Thai Phan-Quang, photographer.

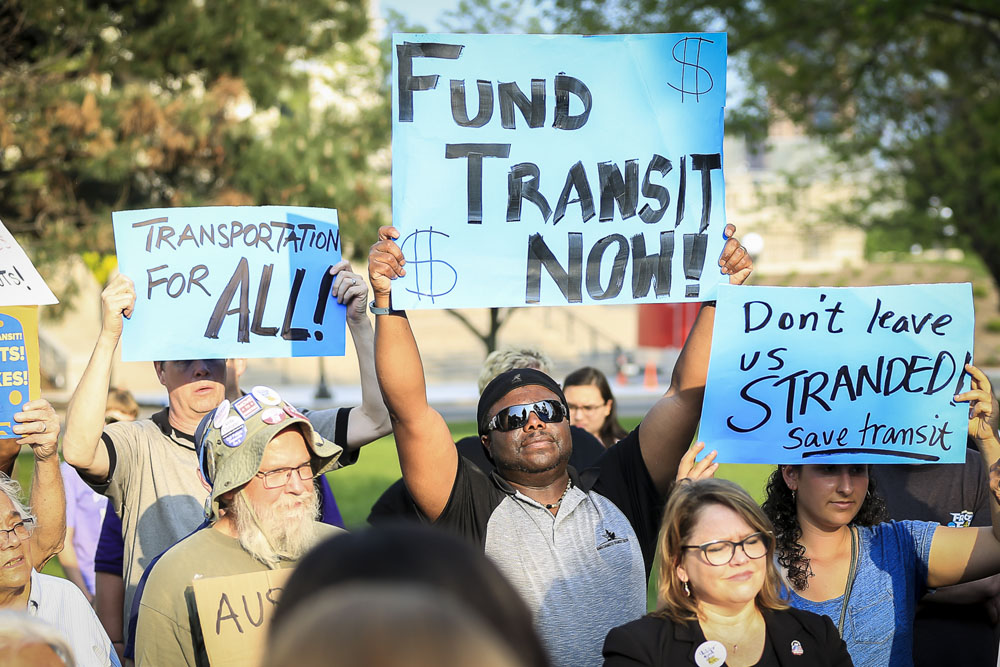

An equitable transportation system is one that provides affordable transportation, creates quality jobs, promotes safe and inclusive communities, and focuses on results that benefit all. It also strengthens the economy by ensuring that all people—regardless of race, income, or ability—can connect to the education and work opportunities they need to participate in and contribute to society and the economy. (PolicyLink, 2016, p. 2)

Transportation is so important that, after housing, it is the second highest expenditure for U.S. families. In the previous section we learned that health equity is central to living the life you want to live and to building and maintaining our social networks. Equally important is the ability to move through space. As much as the internet has made it possible to do just about anything without leaving the couch, we still have to haul our bodies from place to place to live full and healthy lives. How do you go to work, the health clinic, the grocery store, to see your family, and back home again? How far apart are these resources from one another? Are they well connected by transit or do you need to drive? Once you park your car or get off your bus are there safe ways to get to your destination as a pedestrian? How much do you pay for public transportation or auto-related expenses? Transportation is so important that, after housing, it is the second highest expenditure for U.S. families.

My first internship after college was at a non-profit environmental organization about 20 miles from where I lived with my parents. The office was located at the suburban Amherst Campus of the State University of New York (SUNY) Buffalo, a campus built in the 1960s when lots of institutions were leaving the city along the routes created by new government funded highway systems. The internship wasn’t paid, but the experience led directly to my first real full-time job. Using public transportation, the commute would have taken at least two hours each way. With my parents’ car and two different highways, however, I was able to get there in about 30 minutes and park for free.

Transportation equity is directly tied to land-use planning decisions. Locating the new SUNY Buffalo Campus in the suburbs rather than the city led to a cascade of transportation and development impacts. Millions of dollars in transportation infrastructure connected the campus to the region. Student and faculty housing was created on and around the suburban campus instead of in the city. Money was spent on new buses to get students from the city campus to the suburban campus—money that could have been spent elsewhere. For those not living on campus, walking and biking to school became next to impossible.

Transportation connects people to opportunities and resources. Transportation connects people to opportunities and resources. Your transportation options depend on how much money you have and where you live, and as we learned in the history section, these have a lot to do with the color of your skin. The same policies and decisions that built U.S. cities and metropolitan regions around cars also set up the conditions for today’s transportation disparities. When we read about the history of American cities and suburbs we learned that white families were able to use FHA loans to buy affordable homes in newly developed suburbs, while Black and Native American families were denied the use of these loans. Black families were forced to remain in the city where rents were higher than suburban mortgages. Native American families were not able to use FHA loans to build homes on reservations, and were thus unable to build wealth through homeownership.[1] This left most Black and Native American families in the city or on the reservations with few financial resources. White families in the suburbs were able to build wealth through homeownership and had enough resources for at least one car.[2]As the tax base shifted from cities to suburbs, available urban resources declined. Even if kids in urban areas could walk to school, their walk might not be as safe and that school would have a lower budget than a suburban school that was accessible by foot.

Along with the FHA loans, the Federal Highway Act of 1956 was central to the shift from city to suburbs. This policy transformed billions of taxpayer dollars (combined with state allocations and user fees) into high-speed connections between new suburban housing developments and urban job centers. Starting in the 1960s and continuing today, companies also moved their headquarters from the city to the suburbs (where most of their executives lived), shifting thousands of jobs with them.

…transportation inequality is not just about accessing transit. It’s also about who does or who does not benefit from transportation projects… Who benefitted from highway spending? Suburban real estate developers and financiers, construction companies, and suburban homeowners. Who lost? People living in the neighborhoods like Rondo in St. Paul, Minnesota, where 600 homes were demolished to make way for Interstate Highway 94. Those who remain live with the noise and air pollution, and cannot walk through their neighborhood without going out of their way to find a pedestrian crossing. Just like health inequality is not just about access to healthcare, transportation inequality is not just about access to transit. It’s also about who does or who does not benefit from transportation projects (in terms of economic, social, educational, and health outcomes, for example), who does or does not bear the burden of increased public transportation costs, and who does or does not have a say in transportation decisions.

Let’s start by looking at who does and who does not have good access to transportation options. People who cannot afford a car (or gas), who are too young or old to drive, or whose physical disabilities prevent them from driving all depend on public transportation to meet their daily needs. Changes in routes or schedules impact transit-dependent people more than those who have access to a car. If your commute goes from half an hour to two hours because of a change in bus routes, you have less time with your family, higher child care costs, and less time to go to school or work. If you are late to work because the bus schedule is inconsistent, you may lose your job. If you are only able to apply for positions on or near a transit route you may miss out on better opportunities in suburban office parks, or be unable to work nights or weekends when bus service is typically limited.

The poorest families in the U.S. spend nearly 40% of their budget on transportation… Who bears the burden of transportation costs? Since everyone pays the same amount to use public transportation, buy a gallon of gas, and pay tolls, income level dictates the percentage transportation takes of one’s overall budget. The poorest families in the U.S. spend nearly 40% of their budget on transportation, while middle-income families spend about 19%[3] That leaves middle-income families with an extra 21% of their budget to spend on other things like education, healthcare, and entertainment. Current government transportation budgeting, however, favors wealthier riders and drivers. Spending on car-centered infrastructure, suburban buses, and commuter rail well outweighs spending on city buses.

Motorists have been the primary beneficiaries of federal and state transportation investment. A total of 80% of federal transportation dollars goes toward highways, while all other modes of travel compete for the remaining 20% (Rubin, 2009, p. 22).

It’s ironic that low-income people, who spend the largest portion of their incomes on transportation, disproportionately subsidize wealthier public transit riders. Transportation equity researcher Robert Bullard puts it this way: a “‘reverse Robin Hood’ policy operates in many transit systems where the meager resources of poor, transit-dependent riders are used to subsidize affluent transit riders” (Bullard, 2003, p. 1197). These subsidies are often justified as ways to reduce the number of suburban car commuters.

…transportation equity is closely tied to health and environmental equity. Transportation equity is about the fair distribution of the positive and negative impacts of transportation projects and policies. Transportation construction projects are typically big and costly, involving lots of land and money. Think about the amount of space and capital needed to construct or repair a highway. Even smaller-scale projects that make it easier for cars to move through cities frequently make it harder and more dangerous for pedestrians, cyclists, and transit users to get around. From this perspective, transportation equity is closely tied to health and environmental equity. Expenditures that favor car transport over public transportation result in higher emissions and poorer air quality. Low-income neighborhoods are more likely to be located near major roadways, and these residents suffer disproportionately from air pollution burdens such as increased asthma. Unsafe pedestrian crossings and a lack of safe bike routes can lead to collisions with vehicles. Low-income people are twice as likely to be killed while walking than higher-income people. African Americans and Latinos are two times as likely to be killed while walking than Whites.[4] Those who rely on public transportation may not have easy access to grocery stores and may have to shop at convenience stores with fewer healthy food options.

Transportation equity is also about who is able to participate in decisions about service and infrastructure. What recourse do you have if your bus line is slated for reduced service? What if there are no benches or safe crossings near your stop? Who do you call if the air quality is so bad that your elderly neighbors have trouble being outside in the summer? What if a new highway is slated to run through the middle of your neighborhood? What if a new rail line is proposed through your neighborhood but won’t be stopping there? How do you know that your input was taken into account? How can you find out who else cares about these issues? Do you have any legal recourse? A study of Metropolitan Planning Organizations, the groups with the most say in how billions of transportation dollars are spent in many U.S. regions, showed a disproportionately high number of white suburban committee representatives. Furthermore, representatives are appointed, rather than directly elected by the people their decisions impact.

The siting of the SUNY Buffalo Amherst Campus, the location of my first internship, was highly controversial. A broad and diverse coalition of members of campus and community groups and both local newspapers argued for a site near Buffalo’s downtown, which was already feeling the economic impacts of suburbanization. A city location would have been much easier for people without cars to access, and closer to low-income neighborhoods. Nevertheless, the suburban location won out and campus construction began in 1968. The impacts of this decision—the shift of millions of dollars of resources and increased spending on new vehicle access routes, including expanded expressways to and from campus—are still felt today.

What neighborhoods are getting these amenities? Who benefits? Many public universities in the U.S. that developed suburban campuses in the late 1960s and early 1970s have recently relocated portions of their campuses back downtown. SUNY Buffalo, for example, recently built a new medical school complex downtown. In response to lessons learned from uniformly car-centric decades, urban designers, city planners, and real estate developers have focused new energy and ideas on making walkable, bikeable, transit-rich urban neighborhoods. In cities like Minneapolis and St. Paul, though, we still spend much more on car infrastructure, and plans for city bike systems that connect to buses and light rail are high priorities for city officials. Who these efforts are for, however, remains an important question. Which neighborhoods are getting these amenities? Who benefits?

Two moments in the history of the Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul, Minnesota, illustrate the importance of understanding how major transportation projects impact low-income neighborhoods: the construction of Highway I-94 and the construction of the Green Line Light Rail Transit (LRT). The I-94 story has no silver lining, and its effects continue to burden Rondo residents while benefiting car users. The LRT story, in contrast, illustrates the power of coordinated community action to shift public policy towards equity.

St. Paul’s mainly African American Rondo neighborhood had a thriving economy and strong cultural community in the decades before and after World War II. But in the late 1950s, as part of the Federal Highway Program, plans were made for a connection between the two downtowns of Minneapolis and St. Paul and out to the eastern and western suburbs. Rather than an alignment within an existing railroad right of way to the north along the industrial corridor of Pierce Butler Drive, transportation planners chose one cutting through the middle of Rondo, a choice which ultimately destroyed hundreds of homes and small businesses.

Rev. George Davis tried his best to stay in his home. When he refused to move, authorities forcibly removed him. Police arrived at the preacher’s house bearing axes and sledgehammers, a sight that caused his 13-year-old grandson to cry. “They were knocking holes in the walls, breaking the windows, tearing up the plumbing…,” recalled Nathaniel Khaliq, now 66, who is Davis’ grandson. “I was crying because it looked like something bad happened” (Yuen, 2010).

The impacts of the I-94 location went beyond physical destruction. As the federal highway program and FHA loans pulled white Minnesotans away from the city, residents who remained in Rondo suffered the impacts of a diminished tax base, abandoned properties, and disinvestments in schools and other public programs. They were also left with the ongoing health impacts of air pollution from car emissions.

Today, former and current Rondo residents commemorate their neighborhood through Rondo Days, an annual parade and festival that draws thousands of participants, many of whom grew up in homes that were demolished for the freeway. A new commemorative plaza (https://www.aia-mn.org/rondo-commemorative-plaza/) on Concordia Avenue, a frontage road for I-94, interprets Rondo’s history and the history of how the federally funded highway system cut through many other Black neighborhoods across the U.S.

Forty years later, Rondo was at the center of another transportation equity controversy with national implications. Planning began in earnest in 2001 to connect the downtowns of Minneapolis and St. Paul with light rail transit along an eleven-mile stretch of University Avenue. The Green Line was the biggest piece of public infrastructure added to the neighborhoods since the construction of I-94.

No transit stops were planned in the most transit-dependent neighborhoods along University Avenue, including the bulk of Old Rondo. Stops for Us, a campaign led by a deeply diverse coalition including Rondo residents and leaders, won a victory for transportation equity that benefited thousands of residents and businesses and shifted federal transportation policy towards a more socially just model. As a result of their work, three additional stops were constructed: at Hamline, Victoria, and Western Avenues. Rondo residents, some whose parents and grandparents fought I-94, joined forces with residents of nearby Frogtown and transportation equity advocates to win the stops, and to win support for small business owners who faced traffic disruptions and loss of parking during and after construction.

Stops for Us allies rightly framed the uneven negative impacts of the implementation of the Green Line as an equity issue. Gaining the stops was a hard-won victory requiring multiple tactics: lobbying public officials, researching station locations and demographics, leveraging the National Environmental Policy Act process, drafting state legislation, monitoring public meetings, testifying at public hearings, and implementing a media strategy. The movement benefited from the involvement of community leaders experienced in civil rights and social justice, and from the broad range of culturally specific organizations along the corridor. In 2010, the coalition won the Environmental Protection Agencies Environmental Justice Award,

….for its efforts to form a broad-based partnership to secure the construction of three new light rail transit stations, which will provide access for the transit dependent communities of East University Avenue, connecting residents to housing, jobs, education and the many amenities located throughout the Twin Cities metropolitan region. (US EPA, 2010)

I-94, however, remains a barrier and health hazard for Rondo residents. They still hope to find ways to remedy the destruction, and are advocating today for options including new pedestrian bridges and/or a highway “lid” that would cover I-94 with new green space. Examples of highway lids can be found as close as Duluth and as far away as Seattle. Rondo residents are also concerned that the Green Line is leading to increases in rent and tax assessments for long-time residents who may need to move out of the neighborhood.

As you will read in the next chapter, information equity, like health and transportation equity, is key to ensuring fair and just access to opportunities and resources for everyone.

Works Cited

Bullard, R. D. (2003). Just sustainabilities. Retrieved from https://books-google-com.ezp1.lib.umn.edu/books/about/Just_Sustainabilities.html?id=I7QBbofQGu4C

PolicyLink. (2016). Transportation for all: Good for families, communities, and the economy. Retrieved from http://www.policylink.org/sites/default/files/Transportation-for-All-FINAL-05-10-16.pdf

Rubin, V. (2009). All aboard! Making equity and inclusion central to federal transportation policy. Retrieved September 6, 2016, from http://www.policylink.org/find-resources/library/all-aboard-making-equity-and-inclusion-central-to-federal-transportation-policy

US EPA, O. (2010). Environmental Justice Awards 2010 [Announcements Schedules]. Retrieved August 11, 2015, from http://www.epa.gov/compliance/environmentaljustice/index.html

Wellman, G. C. (2014). Transportation apartheid: The role of transportation policy in societal inequality. Public Works Management & Policy, 19(4), 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X14545808

Yuen, L. (2010). Central Corridor: In the shadow of Rondo. Retrieved November 11, 2018, from https://www.thecurrent.org/feature/2010/04/20/centcorridor3-rondo

Endnotes

- See "All-in-Nation: An America that works for all" at https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/AllInNation.pdf ↵

- My family benefited from the GI Bill. After my dad served in the Korean War he received a free education that allowed him to shift from his job in the steel mill to teaching. The jobs paid about the same, but when the steel mills in Buffalo, NY, laid off 60,000 people in the 1970s and 1980s, the shift in jobs made possible through the GI Bill meant our family remained financially stable. Other families never recovered. At that time many Black veterans did not have the same opportunities to use GI Bill funds. See Katznelson, I. (2005). When affirmative action was white: An untold history of racial inequality in twentieth-century America. New York: W.W. Norton & Company - Portions of the book are available at https://tinyurl.com/y83gekl9 ↵

- See Wellman, G. C. (2014). Transportation apartheid: The role of transportation policy in societal inequality. Public Works Management & Policy, 19(4), 334–339. At http://login.ezproxy.lib.umn.edu/login?url=https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X14545808

↵

↵ - See Zimmerman, S., Lieberman, M., Kramer, K., & Sadler, B. (2015). At the intersection of active transportation and equity. At https://www.apha.org/~/media/files/pdf/topics/environment/srts_activetranspequity_report_2015.ashx ↵