Affordable Content Models

Serdar Abaci and Anastasia S. Morrone

by Serdar Abaci and Anastasia S. Morrone (both from Indiana University) (bios)

Introduction

Hyperinflation in overall college costs and in textbook prices in the last decade is no secret, as demonstrated by extensive coverage in several major news reports. High textbook prices are deterring students from buying required textbooks or taking courses that have high-priced textbooks. The cost of textbooks, in other words, gets in the way of learning, and derails students from degrees they want to pursue in college.

Many universities and even state systems (Acker, 2011) are trying to lower the cost of textbooks for students. Indiana University (IU) started a pilot e-text program in 2009 to make publisher/commercial content more affordable. The program is based on an inclusive access model, addressed in more detail in the previous two chapters of this book. After a successful pilot phase, the IU eTexts Program moved into full production. As of March, 2018, it has served close to 200,000 students in over 9,000 course sections, and saved them more than $13 million in textbook costs. In this chapter, we explain the Indiana University eText model, the research efforts behind the program, support for faculty and students, and the factors behind the program’s success.

Indiana University’s eText Model

When it started as a pilot in 2009, the Indiana University eTexts program had four primary goals:

- Lower the cost of course materials for students

- Provide high-quality materials of choice for faculty

- Enable new tools for teaching and learning

- Shape the terms of sustainable models that work for students, faculty, and authors

These goals have served us well. We continue to maintain them, and have been very successful in meeting them. As we continue, we have added a fifth goal of continued program growth—both in the number of participating publisher/vendor partners and in the number of faculty/students/classes using at least one e-text through this program. We also want to take full advantage of the research opportunity provided by the captured data. This will help us inform best practices for teaching and learning with technology, and contribute to the research-driven conversation regarding student engagement with digital reading materials.

Several distinct components of the IU eTexts program contribute to its success:

- Publisher agreements

- Workflows for ordering textbooks

- Outreach efforts

- Focus on a universal e-reader

- Cost savings

- Offerings beyond publisher content

Publisher Agreements

IU has contracts with more than 30 publishers, ensuring significant cost savings. IU is also a founding member of the Unizin consortium, a group of like-minded institutions with a common goal of enhancing learning success with digital technology and resources. As an early adopter of a university-wide affordable eText program, IU has shared its knowledge and experience with the consortium and other member institutions. As a result, the consortium is now able to offer similar publisher contracts and prices for its member institutions.

IU’s agreements with the publishers involve an inclusive access model, through which all students acquire day-one access to a digital version of the textbook (Straumsheim, 2017). Course instructors have the option to choose an eText for their courses. Once an instructor opts in by submitting an order request, all enrolled students are assigned the eTextbook by default. Each student’s bursar account is charged the corresponding e-text license fee and e-reader license fee, and they get access to the e-textbook(s) on or before the first day of class.

IU’s agreements with the publishers may differ from those of other institutions in that they allow unlimited printing of e-textbook pages (up to 50 pages at a time). If students prefer a bound copy, they can order one for a nominal fee.

IU’s agreements with the publishers may differ from those of other institutions in that they allow unlimited printing of e-textbook pages (up to 50 pages at a time). If students prefer a bound copy, they can order one for a nominal fee. In addition, per IU’s agreement, student access to e-textbooks does not expire after the course is over. Students maintain access as long as they are enrolled at Indiana University.

In IU’s e-text model, students may elect to opt out of the e-text fees for a class, providing three eligibility criteria are met:

- The exact same ISBN must be legally available elsewhere,

- They must have never accessed the e-text, and

- They must submit their request within 30 days of enrolling in the class.

When students register for a course, they see whether it has an e-text. They can opt out of the e-text at the class registration phase, but are discouraged from doing so. IU actively discourages opt-outs through both student and faculty education. In the online opt-out request form, students are required to read a series of statements explaining the academic risks of opting out, such as losing access to additional content their instructor might provide in the e-text, and losing the ability to interact with their classmates and instructor within the e-text itself. On the faculty side, teaching and learning support staff are working to teach faculty how to make effective use of e-texts, so it is less likely that students will opt out.

As campus bookstores are typically involved in selling physical textbooks and have contractual agreements with publishers and universities, these terms need to be revisited, and potentially re-negotiated, for bursar-billed models for digital course materials.

Workflows for Ordering Textbooks

We mimic, as much as possible, the traditional textbook-ordering models familiar to faculty. We set and advertise an ordering “window” for each upcoming term, corresponding to the academic calendar. We expect faculty to submit their orders before students begin to enroll for the term, in compliance with Higher Education Opportunity Act recommendations. This allows us to include an automated notation of the e-text requirement in the Schedule of Classes and in the registration system, for students to see as they plan and enroll for the term.

Because the IU eTexts program is not affiliated with the university bookstore, we built our own ordering tool for faculty, imitating many of the familiar features of the bookstore application. This tool is open to faculty (and to select school and departmental staff members who submit orders on behalf of faculty) during the ordering window. A catalog view of available titles is always available for faculty who wish to plan ahead and view offerings. The tool also permits the electronic routing of requests for those schools and departments who wish to track, monitor, or collect e-text ordering data for internal purposes.

After an order is submitted (and, if necessary, approved), most of the remaining preparatory work is done administratively, behind the scenes. This includes automated student notations, billing, communication of the order to our publisher partners, completion by Unizin of the title setup in the Engage e-reader platform, faculty notification when the title is ready to be accessed and prepped, and enrollment calculation and reporting.

Outreach Efforts

Outreach is a multi-pronged effort at IU. The IU eTexts Program has one dedicated staff member, a Principal Business Analyst and Faculty Consultant. This position serves as a central point of contact and liaison for all project stakeholders, including but not limited to the central IT organization, faculty, students, publishers, registrars, and bursars on the eight IU campuses.

Consulting with faculty (whether they are long-time users of e-texts, just beginning to consider the option, or in between) is, easily, more than half of this person’s daily tasks. Outreach efforts take multiple forms, including a Canvas project site that serves as a repository and reference for all things related to the initiative such as announcements, ordering deadlines and step-by-step instructions, and preparation tips. In addition, regular email announcements remind faculty and staff of the coming ordering window. Campus visits are highly productive and valued efforts. The consultant visits each of IU’s eight campuses at least once each term, offering a day-long workshop for any faculty members who wish to learn more about IU’s e-texts program. The day includes general informational sessions as well as tailored training on specific issues or topics, depending on faculty, departmental, or school requests.

In addition, IU offers consultants in teaching and learning centers on each campus, as well as a group of instructional designers. There are also a few IT sub-units whose staff can communicate with faculty about the program. All of these staff are familiar with the initiative and help with outreach efforts, often working in tandem with the dedicated IU eTexts staff.

Outreach activities also take place at higher levels. The Learning Technologies executive team regularly communicates with campus leadership (i.e., provosts/chancellors and deans) to report the positive results and request their help in getting the message to more faculty. Formal and broad communications through university-wide channels are also a part of this effort. Finally, the publishers themselves help with outreach efforts. Sales representatives regularly work to transition their new and existing faculty clients to e-texts, often working in tandem with the Principal Business Analyst and Faculty Consultant.

Finally, IU has created channels through which to share information about its eTexts Program with people outside the university. IU eTexts (etexts.iu.edu) is a public-facing website, offering information for both faculty and students, as well as for anyone who wishes to learn about our program. It serves as an information hub for all news related to e-textbooks. In addition, we share our research findings in the research section, along with relevant research literature.

Finally, IU has created channels through which to share information about its eTexts Program with people outside the university. IU eTexts (etexts.iu.edu) is a public-facing website, offering information for both faculty and students, as well as for anyone who wishes to learn about our program.

As eTexts at IU became more successful, we began fielding questions from our higher education colleagues who were considering a similar solution to their schools’ textbook conundrum. In an effort to share insights and lessons from our e-text model with the higher education community, we recently published a free ebook eTexts 101: A Practical Guide. The book’s first section relates the story of how IU developed and implemented its eTexts program, the second offers perspectives from several publishers who have participated in the program, and the third provides reports from other universities on work they are doing to address the textbook issue.

Focus on a universal e-reader

IU uses a single e-reader platform for its e-text program, providing a unified e-reading experience for our students. Provided by the Unizin Consortium, the Engage e-reader is a publisher-agnostic platform that integrates with the Canvas learning management system (LMS). The platform includes the following features for student users:

Search

Bookmark

Highlight text

Annotate the highlighted text (and create tags)

Ask the instructor a question (convert annotation to question)

Add page notes (without highlights)

Share notes and highlights with instructor and classmates

Read offline by downloading the content to your device

The Unizin Engage e-reader also provides features for instructors, allowing them to share notes and highlights with students, interact with students within the e-text through the question and answer feature, and use reading and engagement analytics to evaluate student- and class-level reading and markup usage.

Cost Savings

Publishers offer significant cost savings in exchange for the promise of nearly 100% sell-through rates. The formal savings calculation reflects the difference between the “print list price” and the negotiated IU e-text price for the publisher content. As of March, 2018, IU student savings on textbooks amount to $26,612,485. We do, however, recognize that many students do not pay the full list price for paper textbooks when they purchase online, buy used copies, or recoup some of their costs by reselling their texts after the semester is over. An article from the New York Times highlights that actual student spending on course materials, including textbooks, was about half the actual cost of the textbooks and related course materials (Carrns, 2014). We therefore divide the calculated savings by two and report that total as a more accurate representation of student savings. Consequently, we claim that our students have saved more than $13 million since IU’s e-texts program started in the spring of 2012.

Offerings Beyond Publisher Content

While IU’s e-text model is driven primarily by publisher content, it is not limited to this content. Instructors may choose to deliver their own content (e.g., faculty-created, fair use, OER, etc.,) through the Engage e-reader platform and take advantage of its interaction and data analytics features. The platform can deliver content in many formats, including PDF, Word, PowerPoint, and Excel. Unizin is currently developing the next version of Engage, which will also offer multimedia content via ePUB format.

Data on Reading Behaviors and on Experiences of Faculty and Students Using E-texts at IU

Beyond providing course-based reading and engagement analytics for instructors, use of a single reading platform for all e-textbooks provides opportunities to analyze rich data on student reading behaviors. Here we summarize our research findings regarding faculty and student experiences and look at what they mean for teaching and learning with e-texts.

Instructor Engagement with E-texts

As researchers at IU, we published an EDUCAUSE Review case study in early 2015, investigating the effects of instructor engagement with e-texts on student use of e-texts (Abaci, Morrone, & Dennis, 2015). Self-reported data on e-text usage was collected from students during the pilot phase of the program, and indicated that, overall, students whose instructors actively used e-texts (i.e., shared highlights, annotations, and notes) read, annotated, and reported learning more from e-texts than students whose instructors did not actively use e-texts.

Based on these findings, we identified and interviewed instructors who were using e-text markup features (i.e., highlights, annotations, page notes) in order to understand their motivations and how they use e-texts in their teaching. In addition to the cost savings, instructors gave four reasons for adopting e-texts:

- Guaranteed access to e-texts by all students when the semester starts

- Ability to share highlights and notes with students directly on the e-texts

- Ability to use e-texts more effectively during class time

- Ability to view student engagement in readings

The data confirmed that when instructors engage with e-texts, so do their students. In other words, instructors play a key role in adoption and effective use of e-texts for learning by modeling active e-text use and creating meaningful interaction around the content.

Instructors in our study used shared highlights and notes to communicate with students about the reading materials. Use of these interactive markup tools can help both in-class activities and outside review and study for exams. The data confirmed that when instructors engage with e-texts, so do their students. In other words, instructors play a key role in adoption and effective use of e-texts for learning by modeling active e-text use and creating meaningful interaction around the content.

Student Engagement with E-texts

Following up on our earlier research and having access to universal e-reader data such as page views and markups, we turned our attention to actual usage data to gain a deeper understanding of student and instructor engagement with e-texts at IU. We published another case study in EDUCAUSE Review, reporting on e-textbook usage by undergraduate students in residential courses between 2012 and 2016 (Abaci, Quick, & Morrone, 2017). The usage data include page views and use of markup and interactive features such as highlights, notes, questions, and answers.

This study showed that, in a typical week, students access their e-texts more after 5 pm Monday through Thursday, indicating that they use e-texts mainly as a self-study resource. In a typical semester, students read or viewed pages more in the first four weeks and less in later weeks. Highlighting was the feature most used by students, while interactive markup features were used minimally. We also found that higher engagement with e-texts (reading and highlighting) correlated with higher course grades: high-performing students (A and B grades) read and highlighted significantly more than average-performing students (C grades), who read and highlighted significantly more than poor-performing students (D and F grades).

Faculty and Student Use of and Experience with E-texts at IU

In the fall of 2016, we conducted a university-wide Learning Technologies survey using a random sample of all students, faculty, and staff. The survey’s purpose was to assess awareness and use of specific teaching, learning, and collaboration services/technologies provided by University Information Technology Services. Twenty-five percent of the faculty sample and 10 percent of the student sample from three different campus profiles (Bloomington, Indianapolis, and regional campuses) responded. The surveys each included a section on e-text use, asking respondents if they used an e-text, whether they were aware of markup and interactive features, and what they liked most and least about e-texts.

Faculty Use and Experience

Of the 222 faculty who responded to this section of the survey, 52 percent found it very or extremely important that every student in their class have the correct version of the required textbook on the first day of class. Only 25 percent had used an e-textbook through IU’s e-texts program. Among these previous program participants, nearly half (n = 24) taught one course with an IU e-text. Previous users of e-texts were also asked if they were aware of the features offered by the e-reader platform. More than half of these faculty knew they could make their own notes within the e-texts (60%) and access their e-text offline (55%), and nearly half (45%) were aware that they could see and answer student questions within the e-texts.

The faculty who indicated previous use of e-textbooks through IU’s e-texts program were asked to comment on what they liked most and least. Thirty faculty commented on their positive experience. The major themes emerging from these comments included low cost of the e-textbooks, convenience, inclusive access to e-textbooks (all students acquire), and markup and interactive features of the e-reader platform. Twenty-seven faculty also commented on what they liked least about their experience. Their responses did not illustrate in any major theme; rather, they highlighted a variety of concerns including students’ dislike of the e-texts and mandatory e-text fee, faculty’s own preference for paper textbooks, navigation or having to scroll on a page, and slow page load.

The faculty who reported no e-textbook use through IU’s e-texts program were asked to comment on barriers keeping them from using e-texts and on incentives that may encourage them to use e-texts in the future. The majority (66%) commented on the barriers, and several themes emerged. Thirty-six faculty noted that they haven’t used e-texts because they do not require traditional textbooks for their classes or because e-texts would not work for their particular courses. Eighteen faculty indicated that they did not know anything or enough about IU’s e-texts program to consider participating. Sixteen faculty who knew about the program noted that their textbook choices were not available in the e-text catalog. Other notable comments included preference for paper textbooks (n = 8), cost of e-texts to students (n = 7), and not being able to keep the e-texts forever as a reference (n = 6).

When asked for one thing that would encourage them to use IU e-texts in their classes, 87 faculty made comments but 11 showed no future interest. Comments from those who showed interest mainly asked for title availability (n = 18), lower cost or still better prices (n = 15), and more information on or sample use of e-text (n = 14). Other notable comments included departmental buy-in, more time to explore e-texts, and adding online homework apps to e-texts.

Student Use and Experience

Forty-eight percent of the student respondents (n = 875/1,816) indicated that they had taken at least one course that used an e-text. As a follow-up question for these students, we asked if they were aware of the interactive and markup features of the e-reader platform. While 57 percent of respondents knew that they could take their own notes within the platform, only 33 percent realized they could ask their instructors questions within the platform. In addition, only 40 percent were aware they could read their e-text offline, even when not connected to the Internet. These numbers indicate room for improvement in terms of increasing awareness of the e-text platform features.

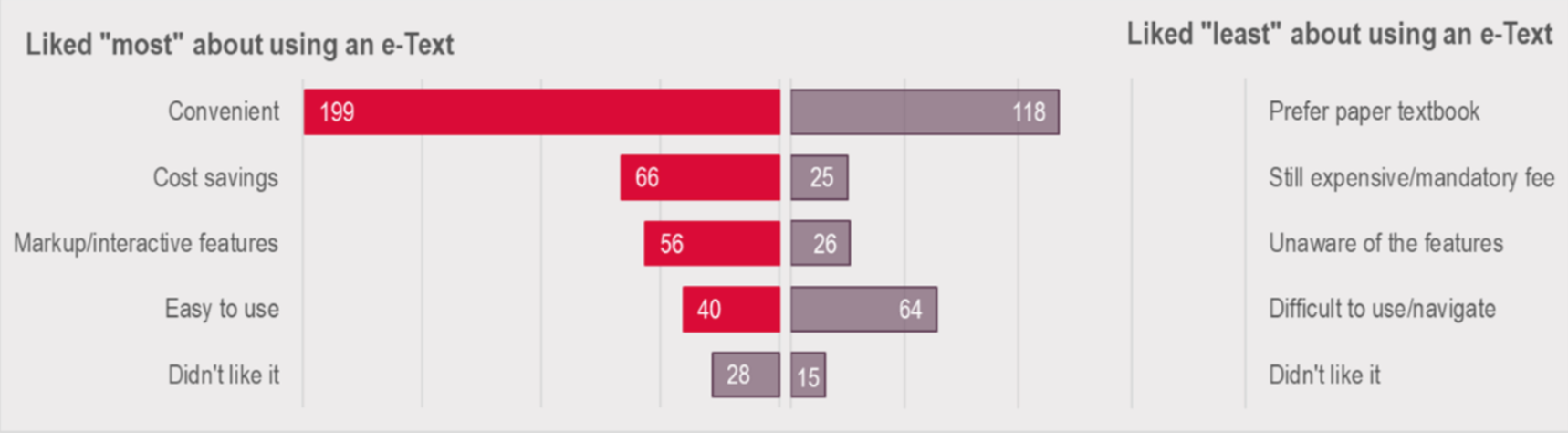

We also asked students who have used an e-text to respond to two open-ended questions regarding what they liked most and least about their experiences. A total of 379 students commented on what they liked most; a total of 376 students commented on what they liked least. These comments were coded by two of the authors with 95 percent inter-rater reliability. Several themes emerged from the positive and negative comments (Figure 1).

Nearly 200 students noted that they liked e-texts because of convenience, particularly not “having to lug around a physical textbook” and having an e-text “accessible at any time.” In contrast, 118 students preferred physical books over digital books, noting that they still “like physical books” or “prefer to read on paper versus on screen for studying.” As noted earlier, students have the option to request a print-on-demand copy of their e-texts through IU’s e-texts program.

Sixty-six students expressed that they were pleased with e-texts because the program helped them save on their college costs. Therefore, “low cost” and “affordability” were appealing. On the other hand, 25 students argued that e-texts are still expensive, or they did not like having to pay a mandatory e-text fee once their instructor signed up for an e-text. Another comparable theme between likes and dislikes was the lack of understanding about markup and interactive features of the e-reader platform. Fifty-six students praised the features as contributing to their positive experience. Comments referenced “ease of searching,” “adding self-notes,” and “important information is highlighted.” By comparison, 26 students wrote negative comments such as “can’t write in” or “can’t add note or highlight,” which indicated a lack of awareness of the markup and interactive features. Had they known about these features, they might have had a more positive experience.

Regarding another theme, 40 students indicated they found the platform easy to use, while 64 students found it difficult to use or navigate, particularly when flipping back and forth through the pages. Finally, 43 students explicitly stated that they did not like e-texts, without offering a reason.

Educational modules to Promote Effective Use of E-texts for Teaching and Learning

Based on findings from self-reported data (Abaci, Morrone, & Dennis, 2015), we suggested earlier that there is a need for faculty professional development regarding the effective use of e-texts in classes. Our findings from e-reading data confirm that students are more engaged with e-texts when their instructors use e-texts more effectively. The survey data summarized above suggest that some students who have used e-texts through IU’s e-texts program may not be aware of all of the features the Engage e-reader offers. Because lack of awareness might be a barrier to engaging with reading materials to their full capacity, in the summer of 2017 we created a small module to educate students about the features of the Engage e-reader. While the module was created as a stand-alone course in IU’s Canvas LMS, instructors are able to easily integrate it into their course site in Canvas, if they choose to do so. The module was designed to take 15 minutes, includes both textual and video instructions, and consists of the following pages:

| Page name | Description |

| What you will learn about e-text | Introductory page to the module |

| Accessing and navigating the e-text platform (Engage) | Explains and shows how to launch the Engage e-reader and navigate within an e-textbook: zoom in and out, turn pages, jump to chapters or pages, and search for a particular term or phrase. |

| Interacting with your e-text | Explains and shows how to add highlights and notes on selected text, and notes for a specific page. |

| Interacting with your classmates | Explains and shows how to share notes with other members of the class. |

| Interacting with your instructor | Explains and shows how to turn highlighted notes into questions to instructors. |

| Accessing your e-text offline | Explains and shows how to read e-textbooks offline either by downloading the book to a device or using printed copies. |

Factors Behind Success of the IU eTexts Program

When we embarked on the IU eTexts initiative, we knew that its success would depend on several factors—the first being whether we could lower textbook costs to help make college more affordable for students. This required working with publishers to help them understand that a model in which all students acquire the e-texts—even at substantially lower costs—would not reduce their profits and, in fact, had the potential to increase profits because the used book market would no longer be needed. Today, publishers no longer have to be convinced of the value of an inclusive access model, and many now widely promote this kind of model.

Faculty Choice

When we are asked about pushback from faculty about e-texts, the response is always clear: one key to our success is that the program has always been completely voluntary. Faculty are free to choose whether to adopt an IU e-text. If they choose not to use an IU e-text, they simply order their course materials through the university bookstore process.

Another key to the program’s success is to make sure faculty wanting to adopt an e-text have a wide range of publisher choices, so they can adopt the high-quality materials that work best for their class. We did not want a scenario in which faculty could choose from only a few publishers. We currently have more than 88,000 titles available from more than 30 publishers. We also provide the option for faculty to choose an open educational resource (OER) e-text by selecting that text through the ordering portal. These texts are drawn from OpenStax and the University of Minnesota’s Open Textbook Library. There is no cost to adopt an OER e-text and no cost for use of the Engage reader.

Early Introduction of the Program

When we began the program, we spent a great deal of time meeting with faculty groups, student groups, advisory committees, faculty councils, and so on to tell them about the program and answer their questions. We also conducted open town hall meetings and invited interested faculty, staff, and students to attend. Some of the most gratifying meetings were those with student government organizations on the Bloomington (IU Bloomington) and Indianapolis (IUPUI) campuses. Student leaders were eager for ways to help students save money on textbooks, and they viewed the IU eTexts program as a way to accomplish that goal. They became strong advocates for the program, which bolstered our early efforts in raising awareness. On the faculty side, some initially had concerns that there would be a university or campus mandate to use an e-text, but when they learned that participation in the program was entirely voluntary, these concerns were alleviated.

Improving Teaching and Learning Through New Tools

A key advantage of IU’s e-text program is the use of a standard e-reader, the Unizin Engage platform. The Engage platform enables faculty and students to use and share annotations, highlights, and page notes in ways that simply are not possible with a paper textbook. As faculty become more comfortable with the platform, they are increasingly using these markup tools to extend the discourse with their students within the textbook itself. At the same time, it has also become clear that both faculty and students need additional support to effectively use the Engage reader features. The educational modules described earlier are intended to meet this need by conveying best practices in the use of e-texts for both faculty and students. The effective use of e-texts and the Engage reader has the potential to transform the educational experience for both faculty and students by making the reading experience engaging and interactive.

In summary, the IU eTexts program has provided a successful model that puts choice in the hands of the faculty, saves students millions of dollars, and provides new tools to enhance teaching and learning. It also gives us access to rich data sets, analysis of which provides key insights into teaching practices and student reading behaviors, and in turn improves learning outcomes. You can find more details about the IU eTexts program in our recently published free ebook “eTexts 101: A Practical Guide.”

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mark Goodner for his input and recommendations in the preparation of this chapter.

References

Acker, S. R. (2011). Digital textbooks: A state-level perspective on affordability and improved learning outcomes. In S. Polanka (Ed.), The no shelf required guide to e-book purchasing (pp. 41-51). Chicago, IL: ALA TechSource.

Abaci, S., Morrone, A. S., & Dennis, A. (2015). Instructor engagement with e-texts. Educause Review, 50(1). Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/instructor-engagement-e-texts

Abaci, S., Quick, J. D., & Morrone, A. S. (2017). Student engagement with e-texts: What the data tell us. Educause Review. Retrieved from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/10/student-engagement-with-etexts-what-the-data-tell-us

Carrns, A. (2014, August 8). A quandary over textbooks: Whether to buy or rent. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/09/your-money/Textbooks-whether-to-buy-or-rent.html?mcubz=3.

Straumsheim, C. (2017, January 31). Textbook publishers contemplate “inclusive access” as business model of the future. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/01/31/textbook-publishers-contemplate-inclusive-access-business-model-future

Author Bios:

Serdar Abaci is the Educational Research and Evaluation Specialist for the Learning Technologies division of University Information Technology Services. Dr. Abaci conducts research on and evaluation of teaching and learning technologies. His research interests include feedback, online learning, program evaluation, and teaching and learning technologies in higher education. Dr. Abaci received his Ph.D. in Instructional Systems Technology from Indiana University.

Anastasia S. Morrone is Professor of Educational Psychology and Associate Vice President for Learning Technologies. Dr. Morrone provides leadership for several important university-wide initiatives designed to support the transformation of teaching and learning through the innovative use of technology. Her current research interests focus on technology-rich, active learning environments that promote student motivation and learning. Dr. Morrone received her Ph.D. in Educational Psychology from the University of Texas at Austin.