Creating Affordable Content Programs

Ron Joslin, John Meyerhofer, Angi Faiks, and Teresa Fishel

by Ron Joslin (Macalester College), John Meyerhofer (College of St. Benedict/Saint John’s University), Angi Faiks (Macalester College), and Teresa Fishel (Macalester College) (bios)

Introduction & Background

Colleges and universities are increasingly engaging with open access (OA), open educational resources (OERs), and open textbooks. At Macalester College, an exclusively undergraduate institution of roughly 2,000 students, we have long been involved with OA initiatives. We believe strongly in the free and fair exchange of information, which is the foundation of open access.

In this chapter we focus on our experience supporting OERs, which, according to the Hewlett Foundation (n.d.), are “teaching, learning and research materials in any medium—digital or otherwise—that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions” (“Open Educational Resources: OER Defined”). Our background with OA initiatives has served as the foundation for our foray into OERs and open textbooks.

Our first entree into OA was supporting SPARC (originally the Scholarly Publishing and Research Coalition) in 1997; we have been a member since 2002. Although our initial efforts were focused on lowering journal costs, for two decades we have supported a variety of OA initiatives in order to encourage positive changes in scholarly publishing and wide dissemination of scholarly and creative works. We developed an institutional repository that provides OA to student honor projects, award-winning papers, peer-reviewed OA journals, and faculty publications. Resources in our repository have been downloaded more than 2 million times from locations around the world. We have expanded our OA support to include open monograph publishing initiatives such as Lever Press, Open Book Publishers, and Knowledge Unlatched.

We explain here how we have educated our community on OERs, developed tactics for engaging with faculty partners, and created of a set of resources to support anyone interested in working on an OER project.

We explain here how we have educated our community on OERs, developed tactics for engaging with faculty partners, and created of a set of resources to support anyone interested in working on an OER project. We conclude with lessons learned and next steps. While we write from our small-college perspective, our insights will resonate with all higher education institutions with a similar goal of wanting to meaningfully participate in the OA, open textbook, and OER movements.

Starting the OER Discussion & Finding our Motivation

As we started exploring OERs, we looked at initiatives at other institutions of higher education, and attended OER and open textbook discussions, meetings, and conferences. At these gatherings, we found ourselves among librarians and faculty from predominantly large public universities or community college systems, and couldn’t find many from our peer institutions who were exploring OERs. It appeared we would be charting a new path for small, liberal arts colleges.

We launched our OER initiative with the belief that we had something valuable to offer to this effort. We began by engaging in a number of activities to encourage OER and open textbook adoption. In January, 2015, SPARC offered an OER Workshop at ALA Midwinter in Chicago entitled “Tackling Textbook Costs through Open Educational Resources: A Primer,” led by Dr. David Wiley and Dr. David Ernst. The session focused on how library staff can leverage OERs to increase textbook affordability and on how to create a campus action plan. After attending this workshop, we sponsored a faculty luncheon discussion in the spring of 2015, inviting Dr. Ernst and Macalester economist Tim Taylor to discuss their involvement with open textbooks.

That summer we joined the Open Textbook Network (OTN), a group of libraries at higher educational institutions that facilitates the adoption of open textbooks, the development of expertise and best practices to support such adoptions, and the creation of a methodology for tracking the impact open textbooks have on student success. Joining the OTN was our first attempt to promote the use of OERs and provide access to high-quality resources to support scholarship and teaching at Macalester College. With the OTN, we again found we were the only small, liberal arts college participating.

At the spring 2015 luncheon, mathematics faculty expressed interest in open textbooks. They surveyed their students and found, contrary to expectations, that their students didn’t believe textbook costs were a concern on our campus. In an email to us, one faculty member said that students are not worried about costs because they have other avenues for obtaining texts. (K. Saxe, personal communication, March 14, 2015) We assumed this attitude was an outlier and that most of students would disagree that textbook costs were not a concern. The same sentiment, however, was echoed in further conversations with students.

In October 2015, we co-sponsored with the Macalester College Student Government (MCSG) a well-attended forum during Open Access Week. We highlighted the extreme rise in textbook costs compared with the standard cost of living, explained open textbooks, shared the advantages of using open resources, and expressed how these could be a solution to the problem of textbook affordability. During the discussion period, students said, with near unanimity, that textbook affordability was not an issue for them. While they considered cost an issue for many U.S. college students, they did not perceive it as a problem for themselves individually or, anecdotally, among their local campus cohort. We are quite certain that this perception is not due to the common misconception that students at our small, private, elite college do not suffer from financial pressures. Our institutional financial aid data show that in fall 2017, 70% of U.S. first year students at Macalester received need-based financial aid, and the average need-based financial aid package covered 75% of our comprehensive fee (tuition, fees, room, and board) (Macalester College, n.d.).

It is more likely that the relative lack of concern regarding textbook costs is tied to factors unique to our campus. For example, the launch of an extremely successful textbook reserve program developed by student government and hosted by the library has had an impact on the perception of burdensome textbook costs. This program funds the purchase of the most expensive and widely used textbooks, and places them on reserve in the library. Textbooks in economics, biology, and math are the most popular resources in the buying program. Launched in 2009, this program has been extremely successful; textbooks were checked out 11,342 times in 2017, and the textbooks available increased from four titles in the program’s first year to 43 (252 copies) in the fall of 2017. Another option for our students is Macalester’s Textbook Advance Program, which pays textbook costs for selected students who have a demonstrated need. Finally, the Macalester bookstore hosts “Bingo for Books” events which award students prizes, including money for textbooks. With these various safety nets in place on our campus, and other informal processes developed by students, we realized that the issue of textbook costs was not a selling point for OERs among many of our students and faculty.

While the motivation for many OER initiatives is to reduce textbook costs, we thus realized that our motivation would stem for our belief in the benefits of OA. The OER movement is closely aligned with our long-time efforts to increase OA for scholarly works and advocate for open resources for all. We did discover, however, that our students are concerned that the content of textbooks in their classes is often lacking, irrelevant, or skipped over by the professor. So while they do not have serious concerns about acquiring a book, the value of that book may be in question. All of these factors fueled our efforts and our realization that a multi-pronged approach to fostering OER use on any campus is advisable in order to address a variety of concerns, needs, and motivations.

Shifting our OER Message

After learning from our community their motivations and sentiments around open textbooks, we shifted the focus of our OER discussions. We emphasized the flexibility and customizability that open resources provide. Conversations with faculty about the flaws of commercially published textbooks resonated with their experiences. Faculty expressed frustration with new editions of textbooks that had little or no substantive change to the content, the lack of interdisciplinary content, and the dearth of adequate undergraduate textbooks in certain research areas. All of this was fruitful ground when we introduced the power behind open licensing as illustrated by David Wiley’s 5Rs: Retain, Reuse, Revise, Remix, and Redistribute (Wiley, n.d.)

Many of our faculty were excited that they could intertwine and customize OERs, and intrigued by the possibility of adding unique multimedia and interactive content. All of this was highly appealing to the “rugged individualism” that is part of our faculty culture.

Many of our faculty were excited that they could intertwine and customize OERs, and intrigued by the possibility of adding unique multimedia and interactive content. All of this was highly appealing to the “rugged individualism” that is part of our faculty culture. We saw, then, an opportunity to combine all of our goals: we wanted to encourage OER use, students wanted textbooks that were more closely integrated with courses, and faculty wanted learning resources that more closely aligned with their teaching methods and goals.

Having discovered emerging interests in OERs among our faculty, we shifted our work to identifying barriers and developing the resources and expertise needed to overcome those barriers. For faculty to actually get started we needed to create pathways to successful development of open textbooks and other OERs.

Overcoming Obstacles

As revealed in the Babson Survey Research Group’s study Opening the Textbook: Educational Resources in U.S. Higher Education, 2015–16 (Allen, 2016.), it isn’t easy to create OERs or open textbooks. Our faculty identified similar barriers. While many, for example, had heard the phrase “open education resource,” they did not have a good understanding of what an OER or an Open Textbook was, and were uncertain where to search for and locate OERs in their discipline areas. If they were aware of OERs, they were doubtful about the quality. And while they were excited by the possibility of mixing and adding to open content, they were concerned about the time it would take, their own lack of experience in authoring a textbook, and their lack of technical knowledge.

To address these concerns we collaborated with our academic technologists to hold a full-day, hands-on workshop for faculty interested in exploring OER adoption or creation. Twenty faculty, representing every division, attended the workshop. They learned about Creative Commons’ licensing, strategies for identifying OERs in their areas, and software available for creating OERs and open textbooks, and were able to explore Pressbooks, a WordPress plugin frequently used in the creation of open textbooks. By sharing these resources and answering specific questions around OERs, we hoped faculty would feel more comfortable about considering projects. While the workshop was well received, and the audience engaged with the activities, our faculty were still hesitant to proceed on their own. They needed additional support to develop and proceed with their project ideas.

Developing an OER Toolkit & Incentive Program

Wanting to find a way to address these concerns and help faculty more easily navigate the steps and tasks involved with an OER project, we landed on the concept of an OER Toolkit. This Toolkit would be organized by topic areas such as finding OER content, understanding and using open licensing, layout and design, dealing with accessibility issues, and more. We would collect and organize existing content, resources, and tools for creating OERs, and include information on people available at Macalester to assist with projects. Essentially, the Toolkit would be an in-depth, guided version of the workshop. We also envisioned teams of specially-trained students and staff to assist faculty with building multimedia content. Faculty at institutions like ours benefit greatly from personalized and tailored assistance on projects such as these. The Toolkit would serve as a sort of recipe, offering faculty step-by-step guidance in the adoption or creation of an OER, and as with any recipe, users could customize it to meet their individual needs.

Wanting to find a way to address these concerns and help faculty more easily navigate the steps and tasks involved with an OER project, we landed on the concept of an OER Toolkit.

To encourage faculty, we developed a stipend program to accompany the Toolkit. Stipends would provide start-up funding to create and implement an OER project. Recipients would receive an initial consultation with a resource team including the OER Coordinator, the subject specialist librarian, and an academic technologist to discuss strategies for successful completion of their OER project. The intention behind the Toolkit and stipend program was to help faculty feel less daunted by the tasks involved in OER adoption or creation and to demonstrate library staff expertise and commitment.

Pilot OER Project

To develop and test our Toolkit concept, we envisioned working with a faculty member to develop an OER or open textbook. By working side-by-side on a project, we would create a better Toolkit. Our goals for the pilot project were to:

- document the tools, resources, and services needed and provide them wherever possible;

- document and create best practices for frequently encountered issues;

- test open textbook development software and create support documentation;

- successfully complete our first OER project on campus;

- widely share the story of this project and the resulting OER Toolkit to encourage others to complete similar projects.

We then needed to find a faculty partner. One faculty member stood out for us as a candidate for our pilot project. Professor Britt Abel, German and Russian Studies, had attended our hands-on workshop and had discussed with us her idea for creating an open learning resource for first-year German-language students. She was dissatisfied with the content of the commercial textbooks available. Her vision, developed in partnership with a faculty colleague—Professor Amy Young—at a peer institution, was a multimedia, interactive resource allowing for student engagement beyond simply reading text on a page. Abel, Young, and Joslin (2017) best articulated the goal in their application for a National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH) grant for Grenzenlos Deutsch: an Inclusive Curriculum for the German Classroom:

An equally important goal is to employ more diverse voices and real-world contemporary perspectives in our curriculum. For that reason, we include content areas on social and environmental sustainability, non-traditional families, and diverse expressions of “culture.” For example, rather than only including audio/video tracks of native German speakers, a trend that limits the diversity of the course material, we include non-native speakers with high proficiency as well as native speakers to reflect today’s real-world experience of speaking German in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Similarly, at a time when gender nonconforming students are struggling to find the vocabulary and tools to represent themselves in the classroom and beyond, this curriculum also addresses the question of gender and language head on in a series of cultural notes and in the presentation of some recently developed usages to avoid gendered nouns (i.e., Studierende rather than Studenten und Studentinnen). The digital platform will enable us to update these terms easily as they evolve. In short, students will be able to see themselves and the world they experience reflected in the curriculum.

We had found our faculty OER champion who embodied the rugged individualism and commitment that we knew would help keep the project moving forward and whose concept matched our broad mission to create something for the greater good.

To aid in our efforts, we applied for and received grant funding from the Mansergh-Stuessy Fund for College Innovation, a family foundation which provides seed grants for innovative ideas developed and tested at selected local liberal arts colleges. In addition, we joined with our faculty partners in applying for an NEH grant, which was awarded to us in 2017. This funding helped support the ongoing development of the full German language learning resource and our OER Toolkit.

Working with the German project reaffirmed the benefits of librarians partnering with faculty on OERs. We researched open software tools to meet the needs of the project, and connected faculty with them. We brought organization to the audio and visual files the faculty had already created, adding procedures for metadata, archiving, and version control. In addition, we trained a team of students to clean up image files and edit existing video and audio content. We thus developed best practices for ongoing content creation, description, and organization. The insights and knowledge gained from this partnership and pilot project served as the foundation for our OER Toolkit.

The OER Toolkit

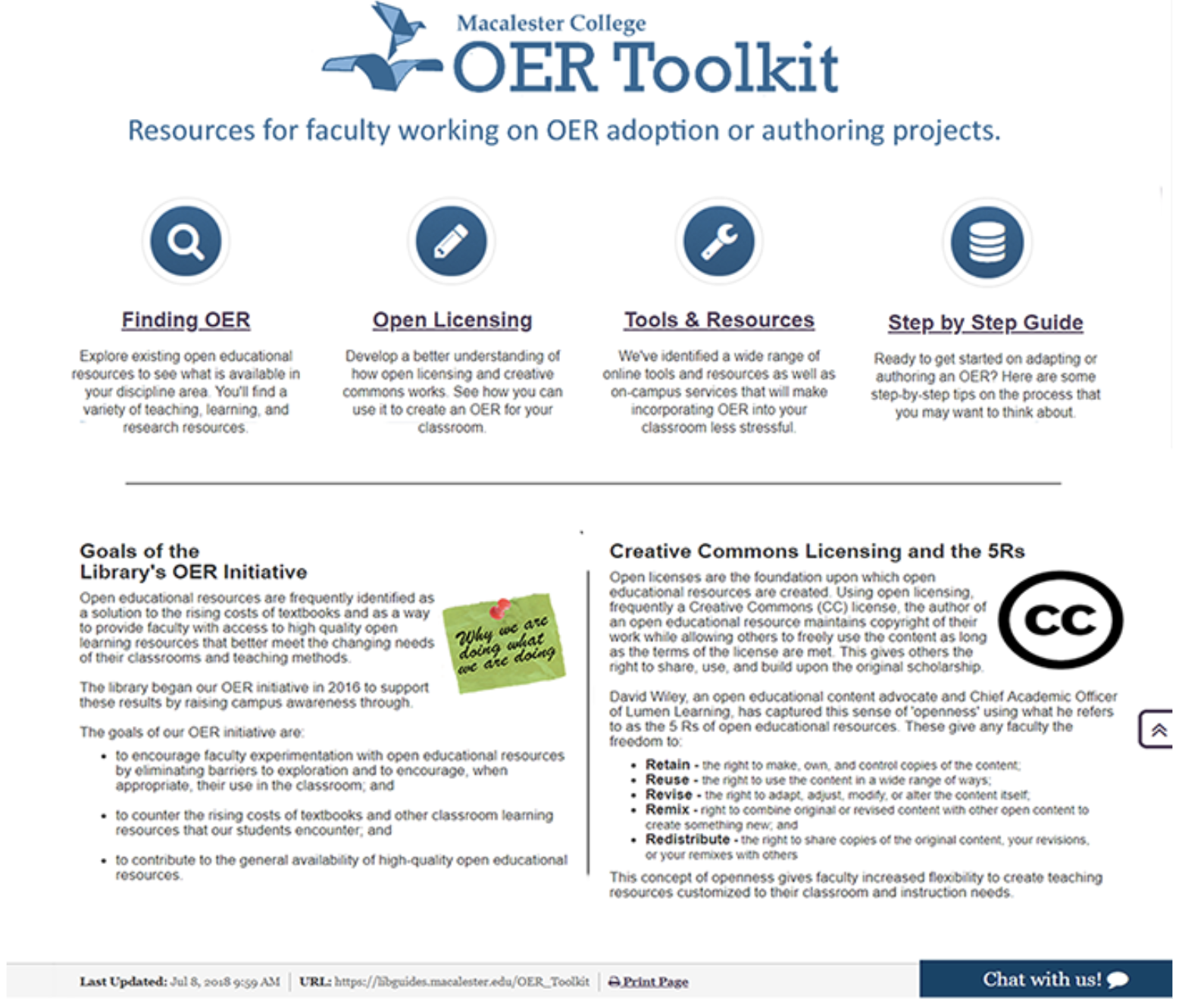

Our vision for the OER Toolkit expanded through our pilot project. The Toolkit, which is on the LibGuides platform, begins with an introduction to OERs that includes examples of OERs, myths, and misconceptions, along with David Wiley’s 5Rs. The four main sections are as follows:

Figure 1: OER Toolkit website

Finding OERs:

List of the main repositories and collections of OERs, including suggestions for evaluating quality.

Open Licensing:

Overview of open licensing, a summary of the different license types, tips for identifying the best license for a project, best practices for attribution, and methods for finding openly licensed content.

Tools & Resources:

This is the heart of the project. It is a directory and guide to tools and resources for creating a wide variety of OERs. Open source and local resources are highlighted.

Step-by-Step Guide:

This section is for those who may feel overwhelmed by the creation of OERs.

While our OER Toolkit is customized for our campus, with listings of local resources and experts, it is available under a Creative Commons CC BY SA license for all to use, adapt, and build upon.

Lessons Learned & Conclusion

In developing OERs at our small liberal arts college, we took inspiration from university and community colleges’ OER and Open Textbook projects, but had to find an approach best suited to our environment and needs. Our OER message, for example, was much more persuasive to our faculty when we switched our focus from cost savings to content customization. We capitalized on our strengths as we planned our OER development strategy, especially our close working relationships with faculty and staff, and our distributed team approach to projects.

Faculty concerns about launching an OER project led us to find ways to lessen barriers, both real and perceived. We developed the idea of the OER Toolkit and sought a faculty champion for a pilot project. We learned a great deal in working with the faculty developing the German curriculum modules, as reflected in our expanded OER Toolkit.

Through the pilot project and the development of our OER Toolkit we reaffirmed the value of librarian expertise for OER projects, and found that leveraging existing campus relationships and expertise eased the burden and strengthened the project.

Through the pilot project and the development of our OER Toolkit we reaffirmed the value of librarian expertise for OER projects, and found that leveraging existing campus relationships and expertise eased the burden and strengthened the project. We worked with Information Technology Services (ITS), the Center for Scholarship and Teaching (CST), our Postdoctoral Fellow in Digital Liberal Arts, and the research and instruction librarians. By taking advantage of the skills and talents among our campus partners we were able to develop a much broader, more diverse, and more useful OER Toolkit. We have heard from other institutions that collaboration across campus has been important to the success of their OER efforts, and this proved true at our institution as well.

Our OER Toolkit is still in development and will continue to go through iterative changes and improvements. It is not an end but a beginning, one we hope will help Macalester develop a viable and sustainable OER program that engages our faculty, staff, and students while furthering our mission to support OERs well beyond our institution. We believe our program serves as a model that other smaller institutions could emulate for the benefit of their community members and of society as a whole.

Next Steps

We wish to further our message of the benefits of OA and OERs by connecting with our campus’ emphasis on social justice, internationalism, multiculturalism, and service to society. A central goal of the German OER project, for instance, is to create a more inclusive and diverse textbook than is currently available. This potential offered by OERs and open textbooks resonates with our faculty.

We also want to develop a faculty mentoring program so faculty can support each other in their OER efforts, sharing their experiences, failures, and successes. We would like to create a culture on campus that welcomes and rewards creation, experimentation, and use of OERs. Ideally, this culture would also incorporate the talents of our students. By involving students in the development of OER materials, we would foster an atmosphere of collaboration and engagement, provide unique e-publishing experiences, and enhance our OER structure by further distributing the workload. This ties neatly in with our campus’ long history of student-faculty scholarship endeavors. We hypothesize that students working on an OER or open textbook, while also learning the content, would have a deeper learning outcome.

There has been much discussion about peer review and its role in OERs. In particular, many OER detractors believe these materials do not have the same academic rigour as standard textbooks. At a smaller institution like Macalester, establishing a peer review program for our OER materials is not feasible. Instead, we are exploring a community peer review program with other liberal arts colleges. This network could also be used as a source for OER collaborators. By developing pathways for distributing and sharing the work, the creation of OERs and open textbooks is much more realistic for small college faculty.

We are committed to supporting the creation of OERs and open textbooks that foster new and innovative student learning. We look forward to working with our network of peer institutions to expand our capabilities and to share expertise and technical solutions.

References

Abel, B., Young, A., & Joslin, R. (2017). Grenzenlos Deutsch: An inclusive curriculum for the German classroom. National Endowment for the Humanities Digital Humanities Advancement Grant Application.

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2016). Opening the textbook: Educational resources in U.S. higher education, 2015-16. Retrieved from https://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/oer2016/html/openingthetextbook_format.htm

Macalester College. (n.d.). Financial aid & tuition. Retrieved from https://www.macalester.edu/admissions/financialaid/

Wiley, D. (n.d.) Defining the “open” in open content and open educational resources. Retrieved from http://opencontent.org/definition/

William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. (n.d.). Open educational resources. Retrieved from https://www.hewlett.org/strategy/open-educational-resources/

Author Bios:

Ron A. Joslin is the Research and Instruction Librarian to the Natural Sciences, Mathematics, Statistics and Computer Science. He has taken the lead on open textbook initiatives and is the Macalester representative to the Open Textbook Network. He has participated in many professional development opportunities related to open textbooks and has led several workshops and presentations on open textbook adoption and creation both on campus and at library conferences.

John Meyerhofer is the former Digital Scholarship Librarian and worked with faculty and served as the administrator for the institutional repository as well as providing support for our Digital Liberal Arts projects with faculty and students. John is now Systems Librarian, Hill Museum and Manuscript Library, CSB/SJU (College of St. Benedict/Saint John’s University).

Angi Faiks is the Associate Library Director and her professional interests include library innovation, information access and literacy advocacy, libraries as community space, maker movements, and working towards diversity in librarianship and STEM. She takes enormous pride in the thoughtful creativity and innovation exemplified by librarians in meeting the needs of community members. She focuses on fostering positive change, encouraging bold new ideas, and building partnerships in order to ensure excellence in what the library offers today and well into the future.

Teresa A. Fishel is the Library Director and a long-time advocate for open access and the role of academic libraries in publishing. In addition to workshops on open textbooks, she has done presentations on the role of academic librarians in open access publishing initiatives and on digital publishing opportunities for faculty.