6

Fantastic Planet: Coexistence in Spite of Difference

By Tia Daversa

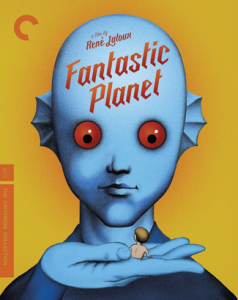

I’ll never forget the first time I saw the cover for Fantastic Planet. It was in 2016, around when The Criterion Collection remastered and republished it; the cover was mustard yellow, striking and bright around the edges, and in the center was an otherworldly blue figure with piercing fish-like red eyes. In its palm it held a small human, they were staring at each other. I was immediately intrigued, I asked my husband about it and all he said was, “you would really like that movie”; months later we rented it from the Corvallis library and finally got around to watching it, needless to say, I was obsessed. I was entranced by the stunning visuals produced by the rudimentary animation style, and paired with the eerie avant-garde lounge-y jazz score it was completely hypnotic. Creatures unlike anything I had imagined and humans on the scale of ants played out a story that felt completely unique but familiar.

The narrative of Fantastic Planet details the struggle between the ruling species of the planet Ygam, known as the Draags, and humans, known as Oms, who have come to inhabit the planet after a catastrophic Earth event. The Draags are massive compared to the Oms, seemingly hundreds of times larger; they dominate the humans not only in size, but in intellectual and spiritual capabilities. Some Oms are “domesticated”, dressed up and kept in doll houses as pets; while other Oms are “wild” and live in small colonies away from Draag society. Within the story of the film, one human helps lead the others in a quest for freedom from the Draag’s oppression and for a planet to call their own, while unwittingly creating peace between them. This resolution is found when the Oms repurpose unused Draag technology to fly themselves to the planet’s moon (in the film this moon is called “the wild planet”, translated, this is the original French title La Planete sauvage). Although the moon was utilized for Draag spiritual meditation, the Draags and Oms are able to compromise; with their fantastical technology, the Draags create a synthetic planet that orbits Ygam for the humans to inhabit, leaving the Oms with a planet of their own and the Draags in reverence of the human’s intelligence and evolutionary capabilities. In this way, Fantastic Planet serves as an allegory for discrimination and the power dynamics that arise out of fundamental difference, while also presenting a utopian vision of how such dynamics can come together to create a culture of peace and coexistence.

Fantastic Planet, released in 1973, carries many imprints left by the circumstances of its creation. Both the director, Rene Laloux, and the co-writer/animator, Roland Topor, started their artistic careers in the avant-garde art movements of the 1960s. Rene Laloux spent time as a counselor at a remarkably progressive psychiatric hospital, where he collaborated with the patients to create short films that found moderate success in France (Brooke). Roland Topor was the child of two Jewish refugees from Warsaw; already an established cartoonist, he had co-founded the surrealist art movement known as the Panic movement (Brooke). After meeting at a French film festival, the two men hit it off and began producing animated short films, including Les Escargots (1966) and Les Temps Morts (1965). When they began work on Fantastic Planet, Laloux and Topor made the decision to animate and produce the film in Prague, Czechoslovakia; the animation was well-received and well-funded in Prague and they signed a contract with the renowned Jiri Trnka animation studio. Production was halted several times due to unrest that accompanied the “Prague Spring” political uprising, the biggest disruption came in August of 1968 when Soviet forces invaded Czechoslovakia. The invasion caused seventy-two deaths and production on Fantastic Planet did not resume until the next year (Spysz). The looming Soviet presence and the anxiety caused by the invasion, as well as Topor’s first-hand experience facing Nazi Germany, very well could have contributed to the film’s themes on oppression and power. The Draags universal society could be a mirror of what the Soviet Union represented at the time, and the organization of Draag society contrasted against the scattered Om communities creates a sense of fundamental difference between the two species.

To further this sense of difference between the Draags and the Oms, the film employed a variety of techniques. The most striking of these techniques is the sheer scale difference between the two species. The Draags tower above the humans, in scenes of conflict the Draags are able to simply step on the Oms or flick them away. The cinematography of the film supports this contrast, scenes where the Oms are in control are filmed from the ground up, effectively placing the viewer in their perspective. Alternatively, scenes where the Draags are exerting power or influence are framed up high from their sightline. In addition, the Draag’s fish-like appearance and blue skin give the two main conflicting species a plethora of visually obvious physical differences. Difference is also found in the alien race’s spiritual and intellectual capabilities. The Draag society is far-advanced; the film presents many of their technologies as wondrous and nearly magic, and makes a point of the immense education that Draag children receive. These differences serve as the basis for the power struggle at the heart of the film.

Fantastic Planet is a unique story about power in that the Draags are exerting control over the Oms in the way that humans exert control over animals. Whether it’s capturing and taming wild Oms, forcing two tame Oms to fight to the death, or exterminating wild groups with poison gas, the film seems to draw many ties between the Oms and animals. This is why some people interpret the film as an animal rights piece, but personally, I feel that the film’s story and the meaning that the directors encoded into it are more aligned with the plight for human equality. This film utilizes animal comparisons to create discomfort within the audience, leaving the viewer with the unsettling realization of how easily your autonomy and rights can be stripped away. Overall, the narrative and story arc push for equity and equal rights in the face of difference, especially the right for humans to stand up against oppressive, tyrannical governments.

To elaborate further on these themes, I’d like to take a closer look at the Draag society and its treatment of the Oms. The Draags and their universal governance system have made the control and containment of Oms a state matter, similar to how the Soviet Union executed an invasion of Czechoslovakia to preserve state interests. In one scene that depicts this hegemonic power struggle, Draag council members debate the possibility of Oms possessing higher intelligence and evolutionary capabilities. One character, Master Sinh, remarks on the Oms’ possible intelligence that is evidenced by traces of organized life on Earth. The other council members are quick to dismiss the possibility and immediately move to discussing “de-Oming” measures, drastic bouts of genocide carried out in places where wild Oms are known to gather and inhabitat. These eerie scenes of mass gassing and culling of the Oms are even more sinister when Topor’s experience with the concentration camps of World War II is taken into consideration. The practice of de-Oming and the humiliating life of “domesticated” Oms are just a few of the ways in which the Draags utilize fundamental differences to exert power over the humans. I would view these acts as not only an abuse of power but also an example of active discrimination.

Discrimination is represented in the film in a couple of different ways. But first, I’d like to touch on the ever-present whiteness shown in the Om population. While one of the writers (Topor) was Jewish, it seems that the possibility of people of color in space was lost during the production of the film. While I don’t think that this oversight severely hampers the ending message of fundamental togetherness, I do view this as a real shame as it also serves to bolster the notorious “white male savior” trope found commonly in science fiction texts. In their paper Science Fiction (Whiteness), Green et al. discuss the history of this lack of diversity within science fiction, stating that “one major trope within the science fiction genre is the relative absence of blackness… even post–civil rights science fiction remains largely the realm of whiteness” (Green et al.). They also discuss differing skin tones being used to denote “otherness” or villainy. While this use of skin tones is evident in Fantastic Planet, I feel that the lack of racial diversity among the Oms is a product of the rudimentary animation style (the film was animated with paper cutouts layered on top of each other) and lack of forethought regarding the design of the Oms in the film, as opposed to a purposeful and pernicious lack of people of color. In any case, discrimination in other forms plays a huge role in the narrative of the film.

At the heart of the conflict in Fantastic Planet lies the struggle for freedom from discrimination. On the planet Ygam, humans face extreme oppression because of their differences from the ruling class. This reflects the systems of oppression that are present in our world, both at the time of production and the present. In an article detailing social identities and their relationship with systems of oppression, the Smithsonian Institute explains that “society’s institutions, such as government, education, and culture, all contribute or reinforce the oppression of marginalized social groups while elevating dominant social groups” (Social Identities). This is exactly the kind of dynamic evident in the film’s narrative. There is a cultural Draag belief that Oms are unintelligent and undeserving of respect so as a result the ruling system of power (Draag council) reinforces this belief while also perpetuating oppression and violence against Oms. The plight of the Oms and their eventual flight to freedom can serve as an example for what it looks like when humans band together and find strength in community, it also reflects the invasion during the Prague Spring and the civilian-based defenses that arose out of necessity. Another interesting note on the topic of discrimination is the dichotomy between the domesticated Oms, dressed up and kept as housepets by the Draags, and wild Oms, living in abandoned Draag structures or braving the wilds. When Terr, the main protagonist, flees his Draag captor and joins a group of wild Oms, he is shunned and made fun of for his costume and his understanding of Draag writing and culture. The leader of the wild Oms calls it a “grave offense” to learn Draag knowledge and forces Terr to battle a wild Om as punishment. As Terr’s Draag knowledge serves to ultimately free the Oms, this could be seen as an allegory to the importance of pooling knowledge, especially in small, grassroots activist movements.

Even though Fantastic Planet has remained devoid of widespread mainstream success, the core of the narrative continues to enlighten new viewers to the perils of perpetuating oppression based on physical/intellectual difference. Regardless of the lack of box office success, the film has sustained a cult following and critical acclaim. Through its psychedelic visuals and haunting score, the film has stood the test of time and remained singularly unique in its vision. Additionally, the cinematography and editing work together to force the audience to view oppression from the perspective of humans under unimaginable circumstances and enlighten them to the injustice that many humans still face in the present day. These factors all culminate in Fantastic Planet being a strong statement against state-perpetrated violence and discrimination in all forms.

REFERENCES

Brooke, Michael. “Fantastic Planet: Gambous Amalga.” The Criterion Collection, 21 June 2016, www.criterion.com/current/posts/4112-fantastic-planet-gambous-amalga.

Green, Michael, et al. “Science Fiction (Whiteness).” Race in American Film: Voices and Visions That Shaped a Nation, edited by Daniel Bernardi and Michael Green, vol. 3, Greenwood, 2017, pp. 773-781. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX7357300284/GVRL?u=lbcc&sid=GVRL&xid=bf379f79. Accessed 28 Feb. 2021.

“Social Identities and Systems of Oppression.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institute, 17 July 2020, nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/social-identities-and-systems-oppression.

Spysz, Anna. “Springtime for Prague.” Local Life, 2007, www.local-life.com/prague/articles/prague-spring.