Creating Affordable Content Programs

Devin Soper, Lindsey Wharton, and Jeff Phillips

by Devin Soper, Lindsey Wharton, and Jeff Phillips (all from Florida State University) (bios)

Introduction

Florida State University (FSU) is a large research university composed of over 40,000 students in 16 separate colleges and more than 110 centers, facilities, labs, and institutes. Despite the national and global momentum for open educational resources (OERs) in higher education, by November, 2016, FSU still did not have a formal OER program. At that time we also did not have a center or office of teaching and learning or a formal community of pedagogical practice. Any work, discussions, or collaborations to enhance open pedagogy or the use of OERs were occurring informally, and there was no place for instructors, librarians, or staff to share knowledge or materials. Lacking a community of practice, our campus was without an opportunity to design an open educational framework or supporting policies.

This chapter details our team’s effort to put an OER program into practice efficiently and effectively, using student- and faculty-focused initiatives.

Our situation was not unique. In fact, many campuses continue to struggle with the initial steps of planning and developing an OER program. While some OER proponents might see this as a downfall or another hurdle to climb in the open movement, we saw it as an opportunity. At FSU Libraries, we decided to take immediate action and initiate diverse pilot projects to promote and support the proliferation of OERs on our campus, with the clear understanding that we could pivot and improve these projects later if needed. This chapter details our team’s effort to put an OER program into practice efficiently and effectively, using student- and faculty-focused initiatives. We discuss the process of forming a team and establishing initial goals, our approach to launching this effort, the engagement strategies we used with faculty and students, and the challenges faced and lessons learned. We conclude by examining the impact of the program and describing our future steps.

Forming Our Team

To jumpstart an OER program, it is key to assemble a team of passionate advocates. Our initial team was comprised of four faculty librarians: a distance librarian, a science librarian, an instruction librarian, and our scholarly communication librarian, who led the group. This was an unconventional arrangement, as committees and teams within our organization usually remain confined within a unit or department.

Our divergent goals and experiences, which drove our individual interests in the project, illustrate how OERs provide innovative solutions for diverse problems, and can bring together wide-ranging stakeholders with multifaceted perspectives. As an example, our extended campus and distance services librarian became an OER advocate due to her experience with our international study centers. During her visit to the European campuses in the summer of 2015, she repeatedly heard from instructors that students were not travelling overseas with their textbooks, shipping overseas was exceedingly expensive, and shipping times were unreliable. At these centers, textbooks were an overall hindrance to teaching and learning.

Our scholarly communication librarian became an OER proponent through his experiences providing copyright consultations to faculty and staff. Because these consultations regularly forced him to confront the restrictiveness of the “All Rights Reserved” copyright regime, he became enamored with the power of open licensing to promote equitable access to information and provide the requisite reuse rights for myriad forms of scholarly and pedagogical innovation. And our instruction librarian wanted to support a wider variety of sources for course materials, providing diverse viewpoints and influencing critical thought—foundational elements of information literacy.

While we approached the search for financially viable and sustainable options from different perspectives, it became clear that there was one common solution: open educational resources.

One additional element made our OER team special and allowed us to jumpstart our initiative: we were unofficial. This does not mean we were unauthorized or unsanctioned; on the contrary, department heads and senior leadership fully supported our endeavor. Yet we were not a faculty committee, or a taskforce, or directed by a library-wide strategic initiative. Without the defining characteristics of a long-standing group, we were able to make decisions on the fly, implement projects on our own timelines, attempt cross-campus partnerships, and delve into our ideas as our framework continued to materialize.

Establishing Our Philosophy and Goals

As soon as our team came together, we began developing a strong and focused philosophy for our OER initiative. This is a crucial step in the formation of an open educational program at any institution, as its sets the direction for the team’s efforts and creates a common vision for success. We based our ideology on what we really cared about and why this initiative mattered to us, individually and for our organization. Primarily, we wanted to save students money, and we were disappointed and frustrated by the current traditional textbook model as publishers continued to drive up the price of course materials, increasing profits at the expense of teaching and learning. We also saw that exciting and effective models were being used at institutions across the country (Young, 2017), and wanted to implement these models on our own campus. Our colleagues at other institutions had been involved in OER programs for years, trailblazing the path and creating a model for local efforts.

Our goals for the initiative were broad and wide-ranging, from promoting the role of the library in pedagogy to developing a community of practice on campus.

Our goals for the initiative were broad and wide-ranging, from promoting the role of the library in pedagogy to developing a community of practice on campus. Our group saw the open movement as an opportunity to further promote and expand the role of the libraries as a student and faculty partner in the classroom and around campus. While following in the footsteps of OER leaders is advantageous and efficient, it is also crucial to develop an OER philosophy that fits your institution, your team, and your community. At FSU, we wanted to create a pedagogically-focused community of practice on our campus and center it on the work, resources, and services of the libraries. Different library units were already engaged in supporting pedagogy, from curriculum-mapped information literacy instruction to deep partnerships with faculty engaged in digital humanities. After one OER team member attended the Digital Pedagogy Lab Institute, for instance, she actively sought to expand the libraries’ place in providing critical and thoughtful support to instructors teaching with technology. In many ways, our current ambitions and energy precisely aligned with the OER and open pedagogy movements.

The Slow-Drip Approach

Once our philosophy and goals were in place it was time for us to begin testing the waters around campus and developing plans, programs, and resources for this community of practice. We adopted what we call a “slow-drip approach.” Rather than implementing broad, campus-wide changes or policies, we started small and searched for natural partners on campus, relying on our library colleagues and on existing cross-campus partnerships.

We use a subject librarian model in the Research and Learning Services department, so we had librarians embedded in various capacities throughout the academic departments. Because these librarians are familiar with the research, faculty, courses, and teaching within these departments, we began our outreach efforts through them, with the goal of dispersing information about OER opportunities to interested faculty and beginning the conversation about open and affordable alternatives to traditional course materials. We also have a number of functional specialists who collaborate with offices, centers, and staff around the university. These library colleagues connected us with additional campus contacts such as our office of Distance Learning and our School of Library and Information Science.

As we began engaging in regular meetings, troubleshooting hurdles, and conceptualizing the use of OERs on our campus, the community of practice we were trying to create materialized organically. New partners and opportunities emerged. The diverse perspectives provided by these partnerships allowed for better problem solving and ideating. And finally, we were able to target the audience most affected by the high-cost traditional textbook model: our students.

Following the Leaders

Launching an OER initiative has never been easier. Leaders in the field have shared a wealth of high-impact strategies and best practices. Researchers have also generated a wealth of data on textbook affordability concerns, student and faculty perceptions of OERs, and the impact of OERs on student learning outcomes, to name just a few of the main research areas (Hilton et al, 2016). By leaning on these valuable resources, we were able to get our program started in a short amount of time. Specifically, we consulted experts in the field, reports on textbook affordability concerns, and a variety of other scholarly and popular resources documenting case studies and best practices.

Along with educating ourselves about OER and textbook affordability generally, our main objectives in conducting an environmental scan were to gather ideas for successful initiatives that we could bring to our campus and to identify relevant resources for planning and executing these initiatives. We identified two proven, complementary strategies for bootstrapping our OER initiative:

- Launching an alternative textbook grant program to incentivize adoption of open and affordable alternatives to commercial course materials

- Facilitating a #textbookbroke tabling event to engage with our students and gather feedback on the impact of textbook affordability concerns at our institution

Because these initiatives had a proven record of accomplishment at other institutions, it was relatively easy for us to convince our senior libraries administration to support them. It was also relatively easy to find case studies, reports, and other resources to expedite the implementation of each initiative. We used the FLVC 2016 Student Textbook and Course Materials Survey (2016) to help establish the need for an OER initiative at our institution, and found many examples of OER mini-grant programs on which we could model our own. The process of identifying these programs has only become easier since we conducted our environmental scan, particularly since the launch of SPARC’s Connect OER platform (2017a), a directory of OER programs and activities at campuses across North America. We also benefited immensely from the BCcampus OER Student Toolkit (Munro, Omassi, & Yanno, 2016), which provides detailed information on how to organize a #textbookbroke campaign.

While planning our initiatives, we were also careful to engage with our subject librarian colleagues, to keep them apprised of our progress and ensure that they could contribute ideas. Although many of them have not been directly involved, we knew it was important to get their buy-in to ensure the program’s long-term sustainability and scalability.

Engaging with our Instructors: Alternative Textbook Grants

We modeled our Alternative Textbook Grants (ATG) program on similar OER mini-grant programs launched across the U.S. in recent years. Although implementation may vary, these programs share a common purpose: providing educators with incentives to adopt, adapt, or create OERs for their courses. In conjunction with these programs, many state governments have passed legislation in recent years to provide central funding for the development of OER incentive programs (SPARC, 2017b).

When we started planning our mini-grant program, there were no established mini-grant programs at other public universities and colleges in Florida that we could use as comparators, and no central state funding available for OER initiatives. Our first task was thus to find a source of funding. We accomplished this by appealing to our libraries’ senior leadership—specifically, our Associate Dean for Collection Development, who had allocated funds from our collections budget for open access initiatives in the past. By presenting evidence of the impact of OER mini-grant programs at institutions across the nation, we were able to convince our leadership to allocate a modest $6,000 for a pilot program. Given the limited size of this allocation, we decided to cap our mini-grants at $1,000 for each proposal to adopt open or library-licensed materials in place of commercial textbooks.

Once we had secured funding, the next step was to decide on the structure of the pilot program, including requirements for applicants and grant recipients, an application evaluation rubric, a memorandum of understanding for successful applicants, and a structured program of workshops and consultations to support our initial cohort of instructors in implementing their alternative textbooks. We benefited immensely from colleagues at other institutions who had launched similar initiatives in the past and shared information about their own programs. For more details on the structure of our program, readers are encouraged to consult FSU Libraries’ Alternative Textbook Grants website.

After seeking input on and approval for our proposed structure from senior leadership and colleagues, our next major task was to get the word out. This was no small undertaking, especially given the size of our university and the fact that we were launching our grant program late in the term. By the time we had finalized the program structure and created a webpage and online application form, we were midway through the Fall 2016 semester and only four months from the application deadline. This tight timeline led us to pursue an outreach strategy that focused heavily on campus-wide communication channels, as opposed to targeted outreach to individual instructors. More specifically, our communication plan included the following tactics:

- Email template and flyer distributed by subject librarians to their liaisons at academic departments

- Email to all faculty distributed by the VP for Faculty Development

- Promotion on social media (Facebook and Twitter)

- Promotion at library events for faculty and grad students

Despite the short timeline, we received seven proposals by the application deadline, and were able to fund six of them. The successful grantees were a diverse group of instructors from different disciplines and at different stages of their academic careers.

Following our selection of grantees, we sent each one a memorandum of understanding outlining the scope of the project, roles and responsibilities, and projected timelines for project completion. We also offered two workshops attended by all of the grantees—one on OERs and Open Textbooks, and another on Open Pedagogy. Finally, we scheduled individual consultations to discuss the projects in more detail and identify the kind and extent of support each instructor would require from the Libraries.

We determined that further support was required for three of the six instructors, and scheduled regular follow-up consultations over the summer of 2016 to discuss material selection, copyright and licensing, instructional design, and learning management system integration. These consultations were an excellent opportunity for us to provide personalized assistance and begin to forge meaningful relationships with the instructors. At the same time, however, they presented scalability concerns, as we quickly realized that we would not be able to sustain the same volume of consultations for a larger cohort of instructors. We are planning to move to a rotating consultation schedule for our next round of grants, giving each grantee the opportunity to meet once with each member of our team to discuss the topics above, rather than providing a recurring series of consultations with the entire team. If additional meetings with a particular team member are required, those can be arranged as well.

With respect to the first-year impact of our program, we estimate that the six instructors who participated will collectively save our students up to $56,000 in textbook costs by the spring of 2018. This figure is based on the estimated annual headcount enrollment for the courses in question and the cost of purchasing new copies of the commercial textbooks previously assigned in those courses. This represents a return on investment (in terms of student savings) of almost 10/1 after one year, with strong potential for equal or greater savings in future years, provided that the instructors continue to use the alternatives identified. Three grantees adopted open textbooks for their courses, and three adopted a combination of library-licensed resources and free online resources, so all of the adopted course materials are available to students at no cost. At the time of writing, four of the six grantees are teaching with their alternative textbooks for the first time, so we have yet to evaluate grantee or student perceptions of the adopted materials or the grant program itself. That said, anecdotal feedback from the grantees suggests that perceptions are positive on both counts.

Our program also enabled us to make meaningful progress toward our two other goals: engaging with our instructors and building a campus community of practice around OERs.

Our program also enabled us to make meaningful progress toward our two other goals: engaging with our instructors and building a campus community of practice around OERs. Our efforts to promote the program, for instance, have led us to engage with faculty at a range of library events and faculty meetings. During one meeting, we met an instructor who had already adopted an OpenStax textbook for his section of General Chemistry I, and who later advocated successfully to extend the adoption across all sections of the course. Since this course has one of the highest enrollments at FSU, adoption of this one open textbook could save our students more than $500,000 by the summer of 2018.

In addition, each of the instructors in the pilot program has since promoted the program to colleagues, with one publishing a blog post in which she encouraged “colleagues and anyone interested to tap into this brilliant, talented, fun and eager-to-assist library team” (Dwyer Lee, 2017). As a result, our team has observed increased awareness of our grant program among both instructors and administrative units on campus. Although evidence of a burgeoning community of practice is currently anecdotal, we plan to test this hypothesis over the coming year through a systematic assessment of instructor perceptions and practices with respect to OERs.

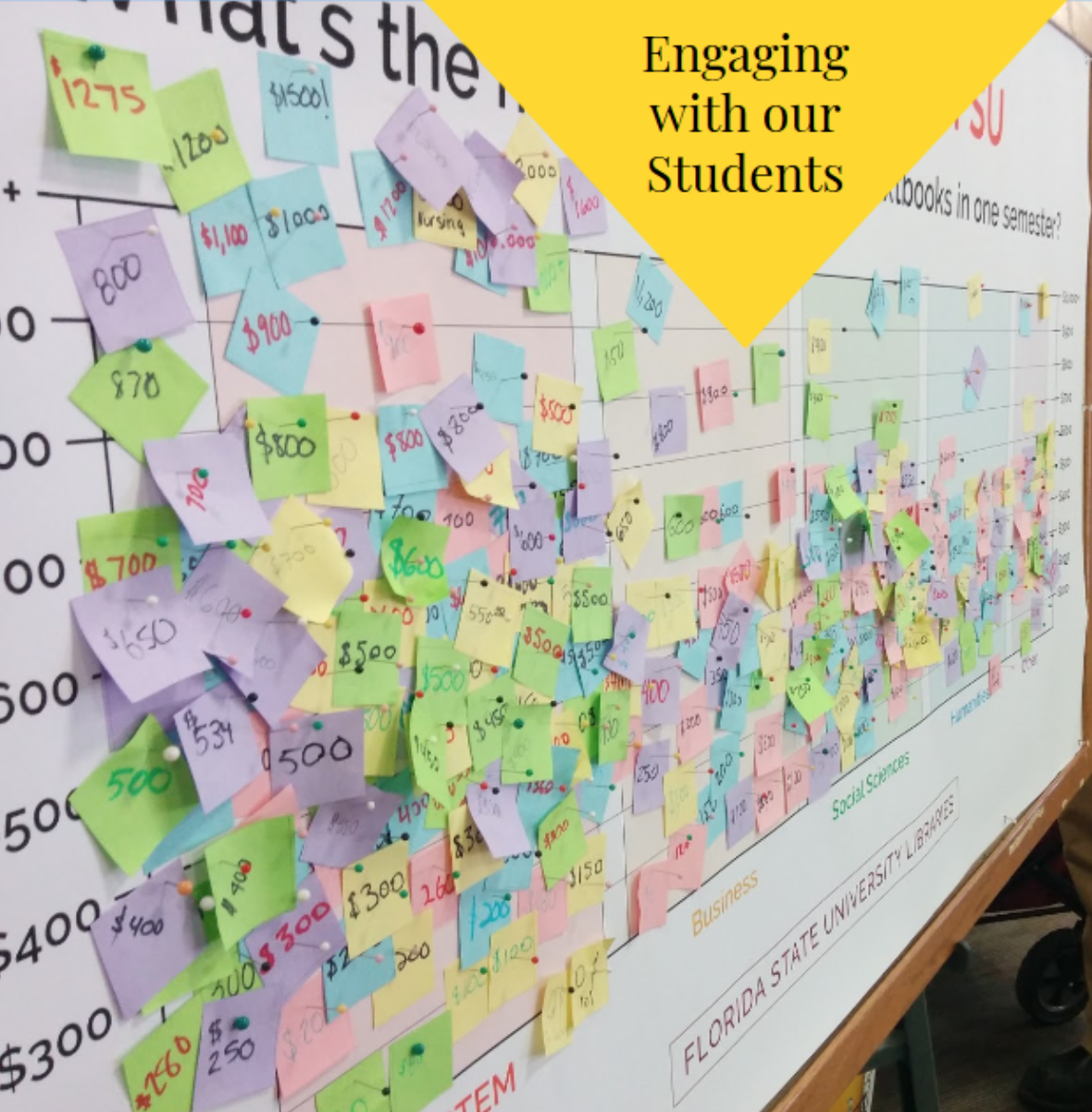

Engaging with our Students: #Textbookbroke FSU

Inspired by the programs at the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University, and by our desire to follow current leaders and trends in the OER arena, we implemented a #textbookbroke initiative on our campus. We developed tabling events and created surveys to determine our student’s thoughts about the cost of textbooks, hoping to gain more insight into how much they were spending on textbooks and how we could alleviate the financial strain. We held these events in multiple locations, including the main library on campus, the science library, and a popular walkway that students cross throughout the day. We gained IRB approval to use the survey, which consisted of the following questions:

- Are you a student/alumnus at FSU?

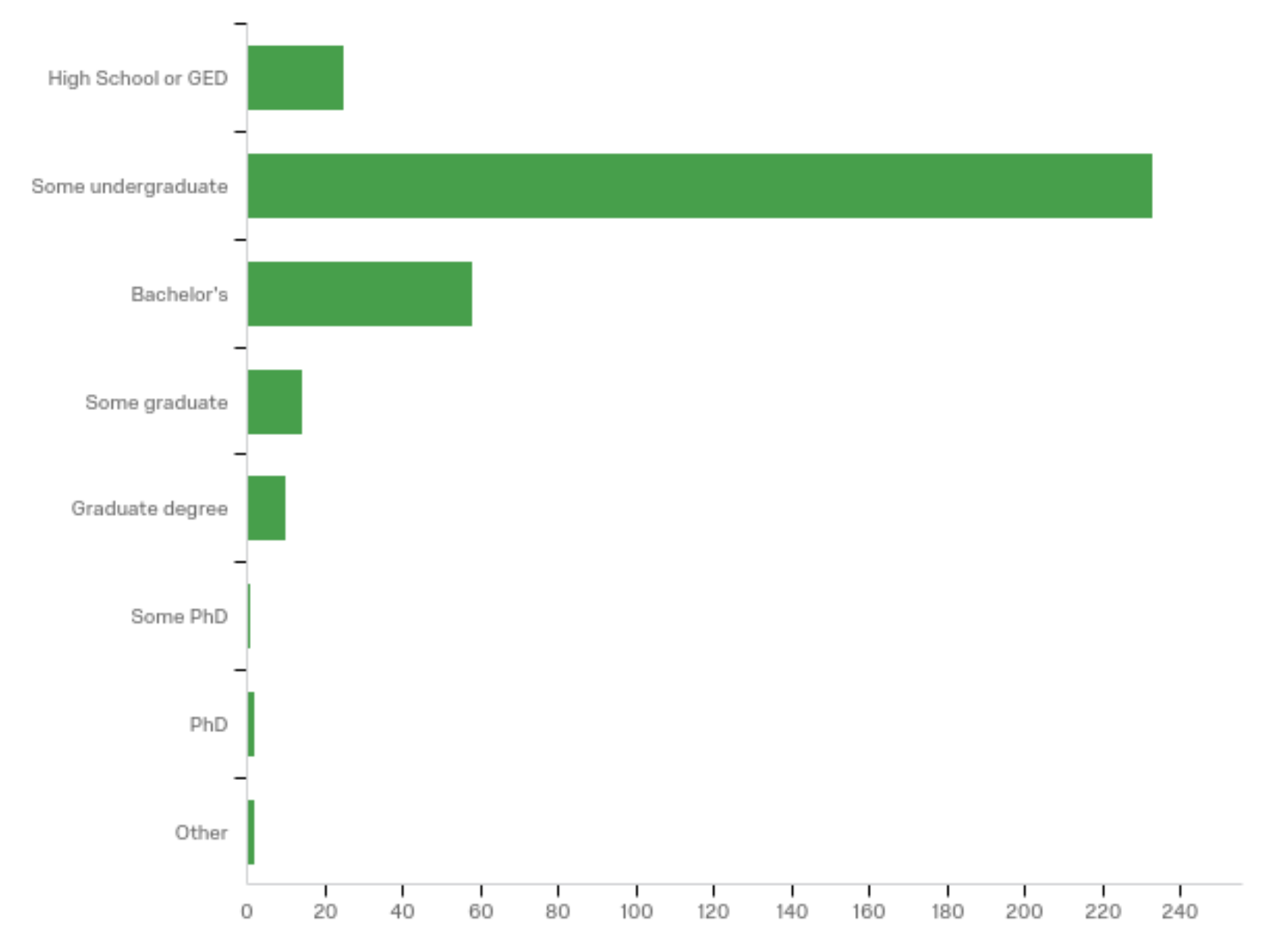

- What is your highest level of education?

- Estimate how much you spent on textbooks last semester

- Would you use an online textbook if it was free?

- Would a $30 print textbook help reduce any financial strain?

- Have you ever not purchased a required textbook due to the cost?

- If so, what college/department was the textbook for?

- Have you ever decided not to take a course due to the cost of the textbook?

- If so, what college/department was the textbook for?

The surveys were located on Qualtrics and we used iPads to present the questions. We often asked the students the questions ourselves and marked the answers on Qualtrics; this increased the speed of taking the survey and encouraged more conversation from the students, who often elaborated beyond the close-ended responses. We received ample feedback at all of our events (n=346), but the two tables inside the libraries received the largest number of responses. Although the outdoor event had significantly more foot traffic, the popularity of the libraries’ events were greater due to an interactive board which allowed students to use a sticky note to write down the largest amount of money they spent on textbooks in one semester. Students placed this note on a large chart divided into five columns—STEM, business, social sciences, humanities, and other—with rows that showed the amount of money spent, ranging from $0 to $1,000+ (Table 1).

This interaction promoted conversation between the librarians and students, providing a insight into student’s thoughts on textbook affordability.

Of the 346 survey participants, 343 were current students or alumni of the university, and the majority (n=233) had taken some undergraduate courses (Table 2). Students had spent an average of $360 on textbooks the previous semester, with a range from $0 to $2,000. Respondents with the highest amount of spending reported biology, chemistry, and nursing as the majors with the most expensive textbooks in one semester.

To determine how students perceived the benefits of using OER resources from OpenStax, we asked “Would you use an online textbook if it was free?” and “Would a $30 print textbook help reduce any financial strain?” Results showed that 93.37% of participants would use an online textbook if it was free, and 97.40% said that a $30 print textbook would reduce financial strain. These data supported our suggestion that the university apply for the OpenStax Institutional Partnership Program.

Our final inquiries asked if students were not purchasing required textbooks for their classes, or if they were avoiding classes because of the textbook’s cost. The survey revealed that only 11% of respondents have decided not to take a course because of textbook costs, but that 72% have decided not to purchase a required textbook due to cost. This number exceeds the 66.6% of students reporting, in the 2016 Florida Virtual Campus survey (FLVC, 2016), that they did not purchase a required textbook.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

As might be expected in the launch of any new initiative at a large research institution, we encountered a number of challenges, the main one being a lack of campus-wide participation. As mentioned above, there was no OER work underway when we launched our initiative, either in our libraries or among key campus partners such as our campus bookstore, the Office of Distance Learning, or the Student Government Association. Although we made every effort to involve these partners, sending emails and setting up meetings to explain our goals and invite collaboration, we were not immediately successful. Because we launched our initiative late in the Fall 2016 semester, many partners had already established their priorities for the academic year and had limited capacity to take on additional work, even when they were interested in collaborating. While this was somewhat disappointing, it also gave us time to focus on our two initiatives to engage instructors and students, both of which were very successful. The lack of campus-wide participation did, however, affect our application to participate in the OpenStax Institutional Partnership Program, which, despite support from our Provost, was not successful in 2017.

Other notable challenges resulted from institutional bureaucracy and policies regarding promotion and tenure. Like many large institutions, FSU has largely decentralized the governance of curriculum decisions to academic departments, many of which have curriculum committees that are responsible for textbook adoption decisions. While this decentralized model doubtless has benefits for departments and course instructors, particularly for high-enrollment, general-education courses, it made it difficult for our team to conduct outreach around our Alternative Textbook Grant (ATG) program. In many cases, we found instructors who were interested in using open textbooks in their courses, but who felt that they did not have the authority to adopt a new textbook without the support of a curriculum committee or department chair. Given the small size of our team and the fact that we launched the ATG program late in the Fall 2016 semester, we didn’t have time to reach out to the relevant committees or chairs before the grant application deadline.

With respect to promotion and tenure policies, FSU places a great deal of emphasis on research output and relatively little on performance in teaching. Several faculty members reinforced this institutional belief to our team, and we found additional evidence in FSU’s Promotion and Tenure guidelines (Sampson Jr, J. P., Driscoll, M. P., Foulk, D. F., & Carroll, P. S., 2016), which devote relatively little attention to defining excellence in teaching and far more attention to research. The guidelines even explicitly discourage faculty from authoring textbooks: “given the often considerable amount of time required to write a book, tenure-earning faculty should generally avoid writing a textbook.” Unlike some other institutions, FSU does not have a tenure-track stream based on teaching. In light of these guidelines, many FSU instructors have expressed reservations about participating in the ATG program due to the perception that it would take time away from their research and publishing activities, negatively affecting their chances of receiving tenure or promotion.

Despite these challenges, however, the first year of our OER initiative was very successful, and our team is optimistic about future development. It is common for a new initiative to receive a lack of campus-wide participation, and we have already begun to overcome this challenge by adding new partners. Although institutional bureaucracy and promotion and tenure policies will doubtless continue to pose challenges, they are far from insurmountable. While some instructors may be discouraged from participating, there will always be innovators who are passionate about OERs and eager to participate despite the challenges. As our experience illustrates, it is often enough for a new OER initiative to seek out the instructors and stakeholders who are ready to participate and build from there. It takes time to raise awareness across campus and to change culture, but you can forge meaningful relationships with the innovators in a much shorter period of time, and these relationships can be a powerful first step toward building momentum on a broader scale.

First-Year Impact

The first year of our OER initiative led to considerable impact in the following three areas: student engagement and savings, increased funding and support, and new partners and collaborators. In terms of student engagement and savings, our #textbookbroke tabling events drew a huge response from our students, including 346 survey responses that collectively showed the extent of textbook affordability concerns at our institution as well as strong support for open textbooks and related affordability initiatives. As noted above, we expect the instructors who participated in the first round of our ATG program to save our students $56,000 in textbook costs by the summer of 2018, a return of almost 10/1 on our Libraries’ investment of $6,000 to fund the grants. Furthermore, our team has also been very pleased to see open textbook adoptions occurring outside of our ATG program, notably in FSU’s General Chemistry I course. This action can potentially save students more than $500,000 by the summer of 2018.

The first year of our OER initiative led to considerable impact in the following three areas: student engagement and savings, increased funding and support, and new partners and collaborators.

Following the early success of our #textbookbroke campaign and ATG program, our OER initiative received increased funding and support from several administrators on campus.

The first evidence of this came in the form of a letter of support from our Provost for our application to participate in the OpenStax Institutional Partnership program. In addition, FSU Libraries’ senior leadership team increased the funding allocation for our ATG program to $10,000 for our second round of grants, and FSU’s International Programs directors allocated an additional $5,000 to fund ATG proposals from instructors at extended campuses. Taken together, these funding increases have almost tripled the ATG program’s initial $6,000 allocation, making it possible for us to offer a larger number of grants. The first-year impact of our OER initiative also enabled our team to raise $3,250 toward hosting an OER symposium during Open Education Week 2018, thanks largely to generous contributions from the Deans of FSU’s College of Education and College of Communication and Information.

Finally, our OER initiative has grown to include several new partners and collaborators. Our monthly meetings now include representatives from FSU’s Office of Distance Learning, iSchool faculty, and graduate researchers in the field of educational technology. Our newly launched Center for the Advancement of Teaching has also become an important collaborator, promoting our ATG program and related workshops for faculty through its newsletter and discussion groups. We have also made headway toward a partnership with our SGA, which has yet to participate directly in our OER initiative but has recognized textbook affordability as an important student concern and expressed interest in working with us.

Future Program Development

As our open and affordable textbook initiative continues to grow on campus, our team looks forward to advancing OER adoption on our campus through the following initiatives.

OER assessment

Since we launched our OER initiative without conducting any formal assessment of stakeholders on our campus, gathering data to support and inform our work will be an important priority moving forward. In addition to evaluating our ATG program through instructor and student surveys, we have also undertaken a campus-wide assessment of instructor and student awareness of and readiness for OERs and textbook affordability initiatives. We are also looking at institutional data to compare the cost of required textbooks with high failure and/or withdrawal rates in specific courses, and are assisting our subject librarians in proactive outreach through comparison of the required course materials list and our library-licensed collection. Though different in scope, these projects will provide our team with valuable insights for future program development and outreach strategies.

OER symposium

In collaboration with faculty partners in the College of Education and School of Information, our team conducted a two-day symposium during Open Education Week 2018. This event was fundamental in raising awareness about the benefits of open and affordable textbooks on our campus, and sparked conversations about open options not only with instructors currently engaged or interested in alternatives to traditional textbook models but also with those new to the OER landscape. The symposium included a keynote address by a nationally-known leader in the OER community as well as hands-on workshops for faculty interested in updating curriculum and course design to align with new, affordable materials.

Coordinating on-campus OER professional development events, like this symposium, is a convenient and comfortable way to promote open education on any campus. To help facilitate the planning and promotion of similar events at other institutions, we have created an Open Science Framework project in which we will make all of our planning materials publicly available under a Creative Commons license.

Open Pedagogy discussion group

A major barrier in many open and affordable initiatives in higher education is the workload for instructors switching from traditional materials to OERs—a process that often necessitates strategic rethinking of courses, if not a complete overhaul. A successful OER initiative requires building a culture around OER use and support for a new way of thinking about teaching and learning based on open principles. The benefits of OERs extend beyond student savings: by leveraging the 5R permissions (Wiley, n. d.) that come with openly licensed resources, instructors have the freedom to tailor course materials to their course learning outcomes and increase student engagement by designing open, learner-centered assignments. “The question becomes, then, what is the relationship between these additional capabilities and what we know about effective teaching and learning? How can we extend, revise, and remix our pedagogy based on these additional capabilities?” (Wiley, 2013). Our team looks forward to hosting an open pedagogy discussion group, open to all interested instructors, to tackle these questions, work through challenges, and stay abreast of the latest developments in the field. Apart from helping us find and connect with innovative instructors, these conversations will help to ensure a sustained OER community on campus, with support for scalability.

High-enrollment courses

After the first year of our ATGs we evaluated the impact of the initiative with a goal of improving the next iteration. We quickly decided to implement targeted outreach for high-enrollment courses, and to increase the grant allocation to $3,000 for courses in the top 10% of courses by headcount enrollment. When our general chemistry course adopted an open textbook, we saw increased excitement and support from our libraries and campus administration. The savings for higher enrollment courses are impressive, and big numbers make for noteworthy publicity about a growing program. Additionally, there is an abundance of open and affordable textbook options for general education courses—the highest-enrollment courses on most college campuses—meaning streamlined workflows for instructors and OER advocates when searching for high-quality substitutions. Focusing on high-enrollment courses is a simple and effective strategy for increasing the impact of OER initiatives on any campus.

Expanding internal and external collaboration

We are determined to continue pursuing new partnerships with stakeholders at FSU and across the state of Florida. We have asked our Provost to form a taskforce of senior university administrators to address textbook affordability concerns and make recommendations for mitigating these concerns. If this request is successful, we hope it will expedite our efforts to involve our campus bookstore and relevant Faculty Senate standing committees, in addition to giving the conversation about textbook affordability initiatives greater visibility across campus. Our team is also pursuing opportunities to collaborate with partners beyond our institution, including Florida’s statewide academic library services cooperative, FALSC, as well as librarians and instructional support staff at other public colleges and universities in Florida. These efforts have already resulted in a legislative budget request to support OERs and textbook affordability initiatives, which is currently being considered by the Florida State University System’s Board of Governors, as well as the formation of a FALSC standing committee to coordinate statewide efforts.

Conclusion

The experience of launching an OER initiative at FSU has been extremely rewarding for our team, our partners, and the many stakeholders interested in textbook affordability on campus. Starting with a small group of four librarians in the fall of 2016, our initiative quickly implemented two successful programs to engage students and instructors, and has since grown to include representatives from key campus partners and attracted generous funding contributions from several university administrators. In approximately one year, our initiative has advanced the cause of textbook affordability at FSU not only through the direct impact of the programs we implemented, but also through the groundswell of faculty and student support arising in response.

Our experience suggests that broad campus awareness and support is not required to launch a successful OER initiative; rather, all that is needed is a few committed individuals to start the conversation and seek out innovators ready and willing to advance change on campus. With the wealth of resources shared by pioneering OER advocates across the US and globally, starting an OER initiative has never been easier, and there are a variety of proven strategies to choose from. By sharing our experience, we hope to provide both inspiration and a practical roadmap for colleagues at campuses that are just getting started with OERs, particularly in cases where minimal funding is available to support OER program development.

References

Dwyer Lee, J. (2017, August 23). Jane Dwyer Lee: Creating an alternative social work textbook. Retrieved from http://csw.fsu.edu/article/jane-dwyer-lee-creating-alternative-social-work-textbook

Florida Virtual Campus, Office of Distance Learning & Student Services. (2016). 2016 student textbook and course materials survey. Retrieved from http://www.openaccesstextbooks.org/pdf/2016_Florida_Student_Textbook_Survey.pdf

Hilton, J. (2016). Open educational resources and college textbook choices: a review of research on efficacy and perceptions. Educational Technology Research and Development, 64(4), 573–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9434-9

Munro, D., Omassi, J., & Yano, B. (2016). BCcampus OER student toolkit. British Columbia: BCcampus. Retrieved from https://opentextbc.ca/studenttoolkit

Sampson Jr, J. P., Driscoll, M. P., Foulk, D. F., & Carroll, P. S. (2016, July 27). Successful faculty performance in teaching, research and original creative work, and service. Tallahassee, FL: Florida State University, Office of the Dean of the Faculties.

SPARC. (2017a). Connect OER. Retrieved from https://connect.sparcopen.org/directory/

SPARC. (2017b). OER state policy tracker. Retrieved from https://sparcopen.org/our-work/state-policy-tracking/

Wiley, D. (n. d.). Defining the “open” in open content and open educational resources. Retrieved from http://opencontent.org/definition/

Wiley, D. (2013, October 21). What is open pedagogy? Retrieved from https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2975

Young, L. (2017, August 28). OER: The future of education is open. Educause Review. Retrieved from https://er.educause.edu:443/articles/2017/8/oer-the-future-of-education-is-open

Author Bios:

Devin Soper has served as Scholarly Communications Librarian at FSU Libraries since July 2015, overseeing initiatives related to FSU’s open access institutional repository, open access book and journal publishing, OER advocacy, and copyright education. Prior to his time at FSU, Devin served as Intellectual Property & Copyright Librarian at the University of British Columbia, where he provided copyright and licensing support for instructors and course designers involved in the creation and delivery of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), in addition to collaborating on a number of projects with colleagues at BC Campus, one of the first publicly funded OER advocacy organizations in North America.

Lindsey Wharton, Extended Campus and Distance Services Librarian, is responsible for ensuring equitable access to library services and resources for all distance learning students as well as students and faculty at FSU’s remote instructional sites and international programs. Lindsey serves as the chair of FSU Libraries Web Advisory Group, co-coordinates the virtual reference service, and leads library integrations within the learning management system. Before joining FSU Libraries in April 2014, she served as the Assistant Director of the Florida Keys Community College Library. Lindsey’s research interests include global library services, emerging technologies, open education initiatives, and digital pedagogy.

Jeff Phillips is the Student Success Librarian at Florida State University, where he serves as the chair of the Professional Development, Research, and Travel Committee, chair of the Library Ambassadors, a personal librarian for the Center of Academic Retention and Enhancement, and the subject specialist for the departments of Mathematics, Education, and Film. Additionally, Jeff helps head the undergraduate instruction team where he is responsible for designing and facilitating library courses that teach college freshman about research and citation management.