4 Chapter 4: Critical Approaches to Digital Literacy

Maha Bali and Cheryl Brown

Overview

Using the Internet is probably a daily activity for many of you, but sometimes it’s such second nature we don’t stop to think about what underlies the information we use. In this chapter, we help you think about issues of equity in the online context and explore who predominantly contributes to the information we read. We look at who is and who isn’t represented in the digital space and how everyday platforms we use are themselves skewed towards particular viewpoints and preconceptions. We provide you with some strategies and tools to be critical in understanding the platforms you use and the information you read. We also foreground some of the negative and positive aspects of social media in constraining and enabling different people’s voices.

Chapter Topics:

- Introduction

- Thinking About Context

- Learning to Be Critical

- Voices: Who Is Represented in Digital Space and Who Isn’t?

- Critical Digital Literacies: Digital Platforms

- Questioning Digital Platforms

- Positioning Yourself Online

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Develop a critical awareness of online contexts.

- Appraise online content.

- Develop critical questioning skills.

- Understand how some individuals or groups may be marginalized online.

- Recognize issues of access to information sources.

- Understand bias of digital platforms.

- Reflect on positionality and information privilege.

- Develop increased self-awareness of biases.

Introduction

One of the most important elements of being online is the ability to be critically aware of where content comes from and who has authored it. You should be able to ask questions that will enable you to better understand context. In chapter 2, you explored the history of literacy and who traditionally has had access to the ability to read and write. Although digital technology and, specifically, the Internet have to some extent increased access to information, it is still inequitable.

There is an old saying: “Knowledge is power” (it’s so old that no one really knows who said it first). In many cultures knowledge used to be very closely guarded by elders or experts. It may have been locked away for safekeeping in libraries (such as the Library of Alexandria), where only privileged people like rulers and scribes could access it.

Technology has contributed to changes in who owns and can access information. So much so that some people believe the Internet can be credited with facilitating the coming together of our global community (in that it allows people to access information and engage with the world unhindered by distance). However, it has also contributed to the fragmentation of society as it is a place for conflict and disagreement as well as new forms of exclusion.

Thinking About Context

In the following sections, you will learn some strategies and habits to help you take a critical look at whatever you find online. However, we don’t usually verify every single piece of information we find online, so keep in mind that contextual knowledge can be the driver that motivates you to dig deeper.

Activity 4.1: Demonstrate Context

Imagine someone asks you to watch a video of US president Donald Trump standing by a wall in the White House, near the image above, telling ABC’s David Muir the following: “But when you look at this tremendous sea of love—I call it a sea of love—it’s really something special that all these people travelled here from all parts of the country, maybe the world, but all parts of the country. Hard for them to get here.”

- If your teacher showed you this video, would you believe it?

- If you received this video on social media (e.g., Facebook, WhatsApp) would you think it was real?

- What would make you doubt the authenticity of the scene?

- How would you verify its authenticity, or its lack of authenticity?

- Before reading the text below, try to verify the authenticity of the video above and keep track of the steps you took to do so.

The trick about that video is that you need to have a lot of contextual awareness to be suspicious of its authenticity: You need to recognize that the picture Trump is pointing at is of the Muslim Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, and that it is a picture of Muslims in pilgrimage. You need to connect that with a knowledge that Trump has repeatedly used negative rhetoric against Islam and Muslims, and that calling this a “Sea of Love” sounds out of sync with his usual rhetoric. Someone who does not have this contextual knowledge may not seek to verify the authenticity of the video; and someone who has this contextual knowledge, but is not habitually skeptical, or does not know how to verify audiovisual material, may simply believe it and move on.

Once you’ve finished trying to verify the authenticity of the video above, see this blog post for the full video.

One of the pitfalls in critical thinking is that sometimes we find ourselves compelled to confirm our own biases. Confirmation bias is the tendency to selectively search for and interpret information in a way that confirms your own pre-existing beliefs and ideas. In other words, you interpret new information such that it becomes compatible with your existing beliefs, and if it can’t be interpreted thus, you either choose to ignore it or call it an exception (Aryasomayajula, 2017).

Information and knowledge have significant roles in supporting and maintaining the power structures of the modern world. We should be aware that just because information may be available and accessible, doesn’t mean it is equitable and without bias. In principle it is possible that as long as people have the resources to access the Internet, they are in a position to make their voices heard. However, in reality, a vast majority of Internet users are not really able to make themselves heard and their concerns receive little attention. Perhaps it’s more accurate to suggest that the Internet offers ordinary people the potential for power. Regardless, it is more likely used for specific purposes by those who already have power, whether symbolic, political, or social.

Activity 4.2: Equity and Bias

Watch this video by Binna Kandola on Diffusion Bias, and try a couple of these Implicit Association Tests to explore some of your own hidden biases. There may be several reasons why some online content contains misinformation:

- Ignorance; sometimes people just get things wrong or make mistakes with no malice or ulterior motive (unintentional).

- The desire to present a one-sided view based on personal beliefs (religious, political, cultural).

- The desire to promote a message that supports commercial gain (advertising, commercial bias).

- Deliberately spreading propaganda by a ruling body or organization (usually political).

- Limited perspectives (missing “voices”):

- Who is represented in digital space and who isn’t?

- Who is able to participate?

- Who has access to what already exists?

- Even when multiple perspectives are side by side, which voices are considered authoritative? Who sets the standard for what is considered credible?

Learning to Be Critical

Trying to figure out whether a source has expertise, authority, and trustworthiness is not always easy. Mike Caulfield, in his book Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers (2017), offers a useful outline for the fact-checking process. If you’re in doubt about something you’ve found online:

- Look around to see if someone else has already fact-checked the claim or provided a synthesis of research.

- Go “upstream” to the original source: Most Web content is not original. Get to the original source to understand the trustworthiness of the information.

- Read laterally: Once you get to the source of a claim, read what other people have said about the source (publication, author, etc.). The truth is in the network.

- Circle back: If you get lost, or hit dead ends, or find yourself going down an increasingly confusing rabbit hole, back up and start over knowing what you know now. You’re likely to take a more informed path with different search terms and better decisions about what paths to follow.

Activity 4.3: How to Be Critical

What is the purpose of a website? Is it to provide information? To sell you something? To share ideas? Explore the following three websites about different aspects of digital literacy to find out who owns or produces the content:

- “Developing Digital Literacy Skills“

- “Critical Digital Literacy: Ten Key Readings for Our Distrustful Media Age”

- “Digital Literacy“

Keep in mind:

- There is often a page called About or About Us which should give you some clues about the intent of the authors and the content.

- There is often a link to a Terms and Conditions page that highlights legal aspects of content ownership and how you can use that content.

- There may be a Testimonials or Reviews page that tells you what other people think of the services or content.

- There may be a Help or Support page to enable you to get the best out of the site.

- If there is a Cart at the top of the page or a page called Prices, the site may be trying to sell you something.

- Contact pages often tell you where the producer is based by providing an address or map.

Check the authority of the author or producer:

- See if you can find out who the author is. Is it an individual or an organization?

- Is the author a recognized expert in the field? Are they affiliated or connected to any organization? If so, is the organization credible?

- Is the organization or body producing the information reputable?

- Does the author provide sources for their information? Can you go and check out these original sources?

- Can you contact the author or organization for clarification of any content?

Look at the content:

- How old is the information or content? Is the information current? Is the source (website) updated regularly? Does it need to be?

- Can you tell why the content has been published? Are the goals of the publisher clearly stated?

- Is the content factual or does it contain opinions? Is the content biased in any way?

- Does the content provide links or information to other sites? Are these authoritative? Do they present alternative views or information?

- Can you check the accuracy of the content against other sources?

- Does the site try to get you to register or sign up to receiving other content by email?

- Does the website contain advertising? (This could affect the content.)

Questions adapted from McGill (2017) and Caulfield (2017), CC-BY-SA.

Activity 4.4: Spot the Fake

Use the points in the bulleted lists in Activity 4.3: How to be Critical to see if you can complete the following activities.

- One of the websites below is fake, see if you can spot it:

- Website A: Fangtooth

- Website B: Warty Frogfish

- Website C: Tree Octopus

- How long did it take you to spot the fake? How did you know the website was fake? Did you do any checks on other sites to verify the information contained in the sites? Does the fake website have links to true information? [See the end of this activity for the answer]:

- Can birds intentionally start fires? Try to verify the claim.

- Is the article “Australian Birds Have Weaponized Fire” coming from a reputable source? Can the National Post be trusted?

- Return to the National Post article and locate the link to the original scientific study. Is this a reputable journal? What can you determine about it? How about the authors of the study – do they have relevant expertise?

- Note what the paper says and covers and compare it to what the reporting source covers. Are the facts of the news story correct? Are there elements of the work the news story leaves out? Do your findings surprise you?

Answer: C) The Tree Octopus is fake

Activity adapted from Caulfield (2018), CC-BY

Asking Critical Questions

Asking questions is always a good idea. It will make you a better learner and thinker. Critical questioning means going deeper into your questioning and not just asking Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How, but instead asking more descriptive questions like “Who benefits from this?” “What is getting in the way of action?” “Why has it been this way for so long?” or “How can we change this for our good?”

For more descriptive questions, see the Global Digital Citizen Foundation’s “Ultimate Cheatsheet for Critical Thinking.”

Critical thinking isn’t only about being skeptical. In the words of the Global Digital Citizen Foundation, critical thinking is “clear, rational, logical, and independent thinking.” It’s about “practising mindful communication and problem-solving with freedom from bias or egocentric tendency.” There are also feminist approaches to thinking critically that involve empathy and contextuality, and trying to adopt the viewpoint and frame of reference of the “other” while refraining from judging them (Thayer-Bacon; Belenkey et al.).

Activity 4.5: Ask Critical Questions

Here are two news articles about Digital Literacy

- “Digital Literacy Is ‘Hot’ but Not Important“

- “Digital Literacy ‘as Important as Reading and Writing“

Use some of the critical-questioning prompts from the Global Citizen Cheatsheet to practice critical inquiry. Ask questions of these articles and try to take your inquiry and thinking to a critical level.

Voices: Who Is Represented in Digital Space and Who Isn’t?

The Internet has provided a vehicle for people to transcend geography and political borders by interacting with information and communities from across the world. The notion of global citizenship has taken on a new meaning in educational contexts as a world view, or a set of values, that prepares students for a global or world society. It is an acknowledgement that your nation or place of residence is only part of the world and that you are part of a global society.

As a student and a global citizen it is important that you are aware of yourself and your place in the world, and of others’ places in the world, in order to begin to become aware of other people’s perspectives. A tool like Gapminder—a non-profit resource for global data and statistics—can be useful in helping you do this. Gapminder allows students and teachers to look at the world from social, economic, and environmental perspectives. Gapminder works on the premise that by having a data-based view of the world you can “fight the most devastating myths by building a fact-based world view that everyone understands.” It’s described by the Geographical Association of the UK as an “invaluable resource for making sense of contested concepts like uneven development, inequality and change.” This is particularly valuable given how commercial social media services and search engines have contributed to the spread of misinformation.

As useful as Gapminder can be as an online resource, with so much data and so many visualizations, we must also always question the sources of data, how the data sets were chosen, and the biases in the methodological approaches used in this statistical modelling style, etc. That is, no data or information is neutral and “merely a fact”; rather, data and information are “chosen facts” that can suggest a certain picture of a situation. Gapminder is one useful tool. But it should not be the only tool you use.

Activity 4.6: Evaluate Graphical Representations of the World

The intention of this activity is to give you a sense and opinion of how the world has been visually depicted and how this representation is actually an altered form of reality. Think about where you are geographically located. To what extent are, or have, common visualizations of the world (e.g., maps) shaped your beliefs about where you are from in relation to other countries?

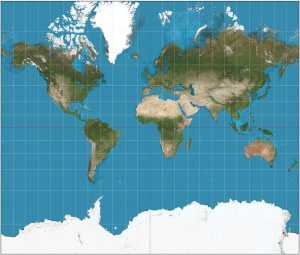

Below are two versions of the world map, the Mercator Projection and the Gall-Peter Projection.

- What differences in perspective are shown by these two projections?

- Choose one of these online resources to help you think about the differences:

- See what you can find out about other maps, such as the Dymaxion and Peirce Quincuncial maps:

- Can you find any earlier maps of the world (e.g., from the ancient, pre-modern, or medieval periods)? How did “we” represent “ourselves” in the past? Who is responsible for this representation of “us”?

The aim of this activity is to help you evaluate the different ways in which representations of particular places and positions in the global system occur. What implications do these different ways of representing ourselves and others have for our own biases?

The Mercator map is the most popular map; it is used by Google, Wikipedia, the UN, and in many other popular depictions of the world. However, the Mercator map distorts perception of the size of continents, departing from their actual land-mass size, and rendering North America and Greenland as larger than Africa, for example. What does this do to our ability to frame and understand importance, dominance, and geopolitical relationships, specifically in light of the historical power configurations among developing countries (mostly minimized, marginalized, in the Mercator projection)?

Critical Digital Literacies: Digital Platforms

So far in this chapter we have mainly focused on developing a critical approach to the actual information we find online. The following section introduces a new focus: on maintaining a critical perspective on the digital platforms we use every day, such as Google, Facebook, and others. It is important to recognize how digital platforms can be used in digital citizenship and activism. At the same time, it is also important to recognize that not all people around the world have equal access to these platforms, and that some people risk more than others by using these platforms.

On Bias in Google and Wikipedia

Two spaces many of us use as a first step when searching for information are Google and Wikipedia

- Go to Google Images, and look up the term “professor.” What do you notice about the search results? Do many of the results have anything in common?

- Now search for images of “Egypt” and compare what you find with what happens when you look up images of “Cairo.” What do you notice about the difference between the search results?

You may find that most results for “Egypt” show historical monuments from the time of the Pharaohs such as the pyramids and the Sphinx while many results for “Cairo” show the modern-day city with modern buildings and bridges. The former reinforces stereotypes about Egypt as a place where people live in the desert and ride camels, missing the modern-day Egypt in favour of showing famous historical images.

Bias in Search Algorithms

As you’ll read more about in Chapter 5, search algorithms are not “neutral.” Google’s algorithm specifically depends on proxies of popularity, which means that the top search results Google returns to us are biased. They are biased in the sense that content produced by marginal people or representing marginal views may be less visible, but also that “where content shows up in search engine results is also tied to the amount of money and optimization that is in play around that content.” Even more alarming, Zeynep Tufecki has reported that the money-making recommender algorithm of YouTube (which is owned by Google) increasingly shows users more inflammatory content because it keeps them on the site longer and therefore exposes them to more ads.

Bias in Wikipedia Content and Editing

Wikipedia is often celebrated as a democratic digital space, an encyclopedia of crowd-sourced information that can be edited by anyone in the world. The credibility of information on Wikipedia is now considered less of a problem than when the site first began, as editors frequently check up on pages and highlight areas that require additional citation, occasionally removing information not supported by credible sources. Research has shown that these frequently edited articles on Wikipedia are likely to be on par with articles on Encyclopedia Britannica in terms of accuracy and neutrality.

- Bias in Wikipedia content standards: While anyone can contribute articles and make changes to Wikipedia, they must meet the standards that have been set by the organization. While some of these standards serve to remove bias, for example by ensuring that people don’t create biographical entries for themselves or their friends, others, such as the requirement that all content be sourced from previously published material, means that pages about marginalized people for whom there isn’t much existing information on the web, make the cut less often. The requirement that all facts be cited by a “credible” and “verifiable” source also impacts the content that is available in different languages. If you are writing an article for Wikipedia in your native language and can’t find a credible reference to link to, you may have to resort to a reference for it in a different language. However, this assumes such references exist or are accessible to you.

- Differences in Wikipedia content based on language and region: One notable example is the comparison between the English and Arabic Wikipedia pages for the Arab–Israeli War in October 1973. While both articles relay mostly the same facts, the Arabic version states that Egypt won that war, while the English version lists the result as a victory for the Israeli military. The Wikipedia articles don’t balance these perspectives in both languages: each version of Wikipedia tells a different version of history. Both articles cite their sources, which shows that history is told from the writer’s perspective. There is more than one version of history, but what matters here is to clarify how the wisdom of the crowd does not ensure the different versions coexist in any one Wikipedia article.

Research studies such as Reagle and Rhue’s look at gender bias on Wikipedia versus on Britannica (2011), highlight how Wikipedia reproduces gender, racial, and other biases. There has been a lot of coverage of gender bias in Wikipedia specifically (see “Wikipedia’s Hostility To Women,” in The Atlantic, October 21, 2015). Wikipedia has its own article on gender bias on Wikipedia, which starts by showing that as of 2011, 90% of Wikipedia’s volunteer editors were male.

Gender imbalance on Wikipedia is usually discussed in terms of the number of Wikipedia articles on female figures versus the number on male figures, as well as the length of articles on female figures or topics of female interest versus the length of those on male figures and topics. It is also important to note that within controversial topics (e.g., GamerGate) that involve gender sensitivity, the number and strength of male editors often results in a male view being the one disseminated on Wikipedia, rather than one balanced by the inclusion of females’ views. Beyond the numbers, there has been evidence of harassment of some female editors, gender imbalance, and hostility towards women, and even though Wikipedia has had several projects to try to counter the gender imbalance and increase women’s contributions in Wikipedia, several have not fared well.

Activity 4.8: Comparing Wikipedia Pages

If you are bilingual or multilingual, open two Wikipedia pages, in two different languages, on the same historical, political, or potentially controversial topic:

- Check out the Wikipedia page for the topic in each language.

- Are the pages direct translations or do they tell different stories?

If you are not bilingual or multilingual, try using Google Translate to see if different Wikipedia translations on the same topic are identical or different (sometimes just looking at the length is an indication). Google Translate is not 100% accurate, but it is relatively good for translations between English, French, German, and Spanish (Of course, those are the dominant Western languages, but they are also the ones that are easier to translate from English versus, say, Chinese or Arabic).

Questioning Digital Platforms

While many of us enjoy free-to-use platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and many other services, we should also be aware that these are commercial providers, with profit-making intentions, which may not (and often do not) have their users’ best interests in mind and may make ethically questionable choices.

Activity 4.9: Critiquing Digital Platforms

Watch this video by Chris Gilliard on platform capitalism.

In late 2017, Chris Gilliard posted a tweet asking:

What’s the most absurd/invasive thing that tech platforms do or have done that sounds made-up but is actually true?

— Should old surveillance be forgot (@hypervisible) December 29, 2017

Try answering that question yourself before reading the responses.

If you go return to Chris’s tweet, you will find several links to reports of outrageous and ethically problematic things tech platforms have done. Examples include:

- When Facebook used their algorithm to selectively manage people’s timelines and manipulate their emotions and moods.

- When an unsubscribe service sold user emails to Uber.

Can you remember an instance of a digital platform doing something invasive or unethical? Why did it matter to you? In what ways did the platform infringe upon the rights of groups or individuals? What is the worst thing that has happened directly to you or to someone you know? What, in your view, is the most dangerous thing tech platforms can do?

Activity 4.10: Investigate Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policies

Have you ever read the Terms and Conditions or Privacy Policies of platforms you use? Some of them have extremely long and virtually unreadable policies, but others are much more straightforward.

Choose two of the platforms you use often and compare their Terms of Service or Privacy Policies.

- What did you learn?

- By using the platform are you taking risks that you had not previously been aware of?

- Can you determine, for example, if you retain the copyright for material you post to one of these platforms? (Squires, D.)

Activity 4.11: Surveillance and Online Safety

Read this article on how Facebook’s mistranslation of a Palestinian’s update resulted in him being arrested.

- Why do you think this happened?

- What kind of questions does it raise about who holds power in digital platforms?

- What does this incident tell us about how digital platforms work, and about what they prioritize?

- What kinds of issues does it raise about surveillance and privacy online?

- What kind of biases does it reveal?

- How does it connect to issues of race and racial profiling online and offline? Would a similar Facebook update by a person of greater privilege have created the same kind of reaction?

Activity 4.12: Reflecting on Digital Activism

Read the following article: “How Young Activists Deploy Digital Tools for Social Change.”

Note how Nabela Noor, a young American Muslim, started out as a YouTube personality doing non-activist videos related to makeup. However, Islamophobic discourses surrounding the election of Trump spurred her into using YouTube to respond. In this way, social media empowered Noor to have a voice in a space where young Muslim voices were largely unheard in the dominant discourse. But it is also important to note that she would not have been able to do this without her previous digital literacy and following on YouTube, and definitely not without access to YouTube (which is banned altogether in some countries) and a good Internet connection (a privilege some people in rural US and Canadian towns don’t have; the same applies to many in the global South).

Note how the other activist in the article, the young Esra’a Al-Shafei from Bahrain, talks about her pathway to online activism advocating for the rights of marginalized people in the Arab region. Note how she does not show her face on camera, for her own safety.

Many other forms of digital activism have been seen in recent years, such as the roles of Twitter and Facebook in the Arab Spring (however, the real revolution took place in the streets). But using social media for activism can be dangerous, and risky. Some political bloggers get arrested or worse.

Twitter has had a central role in campaigns such as #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo. This brief video, “How #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo Went From Hashtags to Movements” featuring Tarana Burke (the founder of #MeToo) and Patrisse Cullors (the founder of #BlackLivesMatter) shows how the movements started and grew, and also what both founders consider to be a new model of activism.

While these campaigns allow people to gather and work together and find supporters, they also make them more vulnerable to personal and systemic harassment, which can occasionally move outside the screen and spill into their everyday lives. Moreover, social media has been used to amplify extremist ideologies such as white supremacy, sometimes affording anonymity to people who spread hatred and violence that can lead to physical harm. This PBS podcast suggests approaches to fight back against these online aggressions.

Think of some examples of social media use for activism, and ask yourself:

- Who has the privilege and luxury to be a digital activist?

- In what ways does digital activism reproduce patterns of offline activism, especially in terms of whose voices get heard?

- How does digital activism counter patterns of offline privilege and activism, allowing new forms of activism and previously marginalized voices to be heard?

Positioning Yourself Online

Positionality is the notion that your culture, ethnicity, gender, and many other aspects of your life (for example, education, religion, heritage, age, ability, language, etc.) influence your beliefs and values.

We felt that since this chapter reminds us to recognize the influence of the author and context on texts we encounter online, we should make our own positionality explicit: We are both scholars from the global South.

Maha is Egyptian and is an associate professor of practice at the Center for Learning and Teaching at the American University in Cairo (AUC) in Egypt. Since 2003, her work has involved supporting faculty in their teaching, including integration of technology. She also teaches undergraduate students, and recently designed and taught a course on digital literacies. Maha has a strong interest in equity and social justice issues, and her PhD from the University of Sheffield focused on the development of critical thinking for students at AUC. She identifies very much with her postcolonial hybridity, because even though she was born in Kuwait as an Egyptian to Egyptian parents, and grew up in Kuwait, she went through British and American education, lived briefly in the US and UK as an adult, and works at an American institution. All of this makes her more aware of postcolonial issues and global inequalities and inequity. Being a woman, a mom (to a girl), and a feminist also makes her very aware of gender issues. This is why you will find many examples across the text that mention postcolonial, language (especially Arabic), and gender issues with the digital world.

Cheryl is South African and an associate professor of e-learning in the School of Education Studies and Leadership at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand. Cheryl has lived and worked in South Africa, Australia, and, recently, New Zealand. A common interest of hers has centred around access to ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies) and how they facilitate or inhibit students’ participation in learning. In the past few years she has explored more closely the role technological devices (for example, cell phones and laptops) play in students’ learning in a developing context and in the development of students’ digital literacy practices. In her PhD, she explored how inequity influences students’ digital experience and therefore their digital identities. As a mother to two boys who have grown up with access to technology she feels it’s important to develop a healthy and critical awareness of both digital opportunities and challenges.

Activity 4.13: Reflect on Your Positionality

Think about who you are and about your past experiences in the world, the things you’re passionate about, and the things that trigger pain or anger.

- How might these things shape your view of the world, the ways in which you approach new information, and the ways you choose to use digital platforms?

- What might your biases be?

- What might your fears be?

- How might they influence your digital literacy?

Activity 4.14: Self-Test

What have you learned through undertaking the activities in this chapter? Has the process of working through critical approaches to digital literacy changed:

- the way you access information online?

- your social media presence?

- the way you search online?

- how you evaluate information online?

- the websites you regularly use?

- your understanding of who contributes to information on the Internet?

- how you personally interact and engage with people online?

- what information you will contribute online?

Make a list of the changes you plan to make in how you will use the Internet in the future.

Is there any personal action you can take to increase representation and equality on the Internet?

References

The objective analysis and evaluation of an issue in order to form a judgement.

The tendency to selectively search for and interpret information in a way that confirms one’s own pre-existing beliefs and ideas.

Information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote a political cause or a particular point of view.

The notion that personal values, views, identity, and location in time and space influence how one understands the world.