Students and Affordable Course Content

Kristi Jensen

by Kristi Jensen, University of Minnesota (bio)

Introduction

Throughout this book, colleagues from across higher education—including faculty, librarians, instructional designers, academic technologists, and others—explain the need for more affordable content options, and provide examples of specific processes and programs. After providing an overview of two important and complex issues tied to affordable content efforts—student preference for print materials and the impact of digital versus print materials on student learning and comprehension—this chapter elevates that student voice by sharing feedback from students at the University of Minnesota (UMN) who enrolled in courses that utilized affordable course content.This wealth of information includes blueprints for how to implement an affordable content program, the pros and cons of particular approaches, and descriptions of why this work is important and how it impacts faculty and students.

One voice that is not as pronounced, perhaps, is that of the student. After providing an overview of two important and complex issues tied to affordable content efforts—student preference for print materials and the impact of digital versus print materials on student learning and comprehension—this chapter elevates that student voice by sharing feedback from students at the University of Minnesota (UMN) who enrolled in courses that utilized affordable course content.

Research on Student Preferences Regarding Course Materials

Limitations of Current Surveys

Affordable content efforts often provide students with digital course materials. Our efforts at UMN are no exception; almost all of the faculty we work with utilize digital course materials in one way or another. Students can print many of those materials themselves, but the cost of this option (either the cost of supplies for personal printers or printing charges for University-provided printing) negatively impacts affordability. Since one of our goals is to save students money, we realized early in our work that we needed to develop an understanding of student attitudes and perceptions about digital materials, discover whether or not students choose to print the course materials in order to use them, and determine the impact of these materials on students’ ability to study for and succeed in a course. In the long run, we planned to survey our students, but until that time we had to rely on information we could gather from others.

Surveys addressing student behavior related to purchasing course materials are numerous, but it was more challenging to find information on how students actually use affordable course materials. Popular press and research publications frequently focus on two issues: student preference for print materials and the impact of digital materials on student learning. As we reviewed publications on these topics, we found conflicting information, along with research that failed to demonstrate the complexity of each issue or provide context reflecting real-life student experience.

Major news publications—the New York Times, the Chronicle of Higher Education, and the Huffington Post, for example—frequently run stories that tout student preference for print textbooks. Numerous issues arise, though, when examining these stories and the research behind them. As Mizrach, Salaz, Serap, Kurbanoglu, and Boustany note, there are issues of scale (too few students surveyed), diversity (the students surveyed are primarily from Western countries), and inconsistent research design (which makes it difficult to discern patterns across studies) (2018, p. 2). Other concerns about the limitations of these efforts arise as well.

Many survey questions, for instance, focus on the text format students prefer when purchasing a textbook. For example, Baron asked students, “If the price[s] were identical, would you prefer to read in print or digitally?” (2015), and in 2010 and 2011 the National Association of College Stores asked students, “If the choice were entirely up to you, what would your preferred textbook option be when taking a class?” Responses to these questions have consistently indicated that students prefer print materials, though there has been slow growth over time in the preference for digital materials. What this approach does not take into account, however, is student preference if the digital materials are free or available at a dramatically reduced price—a powerful advantage of the digital environment.

To ascertain student preference in practice (rather than theory), research needs to include more nuanced and complex questions, such as ”Would you prefer a course with free digital course materials or one with print materials that cost x amount?” (A survey could include multiple versions of this question with different values for x, indicating different price points for students to consider.) Or ”If a digital textbook costs 80% less than a new print textbook, which would you prefer?” The digital environment also provides faculty the opportunity to integrate ungraded quiz questions or other interactive learning exercises that provide students with feedback during the reading experience, and survey questions could address these enhancements as well. With such approaches, research on student preference for print or digital course materials could be expanded to account for the complex circumstances in which students find themselves and to provide needed information to faculty and the professionals advising and supporting them in the course material development and selection process.

Additional Student Behaviors and Attitudes Related to Digital Course Materials

The 2015 article “Exploring Students’ E-Textbook Practices in Higher Education” indicates that lower cost and convenience are the top two influential factors related to student e-text purchases. The article also notes that more than half of American college students have used an e-textbook in at least one course. The 2017 ECAR study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology reports that almost 50% of students—compared to 31% in 2011 (Dahlstrom, de Boor, Grunwald, and Vockley, p. 18)— said they wished faculty would use more ebooks or e-textbooks (Brooks and Pomerantz, 2017, p 24). Finally, according to reports from the National Association of College Stores, the purchase of digital materials increased from less than 3% in 2010 (as reported in the New York Times by Foderaro) to 23% in the 2016/2017 academic year. Despite research indicating that students prefer print, it’s clear that they are buying and using more and more digital materials.

Several chapters in this book describe additional student perspectives and experiences with digital course materials. Rush, Lo, Abdous, and Draper (2018) note the “students’ focus on the quality of the teaching rather than the format of the course materials.” Lang, Salem, and Sparrow (2018), discussing the benefits of digital materials reported by the students they surveyed, report that “Overall, students were pleased with the experience, felt it had a positive impact on their learning, and were particularly happy with the reduced cost and first-day access.” And Walker (2018) notes that a faculty member who surveyed students before and after they used an open educational resource (OER) textbook reported that students liked the digital OER as well as the traditional textbook, that the grade distribution was unchanged, and that fewer students dropped the course.

Student attitudes towards and perceptions of print and digital course materials are complex and changing quickly, and need to be thoroughly explored so that affordable content efforts in higher education are rooted in current and accurate information.

Student attitudes towards and perceptions of print and digital course materials are complex and changing quickly, and need to be thoroughly explored so that affordable content efforts in higher education are rooted in current and accurate information. Singer and Alexander adeptly capture this issue when they note that “there are multiple factors influencing reading in print and digital forms…these factors operate in conjunction, and therefore they cannot be examined in isolation” (2017, p. 1033). To provide successful affordable content programs and services, higher education professionals and faculty must develop a more nuanced, big-picture perspective on the print-versus-digital issue, and, whenever possible, obtain direct feedback from students to guide and inform our work.

The Impact of Digital Course Materials on Learning and Comprehension: A Complex Issue

The question of student preference for print versus digital course materials is, then, less straightforward than it might first appear. But the issue’s complexity pales in comparison to that of student learning and comprehension with print versus digital materials. As Mizrach, Salaz, Serap, Kurbanoglu, and Boustany (2018, p.2) point out, “Current knowledge about the suitability and impact of reading formats, whether print or electronic, for different purposes including learning, comprehension and usability is far from complete.” A number of factors make it difficult to reach a conclusion about the impact of digital materials on student learning and comprehension.

Research indicates, for instance, that the length of a text, the discipline, and numerous other variables affect learning and comprehension. And opinions vary widely regarding measures of success when comparing print and digital texts. Some researchers measure short- and long-term retention within a particular group of students, while others compare performance on quizzes and tests among students utilizing different materials. This focus on different measures of learning success may underlie the numerous conflicts in research study results.[1]

Faculty engagement[2] with a digital text (for example, faculty annotations that add insights to the text) can also increase student engagement, which can positively impact student learning. In their systematic review, Ross, et. al. note that “higher education institutions clearly need to train both their staff and students in how to approach digital texts in order to achieve the best learning outcomes” (2017, p. 8).[M]ost comprehension research doesn’t address the fact that current college students have been taught how to study with print textbooks throughout their educational experience, but have not necessarily been trained on studying with digital materials.This point applies not only to faculty engagement with etexts but to an additional issue: most comprehension research doesn’t address the fact that current college students have been taught how to study with print textbooks throughout their educational experience, but have not necessarily been trained on studying with digital materials. As noted in the New Yorker, “Maybe the decline of deep reading isn’t due to reading skill atrophy but to the need to develop a very different sort of skill, that of teaching yourself to focus your attention” (Konnikova, 2014).

Finally, much of the literature on learning in the print versus digital environments focuses on use of the same content presented in print and in a digital format. Such comparisons ignore the enhancements available in the digital environment (feedback via self quizzing, videos and other multimedia, opportunities for discussion with other students via annotation tools, shared note taking, etc.) to teach material in multiple learning modes, break up large amounts of text, and potentially improve the student learning experience. The 2014 ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Technology notes that “Although technology is omnipresent in the lives of students, leveraging technology as a tool to engage students in meaningful ways and to enhance learning is still evolving” (Dahlstrom and Bischel, p. 34).

Affordable content efforts utilizing digital course materials face a complex array of issues that bring both opportunities and challenges to faculty and students and to the professionals who support them. Almost all of the authors and researchers who discuss student preference for print versus digital materials, and who examine the impact of digital materials on student learning, acknowledge that the use of digital materials is increasing and that this format is here to stay. Wading through the conflicting information on these issues is a large task, but necessary to attain the most successful outcomes possible in our higher education environments. Obtaining student feedback is also crucial. As mentioned above, our work with UMN faculty has provided us the opportunity to seek feedback from our own students so as to compare their responses with what is reported in the research literature.

Partnership for Affordable Content Grant Program and Student Surveys

The University of Minnesota Libraries awarded our first round of Partnership for Affordable Content incentive grants in the spring of 2015. These small awards, ranging from $500 to $1,500, provided a mechanism for us to engage with faculty to implement more affordable course content options. Our primary goals were to provide all students with course content from the first day of class, save them money, and give faculty the opportunity to customize content to meet their own teaching needs and the learning needs of their students.

Our primary goals were to provide all students with course content from the first day of class, save them money, and give faculty the opportunity to customize content to meet their own teaching needs and the learning needs of their students.

The Libraries had spent several years developing the expertise, infrastructure, and relationships to support a wide range of potential project types, including faculty-authored open textbooks, customized digital course packs with open and library-licensed content, discounted textbooks based on the all-students-purchase model, and more. This allowed us to work with faculty to find the best ways of meeting their individual teaching and learning goals. The Hanover Research report on Textbook Affordability Options supports this approach: “No singular, best‐practice approach to textbook affordability exists. To have the greatest possible impact, institutions are advised to take a varied approach to textbook affordability” (2013, p. 4.) Offering a wide range of customized options to faculty participants has been key to the program’s success.

As part of the Partnership for Affordable Content grant process, we provided faculty with an optional student survey to learn more about student experience with the affordable content and about study habits related to the digital formats. Our primary goal for the survey was to gather information to inform our service model and identify areas both of success and of potential improvement. The survey was adapted from one developed for our digital course pack project, with questions changed to reflect the broader experiences of students in a Partnership for Affordable Content course. The survey was first executed at the end of the Fall 2015 semester, and continued through the Fall 2017 semester (excluding Summer courses).

The survey link for each semester was shared with faculty to be distributed to students. Faculty participation was voluntary, and not all courses participated every semester. While students were not required to participate, some faculty provided encouragement or incentives with the hopes of reaching maximum participation.

For those courses distributing the survey each semester, the cumulative response rate varied from a low of 16% to a high of 43%. We reached 10 courses in the Fall of both 2015 and 2016, and six courses in the Spring of both 2016 and 2017. The total enrollment for all four semesters was approximately 2,600 students. Eight hundred students responded to the survey, providing a 30% average response rate across all four semesters. Detail on each course is provided in Table 2, below.

| Semester | # of Classes Surveyed | Total # of Students in all Courses | Total # of Survey Respondents | Survey Response Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fall 2015 | 10 | 508 | 163 | 32% |

| Spring 2016 | 6 | 377 | 59 | 16% |

| Fall 2016 | 10 | 894 | 385 | 43% |

| Spring 2017 | 6 | 852 | 193 | 23% |

| Total | 32 | 2631 | 800 | 30% |

Table 1. Number of courses surveyed, student enrollment, survey response count, and percentage

Twenty-one courses are represented in the student survey results, with several surveyed during multiple semesters: six courses were surveyed twice, one was surveyed three times, and one was surveyed four times. A broad array of course subject areas is represented as well (see Table 2). The types of affordable content utilized in each class varied, and included faculty-authored open textbooks, discounted commercial digital textbooks, library-licensed ebooks, book chapters, scholarly and popular articles, and full or partial open textbooks.

| Course Subject Areas | Type of Affordable Content Utilized | % of Respondents across all 4 semesters |

|---|---|---|

| Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics | Faculty-authored open textbook | 6.25% |

| Agricultural Education (2 courses) | Course 1 – Faculty-selected open content

Course 2 – Discounted all-inclusive purchase model |

Course 1 – 6.13%

Course 2 – 1.38% |

| Curriculum and Instruction | Faculty-selected library licensed/Fair Use content | 0.88% |

| English as a Second Language | Open textbook | 1.38% |

| French | Print course pack and some faculty-provided items/Fair Use content | 2.63% |

| Geography | Faculty- and teaching assistant-produced open textbook | 11.63% |

| Hindi-Urdu Language | Faculty-created and faculty-selected web video content | 0.63% |

| Industrial Engineering | Open, library-licensed, and fair use content | 4.5% |

| Journalism | Faculty-authored open textbook | 15.25% |

| Kinesiology | Discounted all-inclusive purchase model | 5.25% |

| Math (2 courses) | Two courses with faculty-created open licensed videos and openly licensed content | Course 1 – 2.00%

Course 2 – 10.00% |

| Nursing | Digital course pack with library-licensed material | 0.63% |

| Post-Secondary Teaching and Learning (Math focus) | Faculty-adapted openly licensed textbook | 3.25% |

| Psychology (2 courses) | Course 1 – Openly licensed content

Course 2 – Faculty-created digital course pack of library-licensed and open web content |

Course 1 – 2.75%

Course 2 – 12.50% |

| Public Health (2 courses) | Faculty-created digital course pack of library-licensed and open web content for both courses | Course 1 – 0.88%

Course 2 – 3.88% |

| Sport Management | Faculty-created digital course pack of library-licensed and open web content | 0.5% |

| Statistics | Library-licensed multi-user ebook and digital course pack with library-licensed content | 7.75% |

Table 2. Subject areas covered, affordable content types used, and percent of total respondents by course/subject area

While the survey data represent students studying a broad array of topics, students in Journalism, Psychology, Geography, and Math account for more than 50% of the respondents. Course data were shared with individual faculty, but for the purpose of this meta analysis the data were combined to provide the broadest possible perspective and feedback.

Student Survey Results

Student Usage of Affordable Course Content

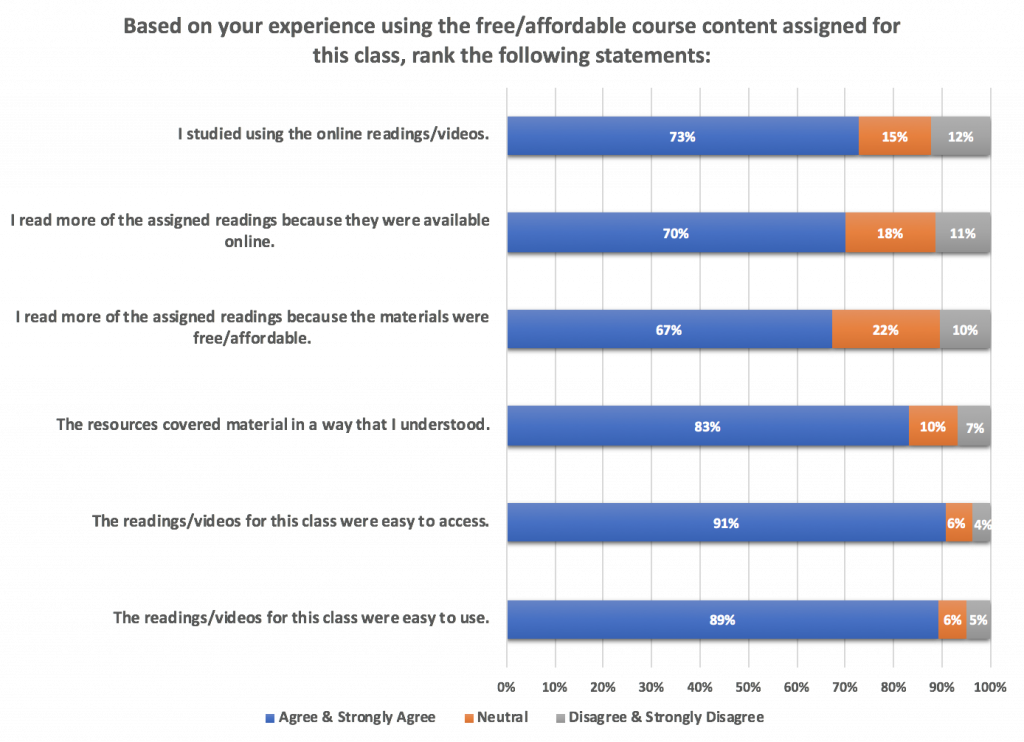

To better understand the students’ experience engaging with the digital course material provided by their instructors, we presented a set of six statements; students indicated their responses on a five-point scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. The six statements in this set included:

- The readings/videos for this class were easy to use.

- The readings/videos for this class were easy to access.

- The resources covered material in a way that I understood.

- I read more of the assigned readings because the materials were free/affordable.

- I read more of the assigned readings because they were available online.

- I studied using the online readings/videos.

Answers provided us with feedback on general navigation and access—an area of concern, given the publications we had read indicating student preference for print. In some cases, course materials were compiled from a broad array of resources (unlike a traditional textbook, which is developed to provide consistency and flow), so we also wanted to make sure students found the materials understandable. Finally, we wanted to understand students’ perception of how they used the material and the impact of the digital and free/affordable material on their reading practices. In general, students responded positively to this set of questions, with the top two categories, Agree and Strongly Agree, accounting for 60–90% of the total responses and the bottom two categories accounting for only 3–12%.

Chart 1. Student responses to questions on ease of use and access, understandability, and the impact of free and digital materials on reading habits

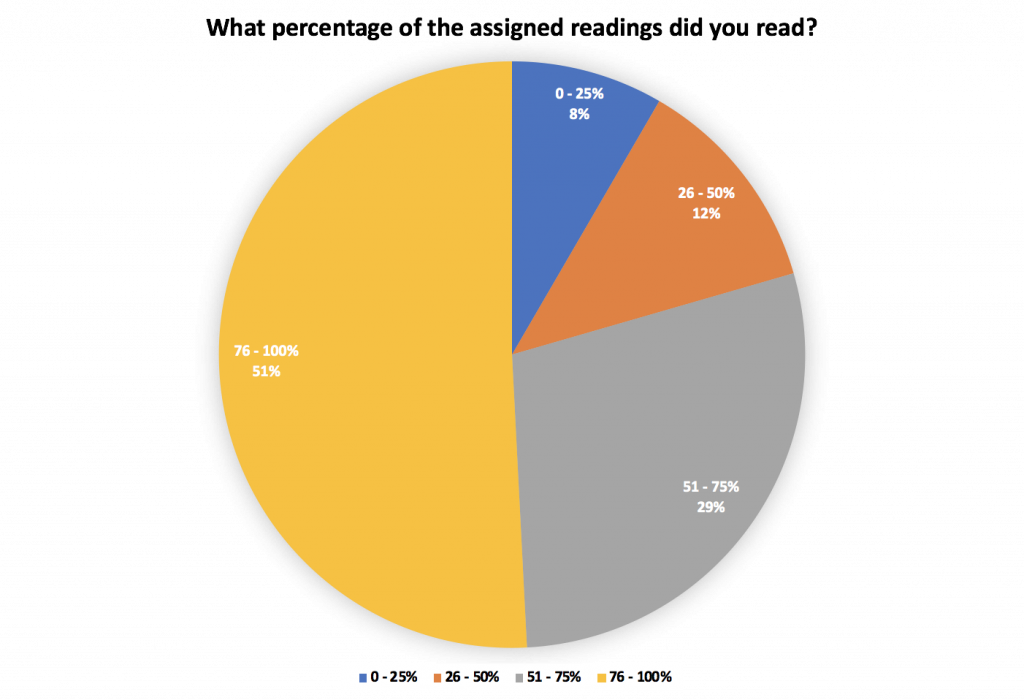

Percentage of Materials Read by Students

Students also reported their perception of the percentage of assigned materials they read during the course. Approximately 80% indicated that they read more than 50% of the material. Throughout this work, faculty have frequently reported concerns about students not reading required course materials. In the article “Students Learn Equally Well From Digital as From Paperbound Texts” (2011), Taylor found that “the key to student comprehension appears not to be the method of text delivery but, rather, getting students to read in the first place.” (p. 278) While we have no data from previous iterations of these courses to compare against, these initial surveys do provide baseline data for future comparisons, especially for courses that continue to evolve and in which faculty apply interactive components meant to engage users in the digital environment.

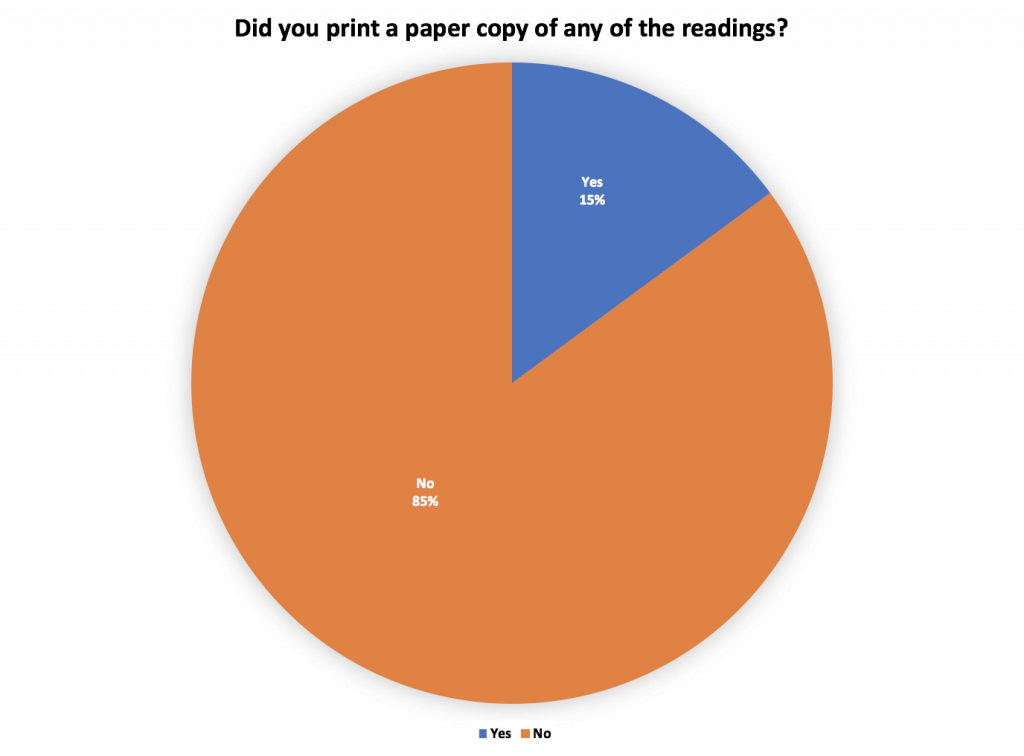

Printing Digital Course Materials

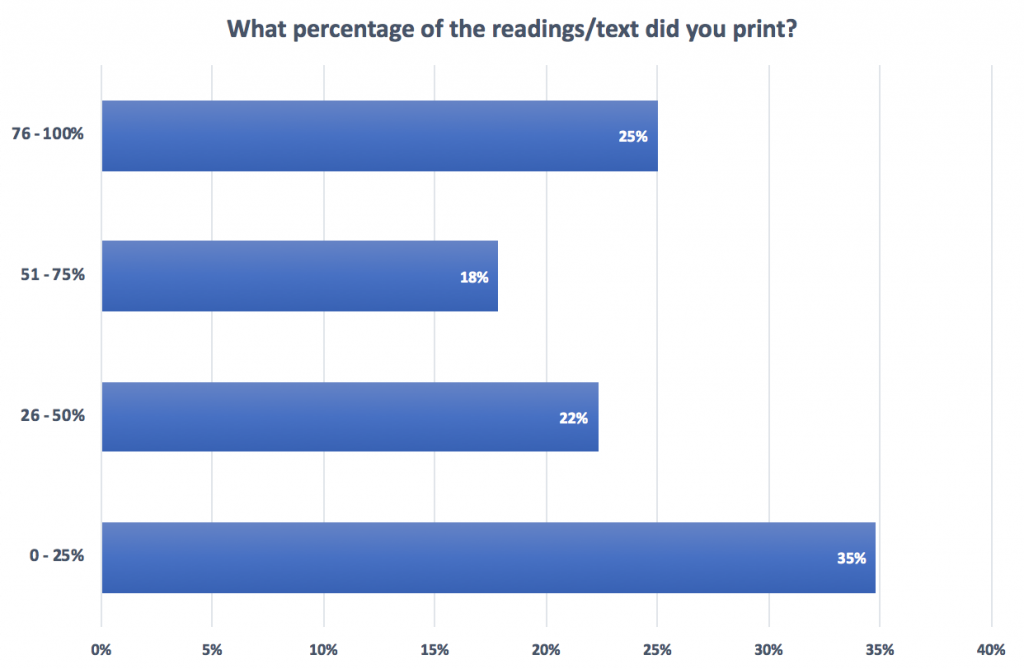

As mentioned above, we were particularly interested to learn if students printed out the course materials in order to use them. With the exception of videos, print options were generally available for all course materials, but just 15% (119) of the survey respondents reported printing any of the materials.[3] Despite research indicating that large percentages of students prefer print to digital materials, these numbers were not reflected by the real-life practice of students in our affordable content courses.

Among those students who reported printing out course materials, a majority printed 50% or less, while 25% (28 students) printed more than 75%. While the number of students printing materials is relatively small, and the percentage printing a majority of the readings is even smaller, there clearly are students who utilize print materials for their learning experience. When considering future surveys, we may add questions to help us determine whether those students needing print materials are receiving adequate support, and what percentage of students are reading online versus via print.

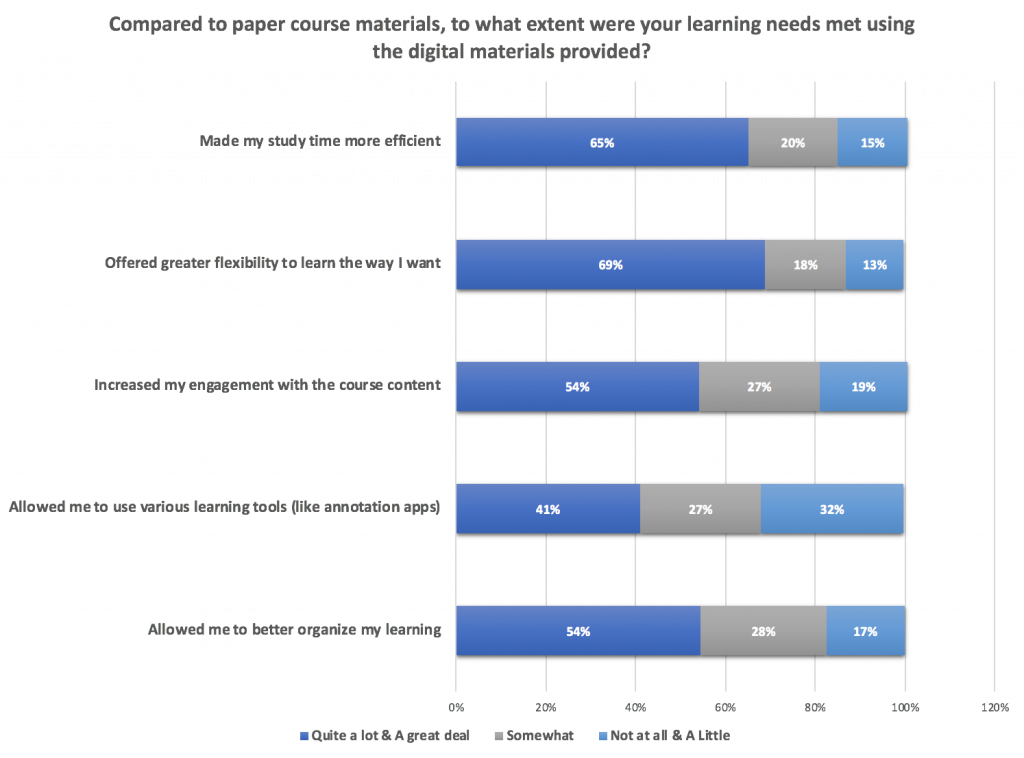

Digital Materials and Student Learning Needs

An additional set of five questions provided insights into the impact of digital course materials on student learning, addressing learning efficiency, flexibility, and organization; engagement with the course materials; and use of tools (like annotation applications). Once again, student response was generally very positive, with the top two categories, “Quite a lot” and “A great deal,” accounting for 41–69% of responses across the question set. The bottom two categories accounted for 18–28% of responses. More than 70% of students indicated that the affordable content increased their engagement with the course materials and allowed them to better organize their learning—boding well for student success in these courses.

Further exploration of how students use these learning tools should address the potential need for additional training to enhance student learning experiences, aspects of digital materials that lead to student perception of increased engagement, and content elements that provide for better organization of learning. We could also gather information on the impact of these variables on student comprehension, looking, for example, at whether the use of annotation tools or ungraded quizzes improves student perception of their comprehension of the course materials.

Chart 5. Student responses to questions on how their learning needs were met by the digital materials

Chart 5. Student responses to questions on how their learning needs were met by the digital materials

What Worked Well and What Challenges Did You Face?

The student voice comes through clearly in responses to a number of open-ended questions included in the survey, including two of the most informative:

- What worked well for you when using the digital course readings/videos?

- What challenges did you face using the digital course readings/videos?

Answers to these questions were not required; we received 480 responses to the first question, and 474 to the second. Due to the representation of multiple themes in some responses, responses were coded to determine common themes. There were 675 coded items for the first question and 512 for the second.

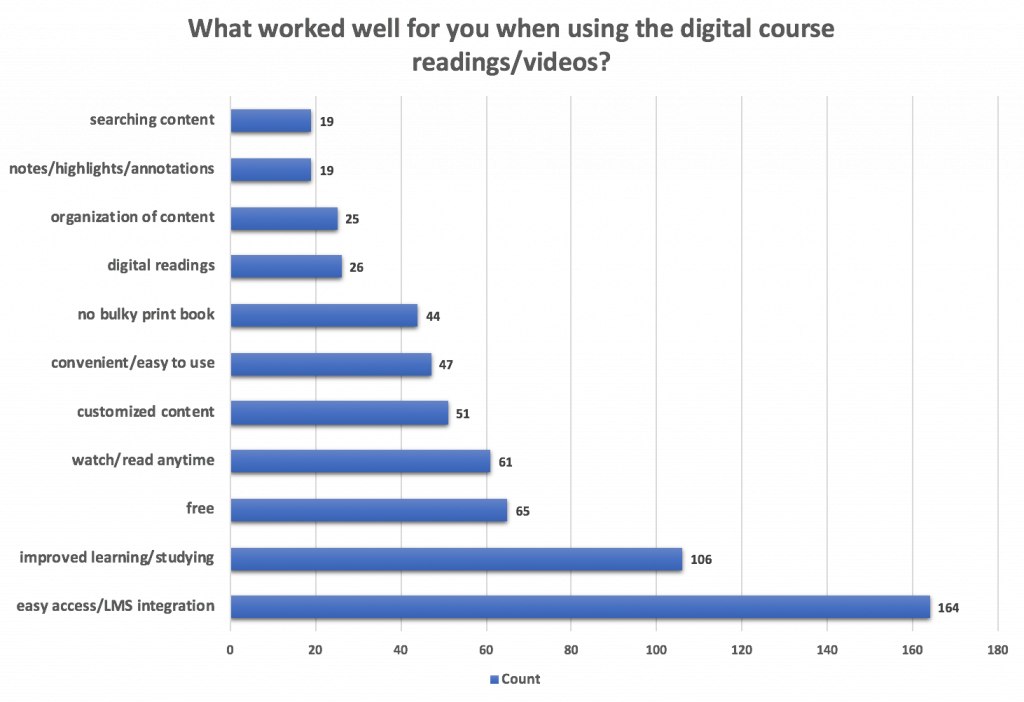

What Worked Well?

Student responses to the question “What worked well for you when using the digital course readings/videos?” focused on the numerous benefits of digital materials, such as ease of access (including integration with the LMS), the ability to read the materials any time, and the lack of bulky print textbooks. Students also reported improved learning and studying, and noted that the content was free and had been customized to enhance their learning experience. Our data (in the chart below) aligned with Weisberg’s findings in “Student Attitudes and Behaviors Towards Digital Textbooks,” where students cited the following factors for increasing the desirability of eTextbooks over paper textbooks:

- “provide greater convenience and portability

- are lower cost; less expensive than paper textbook

- offer a valuable ability to conduct search of the content

- are appropriate media and desired by the ‘‘Y’’ generation.” (2011, p. 194)

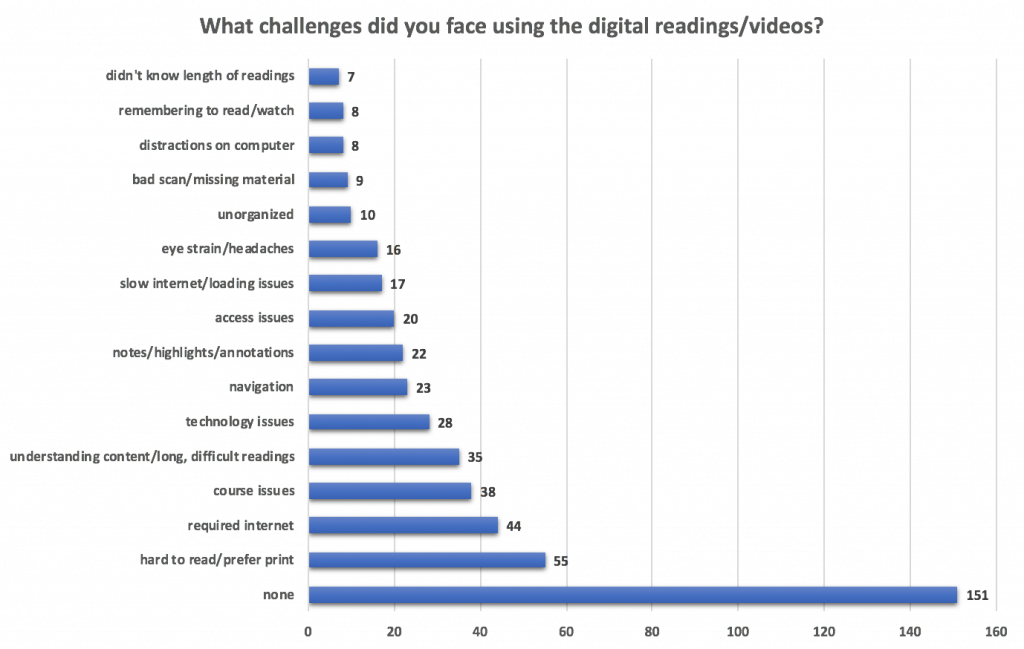

What Challenges Did You Face?

For the question about the challenges of using the digital course materials, it is both interesting and reassuring to note that the largest response—at 30% (151 responses)—was “none.” The next largest response, at 11% (55 responses), indicated a difficulty reading digital materials (students did not like reading on a computer) and a preference for print materials. Even if this response is combined with the eye strain/headaches response, only 14% of students reported concerns about using digital material—a far lower rate than that presented in the research studies cited above. Another 14% of the reported challenges related to course issues or criticism of the length/type of readings, with a majority of these comments valuable to faculty but not related to the affordable content aspect of the courses. Approximately 22% of the challenges reported by students were related to technology, navigation, note-taking, access, and internet speed. All of these tech-related issues reflect student expectation of “effective, frequent, and seamless use of technology” (Dahlstrom, de Boor, Grunwald, and Vockley, p. 22), and when the specifics are reviewed provide insights into how we can better support the student experience. For example, although internet is required to first access materials, many can then be downloaded for offline reading. Additional information could be distributed to students to help them understand how to overcome this particular issue.

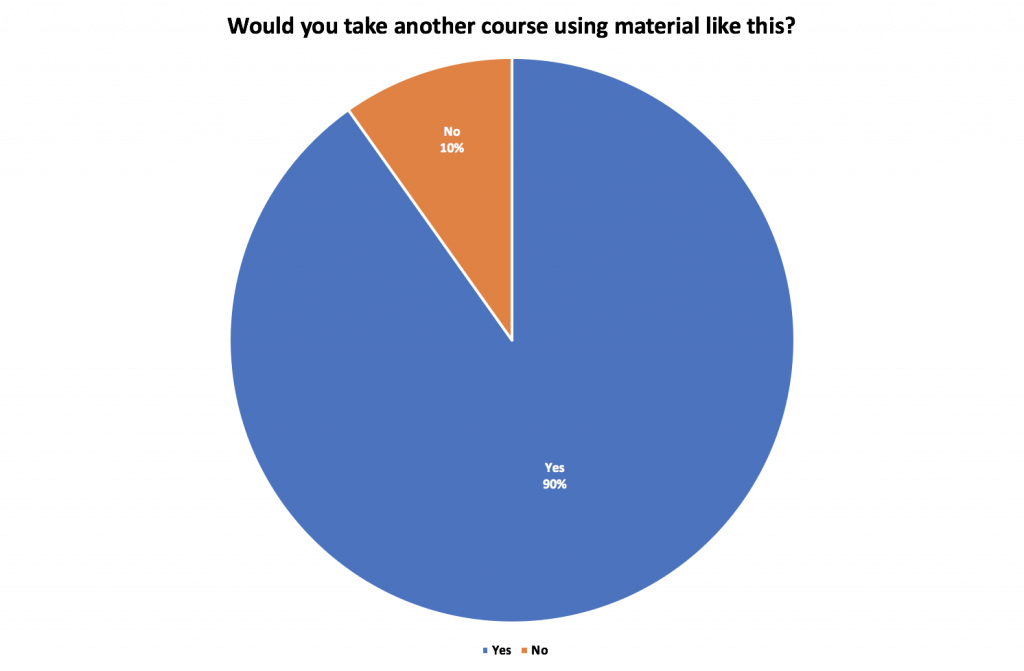

Would Students Do It Again?

One final survey question addressed whether students would take another course using affordable course content. Student response was overwhelmingly positive, with 90% reporting that they would.

Throughout the survey data, and especially in the responses to this last question, we saw that the use of digital materials did not negatively impact the learning experience of a majority of the students. Indeed, in many instances, students indicated that the free or affordable nature of the content improved their learning experience.

Conclusions/Summary

Working with faculty to offer affordable course content to students solves a number of problems: all students have materials from the first day of class, creating a more equitable learning experience; faculty can customize the content to meet their learning goals; and the addition of interactive components creates greater engagement and enhances the learning experience. Headlines frequently tout student preference for print materials and the potential for decreased levels of comprehension with digital materials, but the research literature has produced conflicting results on both of these topics. We have thus relied on frequent surveys of our students in affordable content courses to provide insights into their behaviors and experiences. Their feedback has been critical to the evaluation of our program, and has helped us determine how we can best support students and faculty. Our results show the many benefits students have experienced in these courses, identify potential areas of improvement for our services and programs, and highlight areas where we might benefit from gathering additional information.

The course content environment continues to evolve, but it is clear that the use of digital course materials is growing and that they are here to stay. As Singer and Alexander note, “It is fair to say that reading digitally is part and parcel of living and learning in the 21st century” (2017, p.p. 1034–1035). Academic institutions have a responsibility to support faculty and students navigating this environment, and to ensure the best possible teaching and learning experiences. Understanding the student experience is one key factor in developing the needed support systems. While conflicting evidence related to print and digital materials exists in the research, the results of our student surveys indicate that a majority of students have a positive experience and would take another course using digital materials. Given this positive response, we expect our program and services to grow and change along with the developing affordable course content environment.

References

Anderson, K. (2010, November 3). Do students really prefer print books to e-books? [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2010/11/03/students-prefer-print-books-to-e-books-not-because-of-the-medium/

Baron, N.S. (2015, February 4). Reading on screen vs. on paper. [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://blog.oup.com/2015/02/reading-on-screen-versus-paper/

Brooks, D.C. & Pomerantz, J. (2017). ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2017. Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research.

Dahlstrom, E., de Boor, T., Grunwald, P. & Vockley, M. (2011). The ECAR National Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology. Boulder, CO:EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research.

Dahlstrom, E. & Bichsel, J. (2014). ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2014. Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research.

Dennis, A.R., Abaci, S., Morrone, A.S., Plaskoff, J., & McNamara, K.O. (2016). Effects of e-textbook instructor annotations on learner performance. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 28, 221-235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-016-9109-x.

deNoyelles, A., Raible, J. & Seilhamer, R. (2015) Exploring Students’ E-Textbook Practices in Higher Education. EDUCAUSE Review. Retrieved from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2015/7/exploring-students-etextbook-practices-in-higher-education

Foderaro, L.W. (2010, October 19). In a Digital Age, Students Still Cling to Paper Textbooks. New York Times, p. A21. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/20/nyregion/20textbooks.html

Hanover Research. (2013). Approaches to Textbook Affordability. Retrieved from http://www.asa.mnscu.edu/commission/Documents/Meeting%20Materials/September%202013%20-%202/Approaches_to_TextbookAffordability.pdf and http://slulibrary.saintleo.edu/ld.php?content_id=15124451

Konnikova, M. (2014, July 16). Being a Better Online Reader. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/science/maria-konnikova/being-a-better-online-reader

Lang, J. Salem, J. & Sparrow, J. (2018). The open and affordable course material initiative at Penn State. In K.L. Jensen & S. Nackerud (Eds.), The Evolution of Affordable Content in Higher Education. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from https://open.lib.umn.edu/affordablecontent/chapter/the-open-and-affordable-course-material-initiative-at-penn-state/

Ross,B. Pechenkina,E. Aeshmliman,C. & Chase, A-M. (2017). Print versus digital texts: Understanding the experimental research and challenging the dichotomies. Research in Learning Technology, 25. http://dx.doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v25.1976

Mizrachi D., Salaz A.M., Kurbanoglu S., & Boustany J. (2018). Academic reading format preferences and behaviors among university students worldwide: A comparative survey analysis. PLoS ONE 13(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197444

National Association of College Stores OnCampus Research Division. (2010) Electronic Book and e-Reader Device Report. Retrieved from http://www.nacs.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=blmPMgdQ_LA%3D%26tabid=2471%26mid=3210.

National Association of College Stores OnCampus Research Division. (2011) UPDATE: Electronic Book and eReader Device Report. Retrieved from http://www.nacs.org/LinkClick.aspx%3Ffileticket%3DuIf2NoXApKQ%253D%26tabid%3D2471%26mid%3D3210.

National Association of College Stores. (2017). Highlights from Student Watch Attitudes & Behaviors toward Course Materials 2016-17 Report. Retrieved from http://www.nacs.org/research/studentwatchfindings.aspx

Rush, Lucinda, Lo, Leo, Abdous, M’hammed and Deri Draper. (2018). All hands on deck: How one university pooled resources to educate and advocate for open educational resources and afffordable course content. In K.L. Jensen & S. Nackerud (Eds.), The Evolution of Affordable Content in Higher Education. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from https://open.lib.umn.edu/affordablecontent/chapter/all-hands-on-deck-how-one-university-pooled-resources-to-educate-and-advocate-for-affordable-course-content/

Singer, L.M. & Alexander, P. A. . (2017). Reading on paper and digitally: What the past decades of empirical research reveal. Review of Educational Research, 87, 1007-1041.

Taylor, A.K. (2011) Students learn equally well from digital as from paperbound texts. Teaching of Psychology, 38, 278-281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311421330

Walker, S. (2018). Facilitating Culture Change to Boost Adoption and Creation of Open Educational Resources at the University of North Dakota. In K.L. Jensen & S. Nackerud (Eds.), The Evolution of Affordable Content in Higher Education. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from https://open.lib.umn.edu/affordablecontent/chapter/facilitating-culture-change-to-boost-adoption-and-creation-of-open-educational-resources-at-the-university-of-north-dakota/

Weisberg, M. (2011). Student attitudes and behaviors towards digital textbooks. Publishing Research Quarterly, 27, 188–196.

Author Bio: Kristi Jensen is the Program Development Lead for the eLearning Support Initiative at the University of Minnesota Libraries. She co-manages the Libraries’ Partnership for Affordable Content grant program, is working with campus partners (the Center for Educational Innovation, Academic Technology Support Services, and the Disability Resource Center ) to develop a streamlined and highly coordinated Teaching and Learning support model on campus, and works with partner institutions through the Unizin Teaching and Learning group to further Affordable Course Content efforts at the national level.

- Two systematic reviews on the impact of digital texts on learning (Singer and Alexander (2017) and Ross, Pechenkina, Aeshmliman, and Chase (2017) provide examples of conflicting evidence and results found in the research they review. ↵

- Dennis, Abaci, Morrone, Plaskoff, & McNamara (2016), in “Effects of e-textbook Instructor Annotations on Learner Performance,” examined the impact of instructor engagement with an etext on student learning and found “that the instructional affordances that an interactive e-textbook provides may lead to higher-level learning.” (p. 232). ↵

- Due to an error during the initial survey development, seven students who reported printing materials during the fall of 2015 were not required to answer the second part of the question indicating the percentage of materials printed. ↵