5

Play It As It Lays: A Familiar Tale

By Lindsay Nelson

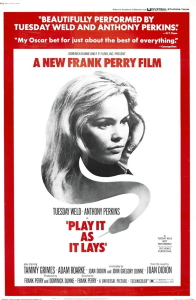

With a portfolio of work spanning all kinds of literary fields from journalism, to fiction, to screenwriting, documentaries and biographies exploring her life, and a fanbase akin to rock and roll groupies, Joan Didion has reached a level of literary stature in America that few living writers can claim. Play It As It Lays, released in 1972, was transmuted from a novel into a screenplay by the author herself and her husband John Gregory Dunne. In her own words: “No, I wasn’t surprised that it would be made into a movie. I wish it was made into a better movie.” “It was just different. It was different. The characters were different. The point was different. Even though I wrote the screenplay.”

The film focuses on the same material that Didion explores in her non-fiction; motherhood, society, depression, and loss serve as a prime case study of women in film considering the main character is an unemployed actress and wife of a director herself, and that the issues that the main character Maria (Tuesday Weld) deals with our specific and relevant to women of eras spanning beyond the mid 20th century. Despite the surface-level feel of its diegetic world, Play It As It Lays is brimming with material to explore the concepts of difference, power, and discrimination in film.

Motherhood, society, depression, loss – these themes are heavily present throughout Didion’s literary corpus, and Play It As It Laysis no different. The film touches on the questions of how women are expected to interact in society at a time when they were thought to be the freest they had ever been. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique had been published and sparked the second wave of feminism seven years before the novel version was published and women had begun to enter the game politically and socially, yet all of the moves in Maria’s life are made by the men in it. Most of the circumstances of Maria’s present tense are orchestrated by her husband, from the predatory film in which Carter exploits her past to her lack of say in her daughter’s life, who Carter has put into an institution for a mental illness that is left vague to the audience. The film centers around the illegal abortion that we never actually hear her say she wants – On the page she enters the house in Encino one year before Roe V. Wade is passed. She does the same on screen the year after the court case. The sounds and visuals of this moment pop up throughout the film as we follow a non-linear journey that shows us the people and places that lead her to her last words of the film: “I know what nothing is, and keep on playing… Why not?”

Along with the obvious presence of women’s issues, Play It As It Lays deals with other characters who are often treated as “other” in film as well as society in general. Kate, Maria’s daughter, who we first hear of through Carter’s chastisement of Maria’s visits to the mental institution that he admitted their daughter into. Though she is brought up by Maria throughout the movie, she is only on-screen briefly during Maria’s visit right before her abortion. The way in which Carter has chosen to deal with his daughter may speak to the stigma of mental illness during the time around and just after the mid-twentieth century. While as viewers we don’t get the full story on Kate’s background, Carter is clearly ashamed of her, made evident by his unwillingness to talk about her with Maria. Another character that stands as an “other” in the film is BZ, Maria’s homosexual film producer friend and the only character that she feels understood by. BZ and Maria share the same nihilism throughout the film, BZ apparently having reached this point of hopelessness before Maria but assuring her that she will “get there”. Play It As It Lays repeats the all too often fate that is held for gay characters in Hollywood from the industry’s birth. As America On Film states about films after the production code allowed for the depiction of gay characters, “The message in these films was clear: Homosexuality was understood as a tragic flaw linked to violence, crime, shame, and more often than not, suicide” (Benshoff, Griffin). Unsurprisingly according to this model, one of the last scenes of the movie shows Maria letting BZ’s head rest on her lap after he takes pills to end his life. Kate and BZ’s characters do not diverge from the typical portrayal of characters who are “others” during this time – they are not depicted as human beings capable of happy, healthy lives. Rather, they are portrayed as characters destined to have lives tinged with hopelessness.

Play It As It Lays is essentially about power and the lack thereof. The diegetic world of the film is a desert in every sense: The setting alternates between the literal Mojave desert where Carter is filming and the moral deserts of Los Angeles and Las Vegas. Maria’s relationships have withered away, the characters of her life are surface-level and flat, and she only feels purpose when she is speeding through the freeways of Los Angeles in her yellow corvette, a destination usually absent. Through the characters that show up it becomes apparent that Maria is in this state that feels to be on the cusp of Limbo and Hell because of the people of her past and present. In her own words, “I’m sick of everybody’s sick arrangements.” The earliest material that she seems to include in this statement is her childhood in Silver Wells, Nevada. Her father was full of empty promises and disappointment yet his influence has an undeniable hold on who she has become. Her husband, though, provides the most glaring examples of power over her life. The first we learn of is his control over their daughter Kate’s treatment. Maria has no say in the life of her own daughter, a tragic and surprising reality for a time of considerable rights for women in relation to history. While Maria is at the facility watching a nurse carry her daughter away after hitting one of the other girls there, a phone call between Maria and Carter discussing the abortion plays, an audio technique that connects the separation that Carter has created between her and her daughter to the even more extreme separation that Carter threatened if Maria does not get the abortion. Carter is pressing her for the details of the abortion that he set up, the scene ends with Maria watching the nurse walk back outside after taking Kate inside and her voice over the phone saying, “They said they’d call me tomorrow and I’d meet them someplace with a pad and a belt and 1,000 dollars in cash, alright Carter?Alright?” Carter had used Kate as a pawn to ensure that Maria would not embarrass him by having another man’s child.

The abortion scene is the most powerful example of the power difference between Maria and Carter. The editing features second-long shots that capture the details that will stick with Maria for the rest of the movie. The quick frames of this scene, as well as the intentionally choppy editing throughout the whole movie, represent the state of mind that Maria is in as a result of her loss of control. The screenwriter was apparently interested in this process: “Didion was fascinated with film editing — “cutting,” she called it. The white spaces, the gaps, in the novel became quick cuts in the film, fragments of Maria’s life repeated out of sequence. In particular, her abortion haunts her: Bloody images, memories of the doctor’s gloved hand — these flit through her mind and across the screen when she and the viewer least expect them.” (Daugherty, 326) The visual and audio details that are captured here work as narration and evidence of the abortion that has just happened. The scene is a vivid one: The whirring of the air conditioner switching on regains the audience’s attention, Maria’s voice asks “What do you do with the baby?” As a bloody, gloved hand throws tissue into the garbage as the metal of the bin clangs, the squeaking of the plastic gloves and the rush of the water from the faucet creates an almost tangible experience of what Maria is going through. Each of these details is shot with extreme close-ups, hyper-focusing on what Maria is left to sort through after she does as her husband asks. On the grander scale, this scene embodies the trauma that women in all of history have been left to clean up after experiences that they did not choose.

The film that Carter shoots of Maria is yet another example of the power moves that keep Maria where he wants her. Right after Maria visits the hypnotherapist in the hope of regressing to her experience as a fetus in order to find out whether they think, the film cuts to a screen that shows Maria pointing at a picture of her dad and his partner Benny Austin. “Didn’t you tell me your father used to ball that waitress in his restaurant in Silver Wells?”, Carter’s voice resounds in the dark screening room. “I don’t want to talk about that”, we hear Maria reply. Carter pushes her to her breaking point: “Do you ever envy Paulette… balling your father?” “Do you ever think about it, on that craps table with the old man, the soft green felt craps table?” “No!” Maria screams and shakes her head on screen as the camera zooms out and reveals the backs of three men sitting and peering up at the film. After discussing Maria’s “shattered personality” Carter defends his vision of the film, “That’s the whole point, it wasn’t a performance,” and defends his probing into her past by saying that she wasn’t his wife yet. Later on in the film, he corrects a journalist who calls Maria his wife: “At that time, my wife” and claims “Existentially, she was giving a performance.” Carter bends the truth according to his needs at the expense of Maria, a snapshot of the norms surrounding power dynamics between men and women.

The dynamics of the business side of the production of the play ironically mirror the issues that the movie itself is concerned with. “Hollywood is largely a boy’s club,” according to Dunne. “[F]or years Joan was tolerated only as an ‘honorary guy’ or perhaps an ‘associate guy,’ whose primary function was to take notes.” “Is John there?” an executive’s assistant would say over the telephone when calling for his master. ‘This is Joan.’ ‘Tell John to call when he gets home.’” (Daugherty, 324) Even in a movie about the suppression of women the author and screenwriter herself is treated as a secondary figure in the whole endeavor. This speaks volumes of the truth that Play It As It Lays has to offer, along with its faults. It is also worth mentioning that the cast was not particularly diverse, the majority of the characters on screen are white. Keeping in mind that this film is one about the industry it exists in, this would be an accurate representation of the society in which Maria operates. Even as late as the 1970’s Hollywood was an industry slow to represent society as a whole.

The most notable dissenting voices of Play It As It Lays come from film critics Pauline Kael and Stanley Kaufmann, who had a similar opinion in regard to Didion herself. In his scathing review of Play It As It LaysKaufmann writes, “The film is just as pretentious, posturing, empty, and, finally, commercially clever as the book.” He held back no more with the team involved: “Didion and her husband John Gregory Dunne wrote the screenplay and, it’s said, selected Frank Perry to direct. Perfect. A phony serious novelist is naturally drawn to a phony serious director.” Another important voice in film criticism, Kael wrote in The New Yorker that Didion created the ‘“ultimate princess fantasy,” which is, “to be so glamorous sensitive and beautiful that you have to be taken care of; you are simply too sensitive for this world– you see the truth, and so you suffer more than ordinary people, and can’t function.” (Daugherty, 325) These reviews disregard Didion’s bold embrace of taboo topics such as abortion and mothers of children with disabilities which made Play It As It Laysstand out from its contemporaries. I would agree thatPlay It As It Laysis a repeat of the cliche, overused trope of the disillusioned Hollywood starlet, but I don’t believe that deems it unnecessary or unuseful. The repetitiveness seems to be a tactful vehicle toward the film’s message. The fact that Maria is so obviously recognizable speaks to the accuracy of her character, she must be truly present in society since movies continue to be made about her.

Spanning beyond the years of Play It As It Lays, Joan Didion has continued to contribute to conversations about phenomena for whatever reason kept hush-hush in society. The film adaptation of Play It As It Laysundoubtedly comes with its own issues that remain present in Hollywood today, but it was and is a timely commentary on the lingering reality for women, beyond what’s reflected on paper.

REFERENCES

Benshoff, Harry M. and Griffin, Sean. America on Film. Representing Race, Class, Gender and Sexuality at the Movies. 3rd Edition. Wiley, 2020.

Daugherty, Tracy. Last Love Song: a Biography of Joan Didion. Griffin, 2016.

Kauffmann, Stanley. “Stanley Kauffmann on Films.” New Republic, vol. 167, no. 22, Dec. 1972, 22–35. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=10240680&site=ehost-live.