2 Case Study on William Brown and Thomas Gilmore’s letter to William Dunlap, 1768: Connecting Territory Network Methodology to the History of Slavery in Canada

Emily Davidson

Abstract

Slavery was a key imperial colonial institution in the territories that became Canada but the intertwined nature of slavery and settler colonialism remains an underdeveloped sub-field of both Canadian settler colonial studies and Canadian slavery studies. This essay examines the 1768 correspondence sent by the Quebec Gazette proprietors William Brown and Thomas Gilmore to their former employer William Dunlap, a printer in Philadelphia. The letter first details settling financial accounts between the men, and then makes a request for Dunlap to purchase and send an enslaved person to Quebec on behalf of Brown and Gilmore, to be forced to work in their printing office. I use the methodology of reading against the grain to produce a historical analysis of the letter’s content and context.

To position this historical document in a decolonial framework, I use a methodology I name Territory Network Methodology to trace the network of Indigenous territories and colonial metropole locations connected to this correspondence. This method reveals how the complex global networks required to produce everyday objects extends far beyond the conception of place and land normally attributed to objects under colonial capitalism. This framework insists on, and reveals, the continuous and contemporary sovereignty of Indigenous people and territories.

Introduction

Race-based slavery was a key imperial colonial institution in the territories that became Canada, but the intertwined nature of Transatlantic slavery and settler colonialism remain underdeveloped sub-fields of both Canadian settler colonial studies and Canadian slavery studies.[1] In order to think through Canada’s history of slavery within a decolonial framework, an examination of how settler occupation and dispossession of Indigenous territories operated in tandem with practices of slavery is required. This case study represents a preliminary effort to use Territorial Network Methodology to examine the April 1768 correspondence sent by Quebec Gazette proprietors William Brown and Thomas Gilmore to their former employer William Dunlap to request that he purchase and send an enslaved person to them, to be forced to work in their printing office.[2] This method reveals how land is inextricable from the complex global networks of colonialism, imperialism and Transatlantic slavery and situates my analysis of historic colonialism within a framework that insists on the continuous and contemporary sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples and the territories they have stewarded since time immemorial. This case study outlines the utility of Territory Network Methodology for the study of historic documents, however, additional extensive inquiry is required to approach the level of detail and complexity required to fully map and analyze the territories connected to Brown and Gilmore’s April 1768 letter.

Slavery in the Territories that Became Canada

Colonizers enslaved both Black[3] and Indigenous Peoples in the territories that became Canada from the early 1600’s until 1834.[4] As the art historian Charmaine A. Nelson reminds us, “the forced importation of Africans for labour was an integral part of Canada’s colonial origins and nation building project, by both British and French colonizers.”[5] During this over 200-year period, chattel slavery was implemented by French colonizers in the territories they occupied as New France from the early 1600s until the cession of New France to Britain and Spain in 1763 through the Treaty of Paris, at the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War. Colonizers in New France enslaved Indigenous Peoples in—and removed them from—their homelands, with a large percentage of the enslaved Indigenous population being from the Pawnee Nation, whose territory is currently occupied by the United States (as the states of Nebraska, Oklahoma and Kansas).[6] People of African descent were also enslaved by colonizers in New France, with the first documented instance being in 1629, when British trader Sir David Kirke imported a child from either Madagascar or Guinea as a chattel slave.[7] French colonizers entrenched the practice of race-based slavery into colonial law with the official authorization to import enslaved Black people to New France by French King Louis XIV in 1689,[8] the Ordinance Rendered on the Subject of the Negroes and the Indians called Panis[9] in 1709,[10] and additional proclamations regarding slavery by French King Louis XV in the 1720s and 1745.[11]

When British colonizers claimed territorial control of New France in 1760, the Articles of Capitulation included a specific clause on enslavement. Article XLVII stated:

The Negroes and panis of both sexes shall remain, in their quality of slaves, in the possession of the French and Canadians to whom they belong; they shall be at liberty to keep them in their service in the colony, or to sell them; and they may also continue to bring them up in the Roman Religion.[12]

The British Royal Proclamation 1763[13] established the colonial Province of Quebec on the territories ceded by France to Britain at the Treaty of Paris, and expanded the area in which British colonizers practiced chattel slavery. As early as 1749, British colonizers imported enslaved Black people in the colony of Nova Scotia.[14] In 1750, 418 of the nearly 3000 inhabitants of Halifax were enslaved people.[15] After the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War in 1783, British colonizers significantly increased the practice of slavery in British North America. After the Imperial Statute of 1790 was passed, approximately 3,000 enslaved men, women and children of African descent were forcibly relocated to the colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland, Upper Canada and Lower Canada by white Loyalist colonizers.[16] In 1834, the Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies; for promoting the Industry of the manumitted slaves; and for compensating the Persons hitherto entitled to the Service of such Slaves[17] came into effect in all territories occupied by the British Empire including British North America.[18] However, for most enslaved people in British North America, emancipation under the Slavery Abolition Act resulted only in partial liberation. The Slavery Abolition Act permitted enslavers to retain formerly enslaved people over the age of six for four to six years as apprentices, granting immediate emancipation only to those under the age of six.[19] Additionally, indentureship was supported by legislation and practiced throughout British North America leading up to, and continuing after, the enactment of the Slavery Abolition Act.[20] The British Empire, including British North American colonies, continued to benefit economically from trade with territories practicing slavery throughout most of the nineteenth century,[21] with Brazil being the last territory to pass a statute officially abolishing slavery in 1888.[22]

Territory Network Methodology

In this essay I aim to introduce and apply a methodology I am currently developing, which I name Territory Network Methodology, to the study of historic documents.[23] The basic premise of Territory Network Methodology is to reveal the complex network of land and place connected to a specific object. This methodology expands the notion of land acknowledgement[24] and runs parallel to many Indigenous-led mapping projects[25] and intercultural collaborations aiming to center Indigenous place names and visualize Indigenous territories.[26] Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination guide the parameters I put in place to develop this methodology.

Territory Network Methodology aims to use the self-determined names for places and people. The Māori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith writes that “by ‘naming the world’ people name their realities”[27] and notes that “there are realities which can only be found, as self-evident concepts, in the indigenous language; they can never be captured by another language.”[28] I therefore seek nation-specific Indigenous-authored sources to learn the names of Indigenous nations and places.[29] In some cases, Indigenous nations have re/claimed place names created by colonial-Indigenous interactions and use these names in contemporary and self-determined ways.[30] In other cases, my exclusive reliance on English language resources, combined with the colonial erasure of Indigenous naming, limited my access to self-determined names of some peoples and territories. For colonial metropole sites, I also used self-determined place names but did not seek information on “original” non-Indigenous inhabitants. Casting everyone as “Indigenous to somewhere” ignores the realities of metropole-colony empire and operates as, what Unangax scholar Eve Tuck and frequent collaborator K. Wayne Yang term, a “settler move to innocence”[31] to allow colonizers to avoid responsibility for colonization.

Territory Network Methodology resists the urge to flatten complexities into matching information categories across all sites. This acknowledges that Indigenous ways of naming homelands differ around the world.[32] The practice of replacing a settler place name for an Indigenous place name[33] effectively insists on the continuity of Indigenous place-making and territorial stewardship, but can be limited by an underlying (settler) assumption that every colonizer settlement has an analogous Indigenous name.[34] This assumption erases the fact that settler and Indigenous place naming practices often differ in purpose and scope and carry nation-specific cultural meanings and land knowledges.[35] For example, on difference between colonizer and Mi’gmaw[36] place names, the Gespe’gewa’gi Mi’gmawei Mawiomi write: “our naming of places is strikingly different from the way invaders from Europe renamed our territories.”[37] Additionally, name replacement frequently flattens complexities such as contested or overlapping Indigenous territories and places—especially gathering places—named in multiple Indigenous languages. Instead, Territory Network Methodology aims to make visible the unruly complexities of overlapping/contested/co-existent/imposed/continuous territories.[38] In order to work in parallel with Indigenous sovereignties, territory network methodology aims to recognize ongoing relations, obligations, responsibilities and accountabilities specific Indigenous Nations have to maintain territories.[39] Within this text, I aim to make this unruliness apparent by using multiple place names strung together[40] with brief descriptions of overlapping areas and occupations.

Reading Against the Grain

In this essay I will attend to the complexities of the colonial archive by reading “against the grain” to examine an enslaver-produced primary source document.[41] This method involves close reading and of analysis of archival documents to scrutinized the often-unexamined biases of enslaver and colonizer produced materials. Reading “against the grain” reveals how power structures undergird colonial archives and offers opportunities to recontextualize archival materials within liberatory and decolonial frameworks. I follow the scholarship of Transatlantic slavery scholars Charmaine A. Nelson, Marisa J. Fuentes, and Harvey Amani Whitfield aimed at filling “out the silences inherent to the archives of slavery.”[42] This method offers a nuanced approach to contextualize and excavate “an archive that rarely allows slaves to speak for themselves unless mediated through the pen of a white person.”[43] Nelson argues for the reconsideration of:

the fugitive slave archive not merely as a record of oppression, but as a means of recuperating the pervasive resistance of the enslaved, reading between the lines to recuperate their voices, lives, cultures, and aspirations for freedom.[44]

In this case, I expand on Nelson’s scholarship on William Brown and Thomas Gilmore’s April 1768 letter,[45] making an effort to surface the Black enslaved man Priamus from the fragments of his story that persist in archived enslaver-produced correspondence. By applying both “against the grain” reading and Territory Network Methodology to the study of historical documents, I hope to produce a robust analysis that contends with some of the gaps and contradictions in the (Eurocentric) study of Transatlantic slavery and settler colonialism in Canada.

Understanding Brown and Gilmore’s April 1768 letter

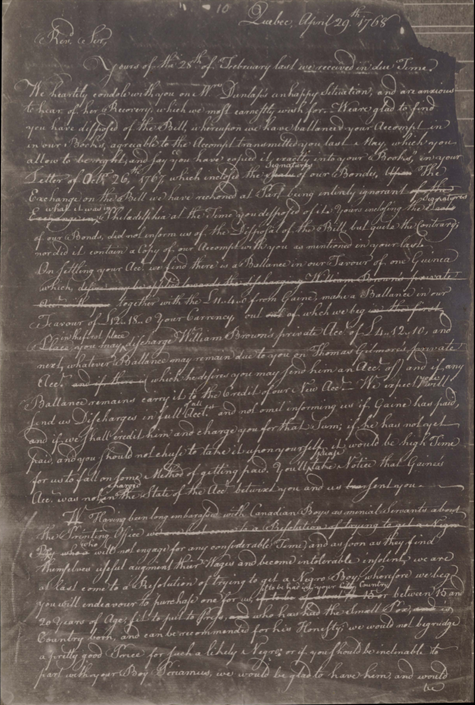

On April 29, 1768, William Brown and Thomas Gilmore sent a letter from Québec to Philadelphia aiming to reach[46] William Dunlap. Said another way, on April 29, 1768, Scottish[47] settler William Brown and Irish[48] settler Thomas Gilmore, who were occupying[49] Nionwentsïo, the Wendat territory, near Wendake and the overlapping southern region of Innu territory, Nitassinan, sent a letter to settler-occupied Coaquannock in Lenapehoking, the Lenape homeland, aiming to reach Irish[50] settler William Dunlap.

The April 1768 letter that Brown and Gilmore wrote to Dunlap provides a unique window into the mentality and modality of mid-eighteenth-century enslavers in the British Province of Québec. This British colony was officially imposed by the Royal Proclamation of 1763[51] onto multiple Indigenous territories stewarded since time immemorial by the Abenaki Nation, the Anishinabek Nation, the Atikamekw Nation, the Innu Nation, the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation, the Mi’kmaq Nation, the Wendat Nation, and the Wolastoqiyik Nation. The correspondence begins by Brown and Gilmore relaying condolences to William Dunlap about his wife, Deborah Dunlap’s, “unhappy Situation”[52] and sending wishes for her recovery.[53] After this friendly and courteous opening, Brown and Gilmore detail the settling of finances between the parties. Next, Brown and Gilmore introduce their problem: they are not satisfied with the “Canadian Boys”[54] (settlers of French descent) they have contracted into low-level positions during their first five years of running a printing office in the city of Québec/settler-occupied Nionwentsïo, the Wendat territory, near Wendake/settler-occupied Nitassinan, the Innu territory, writing:

Having been long embarrassed with Canadian Boys as menial Servants about The Printing Office who will not engage for any considerable Time and as soon as they find themselves useful augment their Wages and become intolerable insolent.[55]

Interestingly, Brown and Gilmore’s frustration with the “Canadian Boys”[56] (settlers of French descent) for not enduring their subjection in entry-level printing trade positions seems to run deeper than a concern for the profitability of their business. While Brown and Gilmore’s term “menial Servants”[57] could indicate that they are discussing labourers performing exclusively low-skill jobs within their enterprise, their description “as soon as they find themselves useful”[58] indicates that at least some trade-specific skills were being acquired by their workers—and with that a desire for higher compensation. Brown and Gilmore’s characterization of the French-Canadian workers in their employ as “intolerable insolent”[59] for seeking ways to use newly acquired trade skills to improve their livelihoods points to their deep social commitment to the entrenched hierarchies of the printing trade,[60] which is echoed by their formal valediction, “We are, with profound Respect, Sir, your most obliged humbled servants.”[61] Rather than adapting their business model to the conditions of the available workforce in the city of Québec/settler-occupied Nionwentsïo, the Wendat territory, near Wendake/settler-occupied Nitassinan, the Innu territory, Brown and Gilmore apparently desired to maximize their profit margin and ensure the maintenance of strict hierarchies within their printing office by owning the body and labour of “a Negro Boy,”[62] whom they can force to work without wages in perpetuity. They write:

we are at last come to a Resolution of trying to get a Negro Boy, wherefore we beg you will endeavor to purchase one for us, if to be had in your City, Country between 15 and 20 Years of Age, fit to put to Press, who has had the Small Pox, is Country born, and can be recommended for his Honesty[.][63]

This idealized list of traits of detailing the characteristics that would make an enslaved person most “useful”[64] “about The Printing Office”[65] gives insight into the value system of these two would-be enslavers and their belief in white supremacist racial hierarchies. To this end, Nelson’s concise analysis of this letter is helpful to my assessment:

The description offered by Brown and Gilmore was precise and detailed. While the mention of smallpox reveals slave owner preoccupation with the health and mortality of their enslaved laborers, it also underscores the commodification of labor that was at the heart of slavery. Their preoccupation for the male’s fitness and age highlights the demands of the intellectual and physical nature of the work to which they intended to set their new “Negro Boy.” While the request that Dunlap’s choice be honest was of obvious relevance to any slave owner, the request that the Black boy also be ‘country born’ demonstrates the White preference for Creoles, Blacks who, through their birth in the Americas, were deemed to be ‘seasoned’ and less resistant.[66]

Brown and Gilmore’s letter goes on to offer another possible solution for Dunlap to fulfil their request: that he sell them the enslaved man Priamus, whom he owns and has forced to work in his printing office. They write:

or if you should be inclinable to part with your Boy Priamus, we would be glad to have him, and would be willing to give what might be judged a reasonable Price[.][67]

Invoking the sale of Priamus as an option, may indicate that he fit some or all of Brown and Gilmores’s listed specifications, or that their list of traits was based, at least in part, on his personal characteristics. However, considering Priamus as an alternative to a “Negro Boy” of their preferred description, his mention may only indicate that he was a known entity to them, rather than that he categorically fit their listed traits. Brown and Gilmore clearly had level of familiarity with Dunlap’s enslaving practices and their knowledge of Priamus, specifically, indicates that he was likely enslaved in Dunlap’s printing office during the period Brown and Gilmore apprenticed and worked there from 1758 to 1763.[68]

Brown and Gilmore frame Priamus, an enslaved man they must have known personally, as a commodity, but their stated desire to own Priamus specifically reveals how non-interchangeable his talents, capabilities and skilled labour really were. While members of the enslaving class insisted upon the lack of intelligence and humanity of people of African descent, these claims were inadvertently undermined by their exploitation of the uniquely human talents of the people they enslaved, in particular by forced labour in the skilled trades. In this way, Brown and Gilmore’s letter reveals a similar irony to that described by Nelson, whereby fugitive slave “advertisements worked against the interests of the slave holding classes who, in their determination to recuperate their “property,” disclosed evidence of the corporal punishment to which the enslaved have been subjected.”[69]

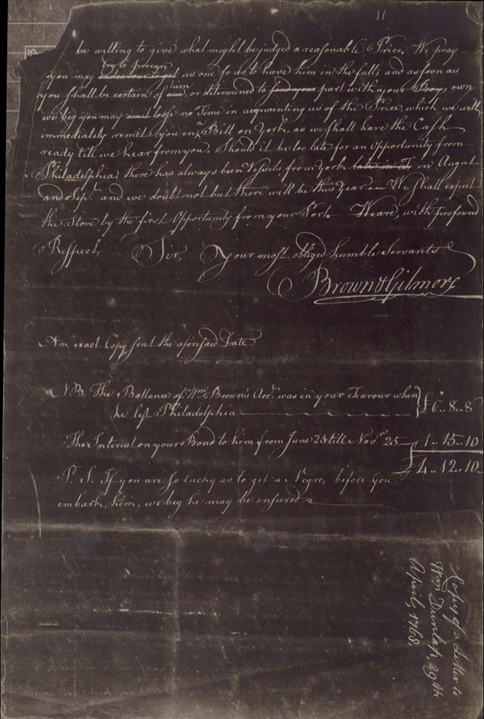

The monetary value Brown and Gilmore place on the person they intend to enslave supports Nelson’s concept that they planned to exploit the “intellectual and physical”[70] talents of that person by forcing him into some level of skilled labour. Of someone matching their list of preferred attributes they write, “we would not begrudge you a pretty good Price for such a likely Negro,”[71] here using the turn of phrase “likely”—a positive, yet condescending, term that was widespread in contemporaneous slave sale advertisements.[72] Of Priamus, they write that they “would be willing to give what might be judged a reasonable Price”[73] indicating that cash value put on Priamus may be higher than other untrained or unskilled enslaved people, but deferring to Dunlap’s valuation of his “commodity.” Brown and Gilmore’s post script, “If you are so lucky as to get a Negro, before you embark him, we beg he may be insured”[74] also ties into the valuation of the person they intend to enslave. Like their desire to own a person who has been inoculated against small pox, and would therefore survive an outbreak,[75] they sought to protect their investment through insurance.

The final portion of Brown and Gilmore’s letter describes, with some urgency, possibilities for shipping the enslaved person they have requested. They write:

We pray you may try to procure us one so as to have him in the fall, and as soon as you shall be certain of him, or determined to part with your own we beg you may loose [sic] no Time in acquainting us of the Price, which we will immediately remit you in a Bill on York, as we shall have the Cash ready till we hear from you. Should it be too late for an Opportunity from Philadelphia, there has always been Vessels from York in August and Sept. and we doubt not but there will be this year.[76]

This tone of urgency indicates not only their desire to extract wealth from enslaved labour at the earliest opportunity, but speaks to seasonal limitations[77] for shipping between the port of Philadelphia/settler-occupied Coaquannock in Lenapehoking, the Lenape homeland and the port of Québec/settler-occupied Nionwentsïo, the Wendat territory, near Wendake/settler-occupied Nitassinan, the Innu territory. Additionally, reading this letter in context of correspondence between Brown and Gilmore and Dunlap—and later his nephew John Dunlap[78]—between 1763 and 1771, the trade of goods between these men sometimes dragged out over years, as was the case with the stove ordered by Brown and Gilmore, which is also referenced at the close of this letter.[79] Frustration over the delay on their stove order may have contributed to their hastening Dunlap to “loose no Time”[80] in attending to their request for him to sell and send them an enslaved person.

The response to Brown and Gilmore’s request came not from William Dunlap, but from John Dunlap, who was in the process of purchasing and taking over his uncle’s printing office.[81] In J. Dunlap’s September 15, 1768 response, he makes no specific mention of fulfilling the request to send an enslaved person, but does promise to “settle that Part of your Mr. Dunlap’s Business which now is unsettled,”[82] which may indicate that he later coordinated the purchase and transport of an enslaved person on behalf of Brown and Gilmore.

Proposing Territory Network Methodology for Historical Biography

The “common sense” tone of Brown and Gilmore’s April 1768 correspondence belies the extreme violence of Transatlantic slavery and settler colonialism, institutions which they propelled and benefited from as colonial printers.[83] I argue that Brown and Gilmore’s enslaver “common sense” was formed through their place-specific interactions in multiple transatlantic locations. In order to unpack the enslaver world-view, recognition of the way colonizers sought to own both people and land is crucial. Eve Tuck and collaborators Allison Guess and Hannah Sulton of the Black/Land Project argue that “remaking of land and bodies into property is necessary for settlement onto other people’s land.”[84] Indeed, European colonial settlement in the Americas was predicated on enmeshed and co-constituting forms of violence: land dispossession, genocide and enslavement of Indigenous Peoples coupled with importation and enslavement of African people and their descendants in perpetuity. The Black feminist scholar Robyn Maynard, in collaboration with the Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, asserts:

the massive destruction, gendered and murderous, of (Indigenous) human life and land dispossession; the commodification, exploitation and fungibility of (Black) human life; and the relentless expropriation and destruction of non-human nature are inextricably linked: a disregard for all living things except for their value as property to be accumulated.[85]

The staggering scale of destruction, global reach, and temporal longevity of European imperial and colonial violence should not dissuade interrogation of place-and-time-specific manifestations of these systems.

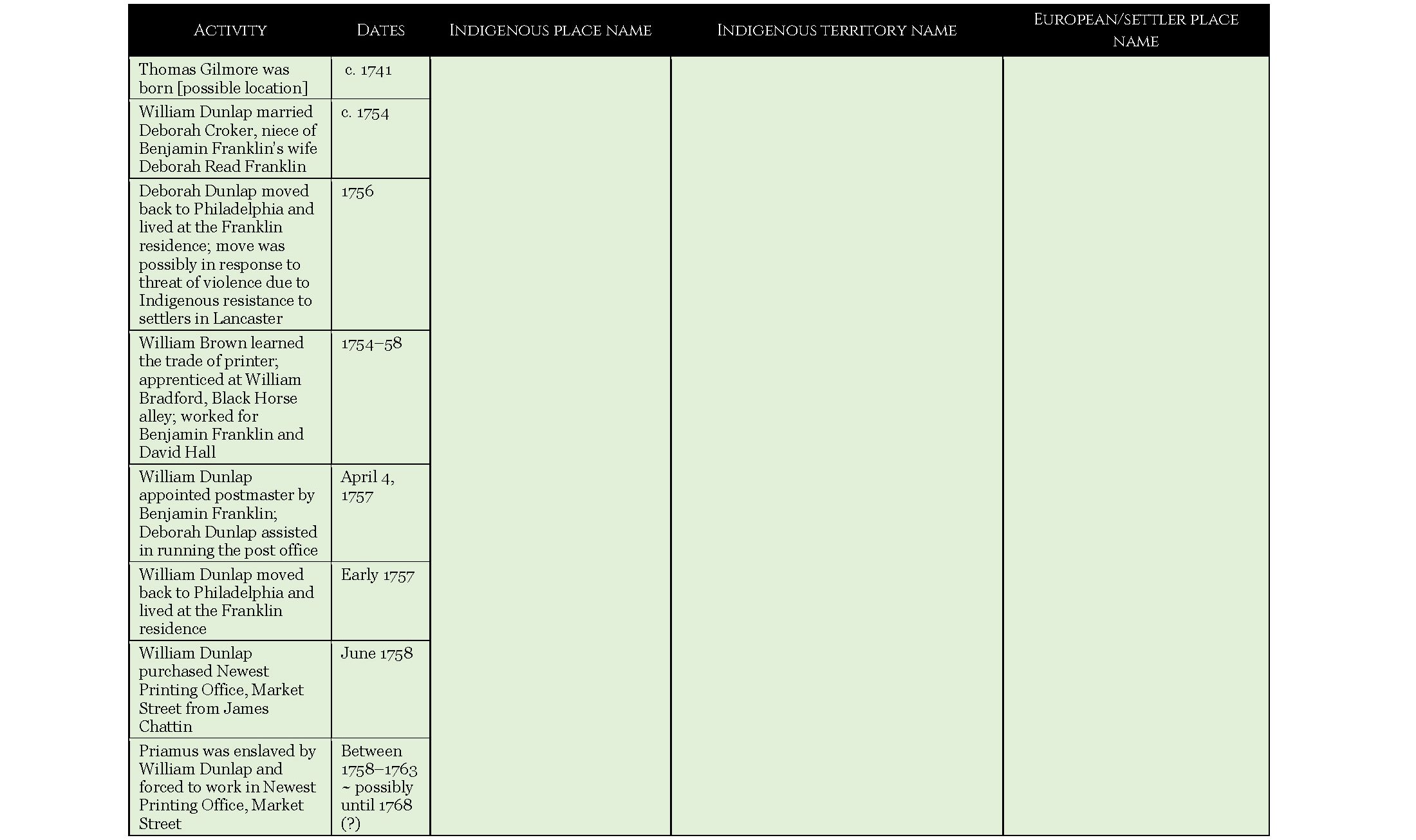

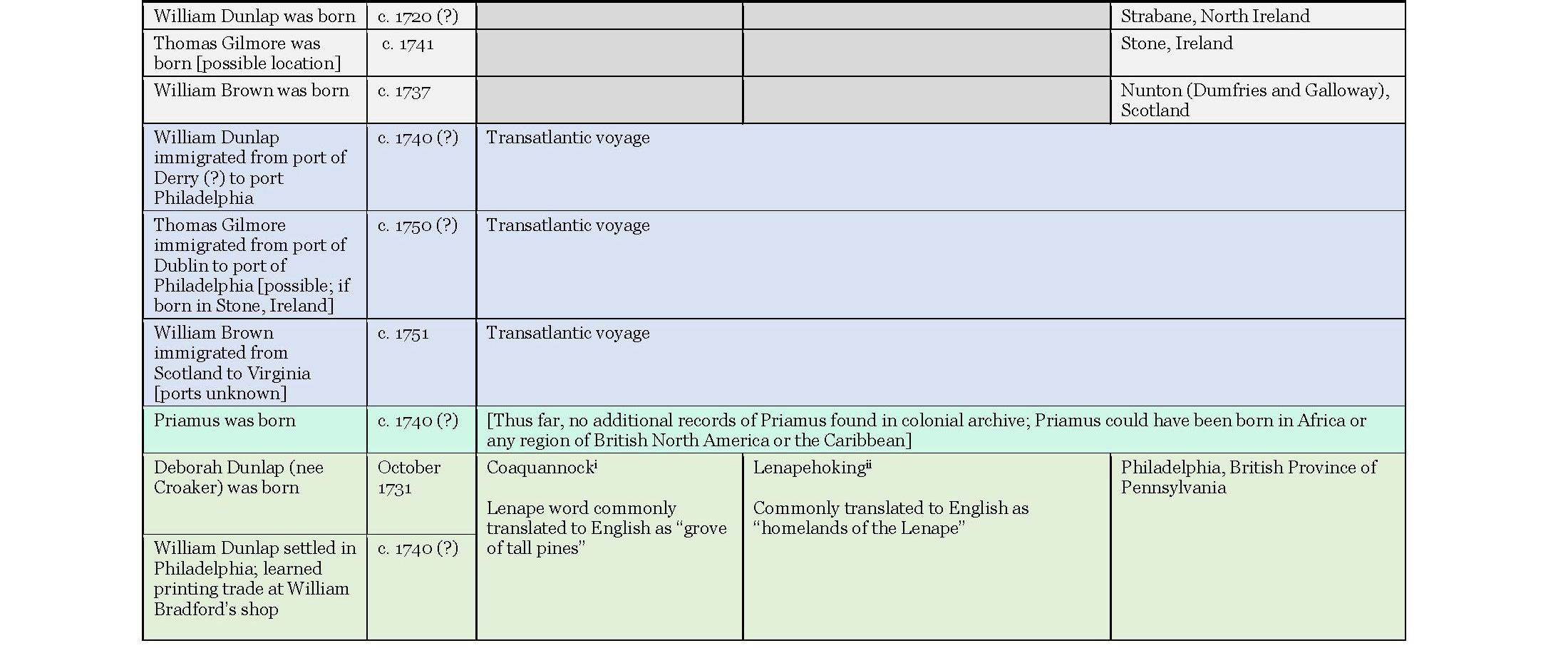

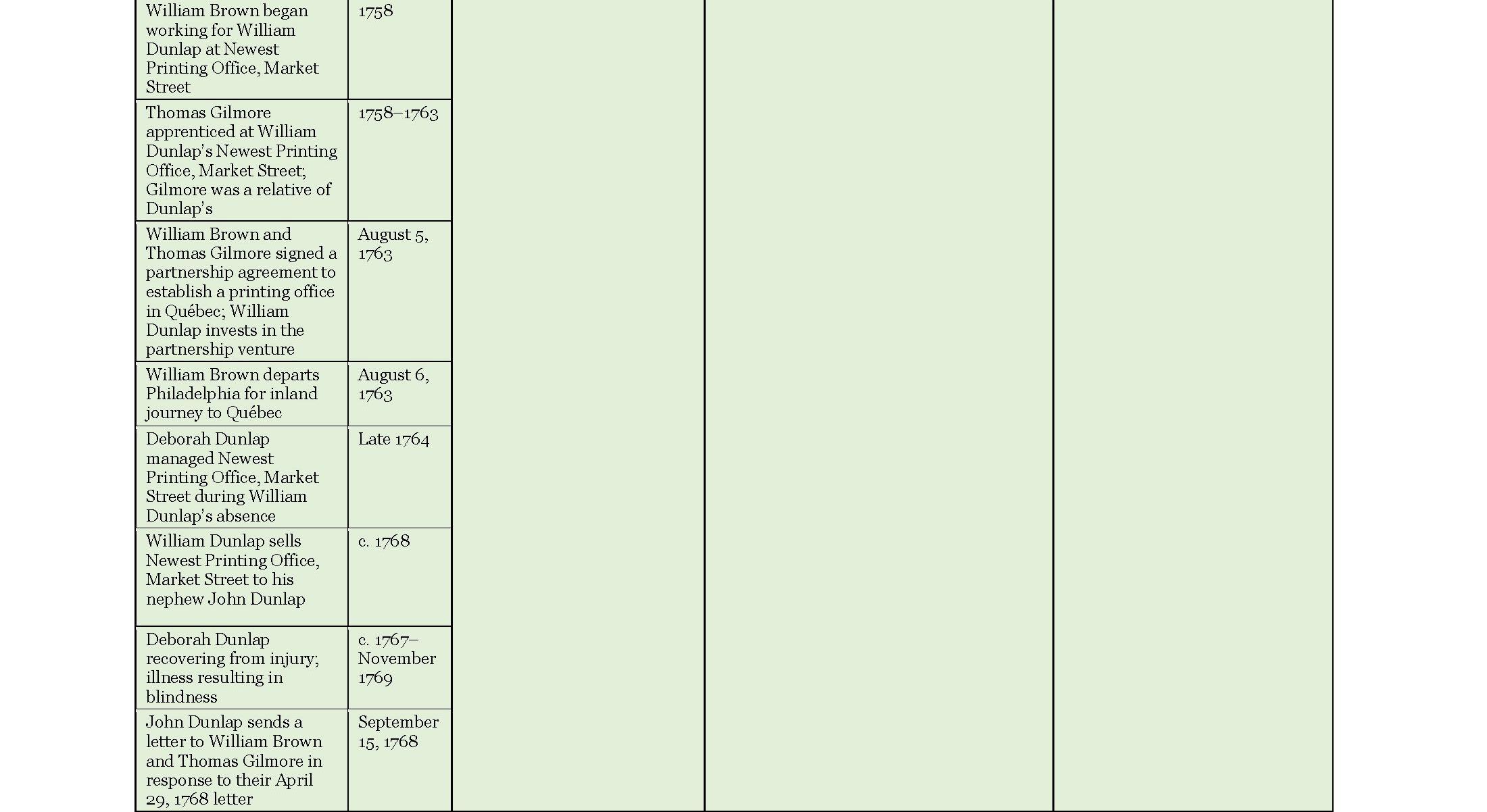

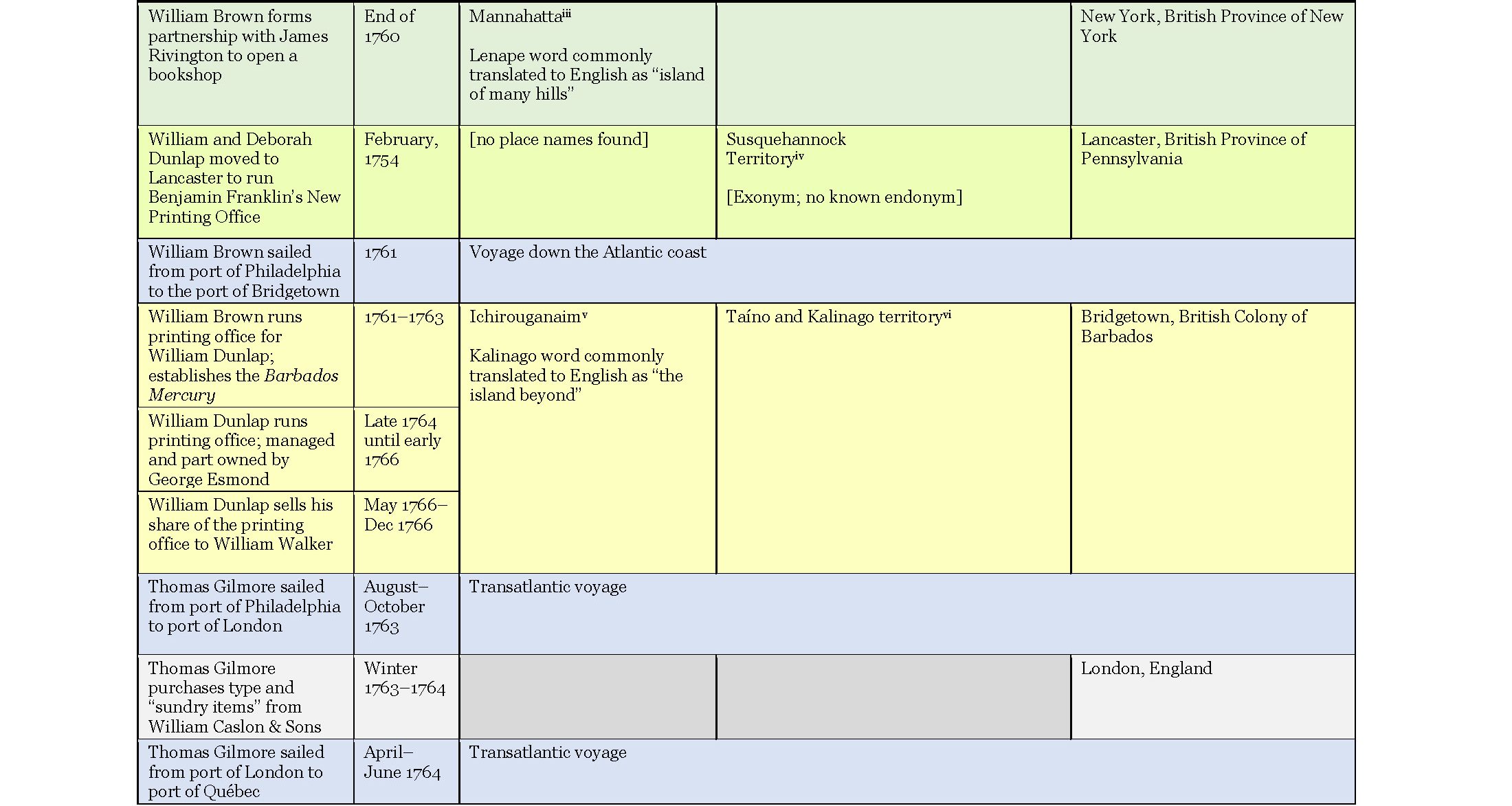

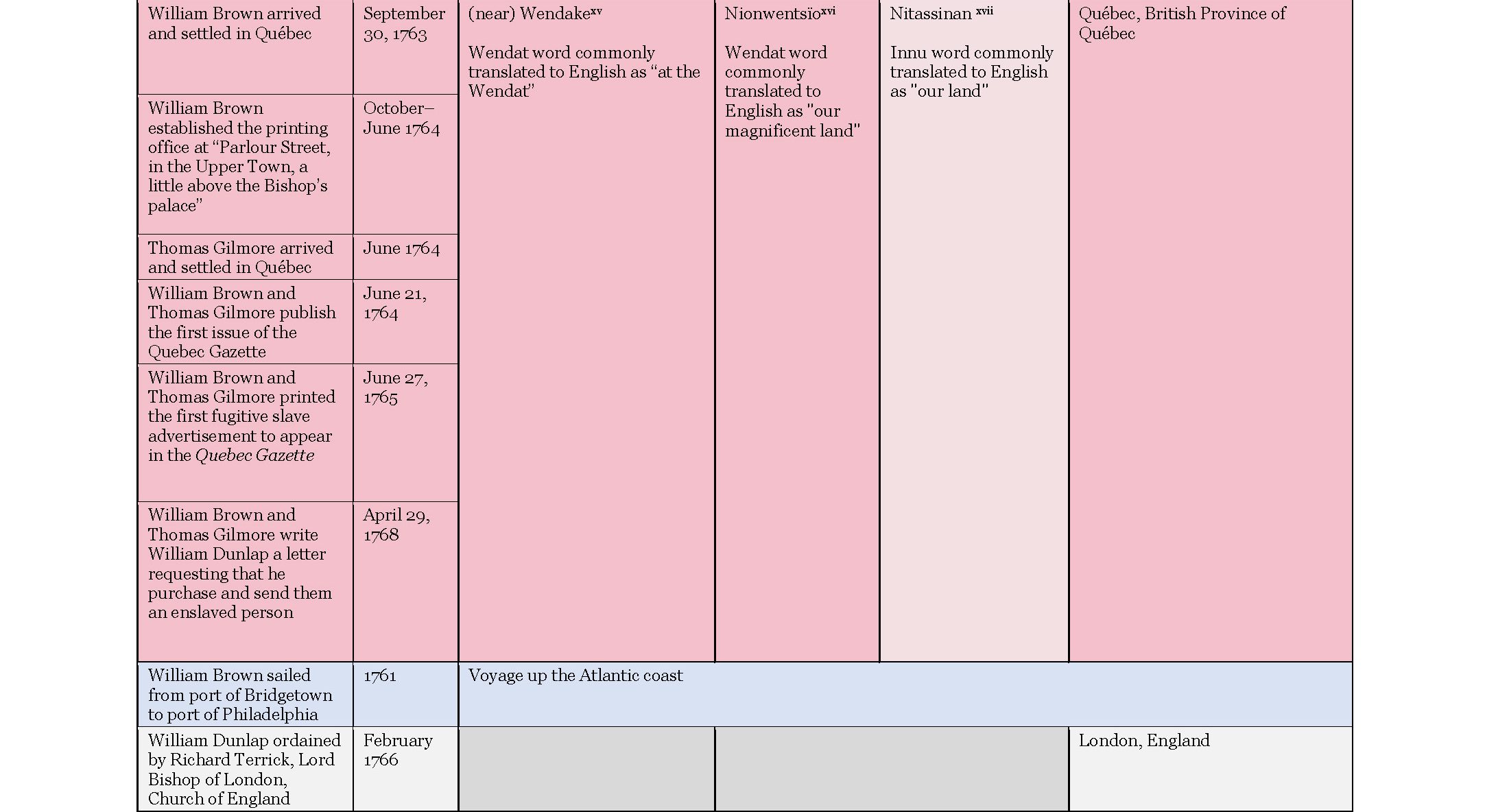

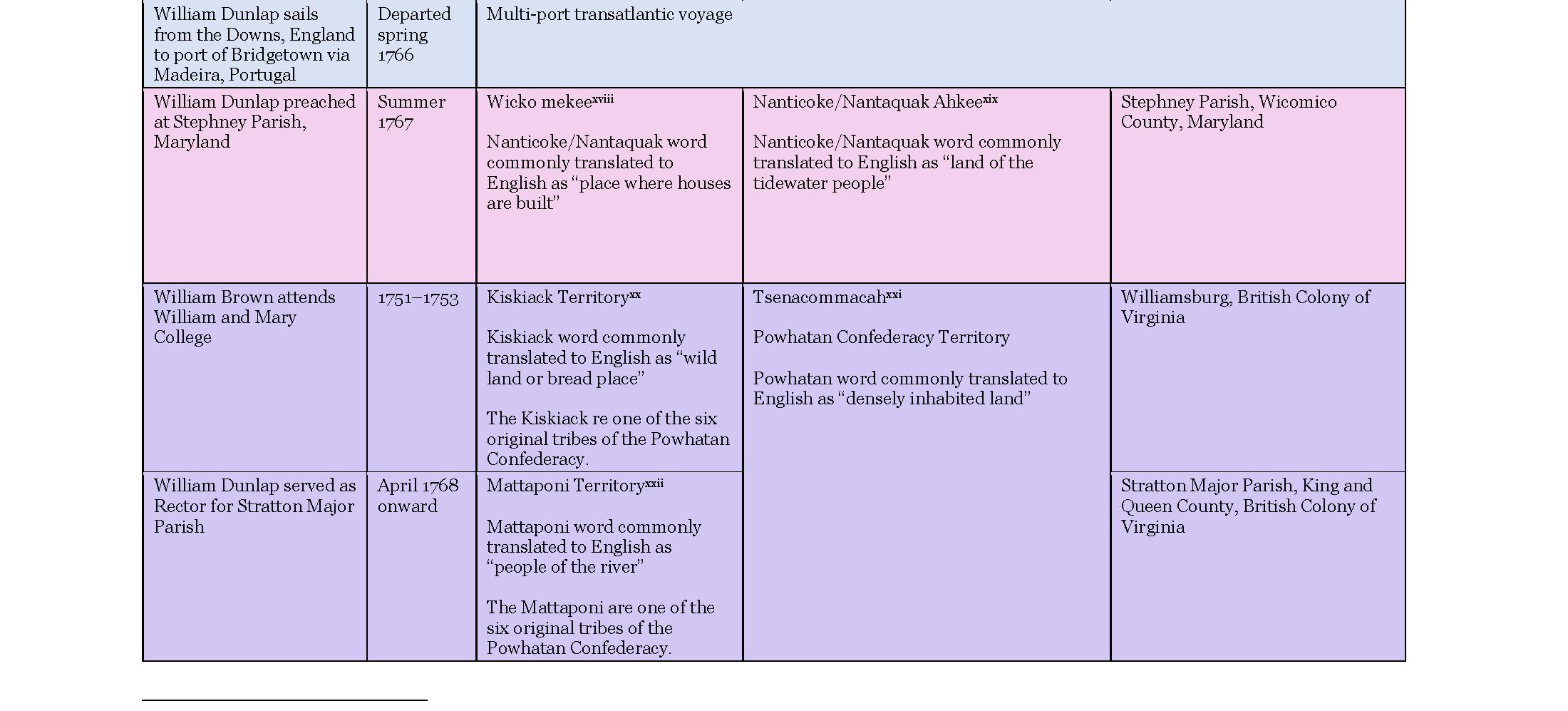

I propose that Brown and Gilmore’s April 1768 correspondence can be more fully understood if the biographical history of the key players in the letter are traced with a method that recognizes the sovereign Indigenous territories upon which the colonial settlements and borders were violently imposed. For the purposes of this case study, I provide a table (Appendix 1) of territories networked to Brown and Gilmore’s April 1768 letter through the biographical highlights of the key five individuals mentioned in the letter up to the time of its writing. At a high-level, the network of territories reveals an integrated relationship of slavery and empire in both northern temperate regions and tropical and semi-tropical southern regions—and movement between these regions. Nelson’s conceptualization of a “second Middle Passage between the shores of the Caribbean and Canada”[86] is central to understanding this connectivity. She argues that examining colony-to-colony trade reveals understudied North/South Atlantic routes previously excluded from the dominant definition of “triangular trade,” contributing to the erasure of slavery in Canada and the American North.[87] Analysis of the territorial network of Brown and Gilmore’s April 1768 letter reveals that Brown, Gilmore, and Dunlap traveled between Philadelphia/settler-occupied Coaquannock, Québec/settler-occupied Nionwentsïo Bridgetown/settler-occuped Ichirouganaim, and Williamsburg/settler-occupied Kiskiack Territory—to name a few.

Brown and Gilmore’s April 1768 letter is also networked to territorial contestation between two European empires that involved both Indigenous/settler alliances and conflicts, and Indigenous resistance. For example, Indigenous resistance to colonial land disposition in Susquehannock Territory[88]/western Pennsylvania surfaces in the (colonial) biographies of William Dunlap and Deborah Dunlap, where historian Mary Turnbull writes, “possibly because of Indian attacks in western Pennsylvania, which followed Braddock’s defeat, Deborah Dunlap returned to the Franklin home in Philadelphia.”[89] Indeed, during the time-period networked to this document (1730s-1768) colonial borders were in flux[90] as colonial land dispossession of Indigenous territories rolled out unevenly. Differing temporal nature of territories needs additional contemplation in future development for Territory Network Methodology—how can continuous Indigenous territorial stewardship be compared to (temporary) colonial territorial control?

Extensive study outside the scope of this paper is required to estimate and analyze how Brown and Gilmore’s movements through territories and interaction with broader systems and processes such as of treaty relations, war and contestation of territory were formative to their direct participation Transatlantic Slavery as enslavers. Additionally, as I continue to develop Territorial Network Methodology, I want to explore how interactive and digital mapping tools can visualize the complexities of the territories networked Brown and Gilmore’s April 1768 letter. The capacity of writing and data tables to attend concisely to the complexities of overlapping/contested/co-existent/imposed/continuous territories is limited. I am hopeful that interactive and visual means can more holistically communicate connections between Transatlantic slavery and settler colonialism in the territories that became Canada.

Bibliography

“A list of settlers victual’d at this place [Halifax] between the eighteenth day of May & fourth day of June 1750…” Nova Scotia Archives. Accessed January 14, 2024. https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/archives/?ID=3.

“African Nova Scotians in the Age of Slavery and Abolition: Slavery and Freedom, 1749–1782.” Nova Scotia Archives. Accessed January 14, 2024. https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/results/?Search=&SearchList1=1.

“An Ancestral Culture, a Fascinating History.” Tourisme Wendake. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://tourismewendake.ca/en/informations/about/.

“Brief History.” Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.mohican.com/brief-history/.

“Carte du Nionwentsïo.” Nation Huronne-Wendat. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://wendake.ca/cnhw/bureau-du-nionwentsio/a-propos/carte-du-nionwentsio/.

“Mandate Areas: Canadian Slavery.” Slavery North. Accessed January 14, 2024. https://slaverynorth.com/mandate-areas/.

“Lenapehoking is the Homeland of the Lenape.” Lenape Center. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://lenape.center/.

“Life on the River.” Wicomico River Stewardship Initiative. Accessed June 17, 2023. http://www.wicomicoriver.org/life-on-the-river.html

“Our History.” The Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://massachusetttribe.org/our-history.

“Philadelphia Region When Known as Coaquannock map.” Map. Philadelphia City Planning Commission. Width: 62.5 cm, Height: 86.5 cm. 1934. Historical Society of Pennsylvania map collection.

“Sir David Kirke.” In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published September 18, 2008; last edited January 17, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sir-david-kirke.

“Virginia-Pennsylvania Boundar.” Virginia Places. Accessed January 14, 2024. http://www.virginiaplaces.org/boundaries/paboundary.html.

“We Are The Massachusett.” The Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://massachusetttribe.org/we-are-the-massachusett.

“Welcome to the Kiskiack Chickahominy Tribe.” The Kiskiack Chickahominy Tribe. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://thekiskiackchickahominytribe.com/.

Ashini, Jolene and Chelsee Arbour. “Our Land: Mapping Nitassinan.” Artic Arts Summit. June 16, 2022. https://arcticartssummit.ca/articles/our-land-mapping-nitassinan/.

Beckles, Hilary McD. “Kalinago (Carib) Resistance to European Colonisation of the Caribbean.” Caribbean Quarterly 38, no. 2/3 (1992): 1–14, 123–124.

Brown, William and Thomas Gilmore to William Dunlap. Letter. April 29, 1768. Neilson Collection, MG 24, B1 Volume 47, file 2: Brown & Gilmore record – correspondence of William Brown & William Dunlap, 1763-1771 (pages 1–23, 25–29). Microfilm C-15778, Library and Archives Canada.

Brown, Willis L. “A Likely Negro and Without Fault.” Negro History Bulletin 18, no. 8 (1955): 177–79.

Campbell, R. “Of Letter Printing and Printers.” In The London Tradesman: Being an Historical Account of all the Trades, Professions, Arts, Both Liberal and Mechanic, 120–123. London: T. Gardener, 1747.

Colonial Williamsburg. Live from the Printshop. YouTube. July 17, 2020. Video, 36:09. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DhQf2VJ7Itw.

Davidson, Emily. “Ink Stained: Experiments Towards Decolonizing Print.” Master of Fine Arts thesis, NSCAD University, 2023.

Davidson, Emily. “PUBLIC 64 Territory Network.” PUBLIC: beyond unsettling: methodologies for decolonizing futures. Guest editors Leah Dector and Carla Taunton. 32, no. 64 (Fall 2021): 136–19.

Decolonial Atlas. Turtle Island Decolonized: Indigenous Names of Major Cities and Historical Sites. Map. Version 1.0, 2023. “Turtle Island Decolonized: Mapping Indigenous Names across ‘North America.’” The Decolonial Atlas. Accessed November 8, 2023, https://decolonialatlas.wordpress.com/turtle-island-decolonized/

Delaronde, Karonhí:io and Jordan Engel. “Kanonshionni’onwè:ke tsi ionhwéntsare (Haudenosaunee Country) in Kanien’kéha (Mohawk).” Map. The Decolonial Atlas. February 4, 2015. https://decolonialatlas.wordpress.com/2015/02/04/haudenosaunee-country-in-mohawk-2/.

Dunlap, John to William Brown and Thomas Gilmore. Letter. September 15, 1768. Brown and Gilmore, printers: C-15778, MG 24 B 1. Library and Archives Canada. https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c15778/641.

Dunlap, William to William Brown and Thomas Gilmore. Letter. 1768. Brown and Gilmore, printers: C-15778, MG 24 B 1. Library and Archives Canada. https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c15778/657.

Dunlap, William to William Brown and Thomas Gilmore. Letter. February 28, 1768. Brown and Gilmore, printers: C-15778, MG 24 B 1. Library and Archives Canada. https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c15778/649.

Dunlap, William to William Brown and Thomas Gilmore. Letter. July 7, 1767. Brown and Gilmore, printers: C-15778, MG 24 B 1. Library and Archives Canada. https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c15778/646.

Dunlap, William to Benjamin Franklin. Letter. February 1, 1766. National Archives, Founders Online. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-13-02-0025.

Franklin, Benjamin to Deborah Franklin. Letter. June 10, 1758. National Archives, Founders Online. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-08-02-0017.

Gervais, Jean-Francis. “GILMORE, THOMAS.” In Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–. Accessed June 16, 2023. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gilmore_thomas_4E.html.

Gervais, Jean-Francis, in collaboration with. “BROWN, WILLIAM.” In Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–. Accessed June 16, 2023. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brown_william_4E.html.

Gespe’gewa’gi Mi’gmawei Mawiomi. “Our Place Names.” In Nta’tugwaqanminen: Our Story, Evolution of the Gespe’gewa’gi Mi’gmaq. 24–48. Halifax & Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2016.

James N. Green and Brown University students. “Abolition.” Brazil: Five Centuries of Change. Companion website to James N. Green and Thomas E. Skidmore. Brazil: Five Centuries of Change. 3rd edition. London: Oxford University Press, 2021. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://library.brown.edu/create/fivecenturiesofchange/chapters/chapter-4/abolition/.

Greenwood, Emma L. “Work, Identity and Letterpress Printers in Britain, 1750–1850.” PhD Arts, Languages and Cultures, University of Manchester, 2015.

Hall, Anthony J. “Royal Proclamation of 1763.” In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published February 07, 2006. Last Edited August 30, 2019. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/royal-proclamation-of-1763.

Henry-Dixon, Natasha. “Black Enslavement in Canada,” In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published June 13, 2016; last edited February 09, 2022. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement

Henry-Dixon, Natasha. “Slavery Abolition Act, 1833.” In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published July 10, 2014; last edited November 05, 2021. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement.

Hoiser, E. “‘I have the honor to be, your obedient servant’: Why Did Washington End His Letters this Way?” Lives and Legacies (blog). September 17, 2020. https://livesandlegaciesblog.org/2020/09/17/i-have-the-honor-to-be-your-obedient-servant-why-did-washington-end-his-letters-this-way/.

Honeychurch, Lennox. “They Called it Ichirou-gà-naim: The Island Beyond.” The Ins and Outs of Barbados 34 (2017): unpaginated.

Hyde, George E. “Pawnee Origins.” In The Pawnee Indians. 2nd edition. Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1974.

Jarzombek, Mark. “The ‘Indianized’ Landscape of Massachusetts.” Places Journal. February 2021. https://doi.org/10.22269/210209

Lawrence, Bonita. “Enslavement of Indigenous People in Canada.” In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published November 22, 2016; last edited May 08, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/slavery-of-indigenous-people-in-canada.

Laws, Mike. “Why We Capitalize ‘Black’ (and not ‘white’).” Columbia Journalism Review. June 16, 2020. https://www.cjr.org/analysis/capital-b-black-styleguide.php.

Leech, Marian (Molly). “Place-Names as Monuments: The Entangled Histories of Coaquannock and Philadelphia.” Monument Lab (blog). October 4, 2022. https://monumentlab.com/bulletin/place-names-as-monuments-the-entangled-histories-of-coaquannock-and-philadelphia#note-2.

Lunney, Linde. “Dunlap, John.” In Dictionary of Irish Biography. Published October 2009, last revised October 2009. https://www.dib.ie/biography/dunlap-john-a2848.

Native Land Digital. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://native-land.ca/.

Nelson, Charmaine A. “A ‘Tone of Voice Peculiar to New-England’: Fugitive Slave Advertisements and the Heterogeneity of Enslaved People of African Descent in Eighteenth-Century Quebec.” Current Anthropology 61, no. S22 (October 1, 2020): S303–S316.

Nelson, Charmaine A. “Canadian Fugitive Slave Advertisements: An Untapped Archive of Resistance.” Borealia: Early Canadian History (blog). February 29, 2016. https://earlycanadianhistory.ca/2016/02/29/canadian-fugitive-slave-advertisements-an-untapped-archive-of-resistance/.

Nelson, Charmaine A. “Introduction.” In Slavery, Geography and Empire in Nineteenth-Century

Marine Landscapes of Montreal and Jamaica (London and New York: Routledge, 2016).

Neilson, Colonel Hubert. “Slavery in Old Canada: Before and After the Conquest.” Transactions of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec. Sessions of 1905, no. 26, (1906).

Neilson, J. L. Hubert. “The Origin of Printing on the Shores of the St. Lawrence.” In A Souvenir, the Thousand Islands of the St. Lawrence, 335–347. Edited by John A. Haddock. Alexandria Bay, NY: JNO. A. Haddock, 1895.

Maynard, Robyn and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. “On Letter Writing, Commune, and the End of (This) World.” In Rehearsals for Living. Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022.

Minderhout, David Jay and Andrea T. Frantz. Invisible Indians: Native Americans in Pennsylvania. Amherst, New York: Cambria Press, 2008.

Palmater, Pamela. “My Tribe, My Heirs and Their Heirs Forever: Living Mi’kmaw Treaty.” In Living Treaties: Narrating Mi’kmaw Treaty Relations. Edited by Marie Battiste. Cape Breton: Cape Breton University Press, 2016.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books, 1999.

Schreiber, Michael. “Philadelphia’s Rich Maritime History.” Philahistory.org (blog). August 19, 2019. https://philahistory.org/2019/08/29/philadelphias-rich-maritime-history/.

Ta’n Weji-sqalia’tiek: Mi’kmaw Place Names Digital Atlas and Website Project. Accessed June 16, 2023. https://placenames.mapdev.ca/.

Taylor, Jordan E. “Enquire of the Printer: Newspaper Advertising and the Moral Economy of the North American Slave Trade, 1704–1807.” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 18, no. 3 (2020): 287–323.

Tuck, Eve, Allison Guess and Hannah Sultan. “Not Nowhere: Collaborating on Selfsame Land.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society. June 26, 2014. https://decolonization.wordpress.com/2014/06/26/not-nowhere-collaborating-on-selfsame-land/.

Turnbull, Mary D. “William Dunlap, Colonial Printer, Journalist, and Minister.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 103, no. 2 (1979): 143–65.

Véras, Bruno R. “The Canadian Press on ‘Quant a ce qui concerne Bahia’: White Fear, Diplomacy, Abolitionism, and the News Coverage of the Muslim African Slave Rebellions.” Presentation at the Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery, NSCAD University, Halifax, NS. December 2, 2021. https://youtu.be/AjZECuBklLQ?si=NyepIUnP9hFYGvRK.

Vettikkal, Ann. “The Lenape of Manahatta: A Struggle for Acknowledgement.” The Eye. September 6, 2022. https://www.columbiaspectator.com/the-eye/2022/09/06/the-lenape-of-manahatta-a-struggle-for-acknowledgement/.

Waldstreicher, David. “Reading the Runaways: Self-Fashioning, Print Culture, and Confidence in Slavery in the Eighteenth-Century Mid-Atlantic.” William and Mary Quarterly 56, no. 2 (April 1999): 243–72.

Walvin, James. Black Ivory: A History of British Slavery. Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1995.

Whitt, Laurelyn, and Alan W. Clarke. “The Powhatan Tsenacommacah (1607–1677).” In North American Genocides: Indigenous Nations, Settler Colonialism, and International Law, 117–61. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Appendix 1. Territory Network Data for Biographical Highlights of William Brown, Thomas Gilmore, William Dunlop, Deborah Dunlap, and Priamus (1720-1768)

Appendix 1 Endnotes

Appendix 1 Endnotes

i “Philadelphia Region When Known as Coaquannock map,” map, Philadelphia City Planning Commission, width: 62.5 cm, height: 86.5 cm, 1934, Historical

Society of Pennsylvania map collection and Leech, “Place-Names as Monuments.”

ii “Lenapehoking is the homeland of the Lenape,” Lenape Center, accessed July 17, 2023, https://lenape.center/

iii Ann Vettikkal, “The Lenape of Manahatta: A Struggle for Acknowledgement,” The Eye, September 6, 2022, https://www.columbiaspectator.com/theeye/

2022/09/06/the-lenape-of-manahatta-a-struggle-for-acknowledgement/

iv David Jay Minderhout and Andrea T. Frantz, Invisible Indians: Native Americans in Pennsylvania, (Amherst, New York: Cambria Press, 2008), 53.

v Lennox Honeychurch, “They Called it Ichirou-gà-naim: The Island Beyond,” The Ins and Outs of Barbados 34 (2017): unpaginated.

vi Hilary McD. Beckles, “Kalinago (Carib) Resistance to European Colonisation of the Caribbean,” Caribbean Quarterly, 38, no. 2/3 (1992): 1.

vii “We Are The Massachusett,” The Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag, accessed June 17, 2023, https://massachusetttribe.org/we-are-the-massachusett “Our

History,” The Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag, accessed June 17, 2023, https://massachusetttribe.org/our-history

viii Mark Jarzombek, “The “Indianized” Landscape of Massachusetts,” Places Journal, February 2021.

ix Karonhí:io Delaronde and Jordan Engel, “Kanonshionni’onwè:ke tsi ionhwéntsare (Haudenosaunee Country) in Kanien’kéha (Mohawk),” map, Decolonial

Atlas, February 4, 2015, https://decolonialatlas.wordpress.com/2015/02/04/haudenosaunee-country-in-mohawk-2/

x Delaronde and Engel, “Kanonshionni’onwè:ke tsi ionhwéntsare.”

xi “Brief History,” Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians, Accessed July 17, 2023, https://www.mohican.com/brief-history/

xii Delaronde and Engel, “Kanonshionni’onwè:ke tsi ionhwéntsare.”

xiii Delaronde and Engel, “Kanonshionni’onwè:ke tsi ionhwéntsare.”

xiv Delaronde and Engel, “Kanonshionni’onwè:ke tsi ionhwéntsare.”

xv “An Ancestral Culture, a Fascinating History,” Tourisme Wendake, accessed June 17, 2023, https://tourismewendake.ca/en/informations/about/

xvi “Carte du Nionwentsïo,” Nation Huronne-Wendat, accessed June 17, 2023, https://wendake.ca/cnhw/bureau-du-nionwentsio/a-propos/carte-du-nionwentsio/

xvii Jolene Ashini and Chelsee Arbour, “Our Land: Mapping Nitassinan,” Artic Arts Summit, June 16, 2022,

https://arcticartssummit.ca/articles/our-land-mapping-nitassinan/

xviii “Life on the River,” Wicomico River Stewardship Initiative, accessed June 17, 2023, http://www.wicomicoriver.org/life-on-the-river.html

xix “History,” The Nanticoke Indian Tribe, accessed June 17, 2023, https://www.nanticokeindians.org/page/history

xx “Welcome to the Kiskiack Chickahominy Tribe,” The Kiskiack Chickahominy Tribe, accessed June 17, 2023, https://thekiskiackchickahominytribe.com/

xxi Laurelyn Whitt and Alan W. Clarke, “The Powhatan Tsenacommacah (1607–1677),” in North American Genocides: Indigenous Nations, Settler Colonialism,

and International Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019): 117.

xxii “We are the Mattaponi Tribe,” The Official Site of the Mattaponi Indian Reserve Tribe, accessed June 17, 2023, https://www.mattaponination.com/

Appendix 2. Transcription of William Brown and Thomas Gilmore to William Dunlap, Letter, April 29, 1768

Quebec, April 29th, 1768

Rev. Sir,

Yours of the 28th of February last we received in due Time. We heartily condole with you on W. Dunlap’s unhappy Situation, and are anxious to hear of her Recovery, which we most earnestly wish for. We are glad to find you have disposed of the Bill, whereupon we have balanced your Accompt in our Books, aggregable to the Accompt transmitted you last May, which you allow to be by rights, and say “you have copied it exactly into your Books,” in your Letter of Octr. 26th, of 1767 which inclosed the seal Signatures of our Bonds. The Exchange on the Bill we have reckoned of Part being entirely ignorant what it was in Philadelphia at the Time you disposed of it. Yours inclosing the Signatures of our Bonds, did not inform us of the Disposal of the Bill, but quite the contrary; nor did it contain a Copy of our Accompt with you as mentioned in your last. On settling your Acct. we find is a Balance in our Favour of one Guinea which, together with the £12u18u0 Your Currency, out of which we beg you may in the first Place discharge William Brown’s private Acct. of £4u12u10, and next, whatever Balance may remain due to you on Thomas Gilmore’s private Acct. (which he desires you may send him an Acct. of) and if any Balance remains carry it to the Credit of our New Acct. We expect you will send us Discharges in full of all Accts. and if not omit informing us if Gaine has paid, and we shall credit him and charge you for that Sum; if he has not yet paid, and you should not chuse to take it upon yourself it would be high Time for us to fall on some Method of getting paid. You’ll Please take Notice that Gaine’s Acct. was not charged the State of Acct. betwixt you and us sent you.

Having been long embarrassed with Canadian Boys as menial Servants about The Printing Office a who will not engage for any considerable Time and as soon as they find themselves useful augment their Wages and become intolerable insolent, we are at last come to a Resolution of trying to get a Negro Boy, wherefore we beg you will endeavor to purchase one for us, if to be had in your City, Country between 15 and 20 Years of Age, fit to put to Press, and who has had the Small Pox, and is Country born, and can be recommended for his Honesty; we would not begrudge you a pretty good Price for such a likely Negro: or if you should be inclinable to part with your Boy Praimus, we would be glad to have him, and would be willing to give what might be judged a reasonable Price. We pray you may try to procure us one so as to have him in the fall, and as soon as you shall be certain of him, or determined to with your own we beg you may loose no Time in acquainting us of the Price, which we will immediately remit you in a Bill on York, as we shall have the Cash ready till we hear from you. Should it be too late for an Opportunity from Philadelphia, there has always been Vessels from York in August and Sept. and we doubt not but there will be this year. We shall expect the Stove by the first Opportunity from your Port. We are, with profound Respect, Sir, your most obliged humbled servants

Brown & Gilmore

An exact Copy sent the aforesaid Date

NB The Balance of W Brown’s Acct. was in your Favour when he left Philadelphia } £6u8u8

The Interest on your Bond to him from June 23 till Nov. 25 £1u15u10/4u12u10

P.S. If you are so lucky as to get a Negro, before you embark him, we beg he may be insured.

Copy of Letter to Wm. Dunlap, 29th April 1768

Appendix 3. William Brown and Thomas Gilmore to William Dunlap,

Letter, April 29, 1768

Neilson Collection, MG 24, B1 Volume 47, file 2: Brown & Gilmore record – correspondence of William Brown & William Dunlap, 1763–1771 (pages 1–23, 25–29). Microfilm C-15778, Library and Archives Canada.

- For coverage on slavery studies and the absence of Canadian Slavery studies within the discourse, see Charmaine A. Nelson, “Introduction,” in Slavery, Geography and Empire in Nineteenth-Century Marine Landscapes of Montreal and Jamaica (London and New York: Routledge, 2016), 2–8. ↵

- William Brown and Thomas Gilmore to William Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768, Neilson Collection, MG 24, B1 Volume 47, file 2: Brown & Gilmore record - correspondence of William Brown & William Dunlap, 1763–1771 (pages 1–23, 25–29) Microfilm C-15778, Library and Archives Canada. Thank you to Dr. Charmaine A. Nelson for providing me with this source. ↵

- Throughout this essay I capitalize Black, and not white, when referring to people or groups in racial, ethnic, or cultural terms. I follow Black journalist and editor Alexandria Neason’s rationale, that to capitalize Black “is to acknowledge that slavery ‘deliberately stripped’ people forcibly shipped overseas ‘of all other ethnic/national ties.’” Mike Laws, “Why We Capitalize ‘Black’ (and not ‘white’),” Columbia Journalism Review, June 16, 2020, https://www.cjr.org/analysis/capital-b-black-styleguide.php. ↵

- “Mandate Areas: Canadian Slavery,” Slavery North, accessed January 14, 2024, https://slaverynorth.com/mandate-areas/. See also: Natasha Henry-Dixon, “Black Enslavement in Canada,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, article published June 13, 2016; last edited February 09, 2022, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement and Bonita Lawrence, “Enslavement of Indigenous People in Canada,” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada, article published November 22, 2016; last edited May 08, 2020, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/slavery-of-indigenous-people-in-canada ↵

- Nelson, “Introduction,” 3. ↵

- Henry-Dixon, “Black Enslavement in Canada,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement ↵

- “Sir David Kirke,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, article published September 18, 2008; last edited January 17, 2020, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sir-david-kirke. ↵

- Henry-Dixon, “Black Enslavement in Canada,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement ↵

- The term “panis” was used in New France to describe an enslaved person from any Indigenous group in North America. White settler anthropologist George E. Hyde describes how the derivation of the term relates to the Pawnee Nation, “In the middle of the 17th century the Pawnees were being savagely raided…The raiders carried off such great numbers of Pawnees into slavery that in the country on and east of the upper Mississippi the name Pani developed a new meaning: slave. The French adopted this meaning, and Indian slaves, no matter from which tribe they had been taken, were presently being termed Panis.” George E. Hyde, “Pawnee Origins,” in The Pawnee Indians, 2nd ed. (Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1974), 24. See also: Lawrence, “Enslavement of Indigenous People in Canada,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/slavery-of-indigenous-people-in-canada and Henry-Dixon, “Black Enslavement in Canada,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement. ↵

- Henry-Dixon, “Black Enslavement in Canada,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement ↵

- Henry-Dixon, “Black Enslavement in Canada,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement ↵

- Article XLVII, Articles of Capitulation, Montreal, September 8, 1760, quoted by Henry-Dixon, “Black Enslavement in Canada,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement. In the Articles of Capitulation “Roman Religion” refers to Roman Catholicism. ↵

- Anthony J. Hall, “Royal Proclamation of 1763,” in The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, article published February 07, 2006, last edited August 30, 2019, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/royal-proclamation-of-1763. ↵

- “African Nova Scotians in the Age of Slavery and Abolition: Slavery and Freedom, 1749–1782,” Nova Scotia Archives, accessed January 14, 2024, https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/results/?Search=&SearchList1=1. ↵

- “A list of settlers victual’d at this place [Halifax] between the eighteenth day of May & fourth day of June 1750...,” Nova Scotia Archives, accessed January 14, 2024, https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/archives/?ID=3 ↵

- Henry-Dixon, “Black Enslavement in Canada,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement. ↵

- This statute is also known as the Slavery Abolition Act. ↵

- Natasha Henry-Dixon, “Slavery Abolition Act, 1833,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, article published July 10, 2014; last edited November 05, 2021, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/slavery-abolition-act-1833. ↵

- Natasha Henry-Dixon, “Slavery Abolition Act, 1833,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/slavery-abolition-act-1833. ↵

- Henry-Dixon, “Black Enslavement in Canada,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement. ↵

- Bruno R. Véras, “The Canadian Press on ‘Quant a ce qui concerne Bahia’: White Fear, Diplomacy, Abolitionism, and the News Coverage of the Muslim African Slave Rebellions,” presentation, Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery, NSCAD University, Halifax, NS, December 2, 2021, https://youtu.be/AjZECuBklLQ?si=NyepIUnP9hFYGvRK. See also: James Walvin, Black Ivory: A History of British Slavery, (Washington, DC, Howard University Press, 1995), 310. ↵

- James N. Green and Brown University students, “Abolition,” Brazil: Five Centuries of Change, companion website to James N. Green and Thomas E. Skidmore, Brazil: Five Centuries of Change, 3rd ed. (London, Oxford University Press, 2021). https://library.brown.edu/create/fivecenturiesofchange/chapters/chapter-4/abolition/. ↵

- The majority of the section “Territory Network Methodology” appeared first in Emily Davidson, “Ink Stained: Experiments Towards Decolonizing Print” (Master of Fine Arts thesis, NSCAD University, 2023), 22–26. ↵

- For discussion on the possibilities and limitations of land acknowledgments, see: Dylan Robinson, Kanonhsyonne Janice C. Hill, Armand Garnet Ruffo, Selena Couture, and Lisa Cooke Ravensbergen, “Rethinking the Practice and Performance of Indigenous Land Acknowledgement,” Canadian Theatre Review 177, no. 1 (2019): 20–30. ↵

- A few examples of Indigenous-led mapping projects are: Ta'n Weji-sqalia'tiek: Mi'kmaw Place Names Digital Atlas and Website Project, accessed June 16, 2023, https://placenames.mapdev.ca/; “Carte du Nionwentsïo,” Nation Huronne-Wendat, accessed June 17, 2023, https://wendake.ca/cnhw/bureau-du-nionwentsio/a-propos/carte-du-nionwentsio/; Jolene Ashini and Chelsee Arbour, “Our Land: Mapping Nitassinan,” Artic Arts Summit, June 16, 2022, https://arcticartssummit.ca/articles/our-land-mapping-nitassinan/. ↵

- Two examples of intercultural collaborations that focus on Indigenous place names and territories are: Native Land Digital, accessed June 17, 2023, https://native-land.ca/ and Decolonial Atlas, Turtle Island Decolonized: Indigenous Names of Major Cities and Historical Sites, map, version 1.0, 2023, “Turtle Island Decolonized: Mapping Indigenous Names across ‘North America,’” Decolonial Atlas, accessed November 8, 2023, https://decolonialatlas.wordpress.com/turtle-island-decolonized/ ↵

- Linda Tuhiwai Smith, “Twenty-five Indigenous Projects,” in Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, second ed., (London, Zed Books, 2012), 262. ↵

- Smith, “Twenty-five Indigenous Projects,” 262. ↵

- Examples of such sources are First Nation websites, Indigenous-authored scholarly articles and books, and Indigenous-led mapping projects. ↵

- The Gespe’gewa’gi Mi’mgawei Mawiomi describe how the process of cultural and linguistic borrowing is expressed in Mi’gmaw naming practices, stating “when a reality of one cultural group does not exist in the other group’s culture, the word expressing that reality is borrowed by the second group.” Gespe'gewa'gi Mi'gmawei Mawiomi, “Our Place Names,” in Nta'tugwaqanminen: Our Story, Evolution of the Gespe'gewa'gi Mi'gmaq (Halifax & Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2016), 28. ↵

- Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 9. ↵

- One example of an Indigenous place naming practice is described by the Gespe'gewa'gi Mi'mgawei Mawiomi, who write, “Mi'gmaq place names, as with most ancient place names, are based on descriptive words. They describe features of the landscape, and to a lesser extent, how oral history is woven into the specific places in the landscape. In this way, when people discuss their travels and the routes they followed, at the same time they draw a portrait of the landscape and what happened there. This allows travellers to “recognize” the many landmarks of a landscape when they see them for the first time.” Gespe’gewa’gi Mi’gmawei Mawiomi, “Our Place Names,” 28. ↵

- A local trend of using the Mi'kmaw language place name Kjipuktuk (commonly translated to English as “great harbour”) to refer to peninsular Halifax is evidenced in organization naming by both Mi'kmaw-led and settler-majority groups since at least 2019. Kjipuktuk Community College is run by the Mi'kmaw Native Friendship Centre; Mayworks Halifax changed its name Mayworks Kjipuktuk | Halifax in 2020; Solidarity Halifax became Solidarity Kjipuktuk/Halifax in 2019; Nocturne Art at Night added Kjipuktuk/Halifax to its promotional materials in 2019; and a newly-formed white settler solidarity group named itself Allyship Kjipuktuk in 2020. ↵

- The introductory text for Turtle Island Decolonized, states: “some major cities are missing from the map because, as our collaborator DeLesslin George-Warren (Catawba) pointed out, ‘The fact is that we’ve lost so much in terms of our language and place names. It might be more honest to recognize that loss in the map instead of giving the false notion that the place name still exists for us.’” “Turtle Island Decolonized,” Decolonial Atlas, https://decolonialatlas.wordpress.com/turtle-island-decolonized/. ↵

- For an example of Indigenous place name mapping, see: Ta'n Weji-sqalia'tiek: Mi'kmaw Place Names Digital Atlas and Website Project, accessed June 16, 2023, https://placenames.mapdev.ca/. For coverage on settler re-naming of Indigenous places as a process of claiming and possession, see: Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 1999), 81. ↵

- The Mi'kmaw language has multiple orthographies. I have aimed to use the Listuguj orthography when discussing texts by Listuguj authors, such as Gespe’gewa’gi Mi’gmawei Mawiomi. In other instances, I use the Francis-Smith orthography because it is the most common orthography in the part of Mi'kma'ki where I am settled, and is the official orthography of Mi'kmaq Sante' Mawio'mi (Grand Council). ↵

- Gespe’gewa’gi Mi’gmawei Mawiomi, “Our Place Names,” 28. ↵

- Interactive and digital mapping tools may have utility towards visualizing overlapping and contested territories in future iterations of this inquiry. I am grateful to Graham Nickerson for his encouragement and advice to focus my early efforts on the creation of accurate data table, which can later be input into digital mapping software. Graham Nickerson in conversation with the author, October 20, 2023. For an example how territorial network methodology can be visualized, see: Emily Davidson, “PUBLIC 64 Territory Network,” PUBLIC: beyond unsettling: methodologies for decolonizing futures, guest editors Leah Dector and Carla Taunton 32, no. 64 (Fall 2021): 136–19. To view a digital image of the artwork “PUBLIC 64 Territory Network,” see: “PUBLIC 64 Territory Network,” Emily Davidson Art, accessed July 17, 2023, https://emilydavidsonart.com/#jp-carousel-194. ↵

- For an example of Indigenous sovereignty articulated in the terms of “legal and cultural obligation to manage and protect” territory, see: Pamela Palmater, “My Tribe, My Heirs and Their Heirs Forever: Living Mi’kmaw Treaty,” in Living Treaties: Narrating Mi’kmaw Treaty Relations, edited by Marie Battiste, Cape Breton: Cape Breton University Press, 2016: 24. ↵

- For coverage how the process of consciously linking of Indigenous and settler place names can reveal how Indigenous and settler understandings of place are entangled in the same landscape, see: Marian (Molly) Leech, “Place-Names as Monuments: The Entangled Histories of Coaquannock and Philadelphia,” Monument Lab (blog), October 4, 2022. https://monumentlab.com/bulletin/place-names-as-monuments-the-entangled-histories-of-coaquannock-and-philadelphia#note-2. ↵

- The majority of the section “Reading Against the Grain” appeared first in Davidson, “Ink Stained,” 53–55. ↵

- Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 78. See also: Harvey Amani Whitfield, “White Archives, Black Fragments: Problems and Possibilities in Telling the Lives of Enslaved Black People in the Maritimes,” Canadian Historical Review 101, no. 3 (August 2020): 323-345; and Charmaine A. Nelson, “Fugitive Slave Advertisements: As Untapped Archive of Resistance,” Borealia: Early Canadian History, February 29, 2016 https://earlycanadianhistory.ca/2016/02/29/canadian-fugitive-slave-advertisements-an-untapped-archive-of-resistance/. ↵

- Whitfield, “White Archives, Black Fragments,” 326. ↵

- Nelson, “Fugitive Slave Advertisements,” https://earlycanadianhistory.ca/2016/02/29/canadian-fugitive-slave-advertisements-an-untapped-archive-of-resistance/. ↵

- Charmaine A. Nelson, “A ‘Tone of Voice Peculiar to New-England’: Fugitive Slave Advertisements and the Heterogeneity of Enslaved People of African Descent in Eighteenth-Century Quebec,” Current Anthropology 61, no. S22 (October 1, 2020): S310. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore write, “Should it be too late for an Opportunity from Philadelphia, there has always been Vessels from York in August and Sept,” which indicates that they thought Dunlap was in Philadelphia at the time of sending the letter. However, according to Mary D. Turnbull, by April 1768, William Dunlap had already taken up a post as minister of Stratton Major Parish in King and Queen County, Colony of Virginia. Mary D. Turnbull, “William Dunlap, Colonial Printer, Journalist, and Minister,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 103, no. 2 (1979):158. Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- William Brown was born c. 1737 at Nunton (Dumfries and Galloway), Scotland. In collaboration with Jean-Francis Gervais, “BROWN, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed June 16, 2023, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brown_william_4E.html. ↵

- Thomas Gilmore was born 1741 in either Stone, Ireland or Philadelphia, British Province of Pennsylvania. In the case that Gilmore was born in Philadelphia, he was likely a settler of Irish descent. Jean-Francis Gervais, “GILMORE, THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed June 16, 2023, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gilmore_thomas_4E.html. ↵

- I deliberately use the term “occupying” here because of its dual meaning of “inhabitation” and “control by miliary conquest or settlement.” Oxford English Dictionary, 7th ed (2012), s.v. “Occupy.” ↵

- William Dunlap was born in Strabane, North Ireland. Turnbull, “William Dunlap, Colonial Printer, Journalist, and Minister,” 143. ↵

- Hall, “Royal Proclamation of 1763,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/royal-proclamation-of-1763. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. Brown and Gilmore follow the correspondence convention of referring to the wife by the given name of the husband, in this case styled as an initial: “W. Dunlap.” ↵

- Turnbull notes that in 1768 Deborah Dunlap “met with an accident or an illness shortly before the birth of a child which left her blind for the rest of her life.” Turnbull, “William Dunlap, Colonial Printer, Journalist, and Minister,” 157. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- For coverage on work roles in the mid-eighteenth-century printing trade, see: Emma L. Greenwood, “Work, Identity and Letterpress Printers in Britain, 1750–1850,” (PhD Arts, Languages and Cultures, University of Manchester, 2015) and R. Campbell, “Of Letter Printing and Printers,” in The London Tradesman: Being an Historical Account of all the Trades, Professions, Arts, Both Liberal and Mechanic (London: T. Gardener, 1747), 120-123. For differences between guild system in Britain and British North American Colonies, with coverage on role of enslaved people in the colonial printing trade, see: Colonial Williamsburg, Live from the Printshop, YouTube, July 17, 2020, video, 36:09, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DhQf2VJ7Itw. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29 1768. Variations of valedictions where the author refers to themselves as the servant of recipient were common in the eighteenth century, often including expressions of humility and obedience. However, I argue that while not unique to the hierarchies of the printing trade specifically, the deferential valediction reinforces the hierarchy between Dunlop and his former employees. For coverage on the frequency of “servant valediction” and its variations in the eighteenth century, see: E. Hoiser, “‘I have the honor to be, your obedient servant’: Why Did Washington End His Letters this Way?,” Lives and Legacies (blog), September 17, 2020, https://livesandlegaciesblog.org/2020/09/17/i-have-the-honor-to-be-your-obedient-servant-why-did-washington-end-his-letters-this-way/. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. Italics mine. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- Nelson, “A ‘Tone of Voice Peculiar to New-England,’” S310. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29 1768. ↵

- Gervais, “GILMORE, THOMAS.” Gervais, “BROWN, WILLIAM.” See Appendix 1 for additional detail on biographical highlights of Brown, Gilmore, Dunlap, and Priamus. ↵

- Charmaine A. Nelson, “Canadian Fugitive Slave Advertisements: An Untapped Archive of Resistance,” Borealia: Early Canadian History (blog), February 29, 2016. https://earlycanadianhistory.ca/2016/02/29/canadian-fugitive-slave-advertisements-an-untapped-archive-of-resistance/. ↵

- Nelson, “A ‘Tone of Voice Peculiar to New-England,’” S310. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- The brokerage of enslaved people tended to focus on what enslavers considered positive attributes, while fugitive slave advertisements criminalized escapees and rendered them in as much detail as possible to aid in their recapture and re-enslavement. Willis L. Brown, “A Likely Negro and Without Fault,” Negro History Bulletin 18, no. 8 (1955): 177–79. Nelson, “A ‘Tone of Voice Particular to New England,’” S306. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- Thank you to James Duschuk for his obversions on the role of smallpox epidemics in shaping the valuation of enslaved people in the eighteenth century British Atlantic. James Duschuk in conversation with the author via video conference, October 6, 2022. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- Michael Schreiber, “Philadelphia’s Rich Maritime History,” Philahistory.org (blog), August 19, 2019, https://philahistory.org/2019/08/29/philadelphias-rich-maritime-history/. ↵

- Linde Lunney, “Dunlap, John,” in Dictionary of Irish Biography, published October 2009, last revised October 2009. https://www.dib.ie/biography/dunlap-john-a2848. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore close their April 29, 1768 letter with the line, “We shall expect the Stove by the first Opportunity from your Port.” Their stove order from William Dunlap is referenced in, at least the following letters: John Dunlap to William Brown and Thomas Gilmore, letter, September 15, 1768, Brown and Gilmore, printers: C-15778, MG 24 B 1, Library and Archives Canada, https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c15778/641. William Dunlap to William Brown and Thomas Gilmore, letter, 1768, Brown and Gilmore, printers: C-15778, MG 24 B 1, Library and Archives Canada, https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c15778/657. William Dunlap to William Brown and Thomas Gilmore, letter, February 28, 1768, Brown and Gilmore, printers: C-15778, MG 24 B 1, Library and Archives Canada, https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c15778/649. William Dunlap to William Brown and Thomas Gilmore, letter, July 1767, Brown and Gilmore, printers: C-15778, MG 24 B 1, Library and Archives Canada, https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c15778/646. ↵

- Brown and Gilmore to Dunlap, letter, April 29, 1768. ↵

- J. Dunlap to Brown and Gilmore, letter, September 15, 1768. ↵

- J. Dunlap to Brown and Gilmore, letter, September 15, 1768. ↵

- For coverage on the role of printers in Transatlantic Slavery, see: David Waldstreicher, “Reading the Runaways: Self-Fashioning, Print Culture, and Confidence in Slavery in the Eighteenth-Century Mid-Atlantic,” William and Mary Quarterly 56, no. 2 (April 1999): 243–72. Jordan E. Taylor, “Enquire of the Printer: Newspaper Advertising and the Moral Economy of the North American Slave Trade, 1704–1807,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 18, no. 3 (2020): 287–323. For coverage on William Brown and Thomas Gilmore role as enslavers and promoters of slavery, see: Nelson, “A ‘Tone of Voice Peculiar to New-England,’” S03–S16. ↵

- Eve Tuck, Allison Guess and Hannah Sultan, “Not Nowhere: Collaborating on Selfsame Land,” Decolonization:Indigeneity, Education & Society, June 26, 2014, https://decolonization.wordpress.com/2014/06/26/not-nowhere-collaborating-on-selfsame-land/. ↵

- Robyn Maynard and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “On Letter Writing, Commune, and the End of (This) World,” in Rehearsals for Living (Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022), 13–14. ↵

- Nelson, “Introduction,” 7. ↵

- Nelson, “Introduction,” 4–8. ↵

- David Jay Minderhout and Andrea T. Frantz, Invisible Indians: Native Americans in Pennsylvania. (Amherst, New York: Cambria Press, 2008), 53. ↵

- Turnbull, “William Dunlap, Colonial Printer, Journalist, and Minister,” 145. ↵

- For example, the colonial Virginia-Pennsylvania border was unresolved between 1681-1863. See: “Virginia-Pennsylvania Boundary,” Virginia Places, accessed January 14, 2024. http://www.virginiaplaces.org/boundaries/paboundary.html. ↵