6 The Freedom Fighters: A Case Study of Covid-19 and Settler Colonialism

Kathleen Mah

Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic has catalyzed new dynamics in social movements and protests, notably amplifying the activities of right-wing, white supremacist, and white nationalist groups in Canada. This paper examines how these movements, particularly the Freedom Fighters (FFs), are not merely a response to the pandemic but are deeply rooted in and perpetuate the structures of settler colonialism. Central to this discussion is the notion of the “presumed universal body,” which embodies the privileges of white, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied masculinities that have historically been entrenched in Canadian settler colonialism. The paper critiques the predominant biomedical focus of this presumed universal body during the Covid-19 pandemic. Arguing that it obscures the broader socio-cultural and historical factors that influence health disparities, particularly among Indigenous and marginalized communities. This study critically analyzes the intersection of right-wing activism and public health in Canada. It explores the role of the FFs in sustaining colonial legacies and their interaction with public health systems, considering the broader implications for settler colonialism in Canada. Through this examination, the paper aims to highlight how contemporary protests and public health approaches are intertwined with and reinforce ongoing colonial structures, affecting those deemed expendable within Canadian society.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has defined a new era of social movements and performances of protest. It has reinvigorated and given new meaning to protests of right-wing, white supremacist, and white nationalist groups. However, it is not the pandemic alone that is newly carving out an old social arena for the continuation of settler colonialism in Canada. In Canada, settler colonialism has long established comforts and privileges in the white, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied masculinities (which I will call the “ ‘presumed universal body”‘ for conciseness). Changing social awareness and activism around issues of race, space, class relations, and other intersectional issues have instilled deep feelings of alienation and precarity in those who are the presumed universal body, or those who share proximity to it, and thus benefit from its privileged position.

Many conversations around Covid-19 have revolved around its unequal impact on individuals who may be older or have co-morbidities. Though these characteristics are undoubtedly linked to increased risk of further morbidity as well as mortality,[1] conversations that only focus on the biomedical risk factors of Covid-19 miss how settler colonialism, culture, social inequalities, and history have shaped the lives of people in Canada. The sole focus on biomedical language and practices has a significant influence in shaping how society views the body, disease, and health, carrying important social and political implications.[2] In this way, the sole application of biomedical lenses risks misrepresenting or misunderstanding the social determinants of health. In reality, Covid-19 infection and death rates were higher among minority racial/ethnic groups[3] and those of lower socio-economic income.[4]

In countries like Canada, insufficient attention has been given to addressing the oppressive colonial structures that generate “social and material inequities resulting in health disparities” among Indigenous communities.[5] Throughout the pandemic, public health has consistently failed to acknowledge and address these differences, opting for a biomedical universal approach to health and care.[6] This failure to confront colonial structures in Canada reproduces a long historical pattern of displacement, violence, and the erosion of cultural and social identities of those who do not align with the presumed universal body. The result of this long history is systems and institutions that have been formed to serve only the presumed universal body. In the case of health and care, this has led to the exclusion of some groups from inclusion in the ‘public’ of public health. This renders some people expendable, like Indigenous peoples, to protect the ‘actual’ public.

Canada’s failure to embrace daily efforts of decolonization has allowed white supremacy and nationalism to thrive.[7] In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, a manifestation of white supremacy emerged in the form of freedom protests. The Freedom Fighters (FFs), who identified as anti-globalists and anti-mandate/anti-mask protestors, gained substantial and concerning support during Covid-19. Similarly to other right-wing movements, the FFs are deeply invested in whiteness, and the presumed universal body more broadly, all of which are rooted in the history of colonialism and are reactions against attempts to decolonize. Present social inequalities, in tandem with decreasing social solidarity, have encouraged expressions of anger and resentment to take on a renewed sense of urgency and prevalence[8] among those like the FFs who engage and implicate non-state actors in a form of necropolitics characterized as cultural necropolitics.[9]

Cultural necropolitics expands necropolitical power (state relations that “dictate who may live and who must die”[10]), and places it into the hands of individual non-state actors.[11] Cultural necropolitics allows groups like the FFs to be conceptualized as engaging in a ‘downsurgency’ that enacts violence on unwilling participants of populations made vulnerable,[12] which in the case of Canada has been helped greatly by the work of settler colonialism. State and non-state necropolitics are tied together and have far-reaching consequences for health, care, and the ongoing legacy of colonialism.

In this paper, I seek to critically engage with these consequences. I argue that social movements such as the FFs not only embody but also thrive within the contemporary settler colonial agenda. Through the orchestrated performance of protest and the concealment of structural violence within formal institutions like public health, these movements contribute to the perpetuation of a necropolitical state. It is this structure that marks minority groupsand Indigenous peoples as expendable. I will begin this chapter with a thorough analysis of the FFs and their contemporary role in sustaining colonialism in Canada. I will then turn to a brief discussion addressing how FFs and public health interact and establish a multi-directional flow of power, oppression, and privilege that greatly affects those deemed expendable. I will conclude with a broader conversation about what the pandemic, FFs and public health mean for settler colonialism in Canada.

This paper is based on research spanning four months, carried out between May and August 2021 in Western Canada with the FFs. The research employed a mixed-methods approach encompassing both online and offline components, combining interviews, participant observation, and the attendance of ‘Freedom Rallies.’ The moniker ‘Freedom Fighters’ serves as a self-assigned label for a group of anti-Globalist protestors, more commonly recognized during the Covid-19 pandemic as anti-mask and anti-mandate protestors.

I position myself strictly as an outsider to this group. While maintaining a stance of criticism towards the actions and perspectives associated with the movement, I also adopt a methodology of critical empathy.[13] This research approach enables the study of what may be considered ‘unsavoury’ populations, allowing for a balance between understanding individuals’ humanity, while also critiquing the potential harms they may inflict.[14] Despite grappling with the complexities of my work concerning this movement, I remain committed to comprehending the significance of recognizing shared humanity in all individuals, a practice foundational to the field of anthropology. It is crucial to note that my engagement with this movement does not attempt to make excuses for their actions, nor do I seek to endorse their beliefs. My objective is to refrain from vilifying or dehumanizing them, acknowledging the nuanced motivation of their actions within the larger conversation of settler colonialism in Canada.

The Freedom Fighters

The FFs assert that the attachment of ‘anti’ to their protests greatly misrepresent their cause, values, and beliefs. They often state that the prefix ‘anti’ denotes negative connotations of control. According to the FFs, they do not aim to dictate anyone’s actions, instead their objective is to communicate that mandates are unjust and lockdowns unconstitutional, because of the lack of demonstrable proof of the pandemic’s existence. Paradoxically, while positioning themselves as not being ‘anti’ anything, they frequently label themselves as anti-globalists.

In this way the FFs view themselves as simply just pro-freedom. It is this ‘freedom’ that is viewed to be an essential part of Canadian life. The FFs define this freedom as connected to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, often utilizing the document to justify unquestioned expression of these rights, despite how one’s actions may affect someone else. Their belief that the freedom protected in the Charter belongs to all people equally outlines their opposition to affirmative action, equity, or special interest groups. They deny the need to treat anyone differently and turn a blind eye to the ways in which freedom in Canada is coded as belonging to whiteness and masculinities. FFs are deeply rooted in white masculine supremacy, white nationalism, and collective nostalgia that instills a deep sentimental longing or wistful reflection for a better Canada of the past.

These sentiments are best captured by their stance as anti-globalists. As fervent opponents of ‘globalism,’ the FFs resist what they perceive to be the overarching ‘agenda’ of globalism. According to the FFs, globalism is a conspiracy put in place by the ‘globalists.’ FFs believeglobalists are “orchestrating and driving the globalisation agenda” to which these globalists “would include the heads of various multinational corporations, politicians, military and government officials, academics and even, as some believe, religious leaders.” FFs believe in a hidden agenda in which the “end goal of this process is the elimination of national and cultural autonomy, the global homogenisation of the world’’s population and the creation of a one world government or, as they would call it, a one world dictatorship.” They believe that the globalists represent a “‘large unelected foreign entity”‘ that seeks to destroy the free and just Canadian way of life by eroding freedom, generational private property, the American dream, and by indoctrinating children into ‘progressive’ agendas.

FFs embody the practices of anti-globalists via their strong sentiments of nationalism. Their movement is very hesitant toward immigration, foreign aid, and Canada’s role on the international stage, often discouraging immigration to Canada and wasted money on aid. They are also highly critical of the government, believing that the politicians are a part of the globalist agenda. FFs point to several plans, policies, and bills passed by or supported by the Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government as evidence for the existence of a globalist hidden agenda. Gregory, one of my interlocutors and prominent leader of the Saskatchewan arm of the movement, elaborated on this idea in an interview when responding to my question asking him to explain the movement’s views of globalism and other associated agendas:

the easiest way I can explain it to people is, you know, if you’ve read the Communist Manifesto, that’s essentially what sustainable development is, in a much broader sense and a much bigger, sort of fuller presentation. But [it] essentially, it reads the same way, it means the same thing. If you look at the 17 goals. It’s essentially controlling every aspect of your life, from not just a national perspective, but from a global governance perspective, where you have now an unelected foreign entity that’s creating policy that our governments have agreed to, and implementing in our nation. Why are we being governed by an unelected foreign entity that doesn’t have our best interests at heart? It’s this transformation of our world and somebody’s controlling all aspects of our life from, again, [this] global governance position.

Gregory elaborates on this kind of global governance as necessitated on the blind submission of citizens and the erosion of traditional Western structures of empowerment that value men as the breadwinners and women as the reproducers and the caregivers, locked in the private sphere:

But I mean, the globalist know what they’re doing (…) by weeding out masculinity, demonizing it, destroying the nuclear family or the idea of the nuclear family. There’s a lot of different things that are under attack so they can achieve their goals. Because if you have a country full of strong men, warrior type men, that will defend against, you know, [the] attack. That’s going to be a lot harder to manage than a country full of men who, you know, don’t see themselves in that role anymore. So [I just] think that this is all by design. And, and, and it’s an important part to their puzzle. (…) And so it’s all about control. It’s all about state control, or global control. So in order to do that, you have to have a submissive and compliant populace. And that’s- these are all mechanisms to do push that into the direction they needed to go.

There are several important aspects of Gregory’s answer. Firstly, he quite clearly defines a ‘we’ and an ‘other’. In his statement, “Why are we being governed by an unelected foreign entity that doesn’t have our best interests at heart?,” he marks categories of insider and outsider, assuming that the ‘we’ that are being governed by the unelected foreign entity all have the same interests. Gregory, as a white, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied, middle-class man is universalizing the experience of being ‘Canadian’ even in the space of conspiracy. He is homogenizing not only the movement, but the whole population of Canada, reproducing racist and violent assumptions of identity that have historically done the work of settler colonialism to silence those who do not fit the presumed universal body.

Building on this universalization, Gregory describes his understanding of freedom. For Gregory and many others in the movement, masculinity is an essential component of freedom. By singling out masculinity, specifically white masculinity, Gregory essentializes and universalizes experiences of freedom, placing them under a colonial lens, rendering them into that presumed universal body and homogenous definition. Gregory’s answer matches with the larger rhetoric of the FFs. The shaping and defining of freedom in this way endows the FFs with necropolitical power in that it gives them the ability to exert biopolitical power over others and assign value to the bodies of people.[15] FFs utilize freedom as the space to enact these powers because their collective understanding of freedom enables whiteness to dispense unequal power and consequently unequal death. For the FFs freedom is a “cultural artefact,”[16] a sustained institution in a society meant to achieve the goal of necropolitics: the continuation of a carceral experience of everyday life for those who have been colonized and the minorities who exist alongside them.

FFs’ understanding of freedom in Canada has been greatly challenged by the pandemic. They often articulate the belief that freedom has been eroded and challenged by the globalists who have used the pandemic as a tool to indoctrinate free peoples into their agenda and control them. This has increased the FFs’ deep emotional roots in right-wing populism (RWP).[17] Because RWP is a ‘thin centered ideology,’[18] meaning that it lacks any concrete or consistent ideological beliefs or values, it appeals to masses of ‘ordinary’ people who feel alienated from their governments. The FFs are drawn to this ideology, often referring to themselves as the only rational ordinary people left in Canada. This places them in a unique position that ultimately entangles privilege with perceived or lived precarity.

As the world has begun to challenge conceptions of health, life, and care based on the presumed universal body, collectives, like the FFs, who seek to normalize and benefit from the this presumed universal body, increasingly engage in processes of self-victimization and the practice of cultural necropolitics to justify their stances. Contradiction and ambiguity are innate to this kind of self-victimization. Networks of white masculine supremacy allow for a flexible sense of self and group—and it is this flexibility, combined with the unique intersectional position of groups like the FFs, that make up what I call the privileged (dis)enfranchised person.

It is important to approach this intersection and entanglement with caution, as the assumption that economic precarity produces radical right-wing movements is dangerous and false. Rather it is white middle-class persons who need to be held accountable for their role in the rise of RWP and the perpetuation of settler colonialism.[19] Though I agree with this assumption broadly, and though I do not pretend to know the exact demographics of the movements in its entirety, I do know that not all FFs are those born of pure privilege . It is true that most of those with whom I worked are visibly white and many were middle-class; however, FFs often consider themselves as financially and socially disenfranchised and alienated. Though this disenfranchisement may not necessarily be ‘real’ or may be exaggerated, what matters is not the truth of their disenfranchisement, what matters is that they feel that way. What makes something real is the feelings and emotions tied to it. FFs may not be ‘actually’ disadvantaged, especially in the ways they claim that their experiences are equivalent to Indigenous peoples in Canada, but their belief in it is what makes it real. These claims justify their actions and reproduce settler colonialism in Canada by attempting to rebalance the scales of power in favour of whiteness.

When asked, FFs would say they are one of, if not the most, oppressed groups in Canada. This sense of conflation can sometimes be laughable. During my fieldwork I heard over and over how the FFs were being persecuted the same way Indigenous people were during the era of residential schools. Though this may seem to be an outlandish claim, this process of conflation can cause the media and outsiders to lose sight of serious threat that the FFs represent. It can take away from efforts to oppose settler colonialism because it can become easy to write off movements like the FFs.

Yet, it feels as though the threat of the FFs it is being ignored. Directly following my project, I had articulated to my family that the group would only grow and their presence would become more prominent in the news and our lives. Five and a half months later the FFs formed what they called the “Freedom Convoy.” They held the city of Ottawa hostage for weeks, using trucks and other vehicles to gridlock the city’s downtown area. They demanded the end to mandates and terrorized the city to do so. The convoy ended with the Prime Minister Justin Trudeau invoking the Emergencies Act for the first time since its inception in 1988. The Emergencies Act, which replaced the War Measures Act, was intended to be used in situations when “public order emergencies, international emergencies and war emergencies are proclaimed” to protect the “safety and security of individuals, values of the body politic and the preservation of the sovereignty, security and territorial integrity of the state.”[20] Its use underscores that the government evaluated the movement to pose a serious threat.

The entanglement of privilege and precarity, whether it be real or imagined, makes the FFs privileged (dis)enfranchised persons. Though seemingly contradictory, this approach allows FFs to occupy systems of privilege while also reacting to their perceived (or real) disenfranchisement to enact their ‘justice’. It is the privileged (dis)enfranchised person who embodies modern settler colonialism because they can live in and reproduce privilege while denying its existence.

In the context of health and colonialism during the pandemic, the FFs’ position as the privileged (dis)enfranchised person sustains a position of power characterized by perceived disempowerment. The source of this disempowerment can be anyone from the government, to what FFs call the “woke left.” The FFs believe that their rightful position in society has been usurped by minority groups whom they perceive to be over-supported by initiatives like affirmative action, and other policies that support equity, diversity, and belonging. FFs’ response to this ‘disempowerment’ (again, whether real or imagined) leads collective responses characterized by aggrieved entitlement,[21] collective nostalgia, and victimhood,[22] all of which are rooted in the idea that privilege is something owed to the group, to the extent that they long for the ‘good old days’ when this was unquestioned.

Instead of locating the source of their disenfranchisement above, towards the elite and oppressive structures like racial capitalism which extract and harm everyone except the rich elite, they look below, towards those over whom they do have power. This is a troubling practice. FFs, whether they can admit it or not, do occupy a relatively high space in the social hierarchy in Canada. Though not all of them are white, or rich, or well-educated (even though many are), their involvement in the movement lends itself to a proximity to the white middle-class that positions them higher in the social hierarchy. Those upon whom the FFs look down become targets, and this has serious consequences for Indigenous peoples, minorities, and all those targeted by those who correspond to the presumed universal body in relation to their own sovereignty over their health, life, and death.

This is the process of cultural necropolitics to which the goal is to rectify their (dis)enfranchisement. This can vary greatly in the actions and discourse that it entails. One common example among the FFs during my study was the conflation of circumstances of the FFs’ experience during the Covid-19 pandemic. I look again to Gregory, as a leading voice in the movement, as an example of this. The following quotations come from a livestream Gregory hosted. The livestream followed the discovery of the unmarked graves of two hundred and fifteen Indigenous children on the site of a former residential school property, now on the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation:

We have been told that they have uncovered a mass grave site near Kamloops. 215 children discovered in a grave. And yes a horrible, it’s genocidal, it’s homicidal, it’s insane, it’s an atrocity and I am sure if we did that at similar residential schools across the country we would find similar atrocities that had taken place. (…) However, do not for a second allow the government, allow Trudeau, allow any of the public virtue signallers to blame you. You or I did not commit these atrocities.

Gregory goes on to elaborate on the “hypocrisy” of so-called “virtue-signallers,” who refuse to support the FFs. For Gregory and many other FFs, their protests seek to destabilize the very same structures of power that established residential schools:

The hypocrisy is absolutely astounding. Here we have a situation [that] happen[ed] decades ago. [Now], people are attempting to hold me and you accountable for it. We didn’t do it. The government did, their policies. The virtue signalling around it is astounding, the hypocrisy is astounding. Because right in front of our face, right now happening in real time, people have spent the last year ridiculing, shaming, dismissing people like myself, like you folks, for criticizing, questioning and holding responsible the government for what they have done to our lives, our livelihoods, our childhoods, our businesses, our schools, our sports teams, and everything that is attached to all of these measures that have been taken that they have yet been able to justify. And when we try to hold the government responsible, when we try force the government to show us their evidence, when we try to get the government to justify their actions while they destroy more lives than the illness itself has. The greater population stifles that. They shame us, they ridicule us for doing it.

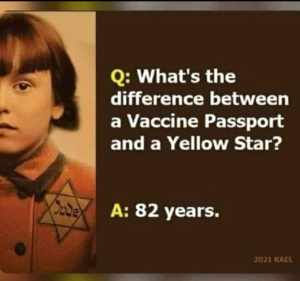

In order to stabilize their inherently contradictory existence, FFs utilize conflation and comparison like the above to justify their actions. This kind of conflation and ones like those depicted in Figure 1 change the discourse of freedom and oppression. Our post-pandemic meaning of freedom will be drastically different because of the co-optation of the word by groups like the FFs who embody white supremacy and white nationalism. Though beyond the scope of this paper to explore, it is still important to note that this may have possible ramifications for how we use ‘freedom’ in conversations around Indigenous sovereignty and other social justice issues. FFs carry contemporary colonialism with them in their refusal to wear masks, to isolate, and to vaccinate. Their inability to see beyond the structures of power that empower whiteness and their perceived (dis)enfranchisement attempt to undo the work of decolonialism. It’s not just about wearing a mask or not, it is about understanding the social circumstances and collective duty to others that recognize how some groups, in particular Indigenous people, have historically been on the receiving end of violence that puts them more at risk for illnesses like Covid-19. It is the lack of recognition of the social determinants of health that are at the heart of the FFs’ actions and their embodiment of the modern settler colonial agenda.

Public Health in Perspective

FFs are not alone in the perpetuation of colonialism during the Covid-19 pandemic. Public health and other formal governmental institutions need to be held accountable in tandem with the FFs. Though often positioned as opposing one another, I argue that the FFs and public health are united in their undertaking of settler colonialism in Canada. Both groups are united in shared deep structures that place white masculinity as privileged. Canada, as a direct product of colonial racial capitalism, founded a political system upon ideas of racial order and hierarchy.[23] Racial capitalism, as first defined by Cedric Robinson,[24] finds race at the centre of social and labour hierarchies in capitalist spaces. Canada’s history as a settler colonial society, built by racial capitalism, has changed the landscape of social and health inequalities and has only been exacerbated by Covid-19. Racial capitalism and settler colonialism have shaped how we work, live, and love.

Our social landscape ultimately affects our health. Those more at risk of dying due to Covid-19 are those with underlying comorbidities that should be considered as structurally established inequalities, and that exacerbate the risk of contracting and dying from Covid-19.[25] Meaning that those at most risk and those who have died in disproportional rates are those who have been defined as expendable through settler colonialism and racial capitalism. It is specifically Indigenous but also Black, Asian, and other minoritized people who have accounted for the majority of deaths during Covid-19.[26] These groups’ inability (and resistance) to align with the restrictions of whiteness in a settler-colonial world has led to the conception that some are expendable in order to protect the rest of the population.

When we look at the colonial history of Canada, it becomes easier to see why and how whiteness continues to drastically create health disparities between Indigenous peoples and racialized minorities, and the rest of the population. Colonial practices like those associated with eugenics have greatly influenced Indigenous health. The history of eugenics in Canada and the connection between it and public health is evident. Broadly, public health and eugenics are inherently connected. As the fields emerged, leaders in the two fields shared three key ideas: prevention, efficiency, and progress,[27] shaping the ideas that preventing disease was more efficient than curing it.[28] In Canada the overarching ideology that white men and women were morally, physically, and mentally fit, and that Indigenous men and women were ‘unfit’, was perpetuated. Helen MacMurchy, a Canadian doctor, pushed beliefs about heredity and public health’s role in protecting ‘society’.[29] MacMurchy believed that diseases reproduced and passed down by ‘mentally defective’ women produced paupers and criminals. She advocated for sterilization in order to deal with the burden of the mentally deficient and the threats that diseases posed to a healthy Canada.[30] In Alberta specifically, even feminism, shaped by agrarian lifestyles, contributed to significant lobbying to the provincial government, by white protestant women, many of whom were nurses or worked in associated care-giving fields, for eugenic legislation in the province.[31] The establishment of the Alberta Eugenics Board in 1928 reflected the idea that eugenics was a popular belief, not simply a niche practice.[32] In its lifespan from 1929-1972 the Alberta Eugenics Board sterilized over two thousand individuals, a disproportionate amount being Indigenous peoples.[33] Not only were Indigenous people disproportionately sterilized, they were also disproportionately deemed ‘mentally defective.’ This label allowed the Board to sterilize them without their consent.[34]

In the case of the pandemic, public health again, demonstrated its biased and systemically violent nature. Several Covid-19 policies that showed a lack of attention and care Indigenous peoples and others that exist ‘downward’ in the social hierarchy. The health initiatives of Covid-19 – wash your hands, social distance, and stay home – all reflect an assumption of a general social equality of access to all resources. Hand washing is not possible when one does not have access to clean water. Social distancing except for those who are ‘essential workers’ prioritizes profits over bodies and lives of workers in malls, retail, and the fast-food industry. Staying home does not work for the homeless and puts domestic violence victims at increased risk, effectively eliminating their social ties to safe spaces.[35] All of these spaces, where vulnerability effects ones exposure and risk to Covid-19 are racialized spaces created via settler-colonialism.[36] The assumption of equal access to safe and clean spaces justifies public health’s belief that they are serving all peoples, when in reality, this ignorance may exacerbate inequality.

Intersections of the FFs and Public Health

Public health and its historical connection to eugenics are only one small part of the picture. The eugenic practices employed only point to the structures of white supremacy in Canada, they do not establish them. Settler colonialism has not gone away, it exists as long as settlers continue to occupy the lands they ‘claimed,’ and as long as their ideologies of white supremacy prevail. Approaching settler colonialism, especially within the realm of decolonization of health, and of necropolitics and cultural necropolitics, is most useful when it is done holistically. It is therefore important to call into question not only the role of public health in the pandemic, and not just the role of the FFs in empowering the presumed universal body, but all of it, together, both historically and in the present.

Though I have argued that the FFs and public health are rooted in the same kind of structurally and systemically violent systems that settler-colonialism has made space for, I also believe understanding the way that these groups challenge each other while simultaneously supporting each other is an effective part of decolonial efforts. Throughout the pandemic, FFs and public health have been understood as in diametric opposition to each other; though this is not the whole story, this kind of tension, the tension between powers of whiteness and privilege destabilizes both.

There are many areas in which FFs showcase this tension. One of the most prominent is in how they feel public health has failed people during the pandemic. FFs feel very passionately about the loss of life in the elderly population and nursing homes. They are critical of the disregard for the protection of this portion of the population. FFs also have expressed on several occasions that home is not something safe for everyone. On a live stream, Gregory highlighted the rise in domestic violence experiences and deaths since lockdown measures were first implemented. He also touched on access to resources for people with addictions or other mental health concerns and the deaths occurring from isolation from resources.

Though FFs are good at critiquing the government they do not recognize their own participation in the reproduction of the very structures that they seek to critique. They often miss intersectional factors of racism, classism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, etc. And more often than not their critiques reiterate violent beliefs and ideologies that perpetuate white masculine privilege. For example, FFs often claim that vaccine passports are equal to segregation and an attempt to create “two classes of citizens” in which one has more rights than the other. They also often refer to police officers who give out tickets and participate in the arrest of protestors as ‘Nazis’. Their concerns get lost in the rhetoric of conspiracy and conflation, causing outsiders to reject any and all discourse that is produced by the FFs movement.

Within these interactions between public health and the FFs, real people have become a necessary loss for the ‘greater’ good. Survival of Covid-19 has been built on the graves of those who have been historically and presently rendered unimportant and a drain on the collective. In order to move forward, we must continue to question the structural and systemic violence around us. I believe that FFs make visible to many the kinds of power and oppression we cannot see in our everyday lives. Instead of attempting to pick sides in the feud between public health, the government and the FFs we should seek individual accountability and collective responsibility among all parties. FFs are not blameless; their role in the perpetuation of white supremacy during Covid-19 needs to be addressed. However, the process of undoing the FFs systems of unquestioned privilege is not mutually exclusive from the undoing of state violence. The contradiction of opposition and harmony between these groups is not a point of tension, but an entry into decolonization.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank Dr. Steve Ferzacca and Dr. Suzanne Lenon for their guidance on my research. I would also like to thank the Lethbridge Public Interest Research Group for their financial support of my work. Finally, I want to thank Tyler McCallum for his unwavering support.

- Ejaz, Hasan, Abdullah Alsrhani, Aizza Zafar, Humera Javed, Kashaf Junaid, Abualgasim E. Abdalla, Khalid O.A. Abosalif, Zeeshan Ahmed, and Sonia Younas. 2020. “COVID-19 and Comorbidities: Deleterious Impact on Infected Patients.” Journal of Infection and Public Health 13 (12): 1833–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.07.014. ↵

- Briggs, Charles L. 2005. “Communicability, Racial Discourse, and Disease.” Annual Review of Anthropology 34 (1): 269–91. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120618. ↵

- Boserup, Brad, Mark McKenney, and Adel Elkbuli. 2020. “Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Racial and Ethnic Minorities.” The American Surgeon 86 (12): 1615–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003134820973356;Wilder, Julius M. 2021. “The Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the United States.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 72 (4): 707. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa959. ↵

- Pongou, Roland, Bright Opoku Ahinkorah, Marie Christelle Mabeu, Arunika Agarwal, Stéphanie Maltais, Aissata Boubacar Moumouni, and Sanni Yaya. 2023. “Identity and COVID-19 in Canada: Gender, Ethnicity, and Minority Status.” PLOS Global Public Health 3 (5): e0001156–e0001156. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001156. ↵

- de Leeuw, Sarah. Nicole M. Lindsay, and Margo Greenwood. 2015. “Introduction: Rethinking Determinants of Indigenous People’s Health in Canada”. In Determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ Helath in Canada: Beyond the Social. Edited by Margo Greenwood, Sarah de Leeuw, Nicole M. Lindsay, Charlotte Reading. Canadian Scholars Press. Toronto, Ontario. ↵

- Kinsmen, Gary. 2020. “Learning from AIDS Activism for Surviving the COVID-19 Pandemic.” In Sick of the System: Why the Covid-19 Recovery Must Be Revolutionary, 173–95. Between the Lines Press. ↵

- Hunt, Sarah, and Cindy Holmes. 2015. “Everyday Decolonization: Living a Decolonizing Queer Politics.” Journal of Lesbian Studies 19 (2): 154–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2015.970975. ↵

- Salmela, Mikko, and Christian von Scheve. 2017. “Emotional Roots of Right-Wing Political Populism. Social Science Information.” Social Science Information 56 (4): 567–95. ↵

- Bratich, Jack. 2021. “‘Give Me Liberty or Give Me Covid!’: Anti-Lockdown Protests as Necropopulist Downsurgency.” Cultural Studies 35 (2–3): 416–31. ↵

- Mbembe, J.A. 2003. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15 (1): 11–40. ↵

- Bratich, Jack. 2021. “‘Give Me Liberty or Give Me Covid!’: Anti-Lockdown Protests as Necropopulist Downsurgency.” Cultural Studies 35 (2–3): 416–31. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Coning, Alexis de. 2023. “Seven Theses on Critical Empathy: A Methodological Framework for ‘Unsavory’ Populations.” Qualitative Research : QR 23 (2): 217–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687941211019563. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Mbembe, J.A. 2003. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15 (1): 11–40. ↵

- Santiáñez, Nil. 2021. “Necropolitics and Culture; or the Embedding of Cultural Practices in Necropower.” University of Toronto Quarterly 90 (4): 691–712. ↵

- Salmela, Mikko, and Christian von Scheve. 2017. “Emotional Roots of Right-Wing Political Populism. Social Science Information.” Social Science Information 56 (4): 567–95. ↵

- Erl, Chris. 2020. “The People and The Nation: The ‘Thick’ and ‘Thin’ of Right-Wing Populism in Canada.” Social Science Quarterly 102 (1): 107–24. ↵

- Bhambra, Gurminder K. 2017. “Brexit, Trump, and ‘Methodological Whiteness’: On the Misrecognition of Race and Class.” The British Journal of Sociology 68 (1): 214–32. ↵

- Niemczak, Peter & Phillip Rosen. 2001. “Emergencies Act”. Law and Government Division. https://publications.gc.ca/Collection-R/LoPBdP/BP/prb0114-e.htm#:~:text=The Emergencies Act(2) sets,Assent on 21 July 1988. ↵

- Kimmel, Michael S. 2013. Angry White Men : American Masculinity at the End of an Era. American Masculinity at the End of an Era. New York, NY: Nation Books, a member of the Perseus Books Group; Thorburn, Joshua, Anastasia Powell, and Peter Chambers. 2023. “A World Alone: Masculinities, Humiliation and Aggrieved Entitlement on an Incel Forum.” British Journal of Criminology 63 (1): 238–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azac020. ↵

- Wilson, Chris. 2022. “Nostalgia, Entitlement and Victimhood: The Synergy of White Genocide and Misogyny.” Terrorism and Political Violence 34 (8): 1810–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2020.1839428. Wohl, Michael J.A., Anna Stefaniak, and Anouk Smeekes. 2020. “Longing Is in the Memory of the Beholder: Collective Nostalgia Content Determines the Method Members Will Support to Make Their Group Great Again.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 91 (11): 104044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2020.104044. ↵

- Toews, Owen. 2012. “Stolen City: Racial Capitalism and the Making of Winnipeg”. ARP Books, Winnipeg Manitoba. 14-100. ↵

- Robinson, Cedric J. 2000. “Black Marxism: the Making of the Black Radical Tradition”. Chapel Hill, N.C. University of North Carolina Press. ↵

- McClure, Elizabeth S, Pavithra Vasudevan, Zinzi Bailey, Snehal Patel, Whitney R Robinson. 2020. “Racial Capitalism Within Public Health—How Occupational Settings Drive COVID-19 Disparities”. American Journal of Epidemiology. 189(11): 1244–1253. ↵

- Clarke, John. 2021. “Following the Science? Covid-19, ‘Race’ and the Politics of Knowing.” Cultural Studies 35 (2–3): 248–56; Magesh, Shruti, Daniel John, Wei Tse Li, Yuxiang Li, Aidan Mattingly-app, Sharad Jain, Eric Y. Chang, and Weg M. Ongkeko. 2021. “Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” JAMA Network Open 4 (11): e2134147–e2134147. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34147. ↵

- Lombardo, Paul. 2019. “Eugenics and Public Health: Historical Connections and Ethical Implications.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Health Ethics, Edited by Anna C. Mastroianni, Jeffery P. Khan, and Nancy E Kass. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- McLauren, Angus. 1990. Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada 1885-1945. Toronto, Ontario: McClelland & Stewart Inc. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Kurbegović, Erna. 2016. “Eugenics in Canada: A Historiographical Survey.” Acta Historiae Medicinae, Stomatologiae, Pharmaciae, Medicinae Veterinariae 35 (35): 63–73. https://doi.org/10.25106/ahm.2016.0912. ↵

- Grekul, Jana, Arvey Krahn, and Dave Odynak. 2004. “Sterilizing the ‘Feeble-Minded’: Eugenics in Alberta, Canada, 1929-1972.” Journal of Historical Sociology 17 (4): 358–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6443.2004.00237.x. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- McLauren, Angus. 1990. Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada 1885-1945. Toronto, Ontario: McClelland & Stewart Inc. ↵

- Kinsmen, Gary. 2020. “Learning from AIDS Activism for Surviving the COVID-19 Pandemic.” In In Sick of the System: Why the Covid-19 Recovery Must Be Revolutionary, 173–95. Between the Lines Press. ↵

- Ibid. ↵