Ali Boese

The word design, like the words art, research, and writing, seems so broad that it’s hard to define. The word design, like the words art, research, and writing, seems so broad that it’s hard to define. And just like anyone can paint a picture, conduct a survey, or write a story, anyone can design. You and your roommate may have come up with a way to arrange your furniture so that you had more privacy or a better study space. You may have created a poster to advertise a performance or club meeting, choosing just the right font and images to capture the spirit of the event. In either case you had a goal in mind, tried out several different solutions, and weighed each solution against a set of criteria before making a final decision. This is design. And while the designs that non-professional designers create could be linked back to larger equity issues (who has the final say, you or your roommate? Who decides what a private space or a study space should feel like? What is the performance about? Where is it held? Who is able to go? Whose interpretation of the “spirit of the event” is right?), our concern here is with the relationships between equity and the work of design professionals. Their decisions have the potential to impact the most people. And some design professionals, like landscape architects and interior designers, are licensed and legally required to serve the public good.

In the next two chapters, we will look at two related types of professional design practices: design thinking and discipline-specific design. Design thinking is the more generic practice, with specific processes that can be used by professionals or by anyone looking for a creative way to solve a problem or come up with a new idea. Fields of discipline-specific design include graphic design, interior design, landscape architecture, architecture, apparel design, experience design, systems design, and product design. Each discipline-specific design field has its own design processes (though they are similar) and draws on its own areas of expertise.

In this chapter we will look at the professional practice of design thinking—how it works and how it’s used.In this chapter we will look at the professional practice of design thinking—how it works and how it’s used. Over the past 20 years new academic programs, centers, and entire companies have emerged that offer design thinking training and services to corporations, organizations, and government agencies. IDEO, an international design firm with over 700 employees, is the largest, with a portfolio of work that is deep and diverse. Los Angeles County, home to the country’s largest voting district, worked with IDEO to rethink its entire voting system. Help Glide, a software startup, worked with IDEO to develop a watch band that captures photos and videos for the Apple Watch. Design thinking services are also offered by non-profit design centers like the Minnesota Design Center at the University of Minnesota (MDC). The MDC, the Minnesota Department of Human Services, and the Future Services Institute used a strategic design thinking process to approach the many systemic barriers facing adults who live in corporate foster care facilities.

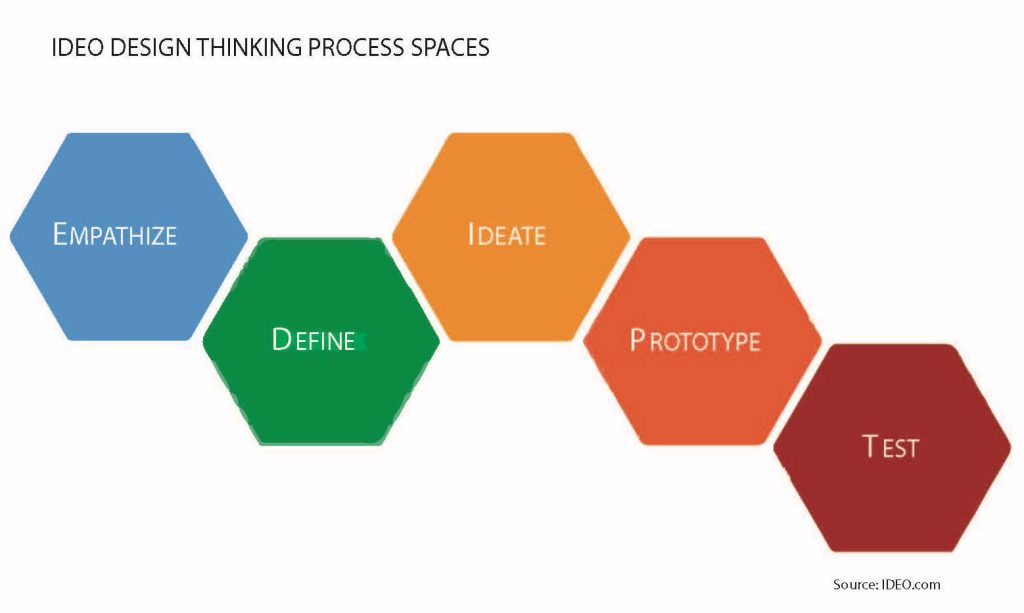

So how does design thinking work? Professionals use many different processes—some with three steps, some with five or more, some with three big steps that are then divided into smaller steps. Most use different words to describe roughly the same activities, making it difficult to compare, and, for our purposes, difficult to map the ways each design thinking process relates to equity. That said, some design thinking processes are more established than others because they are taught to students at places like Stanford’s Design School or MIT’s Design Lab. Students from these programs have gone on to teach or to create big influential design firms and to promote similar design thinking processes. Later in this chapter we will dig into the design thinking process model developed by IDEO leaders Tim Brown and Jocelyn Wyatt and described in the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Some clues to how design thinking works can be found in its history. Some clues to how design thinking works can be found in its history. As you will read in the article “Design thinking origin story plus some of the people who made it all happen,” by Jo Szczepanska, design thinking as a strategy for problem solving emerged in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Early design thinking approaches drew on methods of established and emerging professions as diverse as engineering, architecture, industrial design, psychology, and computer science. Initially developed as a way to tackle complex environmental and social issues, design thinking today has become a sort of “umbrella term” that refers to any multi-disciplinary, human-centered project involving research and rapid idea generation.[1] “Human-centered” means that the design team aims to find a solution that fits the needs of the end user, not just the company or organization that hired the designer to come up with a solution. The word “research” is used a bit loosely in design thinking to mean gathering information needed to generate and test out solutions and ideas and then critically evaluating that information in light of the project at hand (though some design thinking projects may include social science, ergonometric, or market studies that do generate new knowledge and contribute to larger bodies of research). “Rapid idea generation” (sometimes called “rapid ideation”) refers to the step in which a design team quickly generates lots of ideas, tests them, modifies them, and re-tests them until the team and its clients believe they have created a workable solution.

What happens after the design thinking is over? That depends on how much time, money, and willpower is needed and is in place to make something happen. A non-profit might use the results of a design thinking process to solicit support from funders. A for-profit company might bring the ideas to its research and development team. A city agency might put the ideas out for public input and to generate support.

When you compare the main design thinking process models and distill their basic components you will find that they can all be organized into some version of the same cycle of activities. When you compare the main design thinking process models and distill their basic components you will find that they can all be organized into some version of the same cycle of activities. In “Design Thinking for Social Innovation,” Tim Brown and Jocelyn Wyatt outline what many see as the foundational process for design thinking. Brown is President and CEO of IDEO and Wyatt leads its Social Innovation group. Their process has been critiqued and adapted by others to better fit social and racial equity goals, so we will spend some time here talking through their ideas. For Brown and Wyatt (and in all of the design thinking models), design thinking is not a linear path. Instead, it is iterative, looping among three big activities that they label as inspiration, ideation, and implementation:

Think of inspiration as the problem or opportunity that motivates the search for solutions; ideation as the process of generating, developing and testing ideas; and implementation as the path that leads from the project stage into people’s lives. (Brown and Wyatt, 2010, p. 33)

For Brown and Wyatt, inspiration is more than just being moved to create something—more than feeling inspired, though that helps. Inspiration in this design thinking process sets out the “Why?” behind the whole endeavor. What is the issue or problem that the team is trying to address? What do they need to know about that issue or problem? What constraints do they need to be aware of? Goals and constraints provide a focus and framework for the design thinking process called “the design brief” (sometimes called a “problem statement”).

In any design thinking process, the design brief is key. In any design thinking process, the design brief is key. The team measures the success of every idea they generate against the brief. The brief must be focused enough for the team to dig in without asking themselves “What are we doing again?” all the time, but not so narrow that the outcome seems predetermined. For example, if a design team starts off with a brief that says “improve kids’ health,” they won’t know where to begin. But if a design team starts off with a design brief that asks, “How can we encourage kids to be more physically active?” they can start finding information about what works to get kids active now or what is it about kids’ brains and attitudes that leads them to adopt or reject new behaviors. They can pull together research articles, talk to kids, teachers, and parents, and observe kids at recreation centers. The brief may also say that the solution must be cheap to develop and use, giving the team additional criteria to shape and evaluate their ideas. Every design brief is based on a set of implicit assumptions about what is good and right and what kinds of information and research are valid.

With a design brief and lots of background information to draw upon, the team moves on to ideation. Ideation is a fancy word for coming up with ideas or brainstorming. The goal here is to synthesize what the team has learned in the inspiration phase into new insights about the problem or issue. Team members may develop a set of “design principles” based on what they have learned so far—such as, our solution needs to facilitate both group and individual play, or our solution should work for students who do not have a computer at home. These principles can be used to develop multiple solutions. Ideation involves divergent thinking—generating many different solutions based on the same information. You can think of it as a kind of informed brainstorming. The team then takes all of their ideas and gradually sorts out the ones that best fit their project brief.

What if, during the ideation phase, the team finds new information that challenges the goals set out in the brief?What if, during the ideation phase, the team finds new information that challenges the goals set out in the brief? If that happens, the team can move back to inspiration, reframe their brief and then move on to ideation. This “moving backwards and then moving forward,” also called a feedback loop, is central to the design process. When you hear someone say that design is “iterative,” they are referring to the fact that designers generate and test multiple solutions and in the process discover new information that may change the brief. They adjust the brief and create another set of stronger ideas and move on from there.

How do you move from something as immaterial as an idea or concept to a physical object, implementable system, or inhabitable place? Once the group has identified the idea or ideas that best fit the brief, they move from ideation to implementation. In the implementation phase the team converts big ideas into “things” that can be tested and eventually manufactured, installed, or built. This is often a challenging step. How do you move from something as immaterial as an idea or concept to a physical object, implementable system, or inhabitable place? To make this leap, the team begins by creating rough prototypes or mock-ups. A prototype isn’t fully operational, and it needs to be cheap and fast. As you will see in the video, paper prototypes may be flimsy and goofy looking, but the process of making them and talking about them leads to valuable insights and more refined prototypes, which in turn give the team a stepping stone to help them move from a big idea to a more refined product. There is something about taking an idea and making something physical and tangible that sparks new ideas and also opens up new conversations in the group. Prototypes are good conversation starters with clients or users, and can also help a project team identify potential problems before rolling out their ideas.

“Prototyping in Design Thinking: How to Avoid Six Common Pitfalls,” by Rikke Dam and Teo Siang, offers practical tips for prototyping which include: work quickly, use cheap materials, don’t “fall in love” with what you make, and know that failed prototypes can yield important insights.[2] This video, by the Academy for Innovation and Entrepreneurship at the University of Maryland, depicts the process of prototyping. The team decides to use two prototyping methods—a physical prototype and a role-play prototype to test out a system to improve the experience of biking on campus. The physical prototype gives them a way of illustrating and talking through the “Bike Buddy” system, while the role-play prototype allows them to practice sharing the idea with real people. In this (now classic) video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M66ZU2PCIcM), a team works through a design process to create a better shopping cart, ending with a prototype that can be tested out in a grocery store.[3]

Depending on how well the prototyping goes, a team may move forward to refining and further developing their idea or may find that they need to go back to an earlier phase. In the shopping cart example, the team will likely refine the idea further but keep the basic concepts. In the “Bike Buddy” example, the team would likely take the feedback from talking with people and consider issues of safety more carefully. Perhaps they would decide that the “buddies” need to go through safety training and that biking in busy areas like Washington, DC, is too big a jump for new riders with or without a buddy. When the team has created what they feel is a workable design based on what they learned in the prototyping phase, they’re ready to move forward with creating the final product or service. At this point they would likely hand off their idea to a discipline-specific designer, like a systems designer or landscape architect in the case of the bike-buddy idea, or a manufacturing expert in the case of the shopping cart. They might also create a communication strategy. Who needs to know about this new process or solution? What is the best way to reach them?

Ali Boese

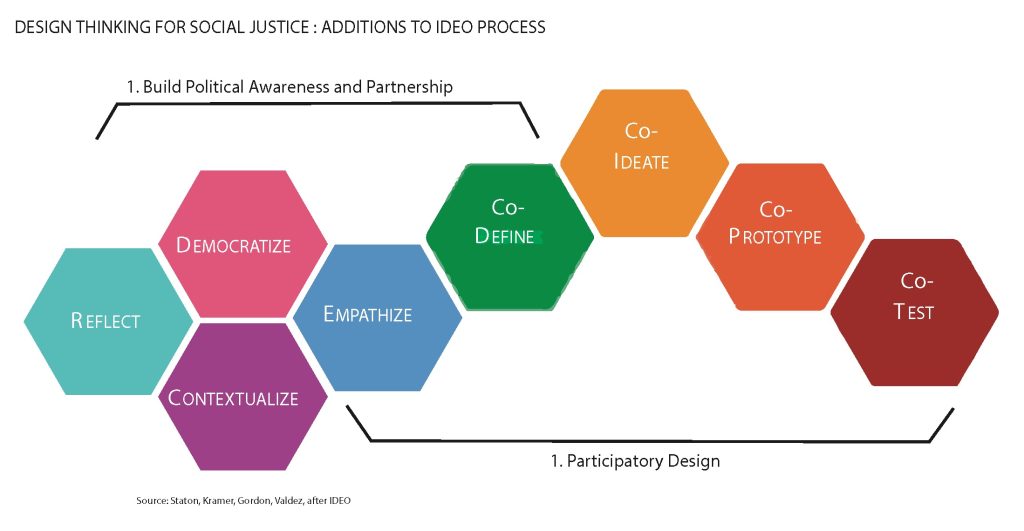

Can design thinking – its process and outcomes – help make our communities and systems more just and fair?This very brief overview of design thinking emphasized how the process unfolds from brief to implementation, but does design thinking relate to issues of equity? Can design thinking—its process and outcomes—help make our communities and systems more just and fair? In the next article you will read, “From the Technical to the Political: Democratizing Design Thinking,” by Staton, Kramer, Gordon, and Valdez, the authors discuss exactly that. Their goal is to critique current design thinking processes and to explore the potential of design thinking as a tool for equity and social justice. They argue that existing models of design thinking often offer only technical fixes for problems that are rooted in unjust economic systems. For instance, a design thinking process aimed at helping people access healthy foods might suggest a new neighborhood grocery store without asking whether or not people can afford fresh vegetables in the first place. Their article proposes a new model for design thinking based on the IDEO model but with three new foundational steps: reflect, democratize, and contextualize.

…the designer is not a neutral and objective expert.“Reflect” requires designers to examine their positionality, “the extent to which one is privileged or oppressed along different axes of identity” (Staton, Gordon, Kramer, & Valdez, 2016, p. 10). In this model, the designer is not a neutral and objective expert. As we learned in Chapter 2, we all act from our own set of cultural assumptions which “creates blind spots and opportunities to harm and/or exclude design partners with less structural power…” (Staton, Gordon, Kramer, & Valdez, 2016, p. 10). In addition to helping illuminate the potential for blind spots and exclusion, an understanding of the multiple positionalities on a design team can also show the potential for building understanding and inclusion among team members. The more we understand about ourselves, the more we can find points of contact with other people.

In my experience, the process of reflection is not a one-time act. If 70% of my iceberg of experiences and assumptions is subconscious, it’s safe to assume that identifying all of my blind spots is going to take time. Last week a good friend of mine invited me to an introductory seminar on dismantling racism he was attending. I thought, wow, this person teaches classes, including a session with my own students on this issue. He is also African American. What more does he have to learn? I brought this up with one of our mutual friends who said that she always gets something out of these sessions because there are so many different ways that our personal biases work—and in every session she finds another insight that helps her better understand her own biases. Reflecting on one’s positionality can help people understand that not having experienced something yourself doesn’t mean that that thing isn’t real, and that what is considered “normal” or “good” is not the same for everyone.

…all design occurs within economic and political systems that, over hundreds of years, have perpetuated unfair and unequal access to resources and opportunities. As we learned in Chapter 3, all design occurs within economic and political systems that, over hundreds of years, have perpetuated unfair and unequal access to resources and opportunities. In addition to helping team members identify their personal biases, reflection also allows team members to understand the unique experiences they bring to the process, and to uncover some of their limits and strengths. In “How does your positionality bias your epistemology,” David Takacs says that when we ask how who we are shapes what we know, we can also identify and value our own experiential and intellectual assets:

By respecting the unique life experiences that each student brings to the classroom—by asserting that the broadest set of experiences is crucial to help each of us understand the topic at hand as completely as possible—we empower all students as knowledge makers….Rather than “tolerating” difference, we move to respect difference, as difference helps us understand our own view—and thus the world itself—better. From respect, we move to celebration, as we come to cherish how diverse perspectives enable us to experience the world more richly and come to know ourselves more deeply. (Takacs, p. 28-29)

So how do you go about mapping your own positionality? Where do you even begin? While it’s not often that designers or most people in general undertake this kind of self-discovery, it is a common practice among researchers who study human relations, behavior, and health. What we have been referring to as positionality, most researchers call reflexivity. The Qualitative Research Guidelines Project from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation gives a succinct introduction to reflexivity. In it, you’ll find many similarities to what we talked about in Chapter 2 regarding culture and worldview. Reflexivity describes “an attitude of attending systematically to the context of knowledge construction, especially to the effect of the researcher, at every step of the research process” (Cohen & Crabtree, 2006). Many researchers try to prevent bias by working with a team rather than as an individual so that (often hidden) beliefs and values can be more easily identified and discussed or contested. They examine and describe their background and position (sometimes keeping a personal journal to reflect on their decisions), and include a summary of how their potential biases may have impacted their research in their reports and articles.

…the goal is to foster the kinds of dialog needed to uncover and discuss values, perspectives and assumptions. Designers can use similar methods, and since design thinking typically involves a team with different areas of expertise, there should be more opportunities to identify some of the beliefs and values that individuals bring into the process. [4] The goal in these exchanges between team members is not to come to some kind of consensus about what is or isn’t the right world view for each member to adopt. Instead, the goal is to foster the kinds of dialog needed to uncover and discuss values, perspectives, and assumptions.[5] For instance, if no one on the design team has had experience with poverty, they may not realize that many families cannot afford to purchase fresh foods and do not have access to a kitchen in which they can store and prepare fresh foods.

In the contextualizing step, designers examine the issue at hand in the context of ongoing “struggles for identity, culture, place, and power” (Staton, Gordon, Kramer, & Valdez, 2016, p. 10). In the example of a team working to come up with ideas to increase physical activity among kids, team members need to understand the context in which the kids live and how that context—economic, racial, gender—might impact their ability to exercise. Think back to Chapter 3, to what we learned about how cities and suburbs were built in the 20th and 21st centuries and how that continues to impact family wealth and neighborhood vitality. Today some children spend their afternoons at home alone until parents come home from work, and are not allowed outside during that time because their neighborhood is not safe. Contextualizing the design brief within the social and economic realities of the people you are designing for (and hopefully with, but more on that later), you will find constraints, but you will also find opportunities to create solutions that work for lots of different people and a chance to push your creativity own self-understanding further.

The next step, democratizing, challenges the notion of who gets to be the designer and who is designed for.[6] Rather than seeing the design team as designing for someone who needs their services to solve a problem they are facing, a democratized design process values all participants as co-designers and values community expertise and creativity.

Communities at the margins have been innovating as a matter of survival and in the work of liberation since time immemorial. The very work of navigating life between forces of exploitation, violence, and neglect requires ingenuity in devising solutions around dominant social structures” (Staton, Gordon, Kramer, & Valdez, 2016, p. 11).

…defining design as something a singularly creative person does and then gives to someone else is limiting, even for the “expert.” So what is the role for the traditional designer in a democratized design process? Designers bring resources, credibility, and influence…and offer a structured set of tools through which community members may focus their creative potential if they so choose. This is a big shift for designers who are generally trained to be the creative ones, and the ones with the creative ideas. But defining design as something a singularly creative person does and then gives to someone else is limiting, even for the “expert.” The designer loses an opportunity to develop new skills and learn from people with different knowledge. What some might see as limiting their creative process, others embrace as a chance to learn and grow.

What are the barriers and limitations to Design Thinking for Social Justice (DT for SJ)? Time, money, and lack of trust are all seen as barriers to a social justice approach to design thinking. There may not be enough time and money to see a collaborative design-thinking process through. The more participants, the more ideas generated. The more ideas generated, the more time it takes to develop and evaluate those ideas. Design professionals are paid for their time as part of their contract (with the institution or company that hires them to lead the process), but community experts are often asked to participate as volunteers. This financial barrier means that it’s more often middle and upper-middle income earners who can be part of co-design teams because they are able to take time off of work and hire someone to watch their kids. Some funders recognize this barrier and will pay for things like gift cards, stipends, baby-sitting, etc. But it’s most often only the professionals who are paid.

If there is no money in place to implement the ideas, has the exercise raised false hopes or wasted people’s time? Even if participants from marginalized communities are present, will they able to participate fully? Do they feel comfortable speaking out and offering their critiques of a professional’s ideas? Do they feel like their time is well spent and that there will be a concrete outcome that helps solve the problems they have helped to identify? If there is no money in place to implement the ideas, has the exercise raised false hopes or wasted people’s time? Sometimes the design process is seen as a way to generate ideas that can then be brought to funders for implementation grants, but there are no guarantees. Is the time and energy that people give to a design thinking exercise valuable even if the design itself cannot be implemented? The authors see value in the design process because of the tools and relationships that community members may tap into in the future, but note that, in order for this to work, there need to be relationships and networks that exist beyond any singular design exercise.

This adaptation of the IDEO framework takes on three of the big challenges of equity-driven design: First, the challenge of educating design professionals about the limits and strengths of their world views and experiences and about the value of diverse problem-solving teams. Second, the challenge of educating design professionals about the long-term patterns of disinvestment that underlie our society and all design problems. And finally, the information equity challenge, understanding whose knowledge counts and who must be part of design decision-making.

The additional steps added at the front end also have the potential to create a cascading effect on the steps that follow. How might the “inspiration” step, where the team frames the problem, change if people directly impacted by the problem are involved? As the team “contextualizes” the issue or problem, they may identify a different set of issues that need to be addressed. Having explored their own positionality/situatedness, they may be more open to ideas they may not have previously understood or valued. They may come to the ideation phase with the same brief, but may look at the same data and come up with radically different ideas on what should happen.

Who was involved in the process? Who benefited? And who was harmed?The authors do see a weakness of DT for SJ in the fact that individual DT processes cannot shift the huge economic and social barriers to equity. Individual design projects will never bring about the scale of changes needed to give everyone fair and just access to opportunities and resources. The authors propose that networks of designers and community members build relationships over time, look for new projects to collaborate on, and support each others’ work. Many such networks have emerged over the last ten years. Some are discipline-specific, while others, like the Design Justice Network (http://designjusticenetwork.org/), are interdisciplinary. As you read through their statements of principles, what do you think is directly linked to how the design process unfolds? What is linked to what gets designed in the first place? What is linked to who designs? Next read the story of how the principles were generated. Their Venn diagram poses three interrelated questions: Who was involved in the process? Who benefited? And who was harmed?[7] We will carry these three questions forward into the next chapter as we explore discipline-specific design practices and their relationships to equity.

Works Cited

Brown, T., Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review, (Winter). Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/design_thinking_for_social_innovation

Cohen D. D. & Crabtree, B. (2006, July). Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Qualitative Research Guidelines Project. Retrieved November 13, 2018, from http://www.qualres.org/HomeRefl-3703.html

Staton, B., Gordon, P., Kramer, J., & Valdez, L. (2016). From the technical to the political: Democratizing design thinking (Vol. Stream 5, Article no. 5-008). Presented at the From Contested Cities to Global Urban Justice, Madrid, Spain. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306107677_From_the_Technical_to_the_Political_Democratizing_Design_Thinking

Endnotes

- See “Design thinking origin story plus some of the people who made it all happen” at https://medium.com/@szczpanks/design-thinking-where-it-came-from-and-the-type-of-people-who-made-it-all-happen-dc3a05411e53 ↵

- See “Prototyping in Design Thinking: How to Avoid Six Common Pitfalls” available at https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/prototyping-in-design-thinking-how-to-avoid-six-common-pitfalls. ↵

- See “ABC Nightline - IDEO Shopping Cart” at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M66ZU2PCIcM ↵

- But this will depend on how safe people feel offering their opinions in the group. ↵

- See Reflexivity from the Qualitative Research Guidelines Project/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation at http://www.qualres.org/HomeRefl-3703.html ↵

- This is similar to the idea of co-operative design you read about in the article on the origins of design thinking. The terms participatory design and co-design are more commonly used today. ↵

- See “Generating Shared Principles from Design Justice” at http://designjusticenetwork.org/blog/2016/generating-shared-principles. ↵