressions:

“She will certainly win something, she played so well!”

And while he was encouraging me, my eyes searched the crowd for Mr Riera, but he didn’t show up. I wasn’t to see him until an hour later… Sensing my strength returning, I went to listen to some of the contestants, using Maman’s ticket.

At noon, arm-in-arm, we returned [4] home. After lunch, I sight-read some preludes and fugues for organ by Bach. At five PM, we went out again to the boulevard Poissonnière.22 The ballades session wasn’t over yet, which permitted Papa to make the acquaintance of Mr Labroquère, the father of a charming nineteen-year-old classmate of mine, Françoise, who is extremely musical, intelligent, and lively. The family is descended from Liszt, whom Françoise very much resembles. We are always together. Maman looked at us and smiled and described us as inseparable by dubbing us “Delacroix and Chopin.”

After this aside, I continue. I was [feeling] a little better for the sight-reading [competition]. Everything there went very well. Only after I began a long wait did my nerves start to bother me. All I could do was sit and quickly eat a sandwich, and I immediately wanted to return to the Conservatory. We met up again, talked, traded predictions; some of my friends laughed, others fretted. As for Françoise and me, we looked like two people on their deathbeds, [5] each as pale and stiff as the other. All this was happening in the green room, among friends; our parents were in the hall.

Eventually, a man came to tell us that Mr Rabaud was going to read the competition results aloud. We quietly opened the door to the hall; a deathly silence reigned. Everyone was breathless with anticipation, everyone’s lips trembled. Slowly, the director [Rabaud] announced the awards. First Prizes… Second Prizes… First Mentions… Second Mentions… finally, my name was pronounced, third in this last category. Hearing this, I tottered again, my eyes closing under the shock of such indefinable brutality; unfortunately, no one was looking after me and, if I didn’t actually fall, it was only because there was such a huge crush of people. Oh! This moment! I will remember it for a long time! Propelled by the ceaseless wave of the students around me, I passed by Mr Lévy, who was holding in his arms a poor little blonde who had fallen to bits, Mlle Berruyer, who was sobbing against his shoulder while he covered her with kisses. Then I saw Mr [6] Riera, who said to me, quite offhandedly,

“This is what the jury came to accomplish? They could have stayed home: you deserved better.” There was nothing I could say to him in response.

These two pictures, of Mr Lévy and Mr Riera, continued to dance before my eyes like ghosts: the first I’d like to think of always; the second I can only regard with a fleeting smile.

I found myself outdoors, jostled, blinded by photographers’ flashes. Amidst general high spirits, Papa and Maman soon found joined me. We heard nothing but shouting, almost like a riot. Such tears! Such sobbing! Presently we encountered Valérie Hamilton and her mother, in the throes of a terrible nervous fit.23 Their cries were very nearly demented. The entire breathless crowd, all the discordant cries, upset me to the point that I simply clung to Papa, sobbing. All I could come out with was “Let’s go!” while nervous trembling [7] shook me all over.

This attack of nerves lasted in the subway with my complete inability to speak, and at home with endless tears. It was midnight when Maman put me to bed, tucking me in like a little baby, and after her tender, maternal caresses and kisses, and those of Papa, I slept, utterly exhausted.

Never has an exam affected me so profoundly as this one…

Thursday 28 June 1934 [second entry]

A day of rest.

Friday 29 June 1934

At 11:00 AM, Maman and I went to Mlle Gousseau’s. She received us with her usual good grace and talked to us with an open heart. “So, my little Jeanne, you are satisfied with your Second Mention?”

“Oh! Yes, Mademoiselle!”

“There we go: that’s good. I’ll acknowledge, though, that you deserved a First [Mention].”

“Ah.…”

“Yes… But I prefer that it turned out as it did. Mr Lévy will now have less difficulty taking you in his class. Mr Riera remains to be convinced: that is the most difficult…”

“Oh! Mademoiselle, [8] he won’t agree!” I cried spontaneously. And I, who never weep, sensed something hot beneath my eyelids, boiling to the surface; but I immediately took control of myself and, gritting my teeth, I managed to drive away my heart’s overflowing, volatile [thoughts]. I don’t know if Mademoiselle saw this sudden jolt to my soul, but she carried on solemnly,

“Don’t worry, Jeanne… don’t think about it anymore; Mr Riera is out of the picture.” She put strong emphasis on these last words, then, turning to Maman,

“Jeanne isn’t looking well; she is too pale… which worries me.”

Maman said responded with nothing and looked at me with a sigh. After some moments of glum silence, she said,

“We are thinking of going to see Mr Lévy sometime soon; my husband must request an appointment….”

“Madame, if would you like me to telephone him, myself? It would save you the trouble of arranging the meeting.” And without even waiting for a reply, she [9] picked up the telephone and asked to be connected. After a moment, a familiar voice could be heard through the ebony headset and Mademoiselle, putting on her pleasant smile, responded,

“Good day, Master… How are you? Oh! How amusing!… Well, here it is: I have with me Jeanne Demessieux who would like to know when she might come, with her father and mother, to visit you… Fine… Tomorrow at half-past three. Jeanne,” she said, looking in my direction. “Goodbye, Master; I shall write to you.”

Then she came and sat beside me, took my hands, and said,

“You must promise me to be sensible… Meaning that I want you to stop thinking about Mr Riera and be cheerful. It’s your age, my dear… If you remain sad, you will become seriously ill, and we don’t want that. So, it’s a promise?…”

“… Yes… Mademoiselle…”

“My poor dear! It’s hard at thirteen! But, it has to be.”

It has to be! Or so they say.

[10] Thursday 5 July 1934

This morning I went out with Papa. We went to the Vincennes Forest,24 where I did my reading. This afternoon I did my piano practice.

What a day it was! During the entire afternoon, I could not concentrate on anything for five minutes at a time. Oh, longed-for summer vacation, are you coming soon? I wish it were tomorrow: I want to see Yoyo [Yolande] right away. Oh! Such joy! The sweetest I can ever know!… I feel as if I will die waiting, while my regard for her only grows stronger. Nevertheless, were I suddenly to find her, at this very moment, in front of me, I would probably not be able to think of what to say, even to her.

Saturday 7 July 1934

Only five days to go before we are all reunited. What happiness! I’ve begun counting the days and even the hours. God grant us the joy of being able to hear, embrace, and speak to her…! So many things to tell us! I think I cannot bring a quarter of them to mind. [11]

Montpellier Municipal Archives, 4S20, Fonds Jeanne Demessieux.

I’m composing music regularly these days, generally from 1:30 to 2 PM, a time that takes nothing from my work at the piano because I only start playing at 2 PM. This past winter, I mostly composed in the evening, after supper, but Maman forbade this because it made me too tired. Having to find another time, I had chosen seven to eight in the morning at the first glimmer of pale, winter sun behind my closed shutters.

But Maman put a stop to that too because I got one cold after another; therefore, afternoon is now my time.

Sunday 8 July 1934

This morning, I accompanied both Masses, at 10:00 and at 11:30. This was the last time before summer vacation… Next Sunday, we will hear Mass at the Church of the Sablons in Aigues-Mortes. At a quarter to six I went to Benediction25 in the big crypt of [12] St-Esprit church. It is made entirely of cement, and footsteps resonate as if in a tomb.26

Demessieux made no diary entries during her 1934 summer vacation in Aigues-Mortes. By the end of September, she and her parents had returned to Paris, and her correspondence with her sister Yolande resumed.

From a letter to Yolande:27

30 September 1934

. . . It’s good to have my piano again! As soon as Mass was over, I went and played until noon. What a warm and vibrant sonority! There is no other instrument like it.

Tomorrow I will begin diligently working five hours a day again, no question. I’m longing to return to my habits. I have the courage and the will… Just practising piano is sufficient for me to want nothing else.

In November 1934, Demessieux began private harmony lessons with Noël Gallon in preparation for the competitive entrance exam to a Paris Conservatory class in that subject.28 She did not write in her diary again until January of that academic year.29

Thursday 31 January 1935

Long after the end of summer vacation, I have, at last, returned to my diary. The time for mental turmoil has passed, I suppose. In every respect, the [academic] year began well, except for the disappointment of Mr Lévy’s final response that it is impossible for him to admit me to his class without causing me serious harm. I am, therefore, resigned to this. I’ve worked hard, even righteously, on the anger in my heart and hope in my mind. Hope! Anger! Truly two things made to please me. I have never so well savoured the truth of two words, the terrible truth. Anger? Yes. Suppressed anger, a monstrous ocean against a hard rock; sadness—smothered yet boiling, steaming—that must not be allowed to escape. Hope?… [14] A poor thread of silk, the work of a spider who, firmly believing it safe, cast it out into space and attached it to the petals of a thought and the heart of a thistle. The wind blows. The situation is critical. But do not groan, oppressed soul; always stifle your protests, for the echoes would be too loud!

From a letter to Yolande:30

16 February 1935

. . . In harmony, I’ve begun dominant sevenths . . . I’ve hardly any time now for composing, and this breaks my heart… It seems to me that I’m no longer good at anything, even when I do my homework perfectly. Academic work so little resembles the ideal that I have the impression the goal is getting further and further away…

10 April 1935

The eve of a happy day. Tomorrow, a recital by Mr Riera’s students in the Conservatory Hall.31 I will play the first part of Schumann’s Fantasie [Op. 17]. A sublime piece; incomprehensible or revealing. I am, as always, very calm.

From a letter to Yolande:32

16 April 1935

The recital went very well.

11 May 1935

Time passes quickly… What is reality one day becomes but a memory the next. The competitions are upon us. For all students, they loom as something dangerous, arduous, even treacherous; I, on the other hand, see them as having one justification, merit [15] won rewarded, and one day, I’ll be free!

Oh! Freedom! Kind friend! One day (can it be true!) you will introduce yourself to me for the first time, you will take me in your arms, and I will have only to respond to your call! Oh, yes, most certainly: it cannot be otherwise. I have believed I would be meeting you for several days now, since the day when (God forgive me!) I took vengeance!… Yet, took vengeance with justice and bravura.

Yesterday I went to class with a strong feeling of foreboding. Let us take note. Before entering the class, we were waiting for Mr Riera (or, rather, just Riera) in the large second floor corridor. My classmates were merry; they were laughing. Riera arrived, in a bad mood. First, we received a whopping outburst; [16] it seems this gentleman believed himself in a henhouse, which truly upset us. We entered and the class commenced or, rather, recommenced. First, we played the Debussy étude. Abusive words, curses, with no attempt to avoid being offensive. Seated, as usual, near Françoise, I felt depressed. My heart was heavy: I can almost still feel the sensation! But I was distracted [in the clouds] and my inner nature dissolved, merged into a burning tear. Suddenly: “Her!”: as injurious a sound to my ears as an alarm bell. Awakened with a jump from my sad reverie, I slowly raised my head, and my ears could hear sounds of anger.

“Yes! Her, the one who’s been day-dreaming over there: the last time [too] she [17] stood there (sniggering) with no pencil to mark the fingering I indicated; doubtless, she is already an expert! (furious). She listens to nothing; no, you are undisciplined, you know it all too well,” and eternal jealousy, in his most bitter cruelty, showed in his eyes, his words, and his gestures.

Indignant that he would dare speak such a lie to my face and before my classmates, I leapt up and, clenching my fist almost to the point of breaking a bone, I threw these words back at him, with a look of fire:

“Even so!!… I have marked my fingerings; you’ve seen them for yourself!” I sat back down again, trembling with anger for the first time, and I added, under my breath, but with a hiss, “And besides, I’ve had enough of this!”

[18] My classmates, silent with fear, lowered their heads; thus I was able, with ease and haughtiness, to stare at that deceitful face, which, moreover, was quick to turn its eyes from the powerful and genuine sight of that was the object of his hatred. Pushed to breaking point, I had to step into the corridor for a moment to regain my composure. When I returned to the class, I was met by a frosty look, everything had changed… Even Françoise avoided my eyes: I was alone…

From a letter to Yolande:33

21 May 1935

I’m in the middle of exams and competitions; the pieces please me very much and Monsieur Lévy, Monsieur Gallon, and Mademoiselle Gousseau are agreed… I’m on the way to playing an excellent exam. My goal for the year would be to be awarded a Second Prize [in the women’s piano competition].

26 May 1935

Can inner dramas be commented upon? Yesterday, I was the fitting object of one of these dramas.

2 June 1935

I am having bouts of desperate sadness… My heart is always weeping bleeding. My only confidant is my piano. When I speak to it, [19] it understands and it tells me so; I am immediately soothed, but not consoled. Nowadays, everyone shuns me; is this a coincidence?… I am alone.

Sometimes I would like to take over the world, but I immediately have the opposing wish to close myself in and be impenetrable.

10 June 1935

Why are there, in my nature, two opposing personalities…? On the one side, passion [violence], on the other, painful or overwhelming sadness. There are days when powerful reality discourages and exhausts me, and others where indignation intoxicates me to the point of being wild.

I have the impression of not living or, rather, of living in exile.

[20] [Diary blank page.]

On June 26, 1935, Demessieux was among the youngest of 49 candidates entered in the piano competition for women. The test piece that year was the first movement of Beethoven’s Sonata in C minor, Op. 111. She received a First Mention (last in a list of ten), improving upon her standing in the 1934 competition, though not reaching her goal of a Second Prize.34

Most of July through September was likely spent in Aigues-Mortes—time away from Santiago Riera and the pressures of competing with students significantly older than herself. Diary entries and surviving letters resumed only with the new academic year in October 1935. A long letter from Jeanne’s mother to Yolande, with postscript by Jeanne, translated in full below, reveals that in Paris she continued her general studies (apparently home-schooled by her father) and went on occasional outings.

Letter from Madeleine Demessieux to her daughter Yolande, with postscript by Jeanne Demessieux:35

Paris, 20 October 1935

Dearest Yoyo,

It is I, again, who am assigned the pleasant task of writing to you. They send you warm embraces, and of course I’m referring to Papa and Jeanne. They left immediately after dinner for “Père Lachaise” [cemetery] to visit Chopin’s tomb;36 it was impossible last Thursday to find a minute and we put it off until Sunday. It was drizzling, but nothing holds Jeanne back; they went by bicycle. Today at High Mass and at 11:30, one improvisation, the march by Boëllmann,37 the toccata, and some Franck. Father Emering presided; he rushed to disrobe and climb to the gallery to thank your sister for having truly spoiled him. So there you go, you are all caught up for today.

Last Sunday [Jeanne] walked to the Gravelle plateau with the girls’ choir; these young ladies took photos “that we will send you if you wish,” and let’s not even mention fatigue, these choristers were hardly able to remain standing to sing Vespers.

The week passed as usual, with classes, studying, and lessons. Mr [Noël] Gallon thanks you for the gracious greetings you asked me to deliver on your behalf; lessons with him are going very well. Mademoiselle [Gousseau] was happy, Monday, with the Chopin sonata [in B-flat minor]:38 Jeanne is progressing in strength. From now on, all the Saturday classes will be for exercises, four Czerny études, a Bach prelude and fugue, which will make three classes per week, in addition to her being at the piano [each morning] at 8:00.

Yesterday, she studied for eight hours, did a harmony assignment, and practiced her singing after supper. There! I think I’ve told you everything and forgotten nothing.

And now to Papa, who spends his time travelling around a 100-km area to promote his own wine; in other words, he intends to buy our wine from Mr Mézy39 and sell it himself, which will net him 10 [francs per] hectolitre.40 It’s not much, but no matter, it distracts him and keeps him active. As he was saying this morning, the profits cannot be seen right away because of the purchase of the casks, but a year from now we will see the profits, and since it is impossible to draw off one-third of the harvest, we have to find another way to manage. Remains to be seen if he will have good clients. The wine is given away in Paris and Papa cannot sell it for less than 1 [franc] 60 [centimes] per litre, which makes 160 [francs] per hectolitre. He is taking on all the costs that come up: transportation, management, delivery of full casks and collection of empties, a total as I told you of 10 [francs] of profit for him and 10 [francs] per hectolitre to Mézy for casking and shipping, cleaning the returned casks, etc. They are agreed. The catch is that the order of casks, this advance, cuts into the profits for a short while. Never mind that, nothing ventured, nothing gained.

Mr Auxiètre never requested to see Papa, absolute fiction; do not plead with his brother any longer and let him say what he will.

Thank you for your kind letter. Jeanne had a good laugh over your story.

Have you been to see Mr Le Boucher? You must leave a token and repay him for having visited you. Send some flowers for Mme Mellot-Joubert and tell her that the dentist in Aigues-Mortes is looking for a manager so he can go complete his studies in Marseille. She must simply work it out with Mr Armingaud of rue Pasteur in A[igues]-M[ortes] or Grand rue Centre dentaire in Nîmes. (In case it interests her son.) Add our good wishes.

Friendly regards to Mme d’Espéries, an affectionate hello to Mme Cathata. For you my dear girl, sweetest kisses from your Maman who loves you.

Granny [Gramt],41 Papa, Jeanne send loving embraces.

Postscript in Jeanne’s handwriting:

Dear Yoyo,

We’re back from Père Lachaise, a bit tired, but that’s not important. As soon as I got home, I plunged into reading Hernani [drama by Victor Hugo], and now I’ve also finished [Victor Hugo’s tragic drama] Ruy Blas.

I see that Maman has enlightened you about my work. Don’t throw your hands up [in despair]; you know that when I want something, I insist on it. Moreover, I’ve made up my mind.

With fond embraces, dear sister.

Don’t scold me.

See you soon.

Your loving poppet,

Nanon

From a letter to Yolande:42

23 October 1935

A new development! I’ll be entering an ensemble class, that is to say, chamber music. It’s compulsory once one has a First Mention.

I’ll be with Mr Max d’Olonne, an excellent musician… I’m overjoyed.

On Monday I presented three of my pieces to Mademoiselle, two of which were composed at Aigues-Mortes and the other was finished two hours before my lesson.

… She said that I’d made astonishing progress… and that she found the Chopinesque influence to be almost undetectable; rather, there was a lot more power in the expression.

[21] 27 October 1935

It is now more than a month since I left the countryside where, ever since my childhood, I have spent my months of vacation, between the poetry of the region where I was born and the joy in this that floods my heart.

My homeland is so beautiful!

How moving are the things of which one has been deprived, this air whose salt makes the nostrils quiver, this wind whose touch is as sweet as a mother’s caress of one’s hair! Provence, Camargue! Languedoc!… These names conjure up for me a single intimate scene whose image is engraved in my memory. A great avenue of plane trees at whose feet wild grass pushes up, filled with crickets and dragonflies. The path is strewn with [22] gravel.

That autumn was a busy one for the fourteen-year-old Demessieux: as well as resuming her role as organist of St-Esprit and preparing chamber works for d’Ollone’s class, she took lessons in piano technique with Gousseau and worked furiously for the piano class of Santiago Riera. Her father, Étienne Demessieux, was away from the Paris home for a time, perhaps in connection with his wine business.

From a letter by Demessieux to her father:43

17 November 1935

I have a program of ten pieces, of which four remain to be—tackled. When I am in class, and another student is playing, I suffer from a violent desire to push him out of the way and take his place to play “with fire.” You see, I’m from the land of the sun.

From letters to Yolande:44

1 December 1935

I may possibly start teaching. You find this surprising… But consider, I’m fifteen, and it’s impossible for me to continue as I am, contributing nothing [to the family income]. Thus, it’s decided . . .45

The class with Max d’Olonne is going well. He’s given me Fauré’s [Piano] Quartet No. 1 in C minor [Op. 15] to work on.

16 December 1935

Saturday, I went to an Orchestre Colonne concert with Maman. They played Paul Paray’s Mass for Jeanne d’Arc46 and [Beethoven’s] Symphony No. 9. The mass is splendid, a true masterwork: vibrant, with wide-ranging ideas, while remaining classical in style. As for the symphony, upon hearing it again, I am again convinced that there is nothing more beautiful.47 I prefer hearing the Ninth Symphony under these conditions48 than La Juive 49 from a centre box seat…

2 February 1936

Certainly!… for the festivals… everything went very well! Here too; the notorious [setting of] Vespers of which I spoke, and that frightened me so, went marvellously. I’ve studied some Gregorian [chant], and today I’m going to accompany Vespers from the book of plainchant…

29 March 1936

Organ—We rehearsed Franck’s Psalm 15050 for Easter. For a solo organ piece, I worked on the Choral No. 3… It’s so beautiful that I never tire of playing it.

At the moment, my only piano works are Chopin’s Polonaise in F-sharp minor and Saint-Saëns’s Concerto No. 2. I have them memorized.

29 May 1936

I took the exam around half-past eleven this morning. They had me play the Chopin nocturne in its entirety and half of the Liszt étude…51 I played as you know your little sister plays.

… I’ve been admitted [to the 1936 Piano Competition] . . . It appears that Monsieur Lévy talked with Mademoiselle after my recital… It would appear that he said, “She has extraordinary technique. By next year she will be fantastic and will have everyone talking about her.”

In the 1936 women’s piano competition, Demessieux was number 35 of 51 candidates. The test piece was Chopin’s Third Scherzo. To her great distress, Demessieux failed to better her standing over the previous year’s First Mention, resulting in no prize or mention.52

Demessieux seems not to have gone to Aigues-Mortes for the 1936 summer vacation: a phrase from a July 15, 1937 letter to Yolande signals that she had not been to Aigues-Mortes for two years. Instead, she saw her sister when Yolande visited Paris in the late summer of 1936.

Montpellier Municipal Archives, 4S20, Fonds Jeanne Demessieux.

6 September 1936

There are some hours that, as they fall one by one, resonate like raindrops; others are like an immense sunbeam that strikes suddenly, splendidly, upon clouds or earth, as over in Provence. The rest are but the tolling of a bell.

Yesterday, I was with my sister at l’Étoile;53 the crowd was dense. We were all waiting for a colonial delegation coming to honour the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Perched on a stone bench beneath the Arc de Triomphe, we saw the arrival, with flags waving, of twenty or so colonial soldiers, and some French soldiers. Certainly, there was no “production,” but [23] a single prop, a flag. At least, this is what was said by the few foreigners, some Bolsheviks, who had slipped into the crowd. The French flag passed in front us; men removed their hats to salute our homeland.

Without a doubt, these were former soldiers and elderly patriots, for they were sincere. But, at this moment a wave of pride rippled through the crowd and some arms were raised with hands outstretched in a gesture that seemed to me like a supreme and solemn oath. Suddenly, a great desire to raise my arm, to swear to France the patriotism of a French heart, reach out my hand to protect the flag: such a desire leapt in my spirit. But I immediately took control of myself. Can one [24] know what is true and isn’t, what one can do and what one shouldn’t? Perhaps this gesture, like all the others, is cursed [maudit]. Why is it possible for a man to act against his will? Weakness, always, even among the strongest.

20 September 1936

Dreary weather; Paris is coming to life again. My greatest happiness is to see evening fall, this new twilight that resembles a winter twilight.

Soon, the summer vacation will be over. My sister will leave, and I will return to work. Were it not for being separated, I would wish this moment already arrived.

No diary pages survive for the 1936–1937 academic year or for the remainder of the calendar year 1937. First-person accounts consist of letters from which Trieu-Colleney recorded excerpts giving brief details of Demessieux’s studies. Trieu-Colleney quotes at length, however, from a letter describing an event that occurred on October 8, 1936—a visit to Marcel Dupré’s home. This was undertaken on the advice and recommendation of Montpellier Conservatory director Maurice Le Boucher: he suggested to the Demessieux family that after completing her study of piano and harmony their young daughter should study organ with Marcel Dupré.54

From a letter to Yolande:55

8 October 1936

This Thursday morning… Maman and I went to Marcel Dupré’s home.56 How… to summarize in a few words this unforgettable meeting that lasted an hour and forty minutes?

… First, he asked me to go to the piano. I played the beginning of Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 106 for him, which I was very pleased to know now by heart—then, upon his request—“Vision” and the “Feux follets.”57 My playing pleased him… he was very moved… He said that he found himself in the presence of a case of the highest order and that this interested him immensely… He asked me about everything I’d done since the age of three and made detailed notes of everything. When I got as far as saying that I’d been awarded a Second Mention, then a First Mention… and then [in the 1936 composition competition], nothing, he looked at me… he started to weep… After that, he asked me how many pieces I’ve composed… Then, he had me go to the organ. What an organ!… I played Bach’s Fantasy… then he gave me a written theme to improvise upon . . .

I improvised like a dream . . .

He ended the session by saying, “From this point onward, I am taking this child under my artistic protection.”

How beautiful it is at his home! A real palace, with a recital hall for organ and piano.

As a result of this audition, Demessieux received private instruction in organ and improvisation from Dupré over a period of two years.58 Also in October 1936, Demessieux became one of twelve students in Jean Gallon’s Paris Conservatory harmony class, following a competitive examination for a limited number of places.

From letters to Yolande:59

22 November 1936

My work is, indeed, going well. But this is not without pain. I have bounced from one class to another. Some days, I leave home at half-past seven in the morning and do not return until eight in the evening.

Right now, for piano, I’m working on two of Liszt’s Transcendental Études, “Vision” and “Chasse sauvage,” Beethoven’s Sonata, Op. 106 (all four movements), Liszt’s Spanish Rhapsody (which I’m working up again for an audition in December), Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue, some Chopin études, Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 6…

6 February 1937

. . . My lesson [with Marcel Dupré at his home in Meudon] went very well. It appears I have made immense progress. I have a lot of work to do because in two lessons I must complete the [organ] method,60 after which we will begin on improvisation… in two weeks I must play J. S. Bach’s Trio Sonata [No. 1 for organ] in E-flat for him, from memory.

The piano class, at the moment, is close to being a triumphant success . . .

14 February 1937

. . . In truth, I think my joy is indescribable… Oh how happy am I! I can say nothing more.

This morning, Lazare-Lévy was horrified by the thought of the work I put in every day, but, when he heard me play…! I am very happy. In the harmony class, Jean Gallon was delighted; he loaned me the Honour Book as a token of favor.

18 April 1937

The third school term clearly seems to serve no purpose here; exams and competitions are already scheduled, and everyone has worked so hard that it’s all just a matter of whether we will have enough time to sit for them.

At the piano, I’m battling with Baïlakirev’s Islamey.61

Braïlowsky is giving a Chopin recital on the 23rd. Among other works, he will play the preludes. If I can go to hear this, I won’t miss it . . .

We are merrier than ever . . . [Am] following the advice of Jean Gallon.

Excerpt from Demessieux’s record of organ music played at St-Esprit, May 16, 1937:62

| Feast of Pentecost | ||

| — High Mass — | ||

| Entrance: | Fantasy in G minor | -Bach |

| Offertory: | Fugue in G major | -Bach |

| —Improvisations on liturgical themes— | ||

| Recessional: | Toccata and Fugue in D minor | -Bach

|

| — 11:30 AM Mass — | ||

| Entrance: | [Trio] Sonata No. 1, Finale | -Bach |

| Offertory: | [Trio] Sonata No. 1, Allegro | -Bach |

| Recessional: | Chorale | -Mendelssohn |

| — Vespers — | ||

| Entrance: | Chorale from the Suite Gothique | -Boëllmann |

| —Improvisations— | ||

| — Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament — | ||

| Sortie: | Toccata | -Boëllmann |

In a letter to Yolande, probably from June or July, Demessieux described the evening of the 1937 harmony competition:63

Demessieux, after just one year in a harmony class, received a First Prize.64 This qualified the sixteen-year-old Jeanne for the privilege thereafter of admission to Rome Prize competitions at the French Institute.65 It also made her eligible to join a counterpoint and fugue class in the autumn of 1937.

Now in her fourth year in Riera’s piano class, Demessieux performed, at the June 3, 1937 piano exam, works of Chopin and Saint-Saëns. She received a “Quite Good,” qualifying her for that year’s competition.66

Meanwhile, Riera at 70 was due to retire that year. Demessieux would arguably have been delighted when her father received a communication from Riera’s designated successor, concert pianist Madga Tagliaferro:

Telegram addressed to Demessieux at 8 rue Dr Goujon and stamped as received at 168 avenue Daumesnil at 16:25–22–6–1937:67

Garches68

Unless otherwise instructed: I will be waiting for your daughter on Thursday 24 at 6:30 PM at Maison Gaveau, 45 rue La Boétie.69

Best wishes,

Magda Tagliaferro

In the women’s piano competition of June 29, 1937, Demessieux was one of 45 candidates. The test piece was the Allegro from Saint-Saëns’ Piano Concerto No. 3, and Demessieux bettered her standing from that of 1936 by receiving a Second Prize.70

When competitions were all concluded and Demessieux was able to extricate herself from her commitments at St-Esprit, she could finally look forward to leaving Paris for several weeks of vacation.

From a letter to Yolande:71

15 July 1937

What wonderful holidays we are going to have, it having been two years since I’ve seen Aigues-Mortes! I’m burning with anticipation of our departure.

While on vacation in Aigues-Mortes, Demessieux continued composing by writing a song, “Le Moulin,” for soprano and piano, with poetry by Jeanne Marvig.72 A working copy of the score, signed and dated Aigues-Mortes, Aug. 10, 1937, includes hastily penciled indications of an orchestration.73

No letters or diary pages survive from the academic year 1937–1938. In autumn 1937, Demessieux resumed participation in the chamber music class taught by d’Ollone, and in the piano class, now taught by Magda Tagliaferro.74 The Conservatory had two classes in counterpoint and fugue, one taught by Simone Plé-Caussade and the other by Demessieux’s private harmony teacher, Noël Gallon.

Whether fortuitously, or because of someone’s design, there was a place for Demessieux in Gallon’s counterpoint class.75 In the fugue competition at the end of the academic year, Dupré and Messiaen were among the composers on the jury.76 Demessieux was one of those recognized, receiving a Second Mention.77

Montpellier Municipal Archives, 4S20, Fonds Jeanne Demessieux.

For her performance of works by Mozart and Saint-Saëns at the June 2, 1938 piano exam, Demessieux received a “Not Bad” (“PM” for Pas Mal) and admission to that year’s women’s piano competition.78 Competing for the fifth time on June 29, 1938, she was one of 53 pianists in the competition.79 With the test piece being Chopin’s Fantaisie, Demessieux achieved her goal of a First Prize in piano. Moreover, in the published list of laureates, Demessieux’s name was second of nine who received a First Prize, doing credit to Magda Tagliaferro.80

During a month spent in Aigues-Mortes that summer, Demessieux wrote friendly letters to Tagliaferro and her other mentors, corresponded with a Paris impresario concerning a possible audition in Paris, and negotiated her return to duties at St-Esprit. At the end of her summer vacation, she made one long, retrospective diary entry while on a train from the Midi to Paris.

[25] Some events and memories of July 16–August 16, 193881

[Written] on a train on August 16th. Arrived in Aigues-Mortes on July 16th, a Sunday, at six in the evening, in splendid weather. We had left Paris together the previous evening, and arrived Sunday morning at Nîmes, where we heard Mass at Saint— to the sound of a badly tuned organ, in a very pious atmosphere. Upon leaving the Mass the church, we visited the Roman baths and the Fountain Gardens.82

Very happy, my first day at Aigues-Mortes, but without being fully aware of this good fortune. During the night between Monday and Tuesday, Yolande fell ill with pneumonia, followed, some days later, by pleurisy. So unfortunate!

As quickly as possible, a curative regimen of work was established for me. I was finishing my sacred cantata.83 Every evening, a solitary walk along the path from Grau84 as far as [Étang] Perrier [de la Ville] to see the sunset. Unique impressions. Three weeks later, my sister’s condition having improved, she wanted me to go by [26] bicycle with Papa to Grau. The sea! Raging, with foam-capped waves. We went to the far end of the pier, and stood on the breakwater, where we collected some crabs to take back. We returned twice. [T]he fourth time, I had advanced alone towards the wild, open sea. I experienced a sensation of tremendous terror faced with a succession of waves, that seemed to be trying to pull me into their depths and before this vastness, [this] image of God, that I imagined as a child was the “supreme being,” here on Earth, in His likeness, and which, to me, represents an allegory of the symphony.

During the first three weeks, I worked on orchestration for the very first time and wrote to Noël Gallon and his wife, and to Magda Tagliaferro.

I received a letter from the impresario Alfred Lyon asking me for an interview.

Draft of a letter from Demessieux to Noël Gallon and Madame Gallon:85

19 July 1938

Dear Master, dear Madam,

Here I am, the day following my arrival in the Midi. My first thoughts are for directed towards you; be assured that if words could express it, all my affection could be read from this my letter. But no more in my letter than in the words But I prefer not to know that I no longer have need of polite formulas: your generosity is too sincere and it would be for me to fully return give back so little.

I wish to tell you how good I feel just being here Since my arrival, I’ve had a sense of well-being, of relaxation that is truly restful. This lifestyle change is so sudden I am going to take advantage of this as much as I can, in all possible ways because! I would like to be able to compose for a month. Do you think it would be dangerous to not write any fugues for a month? Mlle [Paule] Maurice has offered to correspond with me: I am to send her drafts of the choral movements when and as I’ve worked on them. [Left margin insertion:] I’ve accepted because I am [the offer] bit by bit because it pleases me to prepare myself for the composition class. When I return [to Paris], I will show you my masterpieces, one of which is not yet finished I will hold back from critique in order that you may see it, Master, with all its flaws, and to tell me face to face, and so that you are the first to tell me the whole truth…

With all my heart I wish you a happy summer vacation and good heath, as well as for Mme Espinasse. Yesterday morning I visited Nîmes, a city I had until now too quickly toured. My sister Yolande was not too overcome by the voyage; we hope that the change in climate will heal her completely. I would be very pleased if you would respectfully remember me to her.*

My parents and my sister Yolande have tasked me with expressing to you their most sincere friendship and all the plea the joy they will have will feel at seeing you again in August.

My letter is not very long

* I’d have liked to write you a longer letter but am lacking subjects! Perhaps I could give you an sense idea of the atmosphere ambiance where I am by telling you that the song of cicadas drowns out the noise never ceases, that it is impossible to stay out in the sun, and that the wind blows as freely as can be across the plains! I envy it and I am going to try to do as to borrow its ideas… Excuse my chatter; if I wasn’t certain it could but I think it pleases you, I would not write concerning these trifles that are so important to me.

Draft of a letter from Demessieux in Aigues-Mortes to Alfred Lyon, a Paris concert agent:86

22 July 1938

Monsieur,

I have just received your letter of the 19th. It is with a pleasure that I will come to you as requested I agree to a the meeting with you you have asked of me, but it is unfortunate that I am unable impossible for me to grant it to you accept this opportunity at present. I am presently on holiday in the Midi and must return to Paris around August 20th. If this is not inconvenient for you, I will let you know by telephone telephone you upon my arrival which day is convenient for me to set a date.

Meanwhile In the meantime, I pray you please accept, Sir, my respectful regards.

J. D.

Draft of a letter from Demessieux without salutation or date, perhaps to Magda Tagliaferro:87

Draft of a letter from Demessieux in Aigues-Mortes to Magda Tagliaferro:88

21 July 1938

Dear Madam,

Here I am in my dear land of cicadas and heat. I am writing from a land far removed from yours. I think that as I write to you we are must be quite far apart at present! I still feel I am barely escaping the sensation I had during your [concert] tour last January… but here nature is gifted with such power but here the decor and surroundings are countryside here is more comforting than the thought that of our class when you were not there, the dear countryside that surrounds me too and it is what is even more comforting is the wish that I am making with all my heart that the summer vacation permits you fu[ll] complete respite from the strains and stresses of the year. You will be happy to note the sense of well-being I have here. Here, it’s the And then I have the luxury of thinking You will be happy to note the sense of well-being I have here; the sudden calm that surrounds me and the complete change in my habits make me the life I lead, amidst a familiar and well-loved countryside liberates my spirit from all the quaint things accumulated there!89 The sea is five kilometres away; we go by bicycle under a burning sun in a heat nothing like the evening; it’s a great pleasure magnificent feeling to return while contemplating the at the setting of the sun. What pleasure it is to bring to mind L’Isle joyeuse!90 Everything contributes to the sensation of beauty. I have access to a piano and to an isolated pavilion for composing from which the horizon extends as far as the eye can see and in which I compose. I am writing to you from there.

I suggested to Mr Le Boucher the program that we had adopted for the Montpellier concert; I still haven’t had a response after two weeks. I think that looking forward to this concert will be very beneficial for me; it will make up for the training in the class that I will so dearly miss next year… What more may I say something else? That I think of you every day and that I would write this to you again if you don’t mind, I will again tell you this in writing again.

Draft of a letter from Demessieux in Aigues-Mortes to Magda Tagliaferro:91

22 July 1938

Dear Madam,

I have just received a am sending you a copy of the letter I just received from the office of concert agent Alfred Lyon. I’ve replied by accepting the proposed meeting, but only following my return to Paris on August 20, which is set for August 20th. I do not want to get involved in anything without your advice am writing to ask your advice because I do not wish to become involved in anything whatsoever without your consent.* I believe that I’ve told you my wishes plans for the future; it would be a joy to be guided by you at the start of the my career. If I could hope to achieve this I could happiness of seeing realized if, however, I could can see my wishes realized.** Please forgive the liberties I am taking and believe with feeling I pray you believe, dear Madam, in my deepest appreciation and I send you my most affectionate greetings.

* When I remember how not along ago I said to you not to concern yourself with your students! I am justifying the opposite at a time when you should not be thinking about us I wish you rest.**

Draft of a letter from Demessieux in Aigues-Mortes to Monsieur d’Argœuves, choirmaster of St-Esprit:92

1 August 1938

Monsieur d’Argœuves,

We are going through something as painful as it is unexpected: my sister has been ailing since the beginning of our vacation here. First, she had pneumonia, which led to pleurisy. I foresee it being difficult for us to return to Paris in two weeks! You can imagine how this troubles me. For now, and before making a decision, I would like to ask you a question: is it possible, without too much difficulty, to replace me, only for the two weeks? Someone would need to play the Sunday services and the occasional services. Can you give me an immediate response? I will be very grateful to you for also telling me whether Father [de la Motte] is presently in Paris. I’m so terribly sorry to be obliged to ask all this of you and apologize for assuming taking this liberty. I trust that our friendship justifies these.

With my best wishes,

Draft of a letter from Demessieux in Aigues-Mortes to Father de la Motte, parish priest of St-Esprit:93

8 August 1938

Father,

I have sad news to share with you: my sister has been ill since the start of our visit here. She was first afflicted with pneumonia that the consequences of which led to pleurisy. She has been bedridden for exactly three weeks, and it is impossible to imagine her return to Paris for several months; so that is the situation. Before discussing another subject with you I ask with faith that you think of her in your prayers.

I wrote some days ago to Mr d’Argœuves to enquire in case it is necessary to that I be replaced for a time due to illne[ss]; you must already know this… But, having received Mr d’Argœuves’s response, I realize that, despite the dedication he shows, this solution poses difficulties. So, I’ve decided to resume my duties at Saint-Esprit on August 17th. I will return to Paris with my grandmother94 while my parents remain near my sister, whom they cannot possibly leave. If there are services to be played on the mornings of the 16th and 17th, it is confirmed that Mr d’Argœuves will look after these.

With my sincere respect and devotion, Father,

Draft of a letter from Demessieux in Aigues-Mortes to d’Argœuves:95

8 August 1938

Monsieur d’Argœuves,

I thank you, with my whole heart for having looked after the information you gave me and apologize again for any trouble that I’ve given you.* Here is the solution we’ve envisioned: in all likelihood, my sister’s illness will oblige her to prolong her stay in the south of France until the end of the vacation period; my parents, unable to leave her [here] alone, will stay as long as necessary while I go back to Paris with my grandmother. Given this arrangement, there is no reason compelling me to remain here. I’ve decided that I will be in Paris on August 17th. If there are any services that day in the morning, it is better that you not count on me, but I can take any services in the afternoon. Since I will not have the pleasure of seeing you before your departure, I wish you, from this moment on, a very good vacation and the rest you must be looking forward to enjoying! My family sends their best wishes.

With all sincerity, Mr d’Argœuves,

* I also understand fully the difficulty of replacing me for all services during vacation time.

Draft of a letter from Demessieux in Aigues-Mortes to Magda Tagliaferro:96

11 August 1938

Dear Madam,

Before My warm sincerest thanks for the advice you have given me. I now understand the situation and will take serious action in the ways you have proposed indicated to me. When I have news for you, I will make a point of writing to you.

I am happy that you are having a pleasant vacation in such a picturesque country, and I hope they will carry on continue as pleasantly as they have begun.

* With sincere affection, Madam,

* My parents and my sister send their best wishes.

[Continuation of retrospective diary entry penned on a train from the Midi to Paris, August 16, 1938:]

Family and friends were kind to us; but the land was still more affectionate…. In the final days [of the vacation], it was dark outside [and] I was sitting in front of our house (l’ou staou99); the sky, resplendent and all ablaze, as mysterious as it was supernatural; I felt the dwindling breeze from a far-away [27] Mistral100 ensnaring me in its web; the streets were of silver, [both] luminous and somber. Everything drew me in…! I left. Dreams are strange things, and my night was one of these.

Last impression, August 14th (Sunday), late in the evening: I was making my way, alone, towards the Porte de la Reine.101 Beautiful young women everywhere! Their youthful appearance stood out against the ramparts of old stone. I heard them laugh, chattering in their relaxed accent, calling out to me,

“Good evening, Jeanne Demeucien!”102 Good evening, lovely ladies! But the [Constance] tower was drawing me to it; my bicycle raced towards its shadow; I circled it: what blackness! Suddenly, there was nothing there but the immense, wild plain, the old canal that the moon barely allowed me to discern, and you, Constance, overpowering in your royal majesty; the diameter of your form twice as large as in the light of day; your height rising, rising higher than the stars above, which, for a moment, are held in your arms. You grow, higher and higher! Oh, Constance! You nearly crushed me like the waves of the old port.

August 15th, at High Mass [at Notre-Dame-des-Sablons in Aigues-Mortes], I played the organ to [28] please the kind parish priest, who brought Communion to my sister during her illness. For that matter, I once had the unspeakable joy of taking Communion at the foot of Yolande’s bed. The priest first refused to serve me, as it was not liturgical, but when I fell to my knees, he broke the host in two and gave it to me.

This morning, August 16th, I left for Paris with Papa and Grandmother, who will stay with me when Papa returns. It’s the first time that I have been separated from my mother: she cried a lot. My sister cried, too. I’ve left and won’t see them again for several months. We have passed La Roche [Larroche-Migennes103]; in [another] two hours we will arrive in Paris. Not too tiring a trip or, at least, not for now. We breakfasted this morning in Avignon.

God bless us!

Thursday 18 August 1938

At noon, I was joyfully reunited with my organ [at St-Esprit]. This evening [played for] Benediction with only one chorister, but all went well. Did not write any music today [29] but sent two letters to dear friends at Aigues-Mortes. First day [back].

Friday 19 August 1938

Nothing particularly noteworthy. The day went by too quickly—it must be better organized. I worked on [the composition of] my étude and my nocturne. On our way to Benediction, we ran into Mlle Defrance, who seemed to be in a frosty mood today; she is back from Lourdes where she witnessed a miracle.

I did the shopping with Grandmother, and I take care of the accounts on a daily basis.

I am falling asleep this evening under the effect of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, which I happened to hear on the TSF.104

Saturday 20 August 1938

Worked on piano in the morning, organ at noon. In the afternoon, I organized all my papers, which occupied me until five. Then, I worked on my étude, my nocturne, and my ballade. At seven, I went to confession at the church; Father de la Motte heard my confession in his office. Afterwards, we talked from the heart. I hide none of my thoughts from him, [30] and he does the same: he is my spiritual advisor. At dinner that evening, Grandmother wished me happy name day [m’a souhaité ma fête].105

Oh! To all be together! And in the same circumstances as before!…

Thursday 25 August 1938

Dined at the home of Noël Gallon. They received me as informally as if I were their daughter. After the meal, we made music for nearly two hours. I played my sacred choral piece, the start of a setting for choir and orchestra of words by Victor Hugo, my étude in F-sharp,106 and my last nocturne, in A major. The last of these held the attention of Noël Gallon, who asked me to play it again and advised me to call it a prelude, because of its form and length. One of the most beautiful days of my life!

At a quarter to six, Benediction. Upon leaving, as I offered my arm to Grandmother, a child of about eight who is in the choir, and whom I’ve often noticed for his gentleness, passed by us with his mother. I leaned towards Grandmother and said to her, “He’s so sweet, that little one!” and because she did not hear me, I repeated the [31] sentence a little more loudly. Thereupon, his mother turned and her face, amid her humble clothes, took on an expression I shall never forget. It was as if an involuntary feeling overcame her shyness and she showed a hint of a timid smile that greatly resembled her son’s. She leaned towards the child and said a few words to him, but he was not brave enough to turn around and I lost sight of them.

Friday 26 August 1938

This evening, after dinner, on the T.S.F., I heard Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony as well as Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 and Léonore overture.

Monday 29 August 1938

This evening, on the T.S.F., I heard Richard Strauss’s Salomé, broadcast from the [Paris] Opera.

Friday 9 September 1938

I haven’t been able to finish my choral piece for tomorrow as I had wanted. This afternoon, copied twelve orchestral pages for this piece. This evening I heard Franck’s Symphony in D minor. Mlle Defrance came over today; she was in [32] a talkative mood. No news for eight days.

Excerpts from Demessieux’s letter to her mother and Yolande in Aigues-Mortes:107

24 September 1938

. . . I again visited the home of Noël Gallon . . . They remain optimistic because they do not wish to believe that certain men are completely insane… Noël Gallon thinks that events could lead to a state of alert, even to general mobilization (that would handle it), but actually to a false alarm…

I showed my teacher [Gallon] a completed fugue on a subject of Bach, and my prelude… He considers my composing to be important work. He found my prelude “perfect,” and the general idea handled very well. I’ll not hide from you (not to boast, but to please you) that he was even moved… That’s how well he understands my music! If only I could play it for you. But that happy time is coming; by then, perhaps other preludes will have appeared…

The new academic year is set to begin on October 3rd. I’ll be able to see Magda Tagliaferro, Marcel Dupré, and Jean Gallon right away…

On the subject of current events [the threat of war], I am ready to make decisions that would be required should the worst happen. Do not worry… I have everything ready for our departure and pray to God that it will not happen.

Draft of letter from Demessieux to Magda Tagliaferro:108

11 October 1938

I’ve learned of your nomination to the status of Officer of the Legion of Honour and am envious today that my letter [and not I] should have the privilege of reaching you to express my joy, and to address to you my sincere very sincere congratulations.

Yesterday I went to the Conservatory certain that I would find you; I was terribly disappointed. Three weeks to be added to two months of separation: it’s so much! But I do not wish to be selfish. Please know that I have put myself back to work very seriously, thinking that you must be satisfied when you hear me again upon [your] return. Again, “see you soon,” though it is always so long to wait. With a warm embrace with much and all my affection,

J.D.

From a letter to Demessieux’s mother and Yolande in Aigues-Mortes:109

15 October 1938

The evening of Papa’s departure [for Aigues-Mortes], I finished off my [composition for] choir110 and the next day rushed to the home of Madame Lantier [Paule Maurice, married to Pierre Lantier]… She told me that I was very gifted in orchestration. I need to touch up my choral composition for presenting it to Henri Busser as soon as possible… I played my other compositions for her. The sacred choral work is first-rate, apparently… She was less thrilled with my étude. As for the nocturne, a total lack of understanding… Not everyone is Noël Gallon . . . She really insisted that I try for [the] Rome [Prize] this year…

From a letter to Demessieux’s parents and Yolande:111

22 October 1938

This evening I went to the Pasdeloup [Orchestra] concert. The program piqued my curiosity because it was all modern works (H. Busser, A. Doyen112…) As I am a future competitor at Fontainebleau113 (sooner or later), I wanted a “lesson.” I received one from Busser.114 His works were classic examples of an entry for Rome, the style of which I am starting to understand…

I felt odd having to go alone to the concert; I would not have gone if the call of music hadn’t been stronger than anything . . .

There are few surviving first-person accounts of Demessieux’s experiences as a student at the Conservatory during the 1938–1939 academic year, the last before war broke out in Europe. Other sources indicate that Demessieux was again a participant in Noël Gallon’s counterpoint and fugue class, and she may have been enrolled once more in Max d’Olonne’s ensemble (chamber music) class.115

As well, on November 30, 1938, Demessieux successfully auditioned to enter the Conservatory organ and improvisation class, becoming at seventeen years of age the youngest current student (others ranged between twenty-one and twenty-seven years). Her classmates that year were returning organ students Ernest Rolland, Jehan Alain, Geneviève Poirier-Denis, Pierre Segond, Denise Raffy, and Marie-Louise Girod, as well as two other newly accepted students, Nelly Montnach, and Jacques Laboureur. In January 1939, Dupré recorded a note beside each student’s name: for Alain he wrote “On leave until Dec. Excellent musician” and for Demessieux, “Very good progress. Very gifted.”116

For the May 10, 1939 examination in organ and improvisation, Demessieux prepared Liszt’s Prelude and Fugue on B-A-C-H. and two works by Bach—the organ chorale Aus tiefer Not, BWV 686 and a Fugue in B minor—and was asked by the jury to perform the Bach fugue.117 All eight students of Dupré’s class also had to improvise a fugue on a given subject and improvise on a thème libre as well.118

As a result of the exam, Demessieux was among the seven students admitted to the May 31, 1939 organ and improvisation competition.119 Four tests of improvisation were imposed—accompany a given plainchant; improvise a chorale (i.e., chorale prelude) on a given theme; improvise a fugue on a subject by Achille Philip; improvise on a thème libre by Joseph Bonnet; performance of one organ piece was also required.

Each candidate, in turn, had seven minutes alone in a separate room to plan how they would execute the tests of improvisation. From these, three tests were selected by the jury; in 1939, they were harmonization of the given plainchant melody, the improvised fugue, and improvisation on a thème libre. In his personal notes concerning the improvisations as performed, Dupré recorded for both Demessieux and Alain: “Good”; “Quite good”; “Good.” For Segond he recorded: “Good +”; “Good”; “Good”. The minutes of the session document the following:

- The President declares that Mssrs Segond and Alain have obtained a First Prize; Mr Segond is first named.

The President declares that Mr Rolland has obtained a Second Prize.

The President declares that Mlle Demessieux has obtained a First Mention.120

From a letter to Yolande:121

17 June 1939

. . . In eight days, it will be the last big day of the 1938–1939 “walk in the park…” [la croisière 1938–1939]. Let’s hope… that I won’t “fall flat” [ne boirai pas le bouillon].122

On June 18, 1939, Demessieux was a contestant in the annual fugue competition for the second time.123 The candidates were placed in individual examination rooms, from 6:30 AM to midnight, with the task of writing a fugue in four parts on a subject by Henri Rabaud. Demessieux was candidate number 16 of 18. At eighteen years of age, she was also the youngest of all. The jury convened on June 19 at 2:00 PM behind closed doors to “hear the work that the candidates had done and to make awards.” The readings of the fugues having ended at 3:40 PM, the jury proceeded to a second reading of each (except nos. 6 and 12), this time as played on piano by jury members Mssrs Bazelaire and Messiaen. The results were announced and recorded in the minutes as follows:

- No. 16 is awarded a First Prize by nine jurors unanimously. No. 16 is declared first.

The original copies may be unsealed to reveal the following names [all First Prizes]: No. 16, Mlle Demessieux; No. 7, Mlle Pangnier; No. 18, Mr Devevey; No. 15, Mlle Falcinelli.

However, the results of the fugue competition printed in Le Monde Musical listed (rightly or wrongly) Mlle Pangnier at the top of the list of First Prize laureates and Mlle Demessieux second.124 Regardless, all four First Prize winners were now eligible to enter a composition class in the autumn of 1939. But first, Demessieux would attend the current year’s competition for the Rome Prize.

From a letter to Yolande:125

2 July 1939

This year’s Rome competition is over; it was yesterday afternoon at the French Institute. First Grand Prize: [Pierre] Maillard-Verger, who composed a very beautiful cantata and who had reached the age limit.126 1st Second Prize: J. J. [Jean-Jacques] Grunenwald, an organ prize and [it] created some discussion among audience members.127 2nd Second Prize: [Raymond] Gallois-Montbrun who, according to general opinion, deserved better.128 [Pierre] Sancan, who presented his work for the first time wrote a very spiritual cantata,129 and it was estimated that he would be among the chosen; he was short two votes. The only two [entrants] in [their] first year received no awards. More and more, I am convinced by Jean Gallon’s thought: there is no need to enter until one is capable of attaining the Grand Prize.

[The cantata by] Gallois was performed extremely well yesterday by artists from the Opéra comique and by Jacqueline P[angnier] and me at the piano. I was surrounded by some of Lévy’s students who had never seen me play from so close…

The day before at the Conservatory, we had played before members of the Institut de musique.130 Florent Schmitt was particularly kind to me… and made me promise to go to his receptions in Saint-Cloud131 when school starts up again . . .

In summer 1939, Demessieux appears not to have written in her diary. She again vacationed in the Midi with her family and corresponded with at least two of her Paris mentors.

Draft of letter from Demessieux to Father de la Motte:132

[Aigues-Mortes,] July 1939

I thought that you would be happy to once again look upon some of the wonderful sights of Nîmes, of which you’ve kept such fond memories; I hope that these vistas brought you some of the same pleasure as if you were here to contemplate these marvels.

Since my arrival, I have enjoyed a beneficial time of rest. Ah! This is not to say that I haven’t been troubled by the temptation to compose! But I repelled it as much as possible during the first days. My hope is that your holiday will bring you the rest and benefits you desire, and that we will be so happy to see. My parents remember themselves kindly to you and join me send their respects and I pray you’ll accept, Father, these my respectful and devoted sentiments as a mark of my regard.

Draft of a letter from Demessieux to Marcel Dupré:133

[Aigues-Mortes,] July 1939

How long the days have been since your departure!134 I’m remorseful when I become aware [illegible] of my silence, [illegible] unintentionally in such contradiction to my feelings.* I have been in the countryside for eight days. The fugue competition was at first occupying all my thoughts and my time.* When I think of the long silence that followed it [your departure], I am sorry and embarrassed. I hope that you will forgive this what is merely an appearance [as concerns writing to you], which is so inconsistent with my feelings.