15

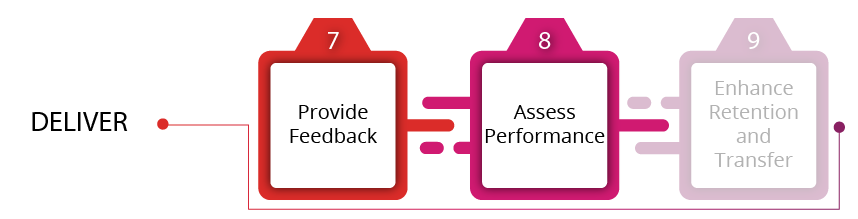

Gagné’s Event 7: Provide Feedback and Event 8: Assess Performance encourage instructors to give learners a variety of ways to demonstrate their understanding and achievement of learning outcomes. Effective assessment in online courses is

- distributed throughout the course,

- linked to learning outcomes, and

- offers learners many chances and methods to demonstrate their learning.

Scaffolded assignments can help you assess a learner’s performance toward an outcome by illustrating their progress.

Credit: University of Waterloo | Image Description (PDF)

Strategies for grading and providing feedback online

Assessment without timely feedback contributes little to learning.

(Chickering & Gamson, 1987, p. 4)

Research has shown that providing effective feedback and feedforward can produce greater learning and helps students gauge whether or not they are meeting the course learning outcomes (Concordia University, 2021). By encouraging learners to reflect on their performance, and to course-correct when necessary, meaningful feedback can enhance critical thinking, reflective practice, and help learners and instructors build trust (Rottman & Rabidoux, 2017).

Effective feedback is

actionable

Provide concrete and specific feedback with actionable items learners can apply when completing their next assignment.

intelligible

Ensure that your feedback is easily understood and be careful not to overwhelm learners—too much feedback can be counterproductive, so concentrate on key elements of performance (Wiggins, 2012).

timely and ongoing

Actionable and intelligible feedback allows learners to implement changes on drafts or future assignments. Timely and ongoing feedback is equally important and helps learners move forward with their learning (Rottman & Rabidoux, 2017). Learners benefit from opportunities to adjust their performance in order to meet criteria for success (Wiggins, 2012). Learners who do not receive feedback at regular intervals may flounder, especially in an online course where opportunities for peer-to-peer and learner-to-instructor engagement may be limited (Center for Academic Innovation, University of Michigan, 2020).

consistent

Connect feedback to learning outcomes and clearly outline criteria for success in assignment instructions and rubrics (Wiggins, 2012; Center for Academic Innovation, University of Michigan, 2020).

Providing feedback is especially important in online courses, because “sometimes the only perceived interaction a learner may have with an instructor is through feedback” (Center for Academic Innovation, University of Michigan, 2020). Providing feedback helps to build connections between instructors and learners, encourages learner engagement, and fosters online learning communities (Centre for Teaching and Learning, Concordia University/Université Concordia, 2021).

You might also consider the feedback you provide as a dialogue with your learners. Offer your perspective on how their work connects to the course goals and have them engage in metacognitive reflection about their learning and how they can take their learning forward to the next task/assessment. This reflection can also be submitted as a follow-up assignment.

An EDII perspective: Feedback formats

Most instructors are used to providing written feedback as it is the most common feedback provided in “hand-in” assessments.

In an online course, instructors can easily provide written (i.e., annotate the document directly or produce summary feedback), verbal, or video feedback. Audio or video feedback may be quicker to record than typing up comments, and allows learners to hear your tone better (Center for Academic Innovation, University of Michigan, 2020).

Feedback through audio or video can be particularly helpful when working with English-language learners, international students, or with assessments where learners are asked to be particularly vulnerable, such as through creative writing, performance, or reflexive practice. By using audio or video for feedback, you can then convey your appreciation of their contribution and the difficult work they put in to complete the assignment. The multiple means of producing feedback may also help you provide feedback to learners with accommodations (e.g., due to disability) in a format that they can more easily access.

Regardless of the medium, pay special attention to how you structure your feedback given that tone can sometimes be difficult to detect (especially in written formats). A common approach is the “sandwich” method: opening with positive feedback, followed by the core constructive pieces, and ending again on a positive note. Feedback can also be offered in one-on-one meetings or peer-feedback elements can be integrated into assignments and activities (Center for Academic Innovation, University of Michigan, 2020).

Examples of how online feedback and grading could work

Quality Advanced

Example 1: Using peer feedback to improve work prior to formal assessment

An advantage of an online course is that there are many ways assignments can be shared among peers, even without third-party tools. A simple approach using only the learning management system (LMS) could be to scaffold an assessment with peer review. Place learners into small group discussion forums where they can submit the first draft of their assignment. Peers in this small group can use a formal rubric to help the original authors improve their work.

Ensure that the goal of these types of exercises are clear. Learners should not be asked to evaluate each other’s work in the same way you would, as they generally feel ill-equipped to do so. Instead, ask them to analyze or react to their peers’ work, i.e.,

to find the thesis statement, the evidence, and the main conclusion, or to identify the ‘strongest sentence,’ a particularly persuasive piece of evidence, and [anything] that the reviewer had to read more than once to understand.

(Nilson & Goodson, 2018, p. 150)

This kind of feedback helps peer authors to recognize the areas in the work that may not have been clearly communicated. The reviewing peer might also be evaluated using a second rubric, which focuses on

- the clarity of their feedback,

- whether the feedback uses course-appropriate language and terms, and

- whether it demonstrates an approach that is intended to help the original author improve their work.

This type of exercise helps build professionalism and communication skills as well as improve the quality of the final product across the class.

Tips:

- If you intend learners to formally evaluate their peers using a rubric and generate a “grade,” then it is recommended that they submit this grade privately to the instructor, while keeping the summary of written feedback public to the small group and/or the individual learner. In this way, you prevent learner–learner tensions or pressures to “give high marks,” and as an instructor you can ensure the “grade” is aligned with the written feedback produced.

- Similar approaches can be used with third-party peer-evaluation tools. These technologies can be more or less intuitive to use, so evaluate functionality closely to ensure it effectively meets your needs. A familiar “low-tech” solution using the LMS is more helpful to learners than a confusing or disorienting third-party application experience.

Here is an example of a rubric to evaluate peer reviewers and their ability to provide constructive written feedback (approximately 250 words) to a narrated PowerPoint presentation summarizing a journal article prepared by a peer.

Credit: Dr. Prameet Sheth, Department of Biomedical and Molecular Sciences, Queen’s University

Quality Essential

Example 2: VALUE rubrics

The VALUE Rubrics are a great resource for creating rubrics that assess intellectual and practical skills. You will want to ensure that your rubrics are well aligned with your learning outcomes and of course the expectations you outline in the assignment instructions.

Activity: Grading criteria

Learning outcomes

This activity is directly aligned with Course Learning Outcome (CLO) 3: Create a varied assessment scheme that scaffolds and supports the learning outcomes of the course and promotes academic integrity and CLO 5: Apply principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and accessibility into your course design to ensure a more equitable learning experience.

Instructions

For this activity, you will create grading criteria for an assessment using a template. A sample rubric has been provided to help you structure your grading criteria. The sample rubric includes grading criteria, weighting, and levels of achievement (excellent, good, developing, marginal, and does not meet criteria/no submission). Note: points values are optional. You may instead wish to assign a holistic grade based on the overall level of achievement.

The nature of this activity does not lend itself to a usable in-line option; as a result, this activity can only be completed via the Word document download.

Download the Grading Criteria Worksheet (DOCX) to complete offline.

Due dates, deadlines, and late policies

Deadlines and weighting

Instructors should clearly identify assignment deadlines, assignment weight, term test dates, and the time frame for returning learner work. Deciding on your individual policies surrounding extended and late work is an important step in your syllabus and course design.

Extensions

There are a number of considerations when developing an extension and late penalty policy. First, institutions and units will have their own guidelines and/or accepted practices for extensions and late policies, so be sure to check with your home department. With institutional policies in mind, set due dates, deadlines, and late penalties with flexibility and fairness in mind.

Flexible deadlines

A learner-centred approach, with built-in flexible deadlines and less punitive late penalties, acknowledges that not all learners learn and work at the same pace.

Instructors and teaching assistants also have to think about their own workload: multiple extension requests can be overwhelming, and flexible deadlines might be difficult for a teaching team (and for learners!) to manage. There is no one policy that will work for every course and it is important to explore various strategies to determine what will work best for your course and teaching team.

Late policies

A clear extension/late penalty policy appropriate to the course, communicated to learners on the syllabus and consistently applied, is strongly recommended.

Strategies for setting due dates, deadlines, and late policies

There are different approaches to flexible deadlines, depending on class size, assignment type, disciplinary norms, and instructor preference. Below are a few strategies faculty have implemented in their courses—this is by no means an exhaustive or prescriptive list.

Examples of how deadlines, due dates, and late policies could work

Quality Essential

Example 3: “Oops Tokens” to communicate care/empathy

“Oops tokens” are a “get out of jail free” card for late assignments; you can offer students one or more per course, as described by Darby & Lang (2019):

Students turn in a token for a no-questions-asked deadline extension, the opportunity to revise and resubmit an assignment or otherwise make up for an unexpected challenge or honest mistake.

Credit: Nilson, 2015, as cited in Darby & Lang, 2019, pp. 98–99.

Quality Essential

Example 4: Grace periods for deadlines

Some instructors provide a permanent grace period for all assessments in the course. For example: “Assignments handed in within 48 hours of the stated deadline will not lose marks. After 48 hours, 10-percent grade deductions will be applied per day.”

Other instructors may frame a similar policy with a more pragmatic reasoning applied. For example: “Late assignments will be accepted without penalty up to the point that I start grading. I have set aside my Thursday afternoons to grade this semester. If you submit after this time, a 10 percent per day–penalty will apply.”

Credit: Jenny Stodola, Professional Development and Educational Scholarship, Faculty of Health Sciences, Queen’s University

Quality Advanced

Example 5: Building in an assessment window and using LMS features to minimize administrative work

Imagine you have a series of short formative quizzes which are completed throughout the course. There are eight quizzes, but in total only account for 10 percent of the grade (low stakes). How could you set yourself up for success and minimize the amount of minding you have to do in relation to this assessment?

- To accommodate the class which may be dispersed across time zones, you set a 24-hour window to complete the quiz.

- You create a bank of questions for which the quiz pulls questions from for each learner, thereby increasing the academic integrity of the assignment.

- The quiz is designed to be automatically graded, or perhaps there is only one question from a set that needs to be manually graded. This reduces the grading workload for you (and the TAs).

- Even if the quiz can be entirely automatically graded, instead of releasing the grades to the learner the moment they finish the quiz, you set the grades to release sometime the following week. This allows you time to sort out any learners who may have legitimate reasons for not being able to complete the quiz during the window (e.g., they may be sick) and still have all grades released at once (i.e., you are not left managing outstanding grades). This also promotes academic integrity as learners who complete the assessment early in the window cannot inform later learners of the correct responses.

Credit: Jenny Stodola, Professional Development and Educational Scholarship, Faculty of Health Sciences, Queen’s University

An EDII perspective on due dates and accommodations

While deadlines are important to help guide learners in their self-directed learning in an online course, regardless of your late policy, you should explicitly note in your syllabus the disability and accessibility accommodations statement (or variation of) that your institution has prepared. Prior to beginning their postsecondary education, it is possible that some learners may not have considered that they may need or qualify for an accommodation in the form of adjusted deadlines. Even for learners who already know they will require an accommodation, this offers an equitable way to provide learners with important information and models responsibility for one’s own learning and self-advocacy.

For example, Equity Services at Queen’s University offers the following statement:

Queen’s University is committed to achieving full accessibility for persons with disabilities. Part of this commitment includes arranging academic accommodations for students with disabilities to ensure they have an equitable opportunity to participate in all of their academic activities. If you are a student with a disability and think you may need accommodations, you are strongly encouraged to contact Student Wellness Services (SWS) and register as early as possible. For more information, including important deadlines, please visit the Student Wellness website at https://www.queensu.ca/studentwellness/accessibility-services.”

Instructors at the University of Toronto are encouraged to add the following accessibility statement to their syllabus:

Students with diverse learning styles and needs are welcome in this course. In particular, if you have a disability or health consideration that may require accommodations, please feel free to approach me and/or the Accessibility Services Office as soon as possible. The Accessibility Services staff are available by appointment to assess specific needs, provide referrals and arrange appropriate accommodations. The sooner you let them and me know your needs, the quicker we can assist you in achieving your learning goals in this course.”

(Centre for Teaching Support & Innovation, University of Toronto, n.d.)

Key take-aways:

- Enhance critical thinking and reflective practice in your course by providing feedback to your learners that is actionable, intelligible, timely and ongoing, and meaningful.

- Take a learner-centred approach to setting due dates and deadlines, embracing flexibility when possible and clearly identifying assignment deadlines, assignment weight, term test dates, and the time frame for returning learner work.